From

The History of the Great War

vol. IV published by Waverley Book Co. Ltd

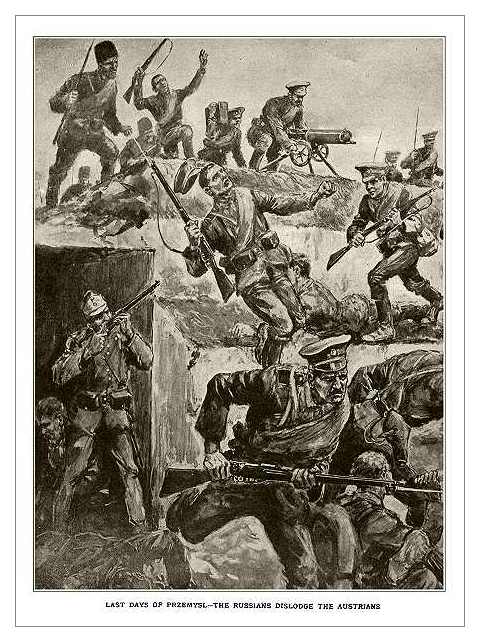

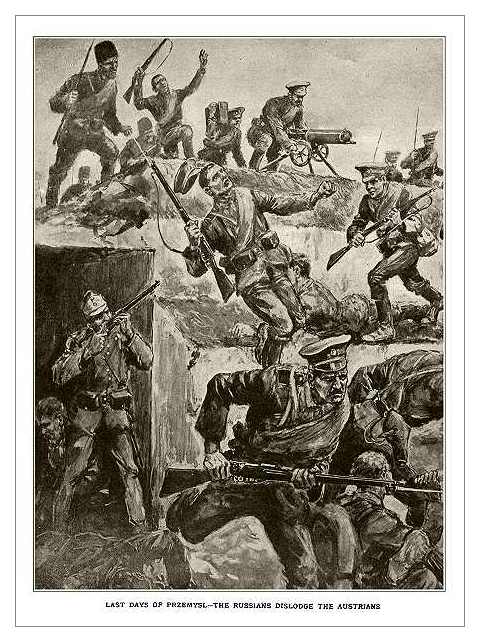

Russians storm the Przemysl forts

BEGINNING OF THE SIEGE OF PRZEMYSL

First Siege of Przemysl

Unable to advance by these means, the Austro-Germans found their attempts at the relief of Przemysl quite unavailing, and we must now turn our attention to the siege of that fortress. We shall have enough and to spare of the fighting elsewhere in Galicia in later pages. To get the story in its true perspective we must glance back for a moment to the beginning. As we remember, Przemysl first came prominently into the piece after the fall of Lvoff. The shattered Austrian army, flying from that city, escaped, one half through the Carpathians, the other half towards Przemysl and Cracow. Just how the division numerically was effected none quite knew save those in the confidence of the enemy. Certainly nobody dreamed that a great host, fleeing within the shelter of the fortress walls, had remained inactive there. But that is what actually happened. Seventy thousand or eighty thousand men more than the fortress ought ever to have contained rushed within the ramparts and there remained. This meant that, with the garrison, there were 150,000 men in Przemysl. That number was diminished during the many sorties, by deaths, wounds, disease, and prisoners taken, by some 30,000 and odd. But there remained to the last over 120,000 officers and soldiers within the walls.

An Immobile Army

The presence of such a host, armed as this fortress was with some of the finest ordnance in the world, and supplemented by all the guns and siege train brought in by the army which retreated from Lvoff, should completely have defied capture. But, by one of the almost incredible examples of Austrian and German ineptitude, the whole vast garrison was allowed to remain immobile and to be slowly pressed farther and farther within the successive rings of defences, and starved into the most abject of surrenders.

Of course, the capture was not achieved without cost to the besieging army. After the first great successes of the Russians in Lublin and before Lvoff, they leapt forward at Przemysl, intending to carry the place by storm. But they found themselves confronted by defences among the strongest in existence. For two or three weeks they hurled themselves at those defences, and sustained very severe losses. What those losses actually amounted to the Grand Duke never formally published. The Germans declared the number to be at least 70,000, which was, possibly, a characteristic exaggeration. But the figure was undoubtedly high. And for the time it achieved nothing. For, early in October, a new Austrian offensive began, and, owing to the consequent rearrangement of Russian forces, the siege had temporarily to be raised.

It was at this juncture that the crowning indiscretion of the higher Austrian command was committed. The gates were thrown open to their field army. Supplies of food and ammunition poured in, ammunition for the defence of the garrison, ammunition intended for the siege of Russian cities. So far so good. But they left there all the seventy thousand men who had fled from Lvoff. These could have been at this time safely withdrawn to join forces intended to operate in the open against the adversary. They were left there to eat their heads off, so to speak. If Przemysl was to be regarded as a starting-point for an Austrian army, now was the time for such an army to start; Austria needed it badly enough in all conscience. But some sinister fascination caused these men to take root in Przemysl, to wait in idleness and to share the food which the garrison proper required. There was over a fortnight in which a decision could have been reached as to how best to dispose of the surplus of fighting men within the walls. Nothing was done. The Austrian defensive was beaten back; the unnecessarily idle seventy thousand did nothing. The Russians came trooping back to fasten anew their tentacles of steel around the doomed city.

Midway through November the Austrians tried a second time from the Carpathians to set free the city, and on this occasion the huge garrison joined in. All the passes from the Dukla eastwards passed into the keeping of the Austro-Germans, and the garrison, breaking out in a fierce sortie, endeavoured to link up with the oncoming relieving forces. It speaks volumes for the magnificent fighting of the Russians that they supported and overcame the pressure from the two sides. The enemy advancing from the mountains pressed forward to within two or three days' march of the outer works; the garrison, working out fifteen miles from the city, must have been desperately near them.

Yet our Allies succeeded in inflicting a smashing blow upon the garrison, drove them, broken and bleeding, helter-skelter with huge loss back to their shelter, and simultaneously crushed the Austro-German advance from the Carpathians. Reading later of tight corners into which waves of Austro-German aggressiveness thrust the Russians in Galicia and elsewhere, the memory of that fighting in. Galicia for the fortress was a considerable balm for the anxious mind, for the Russian success in the face of these very serious perils was huge, and will long be remembered when the war drum throbs no more. Thereafter the Russians contented themselves with regular operations. They passed the entire winter before the walls, a winter of mud and slush and snow and frost and fog, with the great guns of the city constantly playing upon them, with aeroplanes passing overhead with villainous bombs, with the enemy from a dozen quarters striving to reach and help the prisoners out.

The garrison was entrenched upon principles new to the defence of citadels. They were engirdled by successive circles of forts and earthworks, the outermost perimeter having a circumference of between forty and fifty miles. The defences were so constructed that the works ran underground like a colossal warren, miles upon miles of subterranean galleries bomb-proof and impregnable, as it was thought. By means of these widespread unseen ramifications it was possible to make sorties in many directions from points quite unexpected by the besiegers. So far from the innermost works were the outermost, that when these sorties were made each party would be absent at least two nights. At times the sorties met with small successes, and these were magnified into great victories. We were told from time to time of Herculean efforts made by the besieged, who were represented as bursting forth and carrying back so many thousands of Russian prisoners that we wondered how many armies Russia really had before the strong place. The humiliating fact for Austria was that the investing army numbered, at times, actually fewer than the army assembled within the fortress.

No city was ever better provided for defence. The forts, all linked up on the most scientific principle with railways and what not, the best of explosives in unlimited quantities a host of doctors, and medicaments enough for a campaign as well as a siege; but it had also a fleet of aeroplanes and dirigible as well as many observation balloons. And, for the first time in the history of war, a regular a aerial post was maintained between the colossal defensive force in men, with the fortress and headquarters. Aeroplanes flew to and from Przemysl day by day. They carried dispatches; they even carried; supplies in small quantities. One brought just before Christmas bore luxuries for the military governor's dinner. With a little touch of old- world chivalry, General Selivanoff, the general commanding the Russian army before the fortress, having captured his enemy's Christmas dinner, sent in a goose and other delicacies, under cover of a flag of truce, so that the fortunes of war should not deprive his rival of the treasure for which he had looked. Otherwise the siege was conducted with all the rigours of war, honourable war that is, war as made by the Allies. There was no attempt to poison the defenders' water supply, no firing of explosives containing asphyxiating gases, no treacherous tricks under the Red Cross or white flags. These things did not come within the scope of the Allies' plan of campaign, for they were fighting as the old Crusaders and knights errant fought, with a modern variant of the old "you fire first, gentlemen, please" idea.

All that the Russians could do was practically to fight sitting. They were wholly outmatched in the duel between the big guns, for the Austrians had an enormous superiority in this particular. In some of the main forts were 13-inch and 14-inch guns, worked by electricity and automatically disappearing after firing. The smaller redoubts were furnished with motor batteries, armoured machine guns and crowds of quick- firers. The least of the forts were of reinforced concrete, artfully concealed from an enemy. Picture these defences and contrast them with the relatively puny guns of the Russians and some notion of the war between the contending forces is gained. The question, naturally, arises how was it that Austria should be in possession of so vastly powerful a place in the heart of one of her own provinces, seeing that the best fortresses in Belgium and France had proved hopelessly inadequate and out of date. The secret is that, during the Balkan war, she was prepared to take a hand, if the opening could be found, and to this end she remodelled Przemysl; while the field defences, first discovered at Liege to be a necessity, were improvised after the outbreak of the Great War.

Austria's Fine Artillery

The Russians, wise after their sanguinary initial experiences against the defences, approached by the most approved methods of trench warfare. With their best guns skilfully disposed to meet the most likely line of sorties, they built themselves in, forming shelters suggested by the course of events in Flanders, but based in the main upon the old Russian native genius for defensive-offensive warfare. Little by little, under cover of their shelters, they sapped up to the outer defences, and by fine courage and skill won them, yard by yard. And when they arrived they stayed. To do so required considerable nerve and endurance, for the garrison fought with great vehemence, as may be inferred from the following description, from the pen of an Austrian military writer, outlining one of the general engagements : "It is true that Przemysl belongs to the most modern and strongest defensive works in Europe, but the main credit of the defence rests with the Austro-Hungarian artillery, which was served with wonderful precision. The 12-inch howitzers, in particular, speedily silenced every enemy battery brought into position.

Artillery duels were continuous, and in these the guns of the fortress remained in undisputed mastery of the situation. With the aid of well-posted observation stations and of a splendid system of aeroplane reconnaissance, the positions where the enemy had begun to establish batteries were speedily detected and then subjected to heavy bombardment. Every promising target was bombarded, such as columns on the march, points where reserves were concentrated, etc. and this the defending batteries were well able to do, thanks to their lavish supplies of ammunition."

In spite of all obstacles, however, so skilfully and gallantly was the Russian artillery worked that, as stated, the outer defences were. captured and the investing army clung unweariedly to the work of repelling sorties and working ever a little nearer. Their position was always precarious, for so splendid were the defences that at all times by day the redoubts could sweep the spaces between them with a fire so deadly that it was impossible to cross them, while at night brilliant searchlights lit up the same troublous pathways. But there was no gainsaying this Russian Army now. They could have carried the place at any time within the last six weeks of the siege, but the cost would have been far more:. terrible than that which the Japanese paid for Port Arthur, and so the waiting fight was practised.

Plight of the Garrison

Slowly the food of the garrison diminished. Fresh meat for the rank and file gradually disappeared. All sheep, cattle and other domestic animals, including horses, save those of the officers, were killed and eaten. There remained only tinned meats, and these, though welcome where other supplies were lacking, gained an unenviable re- putation for themselves and for their purveyors.

At last the end of the food stores was in sight. General Kusmanek, the military governor of the fortress, doled out extra supplies for a few days; extra sugar, extra tinned food. This, apparently to stimulate courage for a great surprise. The bulk of the garrison were called upon to embark upon despair's last journey. They were to make a sortie. They were to fight their way to food, the food reserves of the Russians lying eastward of the fortress. Each man was given a blanket, each man who needed them was given a new pair of boots, with sugar for five days and other food accordingly. And each was told that, come what might, he must not return!

It was in quite a nice little address that General Kusmanek sent his men to their deaths- if such it should prove.

The Final Sortie

But, for all the fine talk, not the whole garrison, nor nearly all of it, was flung out; but only some 20,000 men. They were turned with their heads in the direction where food lay, Russian food. When the Servians crossed the Danube and captured Semlin, we were told by the Austrians that these little people had so acted because they needed food. Now they were trying the food-bait as an inspiration for the emaciated soldiery of Przemysl. But did it mean that? Prisoners, asked why so many footling little sorties, each bound to end in bloody failure, had been tried, made replies suggesting that in their opinion it had been necessary to reduce the garrison in this way! Be that as it may, the idea of this last great sortie was hopeless and absurd. Twenty thousand men could not prevail against the Russians, and if they had, there remained only three days' food behind for the rest. The sortie was a last unnecessary sacrifice of brave men's lives. Sternly met by the Russians, the expedition sustained a loss of over 3,000 killed and wounded and about as many prisoners. If effected nothing, it could not have effected anything. It was a wanton piece of brutal melodrama, a suggestion of fighting to the last gasp - and making helpless privates pay with their lives for the unholy pageant. After this wicked immolation of gallant men upon the altar of military tradition, Kusmanek set to work to blow up bridges and forts, then sent out his Chief of Staff to the Russian Commander to ask for terms. Finally, the place was yielded up unconditionally, as the Austrian Commander said, "In consequence of the exhaustion of the provisions, stores, and in compliance with instruction received from my supreme chiefs."

The Dignity of Victory

The Russians entered as soon as might be, not to gloat over their triumph, but in order to convey food to the starving civilians and soldiery. They took as prisoners, in addition to General Kusmanek, 126,000 officers and men, and were left with over a thousand guns, 700 of them of considerable calibre; but, of course, not nearly all in working order.

It was all over on March 22nd, and Russia had achieved her most romantic and sensational coup of the war, so far as the latter had then progressed. There were still dark and troubled days before her. For the present she was entitled to her hurried hours of happiness and self-congratulation, and there were hymns of thankfulness in the hearts of her Allies when the Tsar and his staff sang a solemn Te Deum at their headquarters.