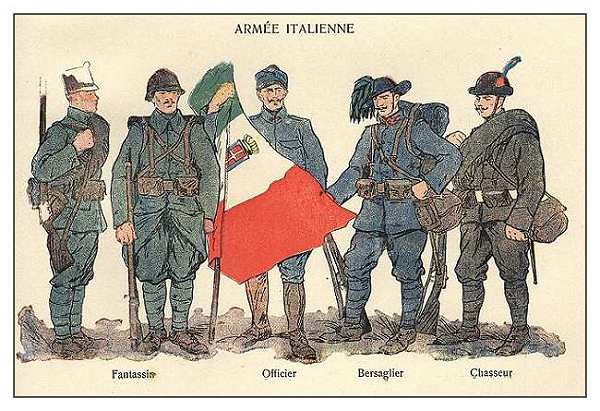

- from 'the War Illustrated' 16th June, 1917

- The Italian Soldier as I Know Him

- by Dr. James Murphy

- Special Correspondent on the Italian Front

Portraits of Our Allies

from a French magazine

When war broke out between Austria and Italy the fighting qualities of the Italian soldier were little known. Of dash and courage he had plenty, perhaps too much. That was recognised. But would he display the grit and endurance and capacity for detailed organisation which are necessary to success in modern warfare ? The German did not think so. He sneeringly called the Italian a mandolin-player. He knows better now. And he might have known from the beginning that there is a world of meaning in the contrast between beer and music. Had Fritz strummed "0 Sole Mi " beneath the window of his Gretchen, rather than shouted "Hoch Der Tag !" to the clatter of his beer-mugs, perhaps he would have been a better soldier, and Northern France would not be littered to-day with broken bottles and broken armies. Anyhow, the joke is now with the Italian side.

as seen by a French magazine - the new Italian brothers-in-arms

Spirit of Ancient Rome

And if we would be honest it must be admitted that the supreme prowess displayed along the circle of the Alps and on the stony wastes of the Carso came somewhat as a surprise even to friends and well-wishers of Italy. The truth is that though the world at large had supposed the Roman genius to be dead, it was only sleeping — sleeping and recuperating. Aroused from its centuries of slumber by the call of the Risorgimento it did. not become. fully awake until now.

In her sober moments Austria had realised that she would have to meet a well-organised and brave Army, but she probably never dreamt that she would find marshalled against her that genius for co-ordination and intense sense of solidarity which makes .each soldier feel the power of the mass concentrated in himself alone. It was this power which brought victory to the standards of ancient Rome ; and the modern Italian soon showed the Austrian that the blood of his sires did not course in degenerate channels.

Cadorna's Army is an Army of peasants fighting for the safety of their homes. Almost every experience which arrests your attention as you journey along the Italian line of battle is an illustration of that fact.

Devotion to Home

Though the soldiers have very few nicknames for the enemy or his weapons, they have names of endearment for their own. And these names are household words. Carlino — little Charlie — is the mountain gun which the Alpini employ ; the "75" is Lucia or Giulietta or Angelina, according to the favourite names in the family Bibles of the men who serve the batteries. To the soldier the armoured line which stretches from the Adige to the Adriatic is the wall which guards his home. Within it live his mother, sister, wife, his loved ones.

I suppose it is true that the men of every nation become children in the most critical moments of their lives, but I think this is truer in Italy than elsewhere. Wounded soldiers crying out in their agonies, generally call for their mothers ; they sometimes call on their God, and sometimes they curse their fate. In Italy I have scarcely ever heard any cry from the lips of an agonising soldier except "Mamma mia ! Mamma mia !" You hear if when they are being" brought in on the. stretchers. Home and mother seem to be the one idea running through the distraught brain.

A few of the soldiers' letters have found their way into print, and I think an example may give/the reader a glimpse into the minds of the men. who wrote or dictated them.

Renato Mazzuchelli writes to his family and friends : "I am now going to the field of battle, where flame and steel temper the lives of nations. I am going where there is no death, where only cowards and laggards die for. Though the body of the soldier may fall on the field, he lives on in the glory with which death has encircled his name. His friends and those who know him will speak of him to their children and say : ‘Forget not that name. It is the name of one who died fighting for the glory of our country.' I greet you, my country, my fair Italy. And you, my mother, fair and holy, you are the image in the shrine of my heart and the object of my everlasting thought."

This example, disclosing the soul of the peasant beneath the armour of the warrior, is typical of hundreds I might quote. But it must not be thought that the soldier whose mind is ever filled with poetic pictures of home and relatives envisages his task and its bearing on great world problems in a narrow outlook. Quite the contrary

as seen by a French magazine - the new Italian brothers-in-arms

.

A Brotherhood of Sacrifice

When you meet him and chat with him in trench or camp, you discover, that his grasp of- the family idea intensifies his vision, of the Fatherland and that sense of brotherhood which cements the bond of sympathy between him and those who are fighting for the same cause.

I was with the Italian soldiers during those days when the fate of Verdun hung in the balance. Peasants from the Abruzzi and Piedmont and Tuscany, men who never before had had experience of the world beyond their little farms and workshops, eagerly scanned the morning papers for news of their French comrades. Groups of soldiers gathered round the lucky individual who had received a copy of the "Corriere" or "Tribuna" in his morning's post. The news was constantly received with exclamations of pride, and one often heard expressions of sorrow because the weather conditions prevented Italy from lending a helping hand by striking vigorously on her own front.

For the Italian soldier is always delighted to feel that he fights in concert with his Allies. Tell him that the Franco-British troops are striking on the Somme, the news will fire his spirit and lend new strength to his blow.

That capacity for grasping a world-wide situation seems to be due to something racial in the Italian character. I suppose it is a heritage from their Roman forbears. And I imagine it accounts for the fact that one hears more - of world politics than of war when mixing with the officers and men at the front.

When they discuss war it is generally on broad, strategic lines, and they constantly illustrate the argument by drawing diagrams on little slips of paper. But they are far more anxious to discuss politics with the stranger. They discover the main currents of British affairs far more readily than an ordinary Briton, and they unravel Balkan tangles as you will find them unravelled nowhere else. It is remarkable how many of the officers and men understand English. I should say that quite fifty per cent of the officers are conversant with the French tongue. In their dug-outs you will find copies of the "Times" and "Daily Mail," the "Journal" and "Temps," and "Echo de Paris."

When you are presented to the general who has command in the section wherein you are spending the day, he invites you to lunch, and you accept all the more readily because you imagine that you have struck a mine of military information. Do not think that it will be a ceremonial performance where strict military canons are enforced at table. I have dined at divisional headquarters where privates sat beside the commander and led the conversation, for this is a brotherhood of sacrifice where one man's blood is as precious as another's.

as seen by a French magazine - the new Italian brothers-in-arms

Desirous of Doing Things

If you think that the commander will confine himself to the discussion of military matters, you are mistaken. He will ask you about British workmen, the output of coal and munitions, the Irish question, and the attitude of the British Government towards different problems of world politics. Ask the ordinary officer what he thinks of the British Army. He will often begirt by telling you that he takes off his hat to the Navy. His mind being fixed on the whole European battle-line, he naturally considers the British Army in its relative importance. He admires its equipment and its solid staying power, and he fully realises that the British Empire is the main bulwark of the allied cause.

As to the bearing of the Italian in the actual fray, I doubt if our general idea of him is entirely correct. We are apt to consider him fiery and somewhat wanting in doggedness. Doggedness is so characteristic with ourselves that we are inclined to pin our faith to it and look for a corresponding share of it in other armies. It is true that the Italian is not dogged as is the British warrior, especially in passive trench warfare. He wants to do something.

Capacity for Team-Work

Ask him to build a bridge under fire, or to climb a mountain, and he will stick to his work as busily as an ant, even though his comrades fall and he is sorely wounded. He loves to conquer the "impossible" and achieve a sort of super-heroism. He will charge a battery with his bayonet. When he is brought in wounded, he is still in a sort of ecstasy ; his body is afire with a warlike incandescence, so much so that oftentimes he does not wince under the surgeon's knife. But if he be left too long inactive in front-line trenches his nerves are apt to suffer. This capacity for team-work is one of the most admirable of his qualities.

It is a mistake to compare one army with another, for each has its characteristic excellences. And this may be said of the Italians — that the manner in which they have grappled and overcome the difficulties of their particular front has compelled the enthusiastic admiration not only of their friends, but even of .their foes.

Italian uniforms from a German magazine