from the British magazine

T.P.'s Journal of Great Deeds

June 26, 1915

SIEGE DAYS IN PRZEMYSL

by Ladislav Gourewitch

NOTE. Mr. Ladislav Gourewitch is a naturalised Canadian of Polish origin. He has for many years been engaged in business at Winnipeg. Early last June he heard of the death of a relative, who had bequeathed him considerable property in Przemysl. About the middle of July he journeyed thither, accompanied by his wife and two young daughters, in order to dispose of the estate, and to give his family the benefit of a pleasure trip. They had barely reached the fortress when the war cloud burst over Europe. Mr. Gonrewitch describes here the thrilling experiences through which they had to live during nearly six months' incessant bombardment. In view of the later developments this article is of special interest now.

Experiences of the Bombardment

The impressions which I carried away from the siege of Przemysl are still confused and chaotic, so rapid were they in succession, and of so overwhelming and tragic a character that it is impossible to tabulate the various events according to their sequence, or even to their relative importance. For six months the forts around the little town were spitting death and destruction night and day from their heavy modern guns, a thunderous roar that shook the earth. For six months the encircling armies replied to the cannonade, pouring daily thousands of shells into the forts and the town. The shells whizzed and shrieked through the crisp, cold air of the endless Carpathian winter nights, and exploded with deafening roars.

A Story of Explosion and Fire

Months passed by, but we lost count of time, so grimly had the nightmare got hold over our nerves and our imagination. The growing spectre of famine became daily more threatening, and disease and epidemics followed in its wake. There was a last despairing effort by the hungry army and its dramatic failure, before the titanic finale on the morning of March 21st, when the beaten Austrian soldiers blew up the bridges and ammunition depots, guns and forts one by one. All day long one terrific explosion after another shattered the windows of the houses. Like craters of a volcano the forts threw up huge masses of steel and rock, and then burst into flame, until the town was encircled by a furious series of conflagrations. It was the last act in life's greatest tragedy. Already the Russians were filing into the town.

Silence that was Unnerving

It was a glorious morning of an early Galician spring. The sun was shining brightly upon the surrounding snow-capped mountains, and upon the heights of the Lopushno-Gorlitza road, where at a distance we could clearly distinguish the Austrian army which had been sent out to relieve Przemysl ! The guns had ceased to speak for the first time in six months. The silence, broken only by the footfall of the grey throng of Russian troops and the clinking of their arms, terrified us. The civilians hid themselves behind the heavily shuttered houses, and gave our liberators a cold reception. Terrible though the bombardment had been, it had become a habit. The sudden silence was a much greater strain upon our nerves, producing hysteria and nausea. The effects were felt for weeks later in a very acute form, and I do not believe that any individual man, woman, or child who passed through the inferno or siege of Przemysl will ever recover quite normal health.

Like a Bolt from the Blue

It all happened so suddenly, so unexpectedly. When I arrived with my family at Przemysl on the 2nd of Suspect August last, it was market-day.

Like a bolt from the blue there came rumours of war, and then war itself. Still nobody troubled in the least. General Kusmanek issued a proclamation reassuring the citizens, and exhorting them to continue their ordinary course of life. The War would be of short duration, nothing need be feared. Moreover, the fortress was impregnable.

Eat, Drink, and be Merry, for To-morrow...

The only difference we noticed was the tightness of money for the first few days. Then followed report upon report of daily victories on the part of the Austrian over the Serbian and the Russian armies. The papers even came out with special editions. All along the line the Russians were driven back, and there were knowing whispers of Moscow and Petrograd. Apparently from nowhere a very undesirable class arrived in the town. Przemysl had become distinctly gay

The Presage of the Ominous

There came a sudden change over the garrison. Though outwardly the pomp and frivolity were still kept up by the authorities, the senior officers looked grave, and officers' wives began to leave. Meantime, more and more military were thrown into the town. Still the papers brought detailed reports of successes, of prisoners and guns taken right down to the fifth of September, when they suddenly ceased publication.

Wild rumours had begun to circulate, and in the distance one could already distinguish the booming of heavy guns. The authorities refused to grant any passports; the roads were blocked by the Russians, who, we had been told, had been driven back into the Arctic snows. A few days later the forts and the town itself were being bombarded. Hell was let loose.

Suspect

Before the complete enclosure of the fortress, I had been called before General Kusnianek. As a British subject, I was of course suspected of espionage. Previous to being brought to the General's presence, I was told by a pompous official that the whole thing was a mere formality, and that I would be sent to the concentration camp at Gran, near Budapest, and separated from my family. The idea of leaving them without protection was too terrible, and I determined to make a fight for the revision of the case.

The Commander of Przemysl

Kusmanek is a tall, powerful man of typical military cut, but with fine, strong features and almost dreamy, dark eyes. My reception was kinder than I had anticipated, and when I had stated my case, he said that he would not separate me from my family, but as I must be acquainted with the defence of the town, I must remain a prisoner within it until the siege was raised. This, he assured me, would not be long, as he shook hinds with me on parting. I ascribed his cordiality and good-will to the fact that he is a Czech, and thus a brother Slav. The only restriction put on my liberty was that I had to keep within the civilian quarter, and forbidden to go near any barracks or defence works. But even this was relinquished later and my wife and I took our share in assisting and nursing the wounded in the military hospitals.

Big Guns and Bayonets

The artillery duel had commenced, and progressed with unbated fury. Sortie succeeded sortie, and assault upon sortie in an unending series. The most brilliant sortie took place on September 25th, when an Austrian attacking column advanced in dead silence, surprising and overwhelming a Russian regiment on the Grodek road. The last and most tragic one, the final effort of despair, occurred on the morning of March 19th, when 20,000 soldiers from the fortress vainly fought for nine hours in an attempt to hack a way through.

Przemysl Had Fallen

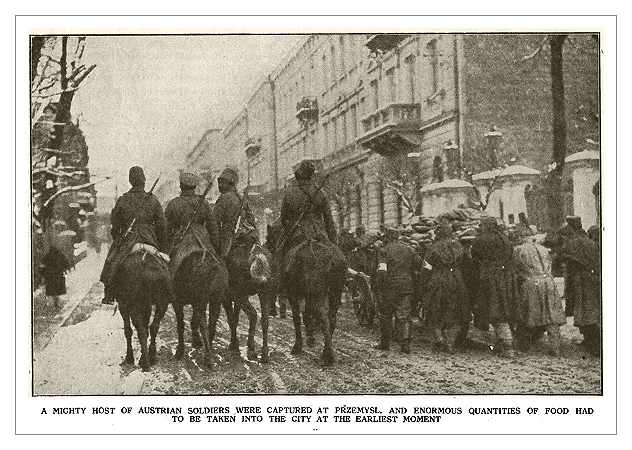

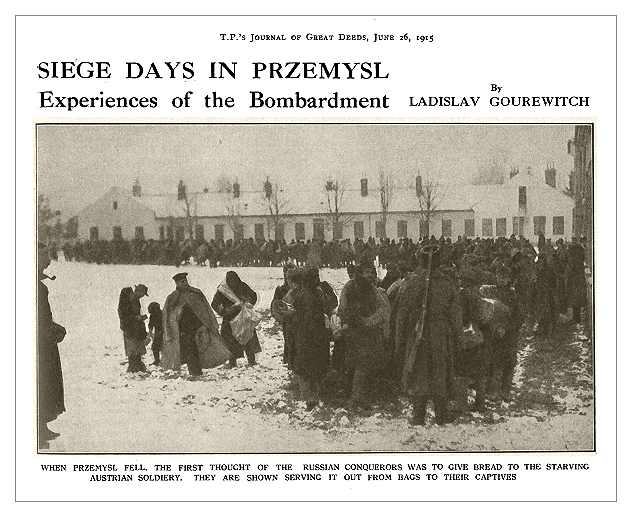

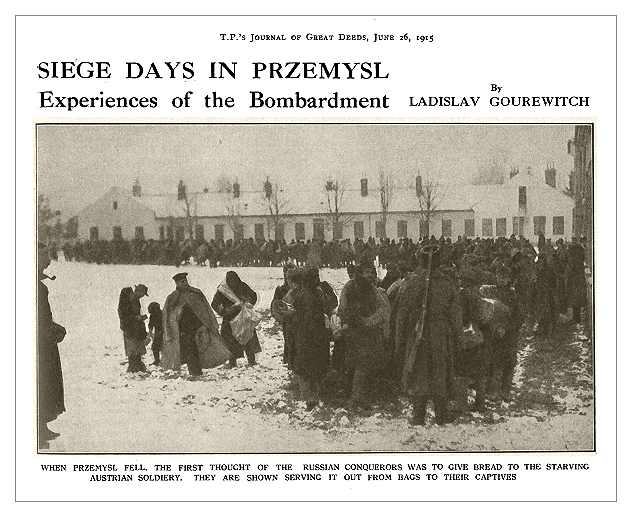

By that time we had already been reduced by starvation, typhus, and enteric, in addition to 10,000 casualties in the hospitals. This was the beginning of the end. The Russians had already occupied heights which were within rifle shot of the outer works, and close upon it they took the principal forts. Przemysl had fallen. When the Russians entered, the condition of the town was indescribable. The last horse had been shot for food, even the General's charger. They were used to feed the civilians.

Kindly and Capable Russians

While one section of the victors disarmed the garrison, the ambulance staff distributed food among us with remarkable skill and rapidity; they grasped the situation, and barely twenty-four hours after their entry they had got everything under complete control, and but for the strange soldiers and the ruins and wreckage, life might almost he said to have resumed a normal aspect. lt was evident, however, that the wounds which the Russian guns first, and then explosions, had caused to the forts would take a very long time to patch up, and it is perhaps better so, for had the town had to stand a second siege there would not be one brick left on top of the other.

As far as my personal affairs are concerned, I have left them to look after themselves, glad, after our terrible experience, to have come out of it with our lives. There is one certainty, however: I shall never again come to Europe in search of a fortune.