Paris Mobilizes

from a French newsmagazine, 'Le Miroir' issue

37, August 9th 1914

- top : ethnic Czechs in Paris proclaim admiration of

France

- under : requisitioning horses and vehicles

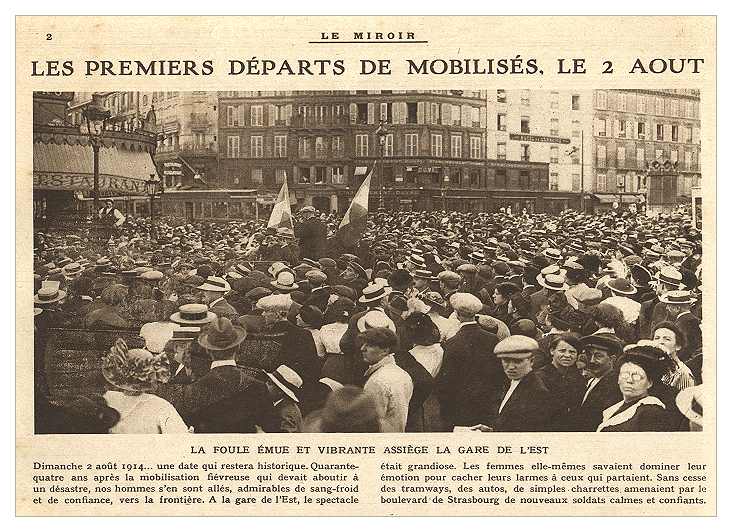

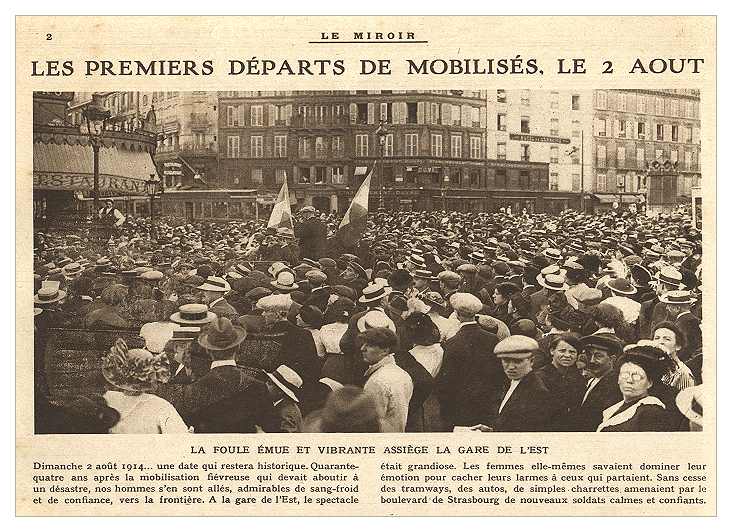

- top and under : the first levy of mobilised recruits at

the Gare de l'Est in Paris

-

- 'As our train passed

through France on its way to Nancy, we

heard and saw the tumult of a nation

arming itself for war and pouring down to

its frontiers to meet the enemy. All

through the night, as we passed through

towns and villages and under railway

bridges, the song of the Marseillaise

rose up to the carriage windows and then

wailed away like a sad plaint as our

engine shrieked and raced on. At the

sound of the national hymn one of the

officers in my carriage always opened his

eyes and lifted his head, which had been

drooping forward on his chest, and

listened with a look of puzzled surprise,

as though be could not realize even yet

that France was at war and that he was on

his way to the front. But the other

officers slept; and the silent man, whose

quiet dignity and sadness had impressed

me, smiled a little in his sleep now and

then and murmured a word or two, among

which I seemed to hear a woman's name.

-

- In the dawn and

pallid sunlight of the morning I

saw the soldiers of France

assembling. They came across the

bridges with glinting rifles, and

the blue coats and red trousers

of the infantry made them look in

the distance like tin soldiers

from a children's playbox. But

there were battalions of them

close to the railway lines,

waiting at level crossings, and

with stacked arms on the

platforms, so that I could look

into their eyes and watch their

faces. They were fine young men,

with a certain hardness and

keenness of profile which

promised well for France. There

was no shouting among them, no

patriotic demonstrations, no

excitability. They stood waiting

for their trains in a quiet,

patient way, chatting among

themselves, smiling, smoking

cigarettes, like soldiers on

their way to sham fights in the

ordinary summer manoeuvres. The

town and village folk, who

crowded about them and leaned

over the gates at the level

crossings to watch our train,

were more demonstrative. They

waved hands to us and cried out

" Bonne chance !" and

the boys and girls chanted the

Marseillaise again in shrill

voices. At every station where we

halted, and we never let one of

them go by without a stop, some

of the girls came along the

platform with baskets of fruit,

of which they made free gifts to

our trainload of men. Sometimes

they took payment in kisses,

quite simply and without any

bashfulness, lifting their faces

to the lips of bronzed young men

who thrust their képis back and

leaned out of the carriage

windows.

-

- The fields were

swept with the golden light of

the sun, and the heavy foliage of

the trees sang through every note

of green. The white roads of

France stretched away straight

between the fields and the hills,

with endless lines of poplars as

their sentinels, and in clouds of

grayish dust rising like smoke

the regiments marched with a

steady tramp. Gun carriages moved

slowly down the roads in a glare

of sun which sparkled upon the

steel tubes of the field

artillery and made a silver bar

of every wheel-spoke. I heard the

creak of the wheels and the

rattle of the limber and the

shouts of the drivers to their

teams ; and I thrilled a little

every time we passed one of these

batteries because I knew that in

a day or two these machines,

which were being carried along

the highways of France, would be

wreathed with smoke denser than

the dust about them now, while

they vomited forth shells at the

unseen enemy whose guns would

answer with the roar of death.

-

- Guns and men,

horses and wagons, interminable

convoys of munitions, great

armies on the march, trainloads

of soldiers on all the branch

lines, soldiers bivouacked in the

roadways and in market places,

long processions of young

civilians carrying bundles to

military depots where they would

change their clothes and all

their way of life - these

pictures of preparation for war

flashed through the carriage

windows into my brain, mile after

mile, through the country of

France, until sometimes I closed

my eyes to shut out the glare and

glitter of this kaleidoscope, the

blood-red colour of all those

French trousers tramping through

the dust, the lurid blue of all

those soldiers' overcoats, the

sparkle of all those gun- wheels.

What does it all mean, this

surging tide of armed men ? What

would it mean in a day or two,

when another tide of men had

swept up against it, with a roar

of conflict, striving to

overwhelm this France and to

swamp over its barriers in waves

of blood ? How senseless it

seemed that those mild-eyed

fellows outside my carriage

windows, chatting with the girls

while we waited for the signals

to fall, should be on their way

to kill other mild-eyed men, who

perhaps away in Germany were

kissing other girls, for gifts of

fruit and flowers. '

-

-

- from : Philip

Gibbs ‘The Soul of the

War’ 1915

Back

Introduction