From ‘The History of the Great War'

Edited by Newman Flower for Waverley Book Company

CHAPTER XXXVI

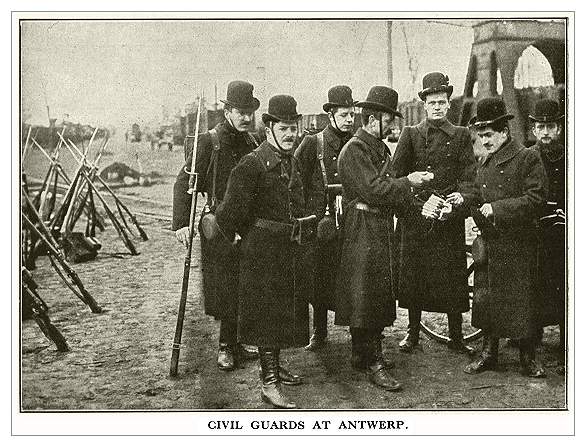

THE DEFENCE AND FALL OF ANTWERP

Magnificent Work of Belgian Army - Retirement to Antwerp - A Belgian Offensive - The Kaiser Tries to Bribe King Albert - Belgium's Answer - German Advance on Antwerp - A Fine Defence - Attack on the Forts - In the City - Arrival of British Marines - Spies in Antwerp - Shelling of the City - Belgian Preparations for Evacuation - The Retirement - The Flight from Antwerp - Entrance of the Germans - Rawlinson's 4th Army Corps

At the very moment when Joffre and French were discussing their great turning move, stirring things were happening in Belgium. After the last stand at Louvain and the fighting round about Malines, all that remained of the Belgian Army retired to Antwerp, where for a time they passed into a species of oblivion, their very existence being almost forgotten in the face of the greater issues at stake elsewhere. It was also known that the gallant Belgian ruler was personally averse to employing them again in extended field operations - at any rate for the present.

They had done magnificently. They had astonished Europe and put up one of the finest fights on record, but their losses had been terribly severe, not only in men, but in officers, and it would take a long time before the gaps could be filled.

A Belgian Offensive

Nevertheless, when it became known that the German general, von Boehn, was on the march southward, a great sortie was made from Antwerp to harass him.

The Belgians retook Alost, reoccupied Malines, and even got as far as Courtenberg and Nosseghem, between Brussels and Louvain, and the result of the heavy fighting was to bring back the bulk of von Boehn's army in hot haste.

Brilliant as the sortie was, it opened the enemy's eyes to the fact that Antwerp was a danger spot for them and arrangements were made for its reduction. Before that took place, however, the German Kaiser, with that singular lack of insight into national character, and that gross bad taste which has marked his actions during the war, attempted to negotiate with King Albert.

Attempt to Bribe King Albert

Through the medium of a well-known Belgian resident, the King was asked to remain quiet inside his defences, and to abstain from any interference with the German lines of communication while they prosecuted their campaign against the Allies in France. In return for such a promise the Kaiser undertook to leave Antwerp unharmed.

The answer to this choice morsel of Teutonic impertinence was prompt and to the point, and the Germans began their operations. A glance at the map shows Antwerp on the "lazy Scheldt", protected by a vast girdle of forts. Behind the outer girdle, and about six miles from the city, the rivers Nethe and Rupel form another line of defence, while outside the city borders, also to the east and south, there are seven more forts, forming a rough segment of a circle, these being known by their numbers. Under the artillery conditions of the time when those outer and inner girdles were constructed, if manned by a determined garrison the city would have been practically impregnable.

In 1914, however, thanks to the heavy ordnance with its tremendous range, they were destined to share the fate of the Liege forts, and the result was almost a foregone conclusion from the start.

The German advance began on the 26th of September and was directed against Termonde, where the enemy made an attempt to cross the Scheldt.

They had massed a strong force with which to cross the repaired bridge which connected Termonde with Grembergen, but a young sub-lieutenant, Raymond Hiernaux, of the 4th Artillery Regiment, ordered his concealed battery to reserve fire until the enemy were on the bridge. Then he gave the word, and the advance party was blown into eternity. A second attempt was made under cover of machine guns hidden among the houses, the attackers wrapping themselves in looted mattresses. Again the Belgian guns swept them away, the mattresses catching fire. Yet a third attempt met with the same result, but the Germans then brought a heavy battery to bear, and the gallant Hiernaux was killed, happily surviving long enough to see the bridge blown up by his men and the enemy foiled.

The names of two villages outside Termonde, Audegem and Lebbekke, will for ever be blazoned in letters of gold on the Belgian standards. At the first place on the 26th and at the other on the 27th, the Germans attacked in very superior force, only to be repulsed and driven back. The fighting was over a front of 10 miles and of the most determined description.

At the same time, other abortive attempts were made, and the net result was an abandoning of all idea of forcing the river for the time.

Attack on the Forts

Instead, they turned their attention on the forts of the outer girdle, after previously shelling Malines on the 27th. At 9.30 on the Sunday they opened upon the Cathedral of St. Rombaut as the people were returning from Mass, the first shell falling in the middle of the worshippers and killing several.

An average of 50 shells an hour fell into the town, the first one at 8 o'clock dropping on the railway station. It was the third time Malines had been bombarded, although it was an open town, but this time the destruction was very thorough; the station, the Home of the Little Sisters of the Poor, the barracks, the National Stamp Manufactory, and many private houses being set on fire, and the Cathedral almost destroyed.

German Heavy Artillery

On Monday, the 28th, the devastators turned their heavy artillery on the two southernmost forts, Waelhem and Wavre Ste. Catherine. The 28 cm. (11.2 in.) howitzers continued firing all day, and proved themselves, as they had done at Liege, to be very terrible weapons. Weighing only 6.3 tons, or, including their carriages and recoil cylinders, 14.8 tons, they had a maximum range of 10,900 yards, and flung a shell weighing 760 lbs.

On Tuesday the magazine of Fort Waelhem exploded, and Wavre Ste. Catherine was knocked to bits, the German attack then turning eastwards and bombarding the Koningschoyckt and Lierre forts.

On Wednesday a serious disaster occurred, for not only was Waelhem completely destroyed, but the waterworks close by were seriously damaged, one shell falling into the centre of a huge reservoir with remarkable effect. Not only were some of the trenches flooded in consequence, but the main water supply of Antwerp was cut off.

On Thursday, October the 1st, an attempt was made to rush the Belgian trenches, but for all its beef and brawn the German infantry was only formidable in enormous masses, and the plucky Belgians drove them back with considerable loss.

It was not until the next day, when the enemy's shrapnel had rendered the trenches untenable, that the Belgians retired behind the river Nethe, about six miles in front of Antwerp, and lined the right bank of the little tidal stream after blowing up the Waelhem bridge.

Closer and closer, in spite of the magnificent defence, the ring of steel was being welded round the doomed city, and already many of the inhabitants had left and were leaving it.

Antwerp is a city with a history, dating back to the seventh century, if not before that. The traveller approaching up the loops and winds of the great waterway sees the beautiful spire of the Cathedral dominating the flat landscape long before there is any vestige of the city in sight. It is a striking landmark which one never forgets, and its carillon of 99 bells lingers long in the memory.

For once the invaders spared an architectural treasure, and although when the actual bombardment began shells were dropping perilously close to it, the Cathedral remained untouched.

It is a fact which accentuates their insensate barbarity in other places, hut it must not be supposed that they had seen the error of their ways. They intended Antwerp to be a permanent German seaport, and wished to preserve its ancient glories intact. To this end the General requested a map on which all the places of antiquarian interest should be marked, promising to spare them as far as possible, and doing so.

A fine city with a happy blending of the ancient and the modern, Antwerp contained many treasures. Its pictures :alone were priceless, and Rubens' "Descent from the Cross," wisely removed to a place of safety, was only one of many. Perhaps the antiquarian gem of Antwerp was the Plantin-Moretus Museum, the perfect house of the perfect old printer, a veritable dream of other days, and this, too, escaped harm.

Everything that ingenuity could suggest and trenching and electrified barbed-wire effect, had been done to protect the approaches to the city, but the defence lacked one all-important factor. There were no guns heavy enough to silence those 28 cm., and even, it was whispered, those 42 cm., which had been brought up from Maubeuge presumably for the bombardment. That either were used for the actual bombardment of the city is doubtful, but the former battered the outer forts and won the approach.

Antwerp possessed a famous Zoological Garden, and as a precautionary measure the snakes were killed, the dens of the large carnivora being covered with steel netting to protect them from shell fire. Later it was deemed wiser to shoot the lions and other dangerous animals, and the convicts were set free about the same time.

There was no lack of spirit among the gallant defenders, but reinforcements both in men and metal were needed, and England was appealed to.

A good deal of controversial matter blazed out in the columns of the British Press over the subsequent events, but if our answer to that appeal proved to be inadequate, it was at any rate prompt, and it was all that could be given at the moment.

Arrival of British Marines

During the night of October 3rd-4th, a brigade of Royal Marines from Dover (2,200 strong of all ranks) arrived at Antwerp, and early in the morning of the 4th they occupied the trenches facing Lierre, with the 7th Belgian Regiment. They had an advance post on the river, and relieved some exhausted Belgian troops.

The Marines had been cheered to the echo by the people of Antwerp, and the effect of their arrival on the Belgian troops was magical, but unfortunately their coming was too late, although they delayed the enemy's advance and materially aided in the ultimate withdrawal of the Belgian forces.

When our men reached the position assigned to them, the outer forts had already fallen, and the bombardment of the trenches was in full swing.

A particularly desperate attempt had been made by the Germans during the night of the 3rd to force the river at Waelhem, and a pontoon bridge had been thrown across it, but before the German mass had set foot on the right bank the pontoon bridge was shattered, and heavy losses inflicted on the enemy.

In the early morning of the 5th the advance posts were driven in, and the Germans crossed the river at a point that was not under our fire.

The Naval Division

About noon the 7th Regiment of the Line was obliged to retire, leaving the Marines' right flank exposed, but a vigorous counterattack led with great gallantry by Colonel Tierchon, of the 2nd Chasseurs, assisted by our aeroplanes, restored the position late in the afternoon. During the night the Belgians made a determined attempt to drive the enemy back across the stream, but the attempt failed, and the result was the evacuation of almost the whole of the Belgian trenches.

The withering rain of shrapnel and the continued bursting of the heavy shells necessitated our retirement soon after mid-day to another position which had been hastily prepared.

The British forces were under the command of Major-General Paris, C.B., who handled them with great skill, but the thing I was a forlorn hope all the time. Two Naval Brigades had arrived at Antwerp during the night of the 5th in time for some very hot work. The nights were bitterly cold and the trenches half full of water.

The Naval Division had brought guns with, them, two of which were mounted on an armoured train and four 6.5's near the inner forts Nos. 3 and 4.

They had left Dover on the Sunday, and got through to Antwerp just before the enemy cut the line, spending Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday in the trenches, helped by searchlights at night, but all the while existing under conditions that make a young man old before his time.

Their first experience had been an earnest of the rest, for no sooner had they put their baggage into a shed on the quay, when flags were hoisted by a spy, and the shed was immediately ablaze.

Spies in Antwerp

Antwerp swarmed with spies, and it was discovered that many of the outhouses were in direct communication by field telephone with the German advance. Four of these gentry were bayoneted in an attempt to blow up a bridge, and another caught signalling with a lantern inside his overcoat was promptly killed in the trenches.

Two caught disguised as Belgian officers were said to have been court-martialed and shot next day. When the outer ring of trenches became untenable our men fell back upon an inner ring which were supposed to be bomb-proof and lined with sandbags, with covered-in galleries that were very damp and bitterly cold at night, and it was not until the Germans had worked up to within 30 yards of these in overwhelming masses that we were ordered to retire.

It is gratifying to our prestige to know that the defence might have been continued, and possibly with reinforcements conducted to a successful issue, but other influences were at work, and such a defence would have meant the inevitable destruction of the city.

As it was, the enemy had pushed their guns forward, and about midnight on the 7th of October their shells began to fall on Antwerp itself.

Already on the 6th the Belgian troops were withdrawing, and the machinery of the German vessels in Antwerp dock was destroyed by dynamite, the immense oil tanks on the west side of the river being set on fire on the 7th, 50 that the store should not fall into the enemy's hands, the process of drawing off the oil having been found too slow. The conflagration consequent upon their firing added a vivid touch to the horrors of war.

Eye-witnesses speak of the huge triple pillars of smoke rising high into the air from the blazing tanks, smoke which accumulated into a vast black pall overlapping the city itself, retarding the coming of day for hours, until it drifted away to the north-east a little before noon.

The published diary of a petty officer gave some illuminating detail of the condition of things. "No sleep, pitch dark, jolly cold; and suddenly, 'Stand by!' and we peered into the inky blackness for the Deutschers.

"These shells come on like an express train, and then, crash! The spirits of our troops are top-hole, no one the slightest bit excited. Just smoke or yarn and dodge shells, but it's just rotten not coming alongside them."

In another place he wrote, "Our baggage party have just got here. Report the town in flames and all our gear lost. Shells come in like one o'clock. Man on my right side got a bit in his leg, but said he could shoot just as well on one leg."

Antwerp was burning in many places, for the bombardment, which had begun at midnight on the 7th, was kept up without intermission until we evacuated the place.

The Retirement

About half-past five on the 8th, General Paris saw that immediate retirement under cover of darkness was the only thing to he done, and General Deguise, the Belgian Commander, entirely agreed with him. We wished to be the last to leave, but the chivalrous Belgian would not hear of it, and ordered a passage to be cleared for our retirement, which began about 7.30.

It is impossible to improve upon our petty officer's diary, supplemented by some letters from marines and bluejackets. "We had to march back to Antwerp, city in places in flames. Everybody gone. Dead animals in the streets. Shells screaming overhead. Rode through the city over a bridge of boats, which were afterwards exploded, and marched until six this morning. Only one hour's sleep in a small town. Thousands of men on the march, thousands of refugees, Belgians, horses, cattle, and artillery, just like a picture of the retreat from Moscow, and such-like."

A man of the R.N.V.R. wrote, "By God's mercy we got through without being annihilated, and fought our way through the flaming city. . . . Dead bodies and limbs scattered about. It was awful. Two Belgians were blown into pieces right in front of us. The heat of the burning city was terrific. We were lucky in getting two boats to cross the river in. Other boats were burning all round us."

A leading seaman gives the following account "We had to go because there were too many of them. We were ordered to fall in just behind the trenches, and did so just as if we were merely drilling. We took all the ammunition we could, and in our trench we only left three cartridges for the Germans. When we got to the Scheldt we flung into the river all we could not carry, but every man had two or three bandoliers full, then his pouch, and we filled our haversacks in case we had any more fighting to do. . . . By marching quietly we got back the six miles to Antwerp undiscovered. Belgian officers guided us through the town. In some of the streets the heat from the burning houses was so great that we had to squeeze past them on the opposite side of the road."

Incidents on the Retreat

The 2nd Brigade from forts 5, 6, 7 received the warning and got away all right, and the Drake Battalion of the 1st Brigade, which occupied fort 4, was also warned. The rearguard left this fort at half-past two on the Friday morning, some hours after the general retirement, and when they reached the river they found the bridges blown up and everything blazing. Five of them reached Ostend in a dinghy, the rest had to shift for themselves. There seems to have been a bungle somewhere, for the Hawke, Collingwood, and Benbow Battalions never got the order, and continued to hold out in forts 1,2 and 3, until, discovering that they had been left, they made their way back to the river which they crossed on barges, and got the train as far as Lokeren, between Antwerp and Ghent. At that place they were informed that the enemy held the line ahead of them, and leaving the train, they marched, after some rearguard fighting, over the Dutch frontier.

Another detachment which left Antwerp still later had bad luck. They boarded a train already crowded with civilian refugees, got into difficulties a little short of St. Nicholas, and some of the carriages becom- ing derailed and the Germans opening fire, the party surrendered to save the refugees.

The Red Marines

The fortunes of the Red Marines, or at any rate a portion of them, can be found in a private's letter in which he says, "On the retirement from Antwerp we came upon four German sentries asleep. We did not know whether to put them out of 'mess' or not, but, afraid they might make a noise, we crept past them. A little farther along we came to a trench right across the road. Major French crept up on his hands and knees and looked in. He found the trench full of Germans all asleep. We crept along, and, stepping over the sleeping Germans, we all got through the German lines.

We passed through some villages in the early morning, and when we saw a door open we went in. I was the first man in one house, and the woman gave me some hot coffee, and filled my water bottle full of milk. The major got four loaves from a woman. These he divided up amongst the men and went without himself. When we reached our destination we all fell fast asleep in less than five minutes."

From the official account we learn that the rearguard of the Royal Marines also had a similar railway experience at Merbeke in the dark, but the battalion succeeded in fighting its way through with a loss of more than half its number, and after another march of 10 miles entrained at Selzaete.

A private of the 10th Battalion adds a typical touch to this incident in a letter in which he says: "In a short time we ran into a body of German infantry, the train having been turned into a siding. They fired on us and the order was given to detrain. A German officer called on us to surrender. Major French, as fine a man as anybody could wish to fight under, was indignant, and so were all of us. The Major's reply, sharp and short, was 'Surrender be damned! Royal Marines never surrender! ' The order was then given for us to cut a way through the crowd of them. We did, and there was a hot time of it for an hour. We cut them up and drove them back, but we lost heavily, as only 190 of us came out of the scrap."

With the departure of the mixed garrison Antwerp was at the invaders' mercy. The Government had removed to Ostend on the 6th. The whole of the country to the south-east was in ruins; 10 000 buildings had been destroyed by the Belgians themselves in preparation for the defence, and the rest of the villages had been pulverised out of existence by the German guns.

There were between four and five thousand people still in Antwerp on the Wednesday afternoon, but by middle day Thursday a few hundreds only remained, and half a million were in full flight.

That exodus, so thrilling and so full of misery, defies description, and must be passed over as we look at the conduct of the retiring soldiers. The defence of the city and of the Scheldt had been gallant in the extreme. At one place a post was only abandoned when 30 were left alive out of 220 officers and men, and that little band would not retire until ordered to do so by their leader, who was himself killed by shrapnel a few moments later. One regiment was in the trenches for 72 hours. Some of our Naval Brigade held them for 50 hours on end, and whatever carping criticism may have been passed at the time, the fact remains that the Germans scored an empty victory and an empty town, for time had been gained for the Belgian Army and the civil population to get away.

Somewhere about 4 o'clock on the afternoon of Friday, the 9th, the Germans entered Antwerp by the Turnhout and Willryck roads with their bands playing. Some batteries dashed through and, unlimbering on the quay, opened on the rearguard of the Belgians on the other side of the Scheldt. The bombardment of the town had only ended at noon, but with the exception of the Berchem quarter, the damage done was not really considerable. The Cathedral remained practically unharmed, as did also the Museum, the Palace, the Hotel de Ville, and the principal churches and the railway stations. Here and there were ugly gaps among the houses, especially in the Rue aux Lits and the Rue des Peignes. Most of the damage done was due to fire and shrapnel bullets.

A pompous parade of 60,000 troops passed through the city under the eye of General von Schutz, the military governor, and Admiral von Schroeder, who sat on horseback before the Palace in the Place de Meir. It was Brussels over again, and for five hours the squadrons, batteries, and battalions filed by. The military cyclists were the first to enter, and the column closed with a detachment of gendarmes.

From the Cathedral spire the conqueror's flag floated, and the clock hands had been altered to German time, but there was a marked difference in the treatment of the few citizens which remained and that meted out to their less fortunate fellow-countrymen in other places. The German policy was to conciliate Antwerp. Pillage was absolutely forbidden, they paid for what they had, and displayed a certain amount of military civility to the few inhabitants who remained.

Although the censorship wisely concealed the fact for a while, the Marines and Blue-jackets were not the only force sent by Great Britain to Antwerp's aid.

A 3rd British Cavalry Division, under Major-General the Honourable Julian Byng, mobilised at Ludgershall Camp on October the 6th, and sailing the same day for Ostend and Zeebrugge, had disembarked on the 8th. In conjunction with them, Major-General Capper's 7th Infantry Division had landed on the 6th at Ostend, and these two divisions, known for a brief period as the 4th Army Corps, under Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Rawlinson, whose object was to assist the defenders of Antwerp, occupied Bruges and Ghent. Unfortunately, they were too late to effect their object, and had to fall back upon Ypres before an overpowering advance of the victorious Germans, fighting rearguard actions all the way.