from

The Great War in Europe

by Frank R. Cana F.R.G.S

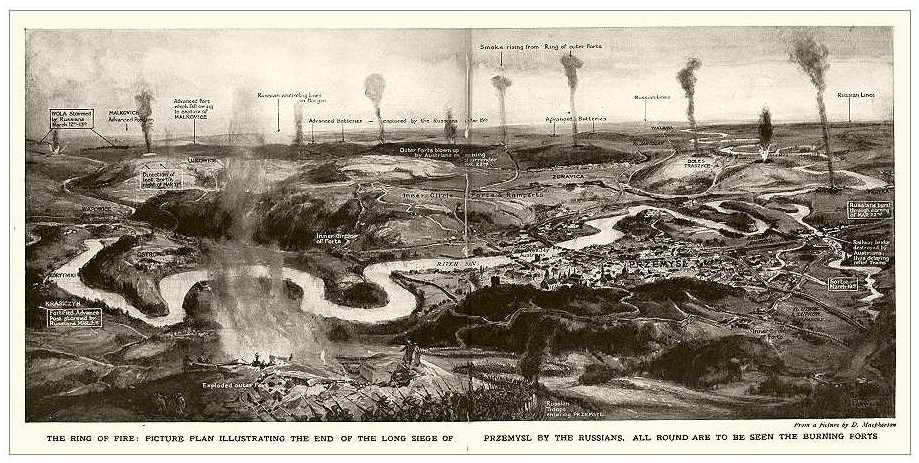

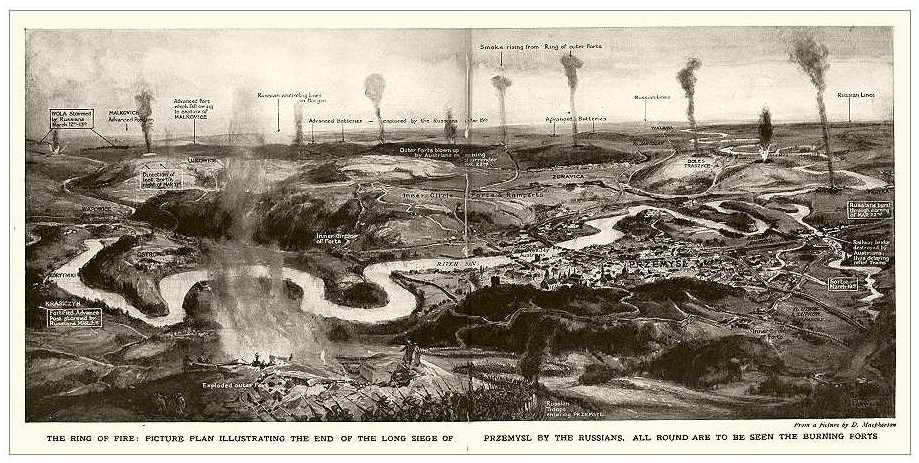

a panoramic view of the fighting during the Russian siege

CHAPTER XIII

SIEGE AND FALL OF PRZEMYSL

Importance of Przemysl -The Fortress Described - Its Huge Garrison - Brussilof's Assault in September Fails with Heavy Loss - The Siege Raised in October - Przemysl's Provisions Used to Feed the Field Army - Przemysl again Invested in November - Relief Expeditions all Fail - The Sortie of December - Hope Revived: a February Sortie - Privations of the Garrison - Well-Fed Officers - The Final Effort to Break Through - A Dash for Food-Blowing up the Forts - A Wonderful Scene - Surrender of the Fortress, 22nd March 1915 - One Hundred and Twenty-three Thousand Prisoners - Russia Rejoices.

PRZEMYSL was first attacked by the Russians in September 1914; it was not until the 21st of March 1915 that it capitulated. Its siege and its surrender are one of the outstanding events of the Eastern campaign. The importance of the fortress may be gauged from the fact that for four months the efforts of Austria, aided by large German forces, were concentrated on an unceasing endeavour to prevent it falling into the hands of the enemy. When, in September 1914, the Russians swept victoriously through Eastern Galicia towards Cracow, Przemysl alone defied them; when, after having been compelled temporarily to fall back, the Russians in November were again victorious in Galicia, Przemysl still flew the Austrian flag. While Austria held Przemysl, not only was the Russian advance hampered, but the moral effect of the conquest of Eastern Galicia was lessened. Przemysl stood as a symbol indicating that Austria might yet regain what she had lost. The Galician peasants, well disposed to Russia as they were, pointed to Przemysl and said, "The Austrians will come back."

The fortress, if it did not bar the Russians' road to Hungary, was a stumbling block in their way, and while it and Cracow held out the Germans had little fear of an invasion of Silesia. Austria-Hungary was right in regarding its retention as a cardinal point in the campaign against Russia, but, at the outset, no special measures for its relief were taken. It was hoped that the course of the campaign as a whole would automatically relieve Przemysl. When, in mid-November, Marshal von Hindenburg began his second thrust at Warsaw, German and Austrian armies also advanced from the front Czestochova-Cracow, and had their offensive proved successful Przemysl would have been freed. In Galicia, however, the Austrians were unable to advance farther than the Dunajac tributary of the Vistula They could not get, that is, within ninety miles of Przemysl, and it thus became clear that special measures would have to be adopted if the place was not to be left to its fate.

In December 1914 operations were accordingly begun having as definite object the relief of the beleagured fortress. The Russians, leaving an army to "contain" Przemysl, had advanced into the Carpathians. Raiding parties had even entered the great Hungarian plain and larger bodies had overrun Bukovina. What we may call the Przemysl Relief Expeditions advanced therefore via the Carpathians. In any case it was essential to prevent, if that were possible, the Russians obtaining the mastery of the Carpathians; this was part of the Austro-German task whatever might be the fate of Przemysl Indeed the struggle in the Carpathians went on months after Przemysl had fallen. Despite their utmost efforts, none of the armies sent into the Carpathians to the rescue of Przemysl were able to afford it any help. It met its fate alone, and we may therefore the more properly deal with it as a separate episode in the war, reserving to later chapters the record of the Carpathian battles. To make the narrative complete, we tell the story from the period when Przemysl was attacked by General Brussiloff's army in September, giving first some slight account of the place itself.

Przemysl is the chief fortress of Eastern Galicia. It lies in a valley in a hilly, wooded region, part of the northern slopes of the Carpathians, and is built on both banks, but chiefly on the right bank, of the upper San, here spanned by three bridges. It is of great strategic importance, being 60 miles south-south-west of Lemberg and 150 miles east- south-east of Cracow. It is a junction for many roads and railways, but it does not absolutely command the communications between Eastern and Western Galicia. The townspeople trace its origin back to the eighth century A.D., but it owed its former importance to Casimir the Great of Poland, who built its fourteenth-century castle, now in ruins. In modern times its inhabitants, Poles and Ruthenes, have made it a busy trading mart, and it is one of the centres of the Galician oil fields. The surrounding country is rich agricultural and fruit farming land.

Its modern fortifications were immensely strong. The outer forts cover a circle some thirty miles and within their limits are several villages, farms, woods, and fruit gardens. Everything within and without the forts which interfered with the line of fire had, however, been destroyed by the defenders. The nearest of the outer forts being five miles from the town, Przemysl itself was throughout the siege free from the danger of being shelled. The townsfolk and the villagers living within the fortifications numbered about 50,000 and were able to pursue to a large extent their usual avocations. The commander of the fortress was General von Kusmanek, the second in command being General Tamassy, chief of the Honved (Hungarian) forces. Kusmanek had, however, a much larger force at his disposal than was needed for defensive purposes. When the siege began the garrison had been added to by the arrival of many of the regiments of the armies of von Auffenberg and the Archduke Joseph Ferdinand, defeated in the first Galician campaign, and further troops were poured in until over 150,000 men were gathered at Przemysl. This was done so that General von Kusmanek should have one or two army corps ready to aid the Austrian field armies. For defence alone 60,000 men would have been ample.

With a recklessness reminiscent of the first assault on Liege by the Germans, the Russians sought at the outset to take Przemysl by storm. After the fall of Lemberg General Brussiloff advanced to the San and sent a parliamentaire to the commandant of the fortress calling upon him to surrender it. Kusmanek replied that his duty was to defend and not to surrender the place, and he added a polite invitation to the Russians to come and take Przemysl if they could. Brussilofi's army had performed prodigies of valour, and though without heavy siege guns, they proceeded to attack the outer forts. They perished in thousands; and they failed. The defenders, aided by their great howitzers, had no difficulty in beating back the Russians. Valour availed the attackers nothing, and in three or four days Brussiloff had over 20,000 casualties. Taught by this experience, the endeavour to carry the fortress by assault was abandoned. Instead, the Russians began a regular siege, and by 27th September they had completely invested the place. Almost immediately there followed the advance of the Austro-German armies on Ivangorod and Warsaw, and the Russians were compelled to withdraw. They still remained in the neighbourhood, but by 11th October Przemysl was relieved. On that date General Boroevich entered the fortress with his army. The Austrians, 'following' close upon the retreating Russians, did not foresee the rapid change which was to take place, and that before the month closed they would themselves again be in retreat. Their first step, therefore, was to use Przemysl to supply the needs of their troops at the front. The Austrians fighting to the east of Przemysl were provisioned - both with food and ammunition - from the ample stores of the fortress. There was no other available source of supply, for the Russians had blown up the railway lines connecting Cracow with Przemysl. With great energy the Austrians set about reconstructing the railways, and on 23rd October trains carrying ammunition to make good the depleted stores of Przemysl began to run.

Then came the turn in affairs in Poland; both Hindenburg and the Austrians were forced to retreat in great haste, and at the beginning of November, before the deficiencies in food had been made good, Przemysl was again invested. The Austrian General Staff subsequently explained that during the ten days they had command of the train service to Przemysl "the transport of ammunition took first place" and they sent in huge quantities. Kusmanek lacked neither powder nor shot right through the siege. "At that time," the Austrian Staff added, "the question of provisioning the fortress appeared to be a secondary matter. When eventually food supplies were dispatched it was too late." Why the supply of food was considered a secondary matter was not explained; we may conjecture that the Austrians felt confident that the fortress would be relieved before it felt too acutely the pangs of hunger or they may have argued that an army with plenty of bread but little lead was worth less than an army with plenty of lead but little bread. Yet it was the lack of bread and not the lack of lead which caused the fall of the fortress.

Once the Russian ring had closed for the second time around Przemysl that question of food assumed overwhelming importance. The fortress had been crammed with soldiers, each of whom had a mouth to be filled; moreover, there was the civilian population also demanding food. Advantage had been taken of the raising of the investment to remove some of the townsfolk, but the majority were allowed to remain. There can be little doubt that the Austrians, during those days of wasted opportunity in October, looked upon Przemysl not as a place about to be again besieged, but as a base from which field operations were to be undertaken.

General von Kusmanek soon found that there was little chance of the fortress playing such a part. The Przemysl was complete by 12th November, pierced thereafter. That was in the sortie we shall presently describe. We may here give the composition of the garrison, which included some of the crack Hungarian regiments. There was the 23rd Honved Division (the Division of Versacz), the Hungarian Artillery Division, a brigade of Austrian cavalry, the East Galician Landwehr, Northern Hungarian and Galician Landsturm, a number of Croatian regiments, and part of the 1st Austrian Landsturm Artillery.

The fortifications had been planned on the most scientific lines. Between the twelve outer forts numerous batteries were placed and the spaces between were covered with entanglements, trenches, and moats. The fortress possessed 16 armoured works, including 48 with calibre to 6 in. The 48 armoured works were for the defence of the flanks, and 20 others were for the defence of the moats. Nothing had been neglected to make the armament adequate to the needs of so large a fortress. Austria until 1913-14 did not use steel for making cannon, and in 1909 her field artillery was rearmed with bronze guns, upon the system and manufacture of which Austrian technical science justly prided itself. Although there were some 300 iron guns, which, if old-fashioned, were in good condition and serviceable, the majority of the guns at Przemysl were bronze, including 235 fortress guns and 352 field guns. Among the latter were 28 modern quick-firing guns. Heavy-calibre guns were represented by 4 modern howitzers of 12 in. and 8 howitzers of 24 cm. Obviously the capture of such a fortress was no light matter.

Investing Przemysl the Russians had an army of about 100,000. General Ivanoff, the Commander-in-Chief of the Russian armies in the south-west, had the supreme direction of the investing force, but the operations were conducted by General Selivanof, who was chosen for the task because of special knowledge of siege warfare. Under his orders the Russian positions were fortified with, in the words of their enemies, "unparalleled skill and rapidity, and with all available means of modern technique." The Russians, according to the Austrians, built "a new fortress" all round the besieged territory. Though there was in this statement a touch of exaggeration, the Russian lines around Przemysl were made exceedingly strong. General Selivanof did not attempt to take the place by storm, but proceeded by regular siege methods sapping up to within a few hundred yards of the outer forts.

Perhaps the most singular thing about the siege was its comparative uneventfulness. There were, however, two stirring periods one in December, the other just previous to the surrender. In December the Austrian field army advanced through the central Carpathian passes, driving the Russians back, and occupied the town of Sanok. General von Kusmanek thereupon ordered a sortie in the hope of joining hands with the field force. There was no difficulty in timing his movements, as he was in constant communication by wireless telegraphy with the Austrian General Staff The sortie was made on 15th December by some 30,000 troops, who broke through the Russian investing lines to the south-west of Przemysl. This force not only broke through but, maintaining its communications with Przemysl, advanced to Bircza, some fifteen miles beyond the outer forts. It was less than thirty miles from the relieving army, but got no further, for General Selivanof brought up reinforcements which, after a sharp fight on i9th December, drove the Austrians back to the fortress, with a casualty list exceeding 3,000. For a couple of days the situation had been serious for the Russians.

The detachment from Przemysl had nearly succeeded in gaining touch with their comrades in the Carpathians; the field army could hear the thunder of the guns of the fortress. The danger the Russians met and overcame, and Christmas within the fortress was no time of joy. The season was, nevertheless, marked by an exchange of courtesies. To give one example, an Austrian aeroplane flying towards Przemysl, brought down by the Russians, was found to carry nothing but Christmas presents for General von Kusmanek's staff, and these were sent to the Austrian lines. A sortie made at the end of December was repulsed without difficulty, and during January the garrison was for the most part quiescent.

Early in February hope revived in the beleagured garrison. A strong Austro-German force swept up the Carpathians in a manner which suggested that it would break through the Russian defences. It indeed gained the Tucholka Pass (the pass immediately east of Uzsok Pass) but was fought to a standstill in a series of terrible battles at Kosziowa. Before this happened there was a good deal of confidence in Przemysl that the end of their trials was in sight. A wounded Russian prisoner, in hospital at that place, noted in his diary (subsequently published in The Times) that on 10th February rumours were current that an army of 800,000 Austrians was advancing and that 2nd March had been fixed as the date on which the fortress would be relieved. To keep the enemy engaged General Selivanof, who had by this time been supplied with heavy siege guns, severely bombarded the outer forts. This action Kusmanek interpreted as a sign of anxiety, and he ordered a sortie for 17th February; the sortie was made, but was unsuccessful. At the end of the month the general learned that the Austro-German offensive had failed. There was no chance of a new movement for the relief of the garrison being organised before famine had done its work, and Kusmanek received orders on the exhaustion of his food supplies to destroy the forts and guns and surrender.

By mid-March the troops were reduced to the verge of starvation, though hundreds of the Austrian officers were still well fed. Well groomed and in spotless uniforms they frequented the cafés of the town, played cards and billiards, and refused to share in the hardships of the men. Doubtless all were not callous and heartless, but the thing which most nauseated the Russians when they entered the place after its surrender was the sight of these dandies sauntering in the streets, sleek and comfortable, while their famished men were fighting over the carcasses of horses, smeared with blood as they devoured the raw flesh, just as the naked Africans fall upon an elephant newly shot by a hunter, nor leave it while a morsel of meat remains on the bones. As early as November the men were put on short commons. The dietary was: for breakfast, tea only, no food; for dinner (midday), "a small piece of meat and half a pound of bread"; for supper, "tea and some bread." According to the Austrian General Staff the rations were the same for officers as for men, but it appeared that the civilian population were not put on rations and that officers were able to buy goods in the town up to the last, or almost the last, day of the siege.

Not until February was well advanced did the food situation become desperate. Most of the horses had then been killed and eaten; later on all the cows were seized. The Russian soldier to whose diary we have referred notes on 21st March, "our Mother Superior (who was in charge of the hospital) sold a cow for £140 and a three-day-old calf for £12. A dog costs £2.

There was no bread left; the wounded were being given the last of the biscuits; the soldiers for dinner had only beetroots. Yet numbers of officers still contrived to obtain three good meals a day and retained their thoroughbreds. These horses, some 2,000 in number, were only killed the day before the surrender, and then not for food, but to prevent them falling into the hands of the Russians.'

In Vienna the question had been raised in the early days of the siege as to the possibility of provisioning Przemysl by aeroplanes. It is an interesting point, and the statement of the Austrian Staff thereupon deserves quotation. We take the Morning Post’s translation of the document :

"It has been said in some quarters that flying machines and dirigibles might have been used in bringing in supplies, but this idea was excluded from the beginning. Such flour or meat as could have been thus brought in would only have sufficed a few hundred men for a few days, and to have made any appreciable difference all the aeroplanes and dirigibles of the world would have had to have been employed daily. The commander of the fortress vetoed the idea that certain members of the garrison should receive food by this means whilst the rest put up with the rations available in the fortress. Even the game shot by some of the officers was not allowed to be brought in, but was cooked and eaten in the hunting field. [So the officers had their game too!] The aeroplanes only brought in letters, medicines, and material for the wireless telegraphy."

General von Kusmanek, if he failed to instil a sense of decency and humanity into his officers, was a brave man, though his conduct of the defence was not marked by brilliant strategy. When the state of the garrison was at its worst he ordered a final sortie. Since 10th March the Russians had bombarded the fortress with great guns, and had captured Wola and Malkovice, posts beyond the outer forts. The troops taking part in the sortie were exclusively Hungarian. They formed the 23rd Honved Division, comprising the 2nd, 5th, 7th, and 8th Regiments. The Hungarians had throughout been the soul of the defence, and the Hungarian officer was more ready than his Austrian brother to share the hardships of his men. What appeared to be a strange proceeding on the part of General von Kusmanek was that the sortie was made to the eastward, towards Mosciska, that is in the direction away from the Austrian field army. The explanation was given by a member of General Selivanof's staff, who stated that Kusmanek believed that the provisions of the besiegers were stored at Mosciska-and the first requisite of the garrison was food. The sortie was made at 5 A.M. on the i8th of March. The Hungarians fought with the traditional ardour of their race, but they were met with a pitiless, accurate, and sustained fire from the Russian artillery, in face of which they could make no progress. They never reached the Russian trenches, and at two o'clock in the afternoon retired within the line of their own forts. The sortie cost the loss of 3,500 in killed and wounded, besides 4,000 men and 107 officers taken prisoners. On the night of the 18th the Russians captured another of the Austrian advanced posts, and by the 20th the concrete works of the outer forts had been almost all destroyed.

The end drew very near. An Austrian aeroplane captured on 20th March contained correspondence which showed that General von Kusmanek had abandoned hope. He did his best to carry out the final instructions from the Austrian Staff to leave to the enemy nothing but a heap of ruins. During 19th to 21st March military stores of all kinds were burnt. All through the night of the 21st the artillery fired to get rid of its ammunition, while part of the garrison tried in vain to break through the Russian lines. The final scene was enacted on the 22nd. At five o'clock in the morning of that day the Austrians began to blow up the forts and magazines and to destroy the great guns. Hundreds of the guns were thrown into the San, together with thousands of rifles whose stocks had been broken. The noise caused by the blowing up of the forts was appalling; the house which, twelve miles away, was occupied by the Russian Staff was shaken as by an earthquake. Accounts of what this eruption looked and felt like have been given from without and from within. A Russian Staff officer, whose narrative was published in The Times, wrote :

"At 6 A.M. I went out and ascended a small hill to look at Przemysl. A wonderful picture was spread out before my eyes. The morning was calm and a warm sun was rising in a clear sky. Above the fortress there hung a pall of smoke, and from it every now and then rose columns of black smoke, thin like poplars, but capped at the top like mushrooms. They looked wondrously beautiful in the sunlight."

The Russian soldier in hospital, whose diary gives so vivid a description of Przemysl in its death throes, writes-he was a cool man to keep a diary on such a day - as follows :- "Marek 22.-The fortress is surrendering. At 5.30 A.M. explosions were heard, at first separately, but later a regular hell was let loose. We opened the windows so that they should not be broken. The sun had already risen, and the plumes of smoke, lit up by the sun, presented a beautiful scene. The thunder and crash of the explosions went on uninterruptedly. It was impossible to get near a window; one was flung backwards. The panic had become terrible. At every explosion the doors were blown open. Bridges, powder magazines, stores, everything was blown up in two hours. The Ruthenes were overjoyed at the Russian victory. We could no longer remain in the hospital, and for the first time we went out into the streets. Our soldiers were embracing the Austrian soldiers. In one place a ring had been formed and our cavalry men were dancing with the Ruthene women. All the footpaths were thronged with people."

One of the last acts of the Austrians was to blow up all the bridges - those over the San and the railway bridge over its tributary the Wiar, though by blowing up this last bridge no military purpose was served. All it did was to delay the Russians bringing up food for the starving garrison from Lemberg. Having completed as far as he could the work of destruction, General von Kusmanek sent the chief of his Staff to the Russian headquarters, announcing the unconditional surrender of the fortress. Immediately afterwards Kusmanek and his Staff drove up in motor cars to the Russian headquarters. General Selivanof treated his prisoners with honour, and afterwards they were sent to Kieff, where they were interned. Meantime by ten o'clock in the morning the Russian cavalry were in the town, and the first care of the conquerors was to give what help was immediately available to the starving troops. Later in the day General Artamonof, until then military governor of Lemberg, arrived to assume his new duties as governor for the Tsar of the fortress of Przemysl, which the Russians renamed Permysi, a much more pronounceable word!

No fewer than 123,000 soldiers were in Przemysl when it surrendered. The magnitude of the garrison occasioned the Russians surprise. A dispatch from the Grand Duke Nicholas, dated 6th April, said : "All the prisoners taken at Przemysl have now been removed."

Altogether there have been sent into the interior of Russia 9 generals, 2,307 officers, and 113,890 rank and file. In addition to these, about 6,800 sick and wounded are being cared for in the hospitals in the theatre of war, their condition being such that they could not have borne an immediate journey. To attend to them 129 surgeons and 100 hospital orderlies of the Austrian army have been provisionally kept at the front."

In addition over 6,000 men of the garrison had been taken prisoners before the surrender. As the total force under General Kusmanek was over 150,000, the loss of the besieged in killed and died of wounds or disease between 1st November and 22nd March was about 20,000. The Austrian figures tallied fairly closely with those of the Russians, save that they asserted that no fewer than 45,000 of the prisoners were not soldiers in the strict sense of the word but "workmen - drivers, railway and telegraph men militarised under the War Service Law." Besides the prisoners the Russians found in Przemysl over 1,000 guns, but so thorough had been the work of destruction that only 180 of them were fit for use. A quantity of shells and a large stock of rifle cartridges were discovered undamaged.

No official information as to the Russian casualties was forthcoming. We have already stated that in the abortive assault in September General Brussiloff lost fully 20,000 men. After the regular investment began in November, the Russian casualties except in repelling the sortie of 15th December were comparatively light.

It is unnecessary to enlarge either on the depression caused in Vienna and Budapest by the fall of Przemysl, or the rejoicing with which the news was received in Russia. The Austrian military critics declared that their armies in the Carpathians would take up the r6le of Przemysl and form a bulwark against the Russian advance. The Austrian army did take up that task with unflinching courage. Nothing could, however, disguise the significance of the loss of the fortress. A solemn "Te Deum" celebrated at the headquarters of the Grand Duke Nicholas, was attended by the Tsar, while in Petrograd the churches were crowded with thanksgiving citizens. Nor was this acknowledgment of Divine sovereignty an empty form with the Russians. The sincerity and, one may add, the simplicity, of their faith was a source of strength to the Russians.

The story of Przemysl did not end with its surrender to the Russians; ten weeks only had passed when it was recaptured by an Austro-German army. The account of that exploit, and of the ultimate fate of the fortress, is told in a later volume.