CHAPTER X

'the Agony of Antwerp'

In this drama of a gallant nation's sorrows, a spectacle which, the world over, must endear the name of freedom afresh to every heroic heart, no act has appealed more strongly than the gallant defence of Antwerp and its lurid close.

Once the commercial capital of the world, adorned, to quote the words of Motley, "with some of the most splendid edifices in Christendom," Antwerp has the honour which no vicissitudes can dim of being one of the earliest seats in Europe of public spirit and liberty. Nor is it easy to accept the belief that such a city is destined to become merely the gateway of an ignoble Prussia.

As affairs stood at the beginning of October, the Germans were anxious to gain some decisive success. So far, the war had failed to yield any. They had met with heavy reverses. They were feeling sharply already the economic effects of the virtual closing of the Rhine. In the belief that, Belgium subjugated, no combination of Powers would be able to tear it from their grasp, and urgent to complete that subjugation while time yet offered, they pushed the siege with all the energy they could command.

This hurry, as at Liege, proved prodigal. An attempt to storm fort Waelhem alone cost nearly 8,000 men killed and wounded. As the reduction of the outer fortifications threatened to be slow, the 11- and 12-inch mortars at first employed were reinforced by the new 16-inch mortars throwing shells more than 800 lb. in weight. These ponderous engines, transported with immense labour into France, were, with equal labour, hauled back across Belgium, and on the foundations of demolished buildings, placed into position against the forts situated to the south of the Nethe. At the same time, in order to explode magazines and to fire buildings, shells were used filled with naphtha, designed to scatter a rain of blazing oil. The besiegers' loss of life in the attempt to storm Waelhem was avenged by destroying the city waterworks, situated close to that fort. This reduced the population of Antwerp to the supply afforded by such wells as were within the city limits and made it impossible to put out fires should they occur.

By October 5, forts Waelhem, Wavre, Ste. Catherine, and Konighoyck had been overpowered, and the fort of Lierre silenced. All these forts lie south of the Nethe. The villages adjacent were burned to the ground. At Lierre, a mile to the rear of fort Lierre, a German shell crashed through the roof of the Belgian military hospital. Some of the wounded men lost their lives. On October 7, after a furious concentrated bombardment, fort Br6echem was a heap of ruins.

The way was thus open for a final attempt, under the weight of the German guns, to win the passage of the Nethe. Against great odds the Belgians offered a stubborn resistance. The action was one of the most bloody in the Belgian campaign. In it King Albert was wounded, though happily not seriously. This was the second injury he had met with. All through the war he had taken an active part with his troops, encouraging them in the trenches, braving every risk.

At the instance of the Belgian Government, the British sent to Antwerp on October 3, under the command of General Paris, of the Royal Marine Artillery, two naval brigades and one brigade of marines, a total of 8,000 men, with heavy naval guns and quick-firing naval ordnance mounted on armoured trains.

The Belgian command devolved upon General de Guise, military governor of Antwerp, one of the youngest, but also one of the ablest of the generals of the Belgian army. On both sides, the passage of the Nethe was disputed with desperate determination. The German attack at this time was directed, not only against the Belgian position north of the Nethe, through Linth and Waerloos, but with particular energy against forts Lierre, Kessel, and Broechen. These forts still held out. They covered the left flank of the defence. The right flank, protected by the flooded area along the Rupel, was unassailable.

Regardless of losses, the Germans worked day and night to float into position and complete the parts of seven pontoon bridges they had put together on the reaches of the river beyond the range of the forts. It was evident that if they could turn the left of the Belgian defence by destroying fort Broechen, and so breaching the outer defences at that point, just to the north of the Nethe, they could, having crossed in force farther up the stream, launch a formidable flank attack, which must compel the whole Belgian and British force to withdraw.

It was on the Belgian left, however, that the British naval brigades and marines had been posted. With the support of the naval guns, forts Lierre, Kessel, and Broechen defied all the efforts to reduce them. Very soon the fact became evident that this plan of turning the defence was impracticable. Hidden in bomb-proof entrenchments, the British suffered comparatively few losses, despite what seemed an appalling rain of shells. On the other hand, the naval guns, commanding the course of the river over a reach of ten miles, speedily made havoc of every attempt to cross.

In these circumstances, the Germans changed their tactics. They resolved upon a frontal attack through Duffel. Against the Belgian lines, a furious bombardment was concentrated. Under cover of this, and notwithstanding that, for a mile beyond the banks of the river, the country had been flooded, they advanced in masses to rush the passage. Simultaneously, and to prevent this attack being enfiladed by the naval guns, they made a feint of attempting to force their way over at Lierre.

Their losses were immense. Repeatedly their shattered columns were thrown back. For two days, at appalling sacrifice, they fought for the passage. On the British position the attack made no impression. But at daybreak on October 6, following an assault delivered in overwhelming force, the enemy succeeded at length in gaining a foothold on the north bank near Duffel, and in holding it despite all the efforts of the Belgians to dislodge them.

The Belgian army was obliged to fall back, and with them the British contingent, but it is evidence enough of the character and vigour of the resistance that, heavily outnumbered though they were, the Belgians, in retiring upon the inner defences of the fortress, left the Germans unable immediately to follow up their advantage. The British force withdrew without the loss of any of its guns. Indeed, the naval guns and the armoured trains covered the retirement so effectually that it was impossible for the Germans, until they had transferred their heavy artillery to the north of the Nethe, to press the retreating forces.

Beyond the boom of the hostile guns away to the south, and the nearer crash of the fortress artillery in reply, those within the city had, during these days of stress, little idea of how affairs were really going. A picture of the scene on the night of Tuesday, October 6, is given by the special correspondent of the Daily Telegraph :

“The night was so impelling in its exquisite beauty that I found it impossible to sleep, or even to stay indoors.

“On the other side of the river the trees were silhouetted in the water, the slight haze giving a delicious mezzotint effect to a scene worthy of Venice. As I walked along the stone-paved landing piers the contrast between the beauty of the picture and the grim prospect of what the death-dealing machinery all along my path might make it at any moment was appealingly vivid.”

Within a few hours, however, the scene changed with what to most in the city seemed almost startling suddenness. Following a proclamation by the authorities warning all who could to leave Antwerp as soon as possible, began an exodus the like of which has not been witnessed since the days of "the Spanish Fury." The same eye-witness proceeds :

“All day the streets have been clogged and jammed with panicky fugitives fleeing from a city which, in their terrified imagination, is foredoomed. Every avenue of approach to the pontoon bridge across the Scheldt leading to St. Nicolaes has been rendered impassable by a heterogeneous mass of vehicles of every size and kind, from the millionaire’s motor-car to ramshackle gigs loaded up with the Lares and Penates of the unfortunate fugitives.”

“Half a mile or so further on moored alongside each other were two of the Great Eastern Railway steamboats, which ply between Antwerp and Harwich, or, as at present, Tilbury. In view of the very great pressure of passengers, both were to be despatched. I walked through them. Each was filled to its utmost capacity with refugees who might have been sardines, so closely were they packed. In every chair round the saloon tables was a man or a woman asleep. Others were lying on the floors, on the deck, in chairs, or as they best could to seek a respite from their fatigues, a few, realising that theirs would be but a very short night-the boats were to sail at dawn so as to have as much daylight as possible with which to navigate safely the dangers of the mine-fields preferred to walk about on the jetty discussing the while their hard fate.”

The St. Antoine, the leading hotel of Antwerp, has for some weeks past been the temporary home of the various Foreign Ministers, but with their departure to-day has closed its doors. Last night it was the scene of an affecting leave-taking by the Queen of the personnel of the British and Russian Legations, her Majesty being visibly moved. I am informed that the King sent to the German commander yesterday by the hands of a neutral attaché a plan of Antwerp with the sites of the Cathedral and other ancient monuments marked upon it, which he begged might be spared destruction. “

In the meantime, the besiegers had made an attempt to carry the inner defences by storm. It was disastrous. Describing it, Mr. Granville Fortescue says :

“In their advance to the inner line of forts the Germans literally filled the dykes with their own dead. Coming on in close formation, they were cut down by the machine guns as wheat before the scythe.

Realising that it was, to all intents, impossible to carry the inner defences by storm, and that the garrison must be forced to surrender by the destruction of the place, the Germans, who had by this brought their great guns within range of the city, opened from their new positions along the north side of the Nethe a bombardment which, for sustained fury, has rarely been equalled.”

The bombardment began at midnight on October 7. From that time shells rained upon the place. The havoc, heightened by bombs thrown down from Zeppelins, speedily, and especially in the southern quarter, caused destructive fires. Viewed from afar - the fire was seen from the frontier of Holland - this great and beautiful seat of commerce, industry, and art, one of the glories of Europe, looked during those terrible hours like the crater of a volcano in eruption, with a shower of shooting stars falling into it. Silhouetted against the glare, its towers stood luminous amid the fiery light. Highest of all the incomparable spire of its cathedral pointed, as though a warning finger, into the dark sky.

For some time before midnight, the roar of the cannonade had ceased. The enemy's guns had for a spell become silent. To the deep hay of the cannon on the defences there came no answering defiance. At last even the guns on the defences had suspended speech. Mr. B. J. Hudson, of the Central News, one of the last English correspondents to leave, says :

“There was, uncannily enough, a grim calm before the midnight hour and the darkened city was like a town of the dead. The footsteps of a belated wayfarer echoed loudly.

Then suddenly came the first shell, which brought numbers of women into the streets, their anxious object being to discover whether the bombardment had really begun. Very closely did the roar of the guns and the explosion and crash of the striking shells follow each other. All over the southern section of the city shells struck mansion, villa, and cottage indiscriminately. Then the fortress guns, the field batteries, and the armoured trains opened out in one loud chorus, and the din became terrific, while the reflection in the heavens was seemingly one huge, tossing flame.

From the roof of my hotel the spectacle was an amazing one. The nerve-racking screech of the shells- the roof-tops of the city alternately dimmed, then illuminated by some sudden red light which left the darkness blacker than before -and then the tearing out of roof or wall by the explosion, made a picture which fell in no way short of Inferno. The assurance thus given to the population that the Germans were fulfilling their threat to bombard a helpless people, sent the citizens to their cellars, as they had been advised to go by the local papers of the day before.

About nine o'clock in the morning the German fire once more became heavier, but the screaming of the projectiles and the thunder of falling masonry left the fugitive population quite unmoved.

I noticed in one case a family of father, mother, and three small children who absolutely ignored the explosion of a shell some sixty yards in their rear, moving stolidly on.

About ten o'clock one of the petrol storage tanks in the city was hit and fired, and one by one the others shared its fate.

All along the River Scheldt quay barges and small steamers were taking on human freight as rapidly as they could, charging the wretched people 20 francs a head for the brief trip into Dutch territory.

As soon as the flowing spirit from the petrol tanks began to come down the stream something like a panic at last broke out. Those on board the steamers yelled to the officers, pointing to the danger and crying, "Enough! Enough!" Those on the quay, unwilling to be left behind, made wild rushes to obtain a place on the boats.

I saw one woman drowned in one of these rushes, while her husband - rather more lucky - fell on the deck of a boat and escaped with an injured skull. Women handed down babies, young children, perambulators, and all manner of packages, and then themselves scrambled on to the decks, using any precarious foothold available. It was a wonder that many were not drowned or otherwise killed.

Eventually the captains of the river craft, having gained as many fares as could safely be taken, sheered off, leaving many thousands still on the quay-side.

Still the shells were falling all over the town. The smoke from the blazing petroleum and the burning houses rose in great columns and must have formed an appalling sight for the people as far north as the Dutch town of Roosendaal.

What the position is outside the city walls we do not know. We hear our guns crashing out loud defiance to the enemy in a persistent roar; we hear the enemy's reply almost as distinctly. . . "

All that night and next day the stream of fugitives poured out-westward towards Ostend, northward towards Holland. Of the scene at Flushing, Mr. Fortescue wrote :

“Hordes of refugees fill this town. Some come by train from Roosendaal, others have escaped from the city by boat. All sorts of river craft come ploughing through the muddy waters of the Scheldt, crowded to the gunwales with their human freight. Tugs tow long lines of grain-lighters filled with women, children, and old men.

Their panic is pitiful. Since the first shell shrieked over the city a frightened, struggling mob has been pressing onward to escape the hail of fire and iron. Imagine the queue that shuffles forward at a championship football game increased a hundred-fold in length and breadth, and you will see the crowd moving to the railway station. Another throng fought their way to the quays. All the time German shells sang dismally overhead; for the most part they fell into the southern section of the city.

From the refugees I hear the same pitiful tales I have heard so often. A mother with two girls, one four and the other three, was torn from the arm of her husband and pushed on a departing boat. All through the panic of flight it has been "women and children first." Those who are here bear witness to the bravery of those who defend the city.

But if the besiegers had imagined that they were about to reap any solid military advantage, a disappointment was being prepared for them. For six days they had striven to cross the Scheldt at Termonde, and striven without success. The objective was to invest Antwerp from both sides of the Scheldt, and thus either for the remainder of the campaign to imprison the Belgian army, or to destroy it, amid the ruins of Antwerp, by their shell fire. That would have been a military success of an important character. Not only would it have left Belgium for the time being at their mercy, but it must undoubtedly have a moral effect not to be ignored.”

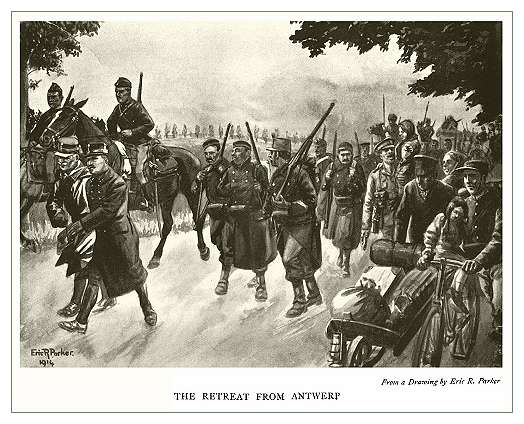

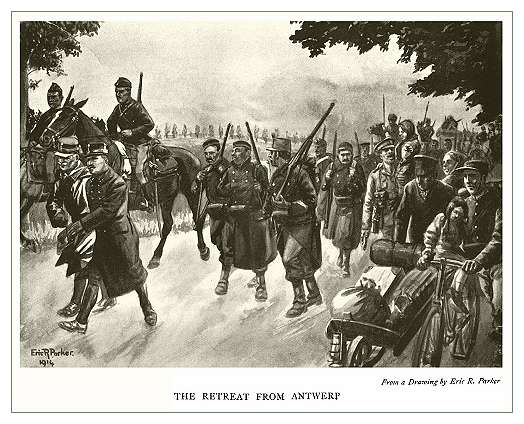

On October 8, however, the invaders had gained a passage over the Scheldt at Termonde, and had compelled the Belgian force Opposing them, much inferior in point of numbers, to fall back upon Lokeren. That place is on the line of communication between Antwerp and Ostend. In view of this danger, the evacuation of Antwerp became a necessity. The danger had been foreseen. The Belgian authorities indeed had already arrived at their decision. It is now known that this had been reached on October 3, and that the object of the small British reinforcement was to enable the evacuation to be accomplished. That object they fulfilled. By the timely warning given to the population nearly 150,000 had already been enabled to escape. All the available shipping in the port was used for transport purposes. The rest, including some 36 captured German merchant steamers, which could not be removed owing to the neutrality of Holland, was blown up and sunk in the docks. Objects of value were removed, and such stores as could not, and were likely to be of value to the enemy, were destroyed. The Belgian Government, on October 7, transferred itself to Ostend.

The Belgian army followed. By the morning of Friday, October 9, the evacuation had been completed. All the guns on the abandoned defences were spiked. Under the command of General de Guise, however, the forts controlling the approaches on the Scheldt continued to hold out.

In the meantime, the Germans had been pressing their attack upon Lokeren. The main portion of the Belgian army and 2nd British Naval Brigade, as well as the Marines, retired upon Ostend while the communications remained open. The first division of the Belgian army, which had been the last to leave Antwerp, and had been engaged in rendering the place useless to the besiegers, retreated fighting with the Germans north of the Scheldt a succession of rear-guard actions.

In the face of impossible odds, the 1st British Naval Brigade, now without the support of their heavy guns, were forced, fighting tenaciously, across the Dutch frontier at Hulst. A division of the Belgian army were also compelled to cross the boundary into Holland.

Just after noon on October 9, the besiegers entered Antwerp by a breach they had made near fort No.3 on the south-east side of the inner line of works. By then, the burning and ruined city presented the appearance of a tomb. What remnant of the population remained were in hiding in their cellars. Every person of authority had fled. Amid this scene of wreck and desolation, the Germans made their entry and installed their government. But the Belgian army had once more eluded their grasp, and with the navigation of the Scheldt closed, the possession of Antwerp, gained at the sacrifice of so much blood had become a possession presenting no compensating military advantages.

At the time these lines were written, the record, as already said, remains incomplete Enough, however, has been outlined in this brief sketch to prove that the struggle and the sufferings of Belgium form one of the bravest efforts ever made for a people's freedom, and a protest against the policy of rapine that can never fade from the memory of civilised nations, nor fail to command their admiration and their respect.

1914