from ‘the War Illustrated’ 1st September, 1917

The Army's Monster Mail

- By Basil Clarke

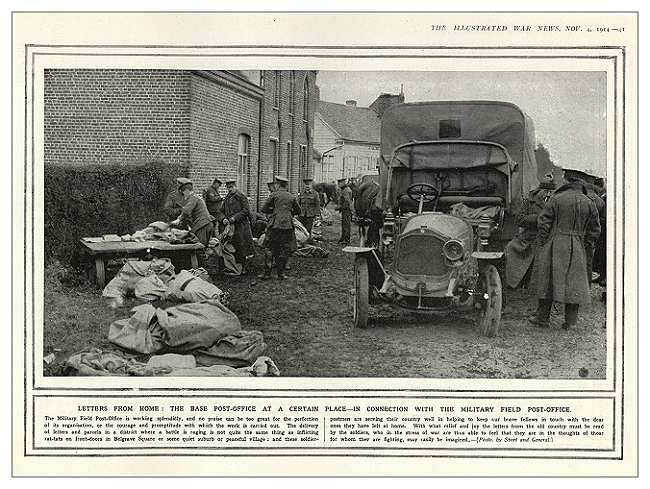

from a British magazine 'the Illustrated War News'

How Letters Reach Our Soldiers in the Field

The soldier without his letters from home is less good a soldier.

So thoroughly has this been proved in wars, both ancient and modern, that it is now a military axiom ; and the Army Postal Service is included in Field Service Regulations (Part II) as one of the departments, of the Army without which the fighting troops cannot "be maintained in a state of efficiency."

Letters from home are as essential in their way to a soldier in the field as food and supplies; for just as food is needed to keep him in fighting trim so is news of relatives and friends to keep him in good spirits and in fighting mood. It is evidence of the importance attached to the postal service in the war that more than 4,000 men are occupied in the Army Postal Service, dealing exclusively with letters and parcels for soldiers. They handle no fewer than twelve million letters a week and not far short of a million parcels. Those letters, if stacked one above another in a pile, would be about twenty miles high.

Apart from the handling of letters immediately after they are posted in local post-offices, the whole of the work of carrying them to the armies in the field is done by the Army postmen. These men are a special section of the Royal Engineers. They have their own colonels and other commissioned officers and non-commissioned ranks, representing all grades of the civilian postal service. Nearly all the men, in fact, were postal servants in civil life and now carry on in khaki for the Army the work they did for civilians in years gone by.

"Initial" Difficulties

The Expeditionary Forces have their own post-office in London — an immense place quite separate from the ordinary post-office, and staffed by many hundreds of men. To this office are sent from all parts of the country all letters bearing the magic address B.E-F. Every post-office of any size has its special B.E.F. bag or bags for London ; and all hours of the day and night trains are arriving in London with their loads of B.E.F. bags for our soldiers in the field in France, Egypt, Greece, or elsewhere.

In London the great work of sorting begins. Sorters in khaki, standing before shelves of innumerable pigeon-holes, are now experts in numbers and initials where formerly they dealt in names of towns and streets.

The soldier's habit of putting merely the number and initials of his unit on the top of his letters home has led to the very general adoption of this practice on the part of people answering the letters, and the Army weakness for initialing things, people, and units is seen at its height on the letters reaching the London sorting office.

All the regiments must "be known by their initials to the sorter. All the different ranks and appointments, some of which are expressible only in seven or eight initials, he must have at his finger ends. Thus "A.D.A.D.A.M.S." Stands for "Acting. Deputy.. Assistant Director of Army Medical Service" ; "M.T. 50. Sub. Am. P.. AH.B.5." means, "Motor Transport, 50. Sub Ammunition Part, Attached Heavy Battery Section."

When you consider the thousands of queer duties held by men in so huge an Army, and remember that each duty may be expressed in initials, you can realise the enormous task before, letter sorters. One sorter the other day racked his brain for several minutes over a tetter addressed to a private, "Care of O.C.P." It was not till he had examined the key list that he discovered its meaning : "Officer Commanding Pigeons."

Postal Base in France

From London the letters, daily sorted into units and stationary post-offices, are despatched to the postal bases of our different Expeditionary Forces in the field. Those to France, where the greatest proportion of the mail goes are landed at the main postal base, the port of ———. A few other bags of mails addressed to G.H.O. and different Army headquarters may go to other ports, but the great bulk of letters to the Army go to ——— which though not the principal base in France, is nevertheless the principal one so far as the postal service is concerned.

From the central post-office all letters not for local distribution or for special distribution are forwarded to points in the field by rail. They go in the "supply trains" which travel every day with one day's rations to different "railheads." Each division in the field draws its supplies day by day from a "railhead," and with the motor transport column that goes to fetch these supplies are included special motor-lorries for the carrying of mails. These lorries have a small postal staff attached to them, as have also the special postal waggons of the "supply trains" that travel up from the base. The letters thus never leave the charge of Army postmen. Earlier in the war the Army Postal Service control of mails ceased at the "railhead," and men of the divisional .supply columns (Army Service Corps) then became responsible for them. This proved to be a success,

On the Way to the Front

Nowadays the postal lorries of the Motor Transport supply column run through with mails right from "rail-head" to "refilling" point — a point some little distance behind the front lines to which every unit sends its own horse transport for supplies and mails. There is a post-office here, a big affair, and while some waggons of the horse "trains are filling up with food and supplies others go off to the post-office and collect sacks of mails for their units.

Up they go towards the front lines, and are delivered at the field post-offices. To picture a field post-office, shut out all ideas of what a post-office may be like. The only sure way to recognise a field post-office when you see one is by the little oblong flag, half white, half red, that flies over it. The post-office may be a barn, sadly knocked about by shell, with holes in wall or roof, or both. It may be a little bell tent in a corner of a field and the postman, when you call may be melting his sealing wax for out-going mailbags over a fire of broken boxes or smashed-up furniture. Or it may be a dug-out, or a cellar deep down under the earth.

I spent half an hour in a dug-out post-office once in the valley of the Somme. You climbed down to it by twenty muddy steps made of plants. A stove chimney-pipe ran to the upper air by way of the strips, and in feeling your way down in the dark you invariably touched the stove-pipe and burnt your fingers. At the bottom the place looked more like some pirates' or smugglers’ den than a post-office.

A sergeant postman was in charge and along with him were two corporals as assistant postmasters. They were opening the mail bags, newly arrived and before long were sorting the letters into companies and platoons. Soon fatigue parties and orderlies from the units in the line began to come down for their letters, and each man took back a little wad for his own unit.

The scene, all enacted by the light of two candles and a smoky paraffin lamp amid narrow walls of clay supported by timber balks was singularly picturesque. The sound of the guns and dropping shells not far away lent a curious unreality to it all. To see a soldier in shirt-sleeves, struggling patiently to read a badly-written name and address while guns were booming not many yards, away, was unlike any preconceived notion of a post-office.

A Hint to Friends at Home

It was in trenches and dug-outs of the front lines that one saw the consummation of all the splendid work done to assure our men getting their letters. As the orderly arrived from the post office it seemed as though letters were more important than food, tobacco, ammunition, or anything else.

Men swarmed round him bubbling with eagerness. "Anything for me, Puggy ?" "Anything for me ?" the shout came from all sides and the orderly carrying the letters had to stave off hands which would have seized his pile of letters had they only been able. "Now wait a minute, all of yer, and I'll tell yer'."

He climbed on a hummock of clay and sat down. Then, slipping the string off his bundle of letters, he picked them as one by one, shouting the names of the addressees.

It went something like this : "Hubert Smith"; he looked up and threw the letter towards a hand eagerly extended for it. "Will Jones, Charles Pearce, Hubert Smith (you must owe money, Hubert!), Henry Hall, Bert Morris, Hubert Smith (how she must love yer '), Henry James," and so on right to the end of his pile.

The joy of the receivers of letters was only equalled by the glumness of those who had received none. Some grumbled openly : "Five brothers, three sisters, twenty-two cousins, and not one of them written.” Others said nothing, but returned sadly to their tasks. And if friends at home only realised how sadly, they would not omit to write to their soldiers.