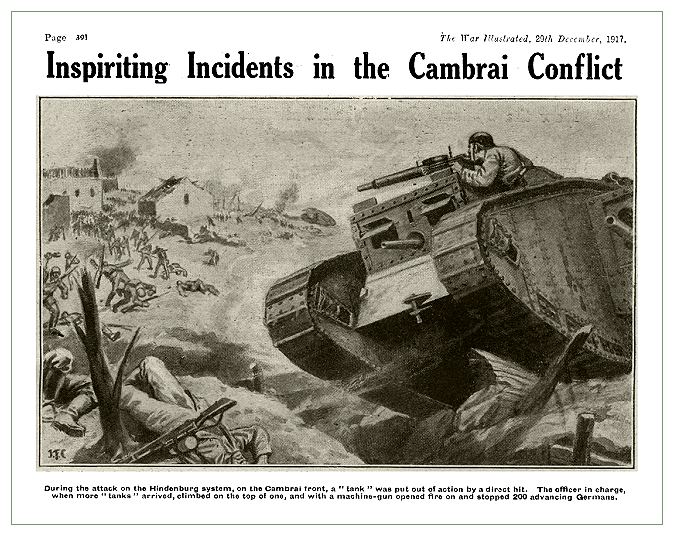

A Battle of Monsters

Illustration of a tank-infantry battle taken from 'the War Illustrated' December 1917.

At the beginning of April, 1918, many of the tank units, which had been in practically continuous action since first March, were withdrawn and sent to the Tank Depot at Erin to refit. Here, after a brief spell of rest, they took over old tanks, overhauled and patched up for the occasion, and returned with them once more to the line, which had formed again as the German advance was checked.

"A" Company of the 1st Tank Battalion was hidden in the Bois l'Abbé, near Villers-Bretonneux. In this sector the Germans had advanced to within seven miles of Amiens, and threatened the capture of that city. If they succeeded, they would cut the Amiens-Paris railway, which was even then being used solely at night, and the solitary railroad left for the British Army would be through Abbéville, only ten miles from the coast.

To prevent this formidable disaster the French had placed their crack Moroccan division, the finest fighters in the French Army, at the danger spot.

In the Bois de Blangy, not far from the Bois l'Abbé, the Algerian and Moroccan troops had dug for themselves very deep and very narrow shelters. These were covered with branches of fir trees placed fiat on the ground, so that it was exceedingly difficult to discover their presence, either from the air or from the ground level.

The first tanks entering the wood in the dark ran straight into the undergrowth, and were considerably alarmed to hear weird yells and shrieks coming from the ground. Terrified black faces popped up on all sides, and the wood suddenly swarmed with strange figures, wh6 had bolted out of their holes like startled rabbits.

Next day, when the machines had been covered with tarpaulins, camouflage nets, and branches, the Moroccans were still not too trustful, and would creep up and gingerly touch the tanks with their fingers - as if to make sure that they were real - and then slink away again.

In the same wood were also detachments of the renowned Foreign Legion, including a company of Russians; and Australian troops, in their picturesque slouch hats, added to the variety of the scene; whilst away in front, for almost a quarter of a mile, stretched an unbroken line of French 75's (the famous quick-firing field gun) mingled with batteries of British I 8-pounders.

On the 17th April the enemy shelled Bois l'Abbé with mustard gas, causing heavy casualties in the forward sections of tanks, whose crews returned with eyes swollen and weeping, and faces and bare knees heavily blistered.

As the German attack was daily expected, a new section of tanks, consisting of a male and two females, was sent to the Bois d'Aquenne, immediately behind Viller-Bretonneux. The wood was drenched with gas, and had been evacuated by the infantry. Dead horses, swollen to enormous size, and birds with bulging eyes and stiffened claws lay everywhere. In the tree-tops the half-stifled crows were hoarsely croaking. The gas hung about the bushes and undergrowth, and clung to the tarpaulins.

On the night of the 23rd of April, the shelling had made the spot almost unbearable. The crews had worn their masks during the greater part of the day, and their eyes were sore, their throats dry.

Then two enemy planes appeared, flying slowly over the tree tops, and dropped Verey lights that fell right in the glade where the tanks were hidden. As the lights slowly flared up we flattened ourselves rigidly against the tree-trunks, not a man daring to move; but it was in vain, for the bulky outlines of the tanks showed up in vivid relief.

We were discovered!

An hour later, when clouds hid the moon, three huge toad-like forms, grunting and snorting, crept out of the wood, to a spot some hundred yards in the rear.

Just before dawn on 24th April, a tremendous deluge of shells swept down upon the wood, and I was aroused in the dark by some one shaking me violently.

"Gas, sir ! Gas !"

I struggled up, half awake, inhaled a foul odour, and quickly slipped on my mask. My eyes were running, I could not see, my breath came with difficulty. I could hear the trees crashing to the ground near me. For a moment I was stricken with panic, and confused thoughts chased wildly through my mind; but, pulling myself together, I discovered to my great relief that I had omitted to attach my nose-clip!

My section commander and I and the orderly who had aroused us groped our way, hand in hand, to the open. It was pitch dark, save where, away on the edge of the wood, the rising sun showed blood red, and as we stumbled forward tree trunks, unseen in that infernal gloom, separated our joined hands, and bushes and brambles tripped us.

Suddenly a hoarse cry came from the orderly: "My mouthpiece is broken, sir !”

“Run like mad for the open!" shouted the section commander.

There was a gasp, and then we heard the man crashing away through the undergrowth like a hunted beast.

Soon I found my tank, covered with its tarpaulin. The small oblong doors were open, but the interior was empty. In the wrappings of the tarpaulins, however, I felt something warm and fleshy, and found that it was one of the crew lying full length on the ground, wearing his mask but dazed by gas. The rest of my crew I discovered in a reserve line of trenches on the edge of the wood, and the crews of the other two tanks, as we found later on, were sheltering inside their machines, with doors and flaps shut tight.

Behind the trenches a battery of artillery was blazing away, the gunners in their gas masks feverishly loading and unloading like creatures of a nightmare.

The major in charge of the battery informed us that he had had no news from his F.O.O. (Forward Observing Officer) for some time, the telephone wires having been blown us. If the Boche infantry came on, would our tanks immediately attack them, whilst his 18-pounders engaged them over open sights ? Our captain agreed to this desperate measure, and grimly we waited.

Meanwhile, as the shelling grew in intensity, a few wounded men and some stragglers came into sight. Their report was depressing: Villers-Bretonneux had been captured, and with it many of our own men. The Boche had almost broken through.

By this time two of my crew had developed nasty gas symptoms, spitting, coughing, and getting purple in the face. They were led away to the rear, one sprawling limply in a wheel-barrow found in the wood. A little later an infantry brigadier appeared on the scene with two orderlies. He also was unaware of the exact position ahead, and, accompanied by Captain I. C. Brown, M.C., and the runners, he went forward to investigate. In ten minutes one of the runners came back, limping badly, hit in the leg. In another ten minutes the second returned, his left arm torn by shrapnel. Twenty minutes after that, walking unhurt and serene through the barrage, came the brigadier and our captain.

The news was grave. We had suffered heavy losses and lost ground, and if our infantry were driven out of the switch-line between Cachy and Villers-Bretonneux, the Germans would obtain possession of the high ground dominating Amiens. They would then perhaps force us to evacuate that city and drive a wedge between the French and British armies.

A serious consultation was held, and the order came Proceed to the Cachy switch-line and hold it “At all costs."

We put on our masks once more and plunged, like divers, into the gas-laden wood. As we struggled to crank up, one of the three men collapsed. We put him against a tree, gave him some tablets of ammonia to sniff, and then, as he did not seem to be coming round, we left him, for time was pressing. Out of a crew of seven there remained only four men, with red-rimmed, bulging eyes, while my driver, the second reserve driver, had had only a fortnight's driving experience. Fortunately one gearsman was loaned to me from another tank.

The three tanks, one male, armed with two 6-pounder guns and machine guns, and two females, armed with machine guns only, crawled out of the wood and set off over the open ground towards Cachy, Captain Brown. coming in my tank.

Ahead loomed the German barrage, a menacing wall of fire in our path. There was no break in it anywhere. Should I go straight ahead and trust to luck ? It seemed impossible that we could pass through that deadly area unhit. I decided to attempt a zig-zag course, as somehow it seemed safer.

Luck was with us. At top speed we went safely through the danger zone, and soon reached the Cachy lines; but there was no sign of our infantry.

Suddenly, out of the ground ten yards away, an infantryman rose, waving his rifle furiously. We stopped. He ran forward and shouted through the flap: "Look out! Jerry tanks about !" Swiftly he disappeared into the trench again, and Captain Brown immediately got out and ran across the heavily shelled ground to warn the female tanks.

I informed the crew, and a great thrill ran through us all. Opening a loophole, I looked out. There, some three hundred yards away, a round, squat-looking monster was advancing; behind it came waves of infantry, and farther away to the left and right crawled two more of these armed tortoises.

So we had met our rivals at last I For the first time in history tank was encountering tank!

The 6-pounder gunners, crouching on the floor, their backs against the engine cover, loaded their guns expectantly.

We still kept on a zig-zag course, threading the gaps between the lines of hastily dug trenches, and coming near the small protecting belt of wire we turned left, and the right gunner, peering through his narrow slit, made a sighting shot. The shell burst some distance beyond the leading enemy tank. No reply came. A second shot boomed out, landing just to the right, but again there was no reply. More shots followed.

Suddenly a hurricane of hail pattered against our steel wall, filling the interior with myriads of sparks and flying splinters I Something rattled against the steel helmet of the driver sitting next to me, and my face was stung with minute fragments of steel. The crew flung themselves flat on the floor. The driver ducked his head and drove straight on.

Above the roar of our engine sounded the staccato rat-tat-tat-tat of machine guns, and another furious jet of bullets sprayed our steel side, the splinters clanging against the engine cover. The Jerry tank had treated us to a broadside of armour-piercing bullets!

Taking advantage of a dip in the ground, we got beyond range, and then turning we manoeuvred to get the left gunner on to the moving target. Owing to our gas casualties the gunner was working single- handed, and his right eye being swollen with gas, he aimed with the left. Moreover, as the ground was heavily scarred with shell holes, we kept going up and down like a ship in a heavy sea, which made accurate shooting difficult. His first shot fell some fifteen yards in front, the next went beyond, and then I saw the shells bursting all round the tank. He fired shot after shot in rapid succession every time it came into view.

Nearing the village of Cachy, I noticed to my astonishment that the two females were slowly limping away to the rear. Almost immediately on their arrival they had both been hit by shells which tore great holes in their sides, leaving them defenceless against machine-gun bullets, and as their Lewis concentrated their fire on us at once we would be finished. We fired rapidly at the nearest tank, and to my intense joy and amazement I saw it slowly back away. Its companion also did not appear to relish a fight, for it turned and followed its mate, and in a few minutes they had both disappeared, leaving our tank the sole possessor of the field.

This situation, however gratifying, soon displayed numerous disadvantages. We were now the only thing above ground, and naturally the German artillery made savage efforts to wipe us off the map. Up and down we went, followed by a trail of bursting shells. I was afraid that at any minute a shell would penetrate the roof and set the petrol alight, making the tank a roaring furnace before we could escape.

Then I saw an aeroplane flying overhead not more than a hundred feet up. A great black cross was on each underwing, and as it crossed over us I could see clearly the figures of the pilot and observer. Something round and black dropped from it. For a fraction of a second I watched it, horrified the front of the tank suddenly bounded up -into the air, and the whole machine seemed to stand on end. Everything shook, rattled, jarred with an earthquaking shock. We fell back with a mighty crash, and then continued on our journey unhurt. Our steel walls had held nobly, but how much more would they endure?

A few minutes later, as we were turning, the driver failed to notice that we were on the edge of a steep shell hole, and down we went with a crash, so suddenly that one of the gunners was thrown forward on top of me. In order to right the tank the driver jerked open the throttle to its fullest extent. We snorted up the opposite lip of the crater at full speed, but when just about to clamber over the edge the engine stopped. Our nose was pointing heavenwards, a lovely stationary target for the Boche artillery

A deadly silence ensued. .

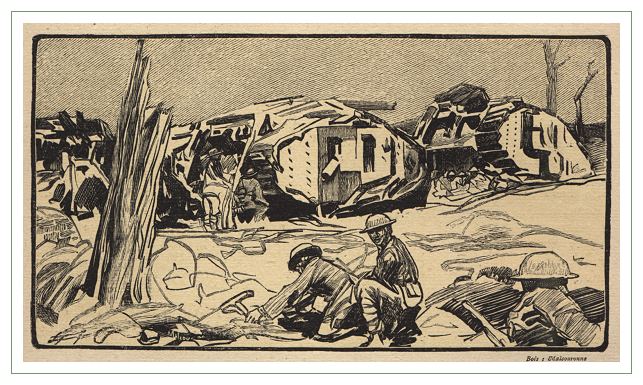

Illustration by Lucien Jonas. A Whippet tank and British soldiers.

After the intolerable racket of the past few hours it seemed to us uncanny. Now we could hear the whining of shells, and the vicious crump as they exploded near at hand. Fear entered our hearts; we were inclined at such a steep angle that we found it impossible to crank up the engine again. Every second we expected to get a shell through the top. Almost lying on their sides, the crew strained and heaved at the starting handle, but to no effect.

Our nerves were on edge; there was but one thing left, to put the tank in reverse gear, release the rear brake, and run backwards down the shell hole under our own weight. Back we slid, and happily the engine began to splutter, then, carefully nursing the throttle, the driver changed gear and we climbed out unhurt.

What sweet music was the roar of the engine in our ears now! But the day was not yet over. As I peeped through my flap.

I noticed that the German infantry were forming up some distance away, preparing for an attack. Then my heart bounded with joy, for away on the right I saw seven small whippets, the newest and fastest type of tank, unleashed at last and racing into action. They came on at six to eight miles an hour, heading straight for the Germans, who scattered in all directions, fleeing terror-stricken from this whirlwind of death. The whippets plunged into the midst of them, ran over them, spitting fire into their retreating ranks.

Their work was soon over. Twenty-one men in seven small tanks overran some twelve hundred of the enemy and killed at least four hundred, nipping an attack in the bud. Three of the seven came back, their tracks dripping with blood; the other four were left burning out there in front, and their crews could not hope to be made prisoners after such slaughter. One broke down not far from Cachy, and I saw a man in overalls get out and, with a machine gun under his arm, run to another whippet, which stopped to pick him up.

We continued to cruise to and fro in front of the Gachy switch-line, and presently a fourth German tank appeared, about eight hundred yards away. The left gunner opened fire immediately, and a few minutes later the reply came swift and sharp, three shells hitting the ground alongside of us. Pursuing the same tactics as before, we increased our speed, and then turned, but the Jerry tank had disappeared; there was to be no second duel.

Later on, when turning again, we heard a tremendous crack, and the tank continued to go round in a circle. "What the blazes are you doing?" I roared at the driver in exasperation. He looked at me in bewilderment and made another effort, but still we turned round and round. Peeping out, I saw one caterpillar track doubled high in the air. We had been hit by the Boche artillery at last, two of the track plates being blown clean away!

I decided to quit. The engine stopped. Defiantly we blazed away our last few rounds at the slopes near Villers-Bretonneux, and then crept gingerly out of the tank, the wounded man riding on the back of a comrade.

We were making for the nearest trench when-rat-tat-tat-tat - the air became alive with bullets. We flopped to the ground, waiting breathlessly whilst the bullets threw up the dirt a few feet away. When the shooting ceased we got up again and ran forward By a miracle nothing touched us, and we reached the parapet of a trench. Our faces were black with grime and smoke, and our eyes bloodshot. The astonished infantrymen gazed at us open -mouthed, as if we were apparitions from a ghostly land. "Get your bayonets out of the way," we yelled, and tumbled down into the trench.

It was now almost one o'clock, and we had been in action since 8.30 a.m., but, so intense had been the fighting, so fierce the unexpected duel, that it scarcely seemed half an hour since we had quitted the gas- laden wood.

We stayed in the narrow trench for a couple of hours, and as the enemy made no further attack, and the officer in charge of the infantry no longer required my services, I decided to return to Company Headquarters.

By this time I had procured a stretcher for the wounded man, and climbing over the parapet we made for home. To our great amazement machine guns immediately opened on us from the wood on our right, practically in the rear of the trench we were leaving. We fell to earth automatically Breathless minutes passed. Then I gave the signal to go forward again, and in some mysterious manner we escaped untouched, even by the heavy shelling.

A hundred yards back we met a team of horses wildly dragging an i8-pounder across the open. The youthful officer on horseback addressed me excitedly.

“I say, old man, I've been sent forward to knock out a German tank. Is that the blighter over there ?" He pointed in the direction of my derelict.

“No," I replied, " you are a bit late ; the German tank is already knocked out.”

“What," he interrupted me, "Already knocked out? Good enough I" and without another word he turned, gave a sharp command, and rode swiftly back, the gun team galloping furiously after him.

I felt immensely relieved to think that he had not been sent up earlier in the day, or my tank might have been heavily shelled from the rear! As it was, we all reached Company Headquarters in safety, and handed over the wounded gunner to a field dressing-station.

For his part in the tank duel, my sergeant, a courageous and cool-headed Scot name McKenzie, was awarded a well-earned Military Medal. The official report contains the following interesting details

"Although his eyes were affected by the enemy gas, and his face badly cut by armour-piercing bullets, in spite of his suffering this non-commissioned officer continued to serve his quick-firing gun for four hours, while his own tank, No.4066 was engaged with large enemy tanks, one of which was eventually put out of action. Throughout, this N.C.O., by his conduct and coolness, set a splendid example to all the men in his crew."

A Military Cross was awarded to me.

see also

Illustration by Lucien Jonas