- from ‘the Sphere’ December 25th 1915

- 'Valse Triste'

- a Sketch Behind a Russian Battery.

- by Scotland Liddell

a British Correspondent with the Russian Army

the Thaw After the Snow in Poland

Mr, Scotland Liddell is the only British artist correspondent who is facing the winter in the trenches witli the Russian armies in Poland. This little sketch of an hour or so behind the lines will bring home to the reader in this country something of the personal conditions existing on the Eastern front. These Russian officers holding their positions between one unpronounceable name and another are just as real, Just as alive to human emotion, as our own "boys" on the Western front. Of course we all know that that must be so, but Mr. Scotland Liddell makes it real to us.

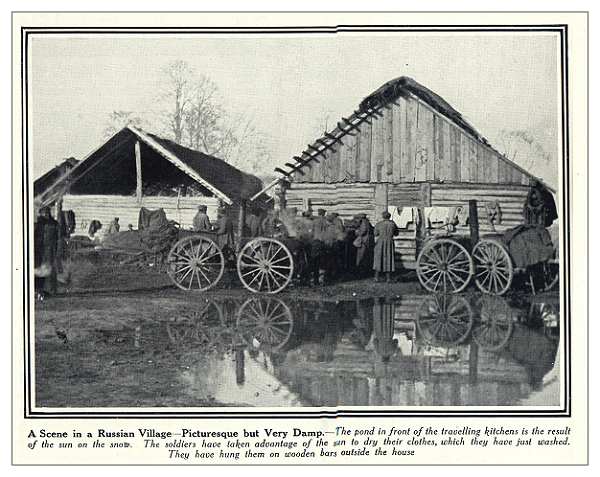

Two hundred yards from the battery the artillery officers lived in a peasant's house. The artillery-men and their horses occupied the rest of the village. And I should explain here that the little "villages" in that part of Russia where we now are, are not villages at all, as we understand the word in England, but rather groups of farmhouses and farmyards belonging to the peasant owners of the surrounding holdings.

These houses are built of logs with roofs of thatch. The floors are simply bare earth. The ceilings and the walls are of plain wood, but on the latter are pasted many highly-coloured pictures of the Saints and of Jesus and the Holy Mother, also of well-dressed, clean-looking Russian soldiers devastating great hordes of the enemy. Such cottage rooms are not the most comfortable places to live in after, for instance, a sojourn in a big hotel, but palaces compared with the stuffy holes in the ground in which so many officers have made their winter homes.

In the Artillery Mess

The artillerymen had similar quarters to those of the officers. More crowded, perhaps, without the trestle beds also, but otherwise the same. They considered themselves lucky. Two versts still further back, a regiment of men had "gone to earth." Four thousand human rabbits in their dark and airless holes. The artillerymen were glad to have real roofs above their heads and real rooms in which to sleep.

More Comfort but Less Safety

There were disadvantages, of course. The village was not quite so safe as the warren. The German shells that missed the battery—they all did ! — were apt to land amongst the wooden houses, and — well, for instance, when I reached the artillery quarters one day I found a square of blackened stone and charcoal. It still smouldered. The previous night when riding "home" across the plains I had seen the great red glow in the sky that marked the burning of the buildings.

A shell had fired them and many soldiers had been hurt. The men who hibernated in the ground had no such dangers as that to undergo.

Riding to Dinner through Miles of Dark Countryside

My engagement with the artillery officers was for dinner. We have that meal in the early afternoon, and when we invite each other to come to dine we always mean "Germans permitting," though we do not say that. I had ridden ten miles across difficult, boggy country from my camp further along the lines. It was damp and cold. A bitter wind. and a thin drizzling rain. I was sorry for myself, and much more so for my horse. He had to carry me, for one thing, and there were bridgeless streams and great pools of yellow water and thin mud to splash through en route. Moreover, he is only beginning to understand English, though he must have heard the sympathy in my voice. We were glad to arrive at the village, although we had to part there. He went off with a soldier— and a piece of lump sugar in his mouth—I with a young commander who conducted me to the house where he and his fellow-officers had their quarters.

Fish and Wine

The room was pleasantly warm. The dinner piping hot. Good broth with a chunk of boiled meat for each of us, and a large bone that allowed us each a taste of marrow. Fresh-water fish from a ready pond (the soldiers find a hand grenade well filled with dynamite much quicker sport than the usual rod and line). Fried meat and potatoes, and a box of biscuits and coffee. The always- present. black bread — before the biscuits came. It is a secret, of course, but we also had a bottle of wine and another of liqueur. Only one of each, and six of us, so what's the harm ?

Listening to the Gramophone

After dinner we sat around the room — the beds were really comfortable seats — and we had a concert, with some of Russia's foremost artists to cheer us, through a gramophone. Chaliapin sang several times — the same songs twice over, also, when we demanded "Bis!" The cannon of a neighbouring battery boomed the applause. Someone gave us a violin solo, and then a huge band played the sweet "Valse Triste" of Sibelius, so that we heard no cracks of rifle volleys, no bursting shells, no big gun fire. Only the waltz — and voices that called to us across the tragic gulf of time.

Coloured Saints Upon the Walls

Outside, the grey, straw-strewn yard and muddy, rutty roads beneath a weeping sky; a wind that sobbed amongst the leafless trees; a sodden roof that shed great splashing tears. Inside, the drab earthern floor; the clumsy, unplaned beams; the coloured saints upon the wall, the little ikon, the Holy Mary, and the Infant Christ; the swords that hung beside the great grey coats and army revolvers that lay in leather holders upon a wooden shelf. And on the beds and on small stools six men, who found the tune well suited to their moods. Sad days — vast skies — a sorrowful refrain.

The Valse Begins

The opening bars came softly, brokenly, with hesitation.

Then came the dreamy sadness of the valse. It echoes in my mind now as I write. Long, plaintive notes — soft — telle tristesse. . . . Then the staccato, with a slow, sweet slurring of the final notes of the movement.

Lonely Men Dream of Home

Across that tragic gulf of time that lay between the days that were and days that seem devoid of hope, my mind went back at one huge leap: A London ballroom, the orchestra behind a bank of palms. A night of light, and sparkle, and laughter, and gay chatter, and sensuous perfume. And this valse. We danced it with the lights switched off, but with a search-lamp spraying a greenish illumination round the room to give moonlight effect.

There came to me in the cottage room the memory of the girl. Dark-eyed, dark-haired, cheeks all aglow with youth and joyfulness of life. Soft arms, and round and white and sweet. The music took a gladder, louder note. Laughter had come to chase the tears away, but still it seemed there was an undercurrent of sorrow beneath it all. Then the valse died away again ; the broken, sobbing notes renewed. The end was so quietly played that one could scarcely hear. A murmured bar or two ; the long-drawn final notes.

A soldier stopped the gramophone. For a few moments no one spoke. One of the officers lit a cigarette. The striking of the match came harsh and gratingly.

"It's a long, long way to Tipperary' ?" one of my companions suggested with a laugh. The song had reached the Eastern front a year ago. Pathos ? Well-if you like.

"That is in England," said I. "Here," I added, and a certain bitterness crept into my voice, "here, it's a damned lot longer to anywhere at all."

"Caracho !" — the Sudden Order Comes

The telephone in the corner of the room buzzed. The commander went quickly to it and picked up the receiver. He gave his division and the number of the battery. Then, "Caracho !" (" All right") he said. The order had come to renew the bombardment of the enemy's lines. So up we jumped. Coats were put on, and swords, and revolvers fastened round the waist. Then out we filed. A young officer ran in advance to give an order to the men.

Out Into the Night

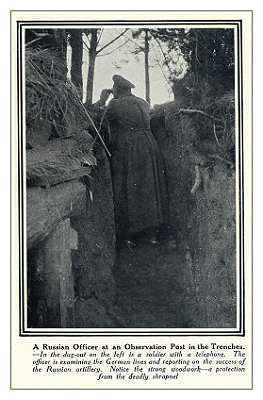

Through the muddy farm village we plashed, across a greasy field and over a brook to where the battery stood concealed amongst a group of pines. The guns were further covered up with fir branches. When we got there the men were at their posts. The guns were all already charged. The gunners waited for a shouted order. The commander cried some words, and then another. Four soldiers each pulled a leather strap. There was a thunder-clap of noise, a lightning flash of light, and four barrels slid back in the recoil like huge pistons. Smoking shell cases were thrown out and four new shells put in. The men again stood waiting. The other four guns had first to fire. After a minute the commander received a message by field telephone. An observer had watched the landing of the shells. The range was right, the aim was good, the shells had had effect. More shouted orders, and then one word. Thunder and flash once more. Smoking shell cases and the reloading of the cannon. Eight guns in all dealing out death to an unseen foe, an enemy that was but a name.

The Broken Spell

The record of "Valse Triste " was still on the machine when we returned to the quarters. We heard the tune again, but the spell had gone. I thought of the success our shells had had. I knew what havoc big guns had wrought in our own lines ; I knew what scenes there were across the way. La tristesse ? It was no sorrow for the foe that filled my heart.

Ten miles across difficult boggy land, with scrubby shrubs and stunted trees — in rain and in the dark. Ten miles with trenches ever near, with rockets rising up to light the sky. Ten miles alone, with roar of guns and continuous rifle fire for ever in from the deadly shrapnel my ears — and the strains of "Valse Triste" running threadlike through all the din of war.

My horse is only learning English, but he's a wonder when it comes to knowing his way home.

- left : in Russian trenches

- right : British reporter Mr. Scotland Liddell