- from 'Everyweek Magazine' April 25th, 1918

- 'An Englishwoman in Paris'

- by Marie Harrison

Bombarded by the Mystery Gun

damage caused by 'the Paris Gun'

"You will find Paris depressing - it has changed absolutely since the beginning of the war."

That is what a Frenchman in London told me before I left England. I went to Paris expecting to find a city of sorrow, and instead I found a city of smiles. Superficially, Paris may depress. There is no gaiety in dress, no social life, no hankering after amusement. Paris shuts up at half-past nine. There is the wearing of mourning in every street. Yet I found Paris brighter than London, I found it more alive, more interested and so more interesting.

No Food Problems

There is no food talk in Paris because there are no food problems. Bread and sugar are rationed, and while the sugar allowance is less than ours, the bread allowance is ample, even for the French. For the rest there is plenty of everything. Butcher's shops are filled with red, juicy meat; in restaurants you are always served with at least three different kinds of cheese. Butter at six francs a pound is not much dearer than it was before the war, and the little dairies, so widely scattered in Paris, are full of the best produce of Brittany and Normandy. Fruit and vegetables are cheap and plentiful. Indeed, the only food problem is the milk problem, and supplies are distributed to the best advantage, because milk is not allowed to be served with tea or coffee after nine in the morning. Invalids and children are thus able to have the first claim.

Tobacco Queues

The only queues in France are tobacco queues. Cigarettes are extremely scarce, and the urchins of the streets make fortunes quickly if they happen to discover a shop where tobacco is on sale - for they rush to the boulevards and tell the American soldiers, who are supposed to be rolling in wealth, where the smokes are sold.

That is one reason, then, why Paris is cheerful. There are no food difficulties, and so none of the depression which comes from a constant battle to provide well-balanced nourishing meals when meat and butter and fish and bacon are dear and scarce.

Paris is more cheerful than London because of her trust. Parisians talk, I know. They are intensely vivacious and gay, but they are less inclined to criticise than Londoners. They follow every movement at the front with breathless interest. They buy newspapers as quickly as they appear. They adore maps. But they have trust. They are willing to leave the conduct of the war to soldiers. They are not armchair critics. And for that reason I think they are less inclined to be depressing than the Londoner who would like to direct the war from his suburban allotment.

Dressmakers in the Trenches

In London the talk is mostly food talk or war talk of a singularly dull character. The Parisians talk about art, or music or the new books or the new plays. In London there is an extraordinary display of dress. Often I have wandered along Oxford Street, marvelling that after almost four years of war the shops should be able to show such glories. It is very different in Paris. Evening dress is not worn, and even the rich do not wear costly clothes. They dress quietly, in dark colours or in black. It would be impossible to see in Paris crowds of beautifully dressed women spending an afternoon gazing in shop windows. All the great dressmakers ore either at the front or designing dresses of modest simplicity. They would feel it undignified and distinctly unpatriotic to make elaborate frocks while the war continues. They content themselves with tailor- made coats and skirts or house wraps of severely plain design; if some of the dressmakers still do turn out wonderful creations these are intended rather for London and New York and the towns of South America than for Parisians themselves.

Dress of all kinds is expensive. A ready-made costume such as you could buy in London for five pounds costs almost double in Paris. Shoes are costly. The plainest type of straw hat is seldom marked at less than twenty francs. So it has come about that Parisians who do not dress quietly because of their natural good taste do so because they are obliged to in these days of scarce materials and high prices. You see more well dressed women in Piccadilly in a day than you see in the Champs Elysees in a month.

Early Rising

Paris is an earlier city than London. It happened that I had to make an appointment one day over the telephone with an official of the Ministère de la Guerre. "Don't come too late in the morning," he suggested, "I should say about nine o'clock." Well, I went at nine o'clock and found that this energetic man had already seen three other visitors. I doubt if that would be possible in London, where it is difficult to find any Government servant at work, or at least ready to be seen, before eleven o'clock.

But Paris is up and about very early. The last trains on the Metropolitan railway run about eleven at night, and Paris is abed soon after. Go into the railway again at seven in the morning and you will find it crowded with men and women on their way to work. This all makes for cheerfulness. Paris wants to get through its day's work energetically and quickly so that it may enjoy the long evening hours of light. I should think it a hardship in London to start the day earlier after my experience of Paris.

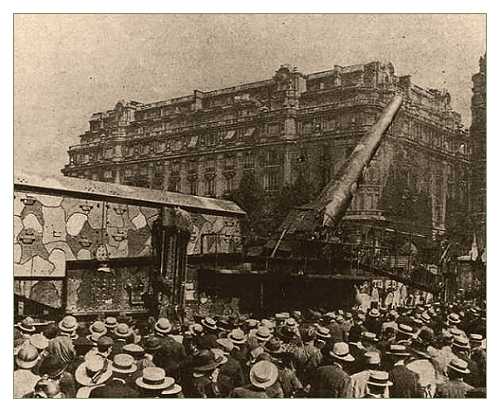

a German railway gun captured and on display in Paris

The Mystery Gun

I was in Paris during the first days of the bombardment, and I know something about the morale of the city under circumstances of acute unpleasantness. Air raids are horrible enough but they have their time limit. There is no "all clear" in an attack by the mystery gun. I remember that on Good Friday it began early in the morning, and the explosions continued throughout the day, occurring precisely at every quarter of an hour. That is a form of irritation which the Huns thought would empty Paris in a week. Some people left the city as some people have left London to escape the raid. But the greater number of Parisians went quietly about their work and did not even leave the business at hand to seek shelter from the approach of the next expected attack. Paris is so close to the war and has lived for so long beneath its shadow that it would take more than a long range-gun to disturb the normal course of its way of living.

Refugees

The most pathetic phase of Paris which I saw was the arrival of refugees from the land which we have had to give up on the front. These unhappy people have been driven from their homes after living for two years under the rule of their own people. First there came to them in August of 1914 the terror of the German invasion, and for two years, they lived with that terror day and night. Then there came the happiness of liberation in those great days of the battle of the Somme in 1916, and now these victims of war have been driven away from their houses by the German advance, and I saw them, poor exiles, flocking into Paris with, their bundles and their children and their animals, as I saw the refugees flock into Brussels in the first days of Armageddon. Our soldiers are splendidly cared for in Paris. The Leave Club, a fine hotel taken over for the purpose, is crowded every day with men on rest from the trenches. The Canadians have a magnificent club which was previously a famous hotel. The decorations and the furniture remain, so that the humblest private has all the luxury which he would have if he were an American millionaire seeing the sights of Paris.

Religious Revival

Something must be said about the churches, for no picture of Paris in wartime would be complete without a word about the great revival of religious feeling. The churches are full to-day as they never were in peace time. And you see soldiers as well as civilians kneeling in prayer, men as well as women. And all the prayers that are offered and all the candles burnt as a votive offering are for one end only and that is for Victory.

That is what Paris thinks of and longs for and prays for, and nothing else matters. The small things have all been put away, and the gaiety which you find in Paris is the gaiety which comes not from artificial amusements but rather from that quiet repose which is the result of a national soul that has found itself, and that awaits the issue of these critical times in a spirit of tranquil confidence and hope.

Marie Harrison