of Spies and Things

Dastardly Deeds and Unsporting Behavior

from a British newsmagazine : spy-mania in print

from the book :

The Secret Corps

by Ferdinand Touhy 1920

EXPERIENCE in the war showed that whereas it was comparatively simple for an intelligent agent to collect information with everyone about him or her more or less intimately concerned with, and discussing, some aspect or other of the struggle, it was a very different matter, and an extremely complex one, getting such information through to the state employing one, in time for it to be of any use, or indeed, to get it through at all. One might say that war was declared more on a spy's communications than on the spy himself, since it mattered little what information an agent succeeded in collecting if he were unable to pass it on.

The nature of a spy's communications depended principally on whether he was employed in the big cities or behind the lines.

In the early days in France and Flanders, several strange means are said to have been resorted to by agents desirous of communicating across the lines. They sound comical enough to-day, but we need to bear in mind and compare the altered circumstances then and towards the end. In those days not only was the Entente anti-spy organisation in the field hopelessly inadequate, numerically, to deal with a war zone seething with unknown civilians and voluntary helpers in uniform, but its members were themselves floundering in ignorance, learning things from hour to hour. Undoubtedly things occurred which-well, never can occur again. The spy made hay. If an agent had a wireless apparatus, it may still, in 1914, have been possible for him to have used it skillfully and to have escaped detection. Established behind the Allied lines, a spy certainly could have received instructions as transmitted to him in code by German wireless stations situated back in Belgium and Northern France. Whether he, in his turn, could have transmitted information to enemy receiving stations is another matter.

Though at the beginning of the war the Allies possessed no effective system of policing unauthorised wireless, and messages of grave consequence may have actually been sent out by spies, on the other hand it should be borne in mind that the working of a wireless transmitting apparatus is in itself no light matter. Petrol and a motor are only two of many requisites necessary, and the difficulty in obtaining the former was as serious an obstacle as was the likelihood of the engine being overheard, a danger. At all events, if undetected wireless ever flourished on the western front, which is doubtful, its reign was extremely brief.

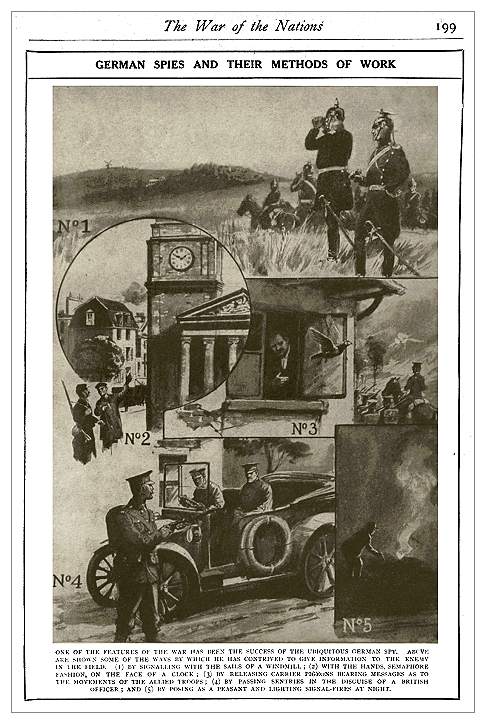

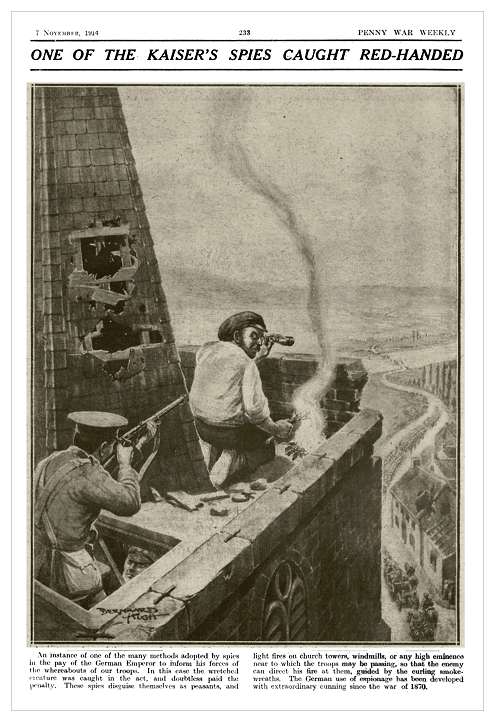

In the British zone, Flemish peasants in German pay and German officers masquerading as Flemish peasants, are popularly supposed to have evolved diverse substitute methods of communicating across the lines.

There was the case of the nun of Vlamertinghe reported to signal by emitting puffs of smoke from her chimney whenever British troops were passing through the village, so that the German gunners might find a good target.

Then there was the balloon scare.

Little balloons would be seen, sometimes at a great height, being carried by the wind over to the German line, there, according to our wiseacres, to be shot down by waiting Germans who would collect messages attached to the "basket." So instructions were issued that all such baby balloons were to be brought down by British fire before they crossed the lines.

And there were many other scares. The ploughed field scare for one.

This originated in the imaginative mind of a Royal Flying Corps officer who suggested that it was possible to signal up information to a pilot or observer by ploughing a field in a certain way and in conformity with a certain pre-arranged code. Thus, if a field were ploughed in "tiger stripes," that might indicate to German pilots flying overhead, that the British were preparing to attack locally. And there were many other ways of ploughing a field-in fact, not to plough it at all might easily have meant "all quiet in this sector." In practice, thought our imaginative officer, German aviators would be sent over daily to watch and report on the condition of certain "spy-fields," or better still, they would be instructed to photograph such fields for a detailed examination of them to be carried out subsequently by experts on terrain. The idea seemed feasible enough back in 1915, and so started a ploughed field scare. R.F.C. observers were detailed to make a complete photographic survey of the rear of our lines, the prints thus assembled being forwarded on to headquarters for pasting into a consecutive whole. The panorama of fields and woods and roads was then minutejy studied through a magnifying glass like a magic-lantern apparatus, lest any peculiarities in local ploughing had developed.

Sometimes when suspicion arose in connection with a certain field, an intelligence officer would be dispatched to question the peasant owner regarding his artistry with the plough, which may have contributed in some measure to the popular Flemish notion that the English were brave but mad.

Then there were those wicked, treacherous human hands, moved by German gold, and said to manipulate the clock on Ypres town hall so as to convey information to the enemy.

The clock was always wrong, argued the scare-mongers, and unquestionably the burgomaster of somewhere or other hard by was a villain and a traitor. Whatever the foundation for that scare, it was terminated abruptly by the Germans putting a shell through the clock tower. Possibly they had been dissatisfied with the information derived from this particular source.

A more serious alert concerned windmills, with which the Flanders countryside is, or was, dotted.

It was realised that whereas with chimney smoke and ploughed fields one could signal but the broadest information, such as "fresh troops arrived" or "no fresh troops arrived," with the arms of a windmill, now slowly manipulated, now more speedily, a system of signalling on the dot and dash principle was feasible. This was actually done by way of a test, and after that most civilians living. adjacent to windmills visible to the enemy were either evacuated or a day watch was set on each windmill so exposed.

Other possible forms of civilian signalling had to be enquired into from time to time. In the autumn of 1915, suspicion was aroused as to the continued presence of women in pitilessly shelled and broken hamlets like Brielen in the Ypres salient. Why did these women remain on, surrounded by death and misery ? Spies, clearly some of them must be spies! The writer remembers once being despatched to report on the nefarious practices of these women of Flanders. The first nefarious practice alleged was that these women, most of whom earned a livelihood by doing laundry-work for the troops, periodically signalled to hostile observers overhead by spreading out their "washing" to dry in certain fixed. shapes. Thus, one day a field would be covered with a vast circle of shirts, the next by an equally vast cross of pants. The scare was accentuated' by the arrival of a 28 c.m. shell in the centre of a company of the Monmouths marching on the Brielen road, by which the entire company became casualties - the worst single round one recalls having heard of in all the war.

The vigil of Brielen's women was continued by night since light signalling across to the enemy had also been reported. Lying out drenched and stiff through a Flanders' night one watched for a blind to go up or for a lamp to flash. But the women of Brielen evidently slept soundly in their beds that and every other night. Neither the laundry nor the light signalling scare ever came to anything.

Then there was the pigeon scare. The Germans were certainly using carrier and homing pigeons for intercommunication with spies! Orders were accordingly promulgated that every pigeon or anything approaching a pigeon in appearance, was to be ruthlessly crashed. That there was a deal in this specific scare was subsequently emphasised by the slaughter of a pigeon dyed green and red like a parrot-in order, clearly, that it should escape massacre. The expert and intimate examination of this comrade-in-arms at 14th Corps headquarters remains a vivid memory. Beneath a dazzling electric light the Corps Commander, Lord Cavan, and his Staff craned their necks in a circle while an Intelligence officer, whose wife kept pigeons in Surrey, delivered an impromptu lecture on "methods resorted to in concealing messages on pigeons."

Next day one was confronted by an alert of a very different kind. Two German soldiers in divers suits were captured by the Belgians north of Merckem. These daring souls had actually waded across the flooded stretch of country separating the lines and had been two days installed behind the Belgian position, noting every detail of our ally's front line organisation, before they were discovered in a shell crater. Though they had minute hand-drawn maps of the Belgian sector in their possession and also. .copious notes, the two were treated as ordinary prisoners of war. One wonders if the Germans, on discovering two Allied soldiers dressed as divers and spying in their rear, would have stretched things so magnanimously.

If two Germans could thus pierce the line, obviously others could, and so a "beat" was organised through Flanders fields and villages for masquerading Huns.

There were many other alerts. An especially important one concerned the possible existence of secret telephone lines passing, say, from an inhabited town like Armentieres, out through No Man's Land, hardly a mile away, and so on into the German lines. The examination of dozens of disused lines close up to the line was no light affair.

Then again, as "Z" day approached at Arras in 1917, the notion became imbedded in local staff craniums that civilian inhabitants, of whom a few score still persisted in living on in the battered and gassed town, were communicating across the lines with the enemy by using (a) dogs, (b) fish as carriers.

It was snowing heavily at the time of the dog scare, and any morning an Intelligence officer might have been seen minutely studying canine footprints in the snow around Arras, whence they came, where they led to, etc., prying in fact, into perfectly private animal life. The anti-fish crusade was a more elaborate affair. At Arras, the Scarpe flows gently east, i.e. towards the German lines. What simpler than for a piscatorial spy to catch a fish, cut it open, insert his report, and then throw deceased back into the river? In an hour or so the dead fish or the dead dog or a wooden box or anything for that matter-would have reached the German lines. Accordingly, three nets, each of varying thickness, were spread across the Scarpe at Arras, and every day a close scrutiny would be made of all the nasty rubbish they collected.

In animal life war was declared on both the living and the dead. Orders were given that all dogs seen straying near the line were to be shot. At one period quite a legendary tale arose round "the grey dog of Armentieres"-a veritable hound of the Baskervilles. This quadruped was reported to be a German police dog trained to pass through the opposing trenches and report to some civilian spy, with nice fresh meat, in Armentieres, and then trot back to "Hunland "bearing the latest military information tucked away in his collar.

All these scares, and there were certainly others, may seem a trifle far-fetched to-day, but one needs to keep perspective. The war was then a baby war; it had not yet grown into the monster of calculated craft and horror it was afterwards destined to become . . . we were all so many Frankensteins in those days steadily, secretly, diabolically piecing the monster together.

As operations developed, spring after spring, autumn after autumn, the old scares died away for new ones to arise in their stead.

First and foremost of these was the aeroplane scare.

As a communicating link between the opposing lines, the aeroplane had obvious advantages. Supposing, for instance, the British General Staff desired some information speedily from behind the German front in Belgium. To send an agent round by Holland and so into Belgium, and then for the man to return to British G.H.Q. by the same route took at the least twelve days. The aeroplane presented a ready alternative- drop your spy in Belgium and collect him again a few hours or days later by arrangement. Special pilots were selected for this delicate mission of spy-dropping, the agents dropped being usually Belgians. A friend who was present one might at the start of such a trip related afterwards that all through dinner the spy who was to be dropped, a young Belgian clerk, shook and shivered. About nine p.m. he was conducted out towards the waiting aeroplane. On seeing it, he shouted: "No I can't, I can't!" and headed away off the aerodrome at full speed. Others had more pluck.

The French - always imaginative - once dropped a pretty dancing-girl at a point not far from Brussels. The girl, who came from Luxembourg and knew German fluently and without accent, was commissioned to proceed into Brussels and there live a gay night life with German officers for a week or so - after which she was to proceed back to the point where she had been dropped and there await "collection." As events turned out, one fears mam'zelle must have liked the night life, or else met somebody she liked better than herself, for she never materialized at the appointed "collection" rendezvous, and the pilot, after waiting for several hours, had to fly off without her. Heated discussions would develop in the Flying Corps as to the status of a pilot if caught by the enemy on such a flight. Would he be treated as a spy and shot.

The spiritless Hague Convention offered no clue. It was ultimately reasoned out as follows : If the Germans captured a pilot and his passenger, and the latter wa~ attired in civilian clothes, the enemy had a right to shoot both. If the passenger was not dressed in civilian clothes, neither could be treated as spies. So thereafter all spies carried over the lines to be dropped wore uniform and changed into civilian clothes on landing. The usual plan would be for the pilot and his passenger to fly off late at night and make for some rendezvous prearranged with a resident agent in Belgium. Usually the alighting point selected would be some dark and deserted field, and in order to guide the night ifiers, the resident agent would flash a powerful light up his chimney - a light that no one could see save an aviator. The pilot, who would be flying at a great height, would then switch off his engine and glide down to earth-an essential being that his engine should be heard as little as possible. The passenger then alighted and changed his clothes in the resident agent's cottage, the pilot meanwhile flying off home. Most of the agents dropped in this style - there were not many - were what I have previously designated as "letter-boxes." That is to say they made a swift round of resident agents, heard what information these had managed to collect latterly, committed it preferably all to memory, and then were picked up again by aeroplane perhaps three days later and borne back to British General Headquarters, there to make a detailed report on all they had heard. Some of these air spies were caught-at least they never returned to their picking-up rendezvous. Usually the Germans, with the aid of microphones, heard the aeroplane engine humming in the stillness of the night, then heard the motor being shut off for the glide to earth, then re-start!ng with a roar as the pilot flew away home. A cordon would be put round the slip of territory suspected, and next day followed a systematic search of the whole area and cross-examination of the peasants. In the closing stages of the war the parachute was introduced into night spy-flying, spies being dropped by parachute from the aeroplane from a height of thousands of feet. This obviated in some measure detection of the engine by microphone.

Another method of retaining touch with an aerial agent dropped in Belgium was by the employment of pigeons. In this regard, many people are under the impression that a pigeon will fly home again to its loft from any selected point one chooses to release it.

Such is hardly the case The intricacies of pigeon flying are unknown to the present writer, but one believes it to be a fact, to quote a specific instance, that if a British spy arrived, say, at Ghent with a basket of pigeons taken from a loft in the British area at Boulogne, and if he proceeded to release these pigeons, each one with a message attached, the chances of their "homing" to Boulogne would be small Apart from which, the risk was always present of the enemy capturing these spy-pigeons and turning them to his own use. This very nearly happened once.

Shortly before the battle of the Somme opened, a spy-pilot flew off carrying a male agent, a Belgian, and a basket of pigeons. The plan was for the pilot to alight on the outskirts of a wood near Ghent, in answer to signals flashed up a chimney by one of our resident agents there, and for him to fly home again as soon as his passenger had been safely landed. The latter was then to collect his information and liberate his pigeons accordingly, with messages attached. Unfortunately on landing the pilot crashed and killed his passenger. The pilot himself was pinned under the wreckage with a broken leg, the basket of pigeons lay a yard or two away, out of reach; the Germans would arrive at any moment. Obviously the first thing they would do would be to take the pigeons to headquarters, whence they would presently be liberated with messages bearing false intelligence - the worst conceivable thing that could happen. The pilot grasped all this and started shouting. Happily he was heard by an old Belgian woman, who proceeded to release the pigeons. To one of them was attached a staccato version of the tale now related.

I have already said that the possibility of the Germans employing an undetected wireless apparatus in the field for purposes of communicating information across the lines diminished, literally vanished early on in the campaign. Nevertheless, there was always the chance that German Telefunken brains might steal a march on Marconi minds and suddenly evolve a system of wireless that defied detection. The closest and most systematic wireless vigil had therefore always to be sustained, night and day, month after month.

One heard a lot in this respect, of "secret wireless, during the war. Spies were supposed to be flitting about m large numbers collecting information and then sitting down, pulling out a secret pocket wireless instrument and transmitting what they had to say in code. All that was so much rubbish, however much it may pain the authors of sensational fiction. There is no such thing at present, as secret wireless. I remember discussing the point with Mr. Marconi, in Rome, in the spring of 1918. We were discussing wireless intelligence, i.e. the system by which we were overhearing what the German armies were sending, and I ventured to suggest that the whole military course of the war would have run differently if there had been such a thing as secret wireless; for one thing, we could have equipped our agents in Belgium with the secret installation and maintained uninterrupted communication with them. But the effect on operations in the field would have been even more pronounced. The wizard of wireless shook his head. "I know only too well the value of secret wireless," he said, "but we have not yet progressed far enough. I have been engaged on the problem, on and off, throughout the war."

Possibly the nearest approach to anything secret in the wireless line was continuous wave, with frequently altered wave lengths during transmission so that an enemy experienced much difficulty in "catching" you and tuning up and down to you-in fact, with any luck, he missed half you sent. A comprehensive system of wireless police stations existed on the French and British fronts for the detection of any station sending illicitly. The Germans had a similar protective system in operation. Broadly speaking, this protective system was organised as follows: each Army (of seven or eight Divisions) had attached to it several intercepting stations and so called "compass" stations. This joint grouping of stations fulfilled the double mission of overhearing and locating all the German army wireless stations-and there were hundreds of them sending every day-and of keeping a constant look-out for any wireless being used by spies behind the British lines. Night and day the vigil never ceased. The operators on the intercepting stations took down everything they could hear; the operators on the compass stations located by magnetic intersection all transmitting stations. This locating apparatus, also known as a Direction Finder, was one of the great things developed in the war. With a direction finder, one can get a magnetic bearing on any station, either still or motionary, transmitting wireless rays. That is to say, we have two compass stations, one at London and one at Paris. A German station, anywhere, suddenly starts sending wireless. The London compass station gets a bearing of, say, ninety degrees on that German wireless, the Paris station a bearing of fifty degrees. Where these two bearings from London and Paris intersect, there is your German station. The value of this apparatus in detecting illicit war wireless is self-evident; it made secret sending absolutely and finally impossible. If a German spy suddenly started sending wireless from a lonely spot in the rear of the British near Ypres, the compass stations detailed for that area would at once turn upon him and intersect his approximate position to a mile or two. That there were many scares is true, but during four years in France and Italy and Palestine and Macedonia and Mesopotamia, the writer only heard of one secret or "spy " wireless scare coming to anything.

This concerned the great German transmitting station at Nauen which, in between its propaganda (sent in clear), would be responsible for an alarming medley of apparent rubbish put into the ether at lightning speed. At first it was thought that this jibberish was merely a clumsy attempt at janiming our sending stations. But German wire-less brams were not at any time known to us as clumsy, and so one or two young officers selected to spend much of their spare time, and even their leave (for the keenness of a wireless expert is entirely unique) in trying to "solve Naue”.

It had, of course, long been a practise to record enemy wireless messages, while they were being sent, on an ordinary gramophone cylinder-which could be turned on at any time subsequently for our decoding experts to stand by and listen to. It was in this way that the Nauen mystery was ultimately solved. One day while an officer was amusing himself playing a record of Nauen's "lightning jibberish," as sent out by the enemy the previous day, the gramophone spring ran down and as the record revolved slower and still more slowly-that lightning jibberish gradually emerged as a perfectly good code. In effect, as our code experts soon found out, it referred to the activities of German agents in Spain and in South America.

Everyone knows that other service rendered by the direction finding apparatus - the location of Zeppelins - as the result of which our pilots would be dispatched to attack the gasbags in a given area out at sea. The Zeppelins used less and less wireless towards the end, but whenever they lost their course they had to resort to asking Cuxhaven and Tondern for their bearings. A Zeppelin operator would transmit his code call - XY and then a sequence of V's or any other group of letters. The compass stations at Cuxhaven and Tondern would get magnetic bearings on the good ship XYZ, an intersection on it, in fact, as it sent its "V's," and then a transmitting station would proceed to wire-less these bearings in code to the airship, whose commander would thereupon plot his position at that moment over the North Sea. After which, he would alter course or sail straight ahead on London as the case might be.

The Germans of course knew we picked up all their messages and that we were able to plot the position of the good ship XYZ as accurately as they themselves could do, and so the resorted to subterfuge, such as sending out la se ear 5, etc. . . . But we are getting into deep water, almost as deep as that into which the XYZ and her sisters sank....

A lasting memory of all this Zeppelin wireless was that of a visit to a room on the fourth floor of the War office while a raid was in progress.

The latest bearings taken by our own compass stations on the XYZ would be shot down by automatic tube from a station on the roof. Casually, cigarette in mouth, an officer plotted them.

"Old Mathy's twenty miles south of the Dogger Bank," he would say and, then, as casually, go on chatting about theatres or leave or anything topical.

And then - it was early afternoon - we wandered out into the West End knowing that a raid was to begin in a few hours, and sauntered along well-known streets teeming with women and children, ignorant of it all, planning outings for that very evening, submerged in darkness and composure, a strange sensation that, an effort and a big one, to keep silent.

But I am wandering far from the mud of Flanders and communication by spies across the line.

One of the prettiest romances of the war hinges on the existence of a wireless station on Belgian territory at Baer-le-Duc. Baer-le-Duc is a little patch of Belgium overlooked at the Peace Conference of 1839 and left, surrounded by Holland. It is as if a Scottish town had been left in England two or three miles south of the Border. Baer-le-Duc lies on the railway from Tournhout (Belgium) to Tilburg (Holland) and may count, in all, four hundred inhabitants, Belgians. Directly war broke out, its value became obvious. It was nothing else than a strip of Allied territory in the rear of the German armies, but unassailable by those armies in that it was surrounded by neutral Holland. Although the German guards posted on the Dutch frontier could actually look down the main street of this little Belgian village, they could not touch as much as a hair on the head of any one of its inhabitants. And the Belgians profited to the full by the fact. They made of Baer- le-Duc a rallying centre for escaping French and British, and they allowed the latter to erect a wireless station in their midst. This wireless station for a long time transmitted coded information daily to the Allies. The Germans not only knew the station was there; they could actually see it.

They placed an intercepting station on the frontier, opposite to it, and everything the Baer-le-Duc station sent, the German station promptly intercepted. But it was always in code, and by the time the Germans had solved one code another was already in use. Certain Allied agents, after spying on the Germans in Belgium, would head straight for Baer-le-Duc on crossing the Dutch frontier clandestinely, and there get such information as they had assembled carefully encoded prior to having it despached by wireless. But, unfortunately, difficulties soon arose in connection with the working of the station. A wireless installation of this power requires large quantities of petrol, and after a time the Germans formally protested to Holland against supplies of petrol being admitted into Baer-le-Duc as it was being used there for a warlike purpose.

The Dutch of course readily agreed not to let any more supplies through, and then began a long-drawn-out and perilous process of petrol smuggling into the brave little Belgian village. The principal smugglers employed were fat old Dutch and Belgian women who would hide a gallon or two of petrol under their skirts - one or two made little difference to their natural contour-and so cross into Baer-le-Duc. A greater difficulty was, however, to follow. The Germans succeeded in corrupting some of those employed at the transmitting station, and on several occasions false information was wirelessed across to the Allies in France. This was the worst thing that could possibly supervene, and one fears that in the closing months of the war the romantic wireless of Baer-le-Duc was of little practical value, since its contents were looked upon by the French and British General Staffs as strongly tainted. But earlier on, it nobly served its purpose.

One more wireless tale and then silence.

During the first battle of Ypres, when the British were taking up a new line from day to day, communication between the fighting area and G.H.Q. behind could only be sustained by dispatch riders and by wireless.

Dispatch riders repeatedly became casualties while bearing their messages, sometimes with dire result for whole units, and so, one vital night, when a fam6us General desired to communicate the latest disposition of his forces to Sir John French, he ordered his bulletin to be transmitted by wireless.

The wireless officer refused to send the message off.

The message was in clear - no code or cipher pre-arrangement had been made in the flurry of events-and it gave precise details of the whole British order of battle. The Germans would certainly pick it up.

"Tell that young man," said the General, on being informed of the signal officer's attitude, "to begin to send that message off within the next five minutes."

The signal officer now had to comply, and details of the whole British situation round Menin were put "into the air" for the benefit of friend and foe alike.

And then a remarkable thing transpired.

The Germans intercepted the British message right enough, came to the conclusion that no commander in his senses could be guilty of sending such information in clear about his troops, were it the truth, decided therefore that the message was a hoax and made fresh dispositions accordingly.

"I knew they'd come to that conclusion," later proclaimed the man who caused the message to be sent, "that's why I insisted on the message going off."

Well, well, given that our General was then, as always, strictly adhering to the truth . . . it was rather a risk, wasn't it ? . .

Looking back on the gradual development of espionage close up behind the line, one hazards the opinion that future intercommunication between agents in the field and their headquarters rests with the aeroplane and with wireless-an aeroplane mounted with a silent engine, and really secret wireless. That these two developments of engineering science will one day be accomplished facts admits of little doubt.

Then it will be possible for a Staff officer, say at Amiens, to instruct an agent: "go to Brussels and report every midday for a week what troops you see there." The agent is dropped silently m the night, strolls round Brussels for a week, and at noon every day duly wirelesses off his information.

There is one other potential development in espionage which needs to be borne steadily in mind.

The super-spy system is built up patiently in the dull decades of peace. A thorough people like our late enemies are quite capable of getting agents enlisted now in the British and Allied armies, and paying them year after year steadily for doing nothing . . . till the next war should break out. The soldier traitor was not wholly unknown in this campaign ; in any future "man-in-the-street" war such as this has been, he may be a deadly-enough peril. As an instance in point, in March, 1916, one of the first Fokker monoplanes ever built was flown down into the British lines at Merville by a German N.C.O. pilot in British pay. The Fokker W&B at that time universally dreaded, and the coup was worth twenty times the money - £5O I believe actually paid over to the renegade pilot.

There were other strange happenings in the air.

There were tales of Allied officers said to have descended in the German lines, visited friends, and then flown back home again with the enemy's kind permission. One does not wish to labour this side unduly, but it is manifestly clear that no spy is better placed than in the Flying Corps of the country he is spying on. What is simpler than for such a man, flying from day to day on active service, to note everything going on around him and then, while on patrol, to drop his information at a given point in the enemy's lines and with a smoke fuse attached to guide those searching for the package below? And more extravagant things could happen, in espionage, than that a soldier spy in enemy pay, a gunner, should secrete information in a special "dud" shell before dispatching it, perhaps a distance of ten or twenty or thirty miles into the very heart of the enemy's territory.

I have dealt in the foregoing with espionage intercommunication close up behind the lines.

Very different circumstances attended inter-communication between spies working far away from the battle line, in the big cities and ports of England, in neutral and belligerent lands, and on the high seas. Dogs and windmills and pigeons were replaced, now, by invisible inks and newspaper codes and other strange tricks of the trade.

In popular theory a spy, of course, had things all his own way. In fur coat and high- powered car, he just motored down to some secluded spot on the coast and there lamp-morsed out to sea a resumé of the latest gossip he had heard that very evening at the Carlton. Or else, there arose the terrifying bogey of an old gentleman of Teuton ancestry, seated in dressing gown, skull-cap, and bedroom slippers, flashing signals- heaven knows what - up the clumney of his house to a Zeppelin poised overhead. Or else there was the letter found on the prisoner on arrest, and positively dripping with invisible ink . . or again, the wondrous siren, a guest on board H.M.S. Bimbo, rushing into the captain's cabin, seizing the "irreplaceable" code book and dropping it overboard to her lover, Fritz Von Bosch, comfortably supported below on swimming wings. One recalls too the secret wireless in the church tower which was worked by someone playing the organ below, and the man-killing widow, with pigeons artistically concealed in her corsage, and cooing with keenness to be released.

Verily, the spies had it all their own way.

In point of fact, "communications" were much less spectacular.

Take one of the most dangerous spies ever caught in Italy. The agent in question, a commercial traveller representing a Milan business house, journeyed continuously between Milan and Taranto, the naval base at the toe of Italy. Arrived at the latter place, and thoroughly camouflaged as an honest business man bent on his own work, this spy in the pay of Austria would go and sit in a little back street cafe' and there drink vermouth or malaga with friends of his employed in the docks. These men (by word of mouth) conveyed the latest they had learnt to the commercial traveller, who would then proceed back to Milan, always unsuspected, and convey the information thus gained, still by word of mouth, to a Swiss whose business took him frequently from Berne to Milan, and vice versa.

Once arrived back in neutral Switzerland from such a trip, our Swiss would at last commit the Taranto information to writing and hand it over to one of a dozen "receiving agents" retained by Germany in Switzerland throughout the war. Within a day or two the full report lay on the tables of the Naval General Staff at Cuxhaven or Pola. That is the prosaic, utterly unspectacular way in which this successful agent worked for many months. Such agents of transmission were exceedingly hard to apprehend and practically impossible to convict. The system generally followed in tracking down these "honest business men" was to watch their expenditure or banking in relation to their known salaries, and to note whom they consorted with on their journeyings. Should such enquiries give rise to suspicion then the delinquent would be refused a permit to travel next time he applied for one. Little else could be done in the absence of proof positive of complicity with the enemy. Thousands of people must have been in this way prohibited from travelling, merely on suspicion, though perhaps only ten of those thousands were enemy agents.

Almost as difficult to track down was the man who wrote perfectly harmless looking business letters to a neutral country, each word and sentence and the manner of turning a phrase conveying a specific meaning to those there to decode it at the other end.

Then there was the possibility of a war correspondent acting as an agent of transmission to the opposing army.

It would be no difficult matter for a war correspondent, were he an agent, to communicate intelligence to the other side by employing certain sentences and words in his cabled despatches. Thus, the phrase, "The Russians fought splendidly," might easily be the code for "The Russians are running out of heavy ammunition." This method of communication had the added merit of being immediate and authenticated.

A typical example of the "innocent letter" form of communication was unearthed in connection with two German women, a mother and daughter, living at Hampstead. These two women, who were sentenced to long terms of imprisonment, would report on the results of each Zeppelin raid by indulging in enthusiastic accounts of bird life locally. Eventually the censorship authorities came to the legitimate conclusion that bird life at Hampstead could hardly be of absorbing interest to people living in Holland, whither the letters were addressed, and a comparison of the letters with subsequent raids led to this perfectly legitimate conclusion crystallizing into suspicion and later, into certainty, that the women were spies.

In this respect, many people wonder what assistance a precise knowledge of where his bombs drop can be to an aerial enemy. This after-knowledge is of the same assistance to him as an observer "spotting" artillery fire, is to a battery. It corrects him and directs his future bombing accordingly.

At 10.12 p.m. a bomb dropped on the Lyceum Theatre," reports the German spy.

The airship commander turns to the chart of his progress over London on that particular raid and upon which the time each bomb was released is duly marked in.

"At 10.12. I thought I was over St. Paul's," he says, "it seems I was half a mile further west." Which error would be duly noted for the next raid.

The submarine was a distinctly valuable asset to the enemy's secret service, both for landing spies in England, and even in France, and for collecting reports from agents resident in the big ports like Cherbourg and Liverpool. It is doubtful if lamp signalling from the shore out to sea was practiced to any great extent. However, in the case of a certain lighthouse keeper, it was indicated that the man, who lived in the lighthouse with his wife, habitually supplied oil to German submarines and also reported to the enemy the vessels he had seen passing that day, their names, size and speed. To entrap him, the obvious was done. Once suspicion had been aroused, a watch was kept and the precise nature of the signalling from the lighthouse carefully noted down - especially the signal stating that oil was ready to hand if the U-boat would land a pay for it. And then, one night, a party of marines stood by on shore and when the oil signal was duly sent out, quietly took the Germans " in charge as they landed on the beach. This case, however, was an exception.

The course usually followed by spies wishing to communicate with submarines was simple enough. The information wanted by a U-boat commander concerned the date, time and nature of sailing from such ports as Liverpool and Glasgow, so that he could lie outside and torpedo the ships as they passed. In a big seaport town there is always a large foreign colony, Danes, Spaniards and the rest, connected with shipping firms and business houses, and it was from this foreign colony that the Germans recruited their agents for U-boat espionage work. Such an agent, living continuously in dock- land, would assemble his information and then bicycle out to one of several rendezvous points on the coast and there hand over his report to a collapsible boat party from the U-boat. There is little doubt that this system was practiced successfully and that the knowledge the Germans thus obtained of British shipping sailings contributed to the serious sinkings that ensued. Losses, however, fell away towards the end thanks to the inception at all British ports of a "false report " system such as I have outlined in a preceding chapter and as the result of which, no one save those very much "in the know " knew exactly which ships were sailing, and when.

As a method of passing on information, neutral courier bags being borne by special messenger from London to Holland and Scandinavia were looked upon with longing eyes by enemy agents. These bags would be sealed up at an Embassy or a Legation in London and then committed to the care of a courier who would hand them over, unopened and untouched, at the Hague, or at Stockholm or Berne. The belligerent powers had no right of examination of the contents of these bags; implicit trust had to be placed in the integrity of the neutral Embassy staffs dispatching them. It is said that when the risks attaching to this system became too glaring to be further ignored, each neutral ambassador or minister was invited to arrange that no private letter or document of any kind should henceforward be enclosed in an official bag. The efficacy of this "invitation" was emphasised by the arrest, quite late in the war, of a pretty Scandinavian girl who had for some considerable time made use of an official bag, passing to and from a neutral country, for purposes of espionage.

This young lady, who is now undergoing a sentence of penal servitude for life, was one of those rarities-a character of stereotyped "spy" melodrama emerging in real life. She collected her own information in her own way, and she arranged for its transmission to the proper quarter. Nobody helped her; it is not believed that anybody ever paid her. She came over to England to learn English and to stay with friends. That was in 1916. Besides good looks - "a fair, sparkling, slip of a girl" she could amuse and interest and dance and play the piano, and people, quite nice people, sought her company. The story runs on accepted lines. Flirtations were the order of the day; occasional war-time romances with officers home on leave, and with others liable to be of service to her, were not ruled out. The Scandinavian girl learnt a lot in her quite smart, if not ultra- fashionable circle, and, still radiating her seductive charm, obtained permission to correspond with friends at home via a neutral courier bag.

"It is so much quicker and more dependable." Her career was terminated, but only after many months, by information being laid at Scotland Yard by someone who happened to know the contents of each official bag dispatched from the Legation in question.

Another system of communication relied on by spies, probably far more than the authorities ever suspected, was that of women giving letters to officers returning to the front, for posting in a country other than that in which the spy was her-self resident at the time. This had obvious advantages. Let us suppose a woman in London, not necessarily herself an agent, but in touch with a resident London spy and anxious to serve enemy interests, asks an officer returning to France to take a letter with him and post it "at Boulogne, or Amiens, or Paris, or anywhere." The letter bears a Paris address. The officer agrees and posts the letter in Paris. And so, bearing the local postmark, and being so innocent in character, the chances are a hundred to one against its being suspected by the Paris censorship. It is duly received by the addressee, a resident enemy agent in Paris, who proceeds to decode it and forward the contents, after one of his own particular systems, through to Switzerland. The woman in London has done nothing else than defeat the British censorship. Had that letter been posted in London it would probably have been photographed, ified and tested for invisible ink.

It is a strange thing that officers and men were never sufficiently warned against taking letters abroad in the manner described. Nor did officers stop short at carrying correspondence for ladies of whose integrity, to say the least, they could hardly be guarantors.

On one occasion, an affectionate British officer motored a German-American actress the whole way from Italy to Paris "just for a spree." At the frontier there were apparently no questions asked, miladi probably being thoroughly well wrapped up in a British warm. Only in Paris was it pointed out to the gentleman at the wheel that his fair companion had long been a suspect both in London and in Paris, and that the French had only been too pleased to pass her on, at her request, to Italy, but that they had resolutely opposed her efforts to get back into France and that the railway authorities had been specially warned to stop her retreading French soil. Hence the lady's innocent suggestion to her admirer that they should make a motor-car run of it right through from Italy to Paris. .

To descend from pretty ladies to lascar seamen. To make England spy-proof, we should have had to examine every seaman arriving from a neutral port, from the lining of his cap to the soles of his boots; especially the latter, a favourite place for concealing information. When one considers the thousands of lascars alone who put into port, the hopelessness of the project becomes clear. A vessel would be getting up steam, say at Hull, bound for Gothenburg. Customs officials and dock detectives would complete an exhaustive examination. Meanwhile the crew idled about. Presently one of their number sidled away behind some barrels or bales. There he would be handed an envelope . . . in half an hour the ship had sailed. It may be assumed that the more trustworthy and intelligent of a neutral ship's crew, such as the officers, stewards, etc., were sometimes employed to give verbal instructions to German spies in the big Allied ports and even to pay out money to such agents on behalf of those employing them. The peril of the seaman, as an agent of transmission, will always remain. It can only be lessened by good work ashore such as the arrest of consul Anlers and the German pastor at Sunderland, and, if necessary, by confining all neutral ship's crews to their vessels during their sojourn in port and by preventing unauthorised persons gaimug, contact with them-a big proposition.

Special Intelligence officers were detailed for duty at the various ports to control all incoming and outgoing merchantmen traffic. An officer, for example, would be located at Cardiff mainly to control the Spanish traffic with Bilbao; another would be detailed to Newcastle there to check all Scandinavian sailings and arrivals. These officers, required, besides linguistic ability, a nimble and tenacious mind so that in the cross- examination of suspects which formed most of their work they might pounce on any rash statement or weak explanation. They also required to be past-masters in the art of bluffing. Thus, by bluff alone, a Spaniard was once made to confess that he had been given 17,000 pesetas to come over and spy in England.

How two German naval officers circumvented the British contre-espionage network by posing as cigar merchants, throws another ray of light on spying in war-time.

These gentlemen used an illustrated catalogue of cigars for their code, the five types of cigar shown - very large (battleship),large (battle cruiser), medium (cruiser and light cruiser), small (destroyer and torpedo boat), very small (submarine). The two spies separated and paid rounds of visits to the principal ports communicating as follows with their firm in Holland :

Harwich: Please send twelve hundred No.2 Havanas, six hundred No. 3 ditto, and two thousand half Coronas,

meaning:

There are now in harbour here twelve battle cruisers, six cruisers and light cruisers, and twenty submarines.

The two Germans owed their conviction and subsequent execution in some measure to their own carelessness. It would have been difficult to have made out a full case against them but that each told different tales when separately examined on arrest.

A system of secret communication which flourished at the outset of hostilities, and indeed well on into the war, concerned the insertion of advertisements in newspapers (as in the Muller case). The "agony', column of The Times had always to be closely scrutinised lest some seemingly harmless personal announcement should conceal a code. In one instance, an advertisement in The Times relative to the sale of a dog was found to conceal the information that a British Division was moving from Salonica to Egypt. A special branch of the censorship did nothing else but check all advertisements inserted in home and foreign newspapers.

A woman, who was afterwards shot at Toulon, was caught by a fairly obvious newspaper ruse. In many of the lighter Paris newspapers, such as the Vie Parisienne, appeared during the war a page of very personal requests by both officers and men, for marrainne - or godmothers. Objects: an exchange of correspondence; later, a meeting between the godmothered one and his benefactress.

A poilu's main object in linking up thus with an unknown and possibly unattractive woman, was the strictly business one of getting his marraine to send him gifts of food and even of money. Clearly here was a chance for the woman spy to step in.

By freely answering these "agonies" coming from the trenches, it would be possible to obtain sundry locations of units on the field, and later, in personal contact, to "pump" godchildren for details of their life at the front. The French contre-espionage - not usually slow in tumbling to espionage possibilities, did not prohibit marraine announcements until 1917. Possibly, before that, they were trying hard to entrap women spies and so allowed the advertisements to continue. They trapped one such, the lady of Toulon, by the simple stratagem of instructing one of their agents to pose as a poilu and advertise for, and correspond with, and afterwards meet, this particular would be. Under the skllled scrutiny of her godchild, and quite off her guard, the woman soon emerged in her true colours.

I have already mentioned the possibilities of wireless telegraphy and pigeons as mediums of espionage inter-communication across the lines. If pigeons and wireless were impracticable over short distances, one may safely set them aside as doubly so in the case of communication over the wider areas. Precautions taken against such a leakage were thorough, and were the same in most of the countries at war, viz. registration of courier and homing pigeons; civilian wireless illegal. Similarly, the restrictions on cables were such, after a very short while, that spies avoided using them as they would have avoided the plague.

Some strange devices were resorted to in Belgium to defeat the German contre-- espionage authorities for ever searching civilians lest they should be bearers of information towards the Dutch frontier.

Not so long ago the writer stood amid the ruins of the great Ougreé Marihaye steel works of Liége. My guide, the works manager, explained that he had spent two years in a German prison on suspicion of having been a spy.

"And were you?”

The manager looked up at me a moment then answered: "Eh bien! perhaps they weren't so far out in their suspicions, those boches! For two years I reported everything that happened in Liége to the Belgian military headquarters at Havre. I used to conceal my reports, between here and the Dutch frontier, by placing them round the exhaust pipe of my motor and then covering them over with a winding of felt."

Belgian spies concealed their reports in bread and other articles of food; they even, in an emergency, swallowed incriminating pieces of paper. The nature of the German frontier search of each individual, man, woman and child, made it practically impossible to conceal documents on the person. That the heavy Teuton was, however, systematically hoodwinked goes without saying.

Quite the most interesting spy exhibit one remembers having seen is a copy of the Etoile Belge, dated the end of August, 1914, and now in the War Office museum. It is all covered in grease as if butter had been rolled in it, and the whole centre of it is burned away. It arrived wrapped round a pair of boots carried by a Belgian refugee into England in the first weeks of the war. Written in invisible lemon-formalin ink across all its grease, and carefully leaving off where the burned hole began and continuing where it ended, is a complete record of all the German troop trains, with complement, that passed through Liége up to August 22nd, 1914. Its heroic compiler had lain day after day hidden in a culvert by the side of the line, noting Iris observations. His information, conveyed directly to General French, then retreating from Mons, was of the highest possible value.

Another striking exhibit consists of a photographic enlargement of a map of Amsterdam. Its original, the size of a postcard, was sent through the post in a letter. Almost indecipherable, along the tramway routes marked on the map are rows of Morse dots and dashes. These when brought out in the photograph revealed a coded message which gave the identity of a dangerous spy and enabled the authorities to lay their hands upon him.

The Germans were very fond of using invisible ink. Many of their spies caught in England, such as the suicide Kupferie, and Ernst and "Eva," were entrapped by the vigilance of our chemical experts, while it is likely that many more enemy agents who, escaping detection, are still with us to-day their mission temporarily o'er, had the excellence of the German invisible ink industry to thank for their good luck, rather than their own cunning.

One must bow in admiration before the method adopted by the Germans in introducing new brands of invisible ink into England for the use of their agents. Over in Germany, at the Intelligence chemical laboratory, they would soak odd garments, such as vests and pants, in certain mixtures. The garments thus treated would then be innocently conveyed over to England in the valise of a neutral business man travelling freely across the North Sea. In England, the vests and pants would be handed over to a resident agent who, by a simple chemical process, would extract from them the newest and latest brand of German invisible ink. The British authorities actually detected this ruse by testing a pair of old socks, taken off a suspect. They were found to contain the necessary ingredient for an, as then, unknown new ink. After that the danger became so pronounced that a special analytical laboratory had to be established m London for testing the clothes and intimate belongings of all suspects arriving from the continent.