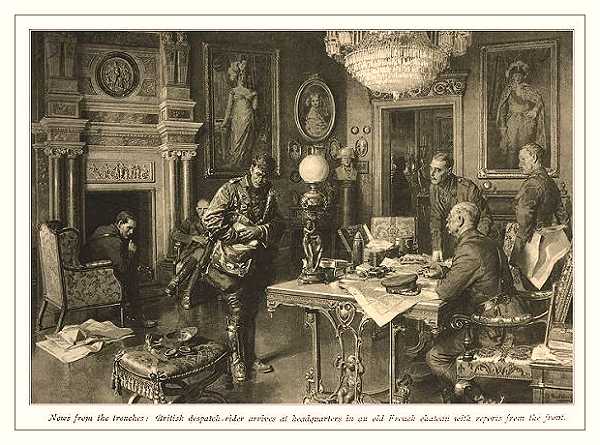

- from 'The War Illustrated', 9th March, 1918

- 'At Army Headquarters'

Contrasting Experiences from Various Fronts

delivering a dispatch at headquarters - illustration by Fortunino Matania

What a scene those words used to conjure up for me before I had ever seen the actuality for which they stood.

I used to imagine tall men with Wellingtonian noses or Napoleonic beetling eye- brows sitting at the receipt of despatches at least two a minute.

I could See them tearing open the envelopes brought in by panting despatch- riders, who had left their horses in a lather outside, flinging the reins to a sentry and rushing into the chateau or the cottage, as the case might be.

From time to time the tall men would spring from their chairs, cast a glance at one of the maps hanging on the walls, then jerk out some order, which a subordinate obediently hastened to write out and send off.

There was a bustle, a coming and going, an atmosphere of excitement, usually thrilling with good news, sometimes, perchance, with tragedy, much clattering of hoofs, much movement of marching men.

Army Headquarters may have been like that once. To-day they are seen under a much less dramatic aspect.

The sound I chiefly connect with them now is the click-clack, not of hoofs, but of typewriters. There is an air, not of romance, but rather of bureaucracy about them. They are extremely businesslike.

This is true, so far as my observation has gone, of Army Headquarters everywhere. Allowing for slight differences, due to national idiosyncrasies, such as the prevalence of pipes among British and of cigarettes among Russian Staff officers, they are all very much alike.

"G.H.Q." in Strange Places

Everywhere an atmosphere of studious calm, with hard work and long hours for the chiefs. Everywhere unutterable boredom for those who cannot find sufficient occupation, such as the members of foreign military missions. Everywhere that kind of suppressed mutual irritation, developing at times into hatred, which is found among schoolmasters and monks, and all who are obliged to live together in a circumscribed space.

The more remote the situation the more intolerable the boredom. The Grand Duke Nicholas had his Headquarters for a long time in a railway train on a siding in the Forest of Baranovitchi. No more devoted proof of brotherly affection has ever been given than was given by his brother Peter, who stayed there to keep him company. He saved himself from going mad by playing chess all day long with the chaplain.

No one but a Russian general would choose to live in a train, just as no one but a Russian admiral would have hoisted his flag as Commander-in-chief of the Baltic Fleet in a yacht moored alongside a quay at Helsingfors. That was where I found Naval Headquarters.

When the Tsar himself commanded the Russian Army the "Stayka," as G.H.Q. is called in Russian, was at a small town named Mogileff. Here the miscalled autocrat, who was rather an automaton in the hands of the Court camarilla, lived in a little house with his little son, and used to walk around unattended in the most unceremonious way.

Every morning he walked from his house to General Alexeieff's office, and had explained to him any change in the disposition of the troops, or any operations which might have been taking place. He had not much head for big subjects, but he was quick to grasp small points.

For example, a British general, who was very friendly with him, suggested one day that it might raise the spirit of the Russian people if their Emperor made speeches more often to encourage them. The Tsar said he did not like that kind of thing, it was too much like advertisement. The general persisted, and the Tsar said he would think it over.

Contrasting Commanders

A few evenings afterwards, as they sat down to dinner, the Tsar whispered to the general, "I've been doing some advertising to-day." He had been making a speech of the character suggested. Unfortunately, speeches were not enough. He should have added actions to his encouraging words, and disaster might have been avoided.

Alexcieff was as little like a soldier as it is possible to imagine a Chief of Staff, who is really Commander-in-Chief, to be. He is a small man with a large head, an unwholesome complexion, and an extreme shyness of manner. Far more of a professor than a fighting man, he was a marvellous campaign director. The final stages of the Russian retreat in the early autumn of 1915 were managed by him with consummate skill. "Anyone can conduct an advance," I remember a. famous strategist saying to me once ; "it is retreating which shows whether a commander has his wits about him." In this Vilna operation Aiexeieff was playing against the best German generalship and won the match.

To a quite different type belonged General Brussilolf. He was the dashing cavalryman, at home in any society, and master of several languages. The first time I saw him at his Headquarters he talked for an hour in the most frank and friendly tone. Yet he would have been, in some ways, a better commander than Alexeieff, for Alexeieff liked doing everything himself, whereas Brussilotf, good organiser that he was, understood that the chief ought to keep his hands free from detail.

Evicting an Intruder

When one went to see him his table was almost empty of papers. He .never seemed to be hurried, or even very busy. He kept his mind alert and ready for the big decisions. The smaller matters he left to his Staff, and, although they liked him, they all said that he was a chief who had to be exactly and instantly obeyed.

His Headquarters were at a town called Berdeecheff, where, out of a hundred thousand inhabitants, some eighty thousand are Jews, Jews in gaberdines, with ringlets on each side of the face, and little flat caps on their heads. Most of them spoke only Yiddish. It was an odd experience to hear what sounded like German talked openly in shops and streets when speaking German was forbidden all over Russia. Yiddish, a. dialect of German, cannot be forbidden, for a vast number of the Russian Jews have no other language.

In Berdeecheff I saw one day, in a small restaurant, an episode which remains my funniest recollection of the war. There rambled about the town a half-witted creature who begged cigarettes of strangers. While Arthur Ransome and I were having lunch the little restaurant was all of a sudden filled with a tremendous scuffling and fighting. The idiot. had seen us through the window and had slipped in. The waiter who was handing us potatoes had gone for him at once.

They struggled about the room, or rather, the waiter pummelled the idiot about with incredible rapidity. It was like two cocks fighting. The combatants seemed to be all over the place at once. Now on this side, now on that ; raising the dust, knocking knives and forks off the tables, filling the room with uproar.

At last the waiter got the intruder to the door, and with a neatly-planted kick, sent him into the middle of the road. Then he returned to us, and. without a word, as if such incidents were of the commonest occurrence, resumed handing us the potatoes. We had looked on speechless and spellbound, but now we broke into roars of laughter. We could not stop laughing. The waiter only shrugged his shoulders, and went away to fetch the next course.

A Close Shave

Rumanian Headquarters was for some months in a village school, where the pictures and diagrams, by which the children were taught natural history and arithmetic, still hung on the walls. After that they moved about very rapidly. We used to get to a town, organise a headquarters' mess, and start work. Suddenly news would come of another German advance. Off we went again.

The movement was almost as rapid as that of British Headquarters in the first weeks of the war. A distinguished officer, who then held a very high position in the "contemptible little Army," tells with sardonic humour the story of his being nearly cut off arid taken prisoner.

The Staff had arrived in. a village and taken possession of various building. The general was hard at work towards evening with his chief assistant. Suddenly his assistant remarked :

"Very quiet this village, sir."

"Good thing, too," said. his superior.

Pause.

"Seems to me unusually quiet, sir."

"Don't you make a mistake."

Another pause.

"I don't like this quiet at alt, sir."

"Then, for goodness' sake, get out and leave me in peace ! "

The assistant got out, and soon discovered that they were the only members of the G.H.Q. 'Staff left. They stood not upon the order of their going, but went. When they caught up they were greeted with, "Why, we thought you'd been captured by the Boche !"

"And I think," adds the story-teller, "they were rather sorry I hadn't been."