to an original Great War color photo of a French 75 mm piece

A GREAT GUN

by D.Cambranis

The Famous "75”

When, a few years ago, the Greek army decided to adopt a new field gun, several of the best firms in the world were asked to submit samples. The trial was to be of a very severe kind and on a great scale. The guns were to be tested from every point of view; accuracy of fire, resistance, handling. They were to fire a large number of rounds, then accomplish a long journey over different kinds of ground, roads, mountains, and ploughed fields, and fire again more rounds after the conclusion of the journey. In addition, they were to be tested by being hurled down precipices, and put into water and of course to be fired again after each trial.

Krupp a Cropper

Among other firms, Krupp and Schneider-Canné sent their field guns, the latter the now famous "75," called so, as everybody knows, from the diameter of its bore, which is 75 millimetres - about 3 inches. The test started, and very soon Krupp's began to break down. Its representatives protested, declaring that there had been some mistake when shipping the gun from the works. They were allowed to bring a new gun, and the test was resumed. But again the gun broke down, and the "75 " was declared to be the most perfect field gun. It had gone through the severest test without practically a single accident, and at the end of it was as sound as at the beginning. Krupp protested against the report of the Committee, and threatened the Greek 'Government with a libel action. Even the Kaiser himself interfered. But the Committee stood by its decision, and the Greek army adopted the "75."

The Devil's Gun

The result was that during the last Balkan War the Greek artillery at once gained a superiority over the Turkish, which was armed with Krupps. The Turkish soldiers who had to face that deadly weapon named it "the Devil's Gun," and in the present struggle the German soldiers have again and again confirmed the experience gained by the Turks. In letters and inter-views many have acknowledged the high efficiency and deadly results of the French artillery fire. Here is a statement by one of them:

Then began an infernal Sabbath. The French battery covered us with explosive shells. It was terrible. Shot followed shot with mathematical precision, and in the midst of that shrapnel and rifle fire it was like hell let loose.

The Perfect Gun

Many are the causes that make the French gun so efficient. Of course, a good deal is due to the perfect training and the scientific skill of the French artillery-men, but undoubtedly it is a question of a good tool in the hands of skilful workmen. The smallest detail of its construction has been thoroughly studied, so that it combines simplicity, strength, and durability; and the psychology of the man to serve it has also been taken into consideration. The intricacies of aiming, charging, and firing, which have to be performed under trying conditions, are simplified, so that mistakes are rendered practically impossible.

To illustrate this, I give as an example the regulation of the shells. As is known, the "75" usually fires shrapnel. Shrapnel is a shell which bursts automatically in the air at a distance regulated by the artillery-man. Each shell has to be regulated according to the required distance. This regulation is done by turning a ring containing the fuse, and on which are engraved the distances.

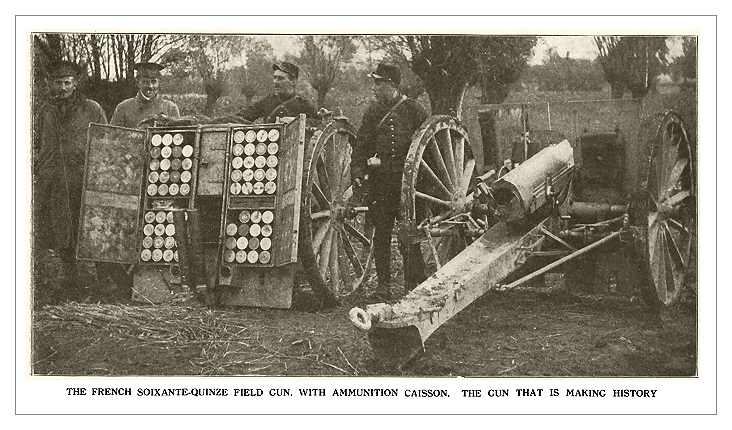

The Imperfect Gunner

But if man can make a perfect gun, he cannot invent a perfect gunner. By practice it has been found that even at manoeuvres the gunner whose duty it is to regulate the shells gets so excited and flurried that either he forgets to regulate the shells at all or else generally commits such errors that they do not explode at the required distance. In the "75" this error, which naturally would have been more frequent on the battlefield in the excitement of action, is avoided by an ingenious mechanism which is fixed on the caisson (limber), and which automatically regulates the shells after it has itself been regulated. The officer in charge of the gun can easily control this mechanism and see whether the shells are well regulated or not. This mechanism has also the property of regulating the height from the ground at which the shells must explode, and to render errors of that kind more rare, the doors of the caisson cannot be closed unless that apparatus is arranged to regulate shells at the average height required.

Manning the Gun

A French officer said that the greatest feature of the gun is in the rapidity of its fire, which depends on the division of labour among the gunners, and especially on the mechanical properties of the gun. Five gunners serve the "75"; one is seated on the left of the breech, another on the right, one charges, another passes the shells, and the fifth gunner regulates the shells on the automatic machine described above as he takes them from the calsson.

The man on the left of the breech is the man who aims through a telescope; the telescope is fixed on the gun carriage, and can be turned to every direction, and has across the lenses a cross formed by two thin lines. When the object given to the gunner is seen in the middle of that cross all he has to do is to bring the barrel of the gun parallel to the telescope; this is done by means of two handles, one of which is on his side and the other on the other side.

Getting the Range

The battery may be hidden behind a hill or any other obstacle which prevents it from seeing the object on which it has to fire. The battery's observer alone can see the object; he calculates the probable line connecting the object and the battery and fixes between them a spot that can be seen from the battery. He also calculates or finds by a special apparatus the distance, and gives the gunners the elevation or angle. The gunners train the gun on that spot, in this way getting the required elevation. Then they fire. The observer, by seeing the point of explosion of the shell, corrects the aim by ordering alterations in the horizontal and vertical angles. When the shells explode at the point wanted, all the gunners have to do is to load and fire without aiming at all, the gun after the first shot remaining motionless, being kept in position by a spade affixed at the point of the trail, which the recoil drives into the ground. Of course, at every discharge the barrel recoils, gliding on a cradle, but is brought back into position by a compressed air brake.

A Shower of Shrapnel

The rapidity of the fire, of course, largely depends on the quickness of the gunners. The man on the right opens and closes the breech by a lever movement; the feeder thrusts in the shell, which is fixed on a brass cartridge containing the charge, and the gunner on the left has only to pull a small hammer, which fires the cartridge. As I have before said, everything has been carefully studied, and the breech cannot be opened unless the gun has been fired. This is to prevent any accidents in case the charge should be slow to ignite.

Good gunners will fire from twenty-five to thirty rounds a minute. Of course, no such rapidity can be continued for any length of time, as the ammunition would very soon be exhausted; but the advantage lies in the fact that when the range has been found an enemy can be shelled before he has time to seek cover.

A Moral Force

There are many more details concerning the superiority of the "75," especially in the way of rapidly sighting the gun at various positions with great ease, but these are of a very technical character. The wonderful results obtained by this gun are so obvious to the fighter that they constitute real moral support for the army that uses it and demoralise the enemy. I have myself felt it when, previous to attacking an enemy position, I heard its sharp bark and the gradually decreasing growl of its opponents.

from the cover page of a French newsmagazine 'J'ai Vu'