from :

The Great World War

vol 1 The Gresham Publishing Company Ltd. (January 1915)

from 'The War Illustrated', a British newsmagazine

THE FALL OF ANTWERP

(September-October, 1914)

Antwerp's Value to Germany - Entry of Belgian Army - Antwerp's Defences - German Plan of Operations - The First Forts to fall - Belgian Appeal for British Help - Mr. Churchill's Visit - The British Expedition Justified - Evacuation of the City - Disasters to Naval Division - A Costly "Mistake" - Fate of the "Missing" - The Larger Scheme of Operations Involved - Sir Henry Rawlinson's Army - The Final Flight from Antwerp.

The fall of Antwerp demands a chapter to itself. Other incidents in the agony of Belgium filled the world with greater horror, but no previous event in the whole of that theatre of war was fraught with such deep dramatic interest for Britain, or caused so much exultation in Germany. Antwerp, the Liverpool of the Continent as it has been called, with its four hundred thousand inhabitants, its vast potentialities in the shape of a war indemnity, and its miles of docks, was a prize rich enough in itself, but above all else its capture was regarded as a vital blow at the enemy of enemies, a preliminary to The Day when the might of Germany would strike at the heart of Britain itself. That, at least, was the triumphant point of view of Pan-Germanism, which naturally made the most of it after the disastrous failure of the dash for Paris.

When King Albert and his heroic army - still, as we have already seen, defending their land step by step against overwhelming odds - retired to Antwerp, within what were regarded as its impregnable defences, the Germans made one last characteristic attempt to secure the Belgian king's neutrality. Belgium, it was pointed out, had already suffered more than enough; if King Albert would but accept the inevitable, and remain with his army inactive in Antwerp, that city would be spared. The answer of the King and his ministers was as honourable and determined as when the Kaiser sent his infamous ultimatum on the eve of his invasion. There was extraordinarily little excitement in the city itself when the investment began. Antwerp had known too many sieges in the past, and had too much faith in her defences, to realize the hopelessness of her position against guns of such overwhelming power as the enemy now had in the field. A glance at the accompanying map of Antwerp's serried rows of fortified positions suggests, on the face of it, that the faith of the citizens was justified. It was a faith shared by most military experts until the revelation of Germany's giant howitzers cast all such calculations to the winds. By their gallant sorties and counterattacks, in the course of which such neighbouring towns as Termonde, Malines, Alost, and Aerschot constantly changed hands - suffering irreparably in the process-the Belgians gave constant proof of their power to check and hamper the German advance; their ancient strategy of flooding portions of the surrounding land heavily handicapped some of the enemy's operations; mile upon mile of barbed and electrified wire threatened disaster to any infantry attack; beautiful suburbs were levelled to the ground-at a loss, it has been estimated, of no less than £ 16,000,000 - in order that no possibility of cover could be found there by the enemy. All, however, was in vain. As soon as the Germans began their bombardment, on September 28, .the critical nature of the situation was obvious. While the enemy could reach the outer line of forts at an effective range of nearly 8 miles, the Belgians had no gun which could fire at a greater distance than 6 miles.

In these circumstances there were few German attempts to rush the trenches and barbed-wire entanglements. The Germans had lost heavily enough in the previous attempts to cross the Scheldt between Termonde and the outer ring of forts in order to attack Antwerp from the west as well as from the south, where the German guns were preparing their devastating bombardment of the Wavre St.- Catherine and Waelhem sector of the city's defences. It was now left to the guns alone to hack a way through the outer and newer ring of forts - the defence-works designed by Brialmont, and armed with the only Belgian guns at Antwerp capable of resisting the assault of ordinary modern armaments. The inner line of forts was more than forty years old, and armed with out-of-date guns. The Germans therefore concentrated on the Wavre St. Catherine and Waelhem sector, and the forts, entirely at their mercy, were soon reduced to a heap of ruins. According to Mr. E. Alexander Powell, the American correspondent, who went right through the bombardment and fall of Antwerp, the Belgian general staff thought at the time that the Germans were using the same giant howitzers which demolished the forts at Liege, "but in this they were mistaken, for, as it transpired later, the Antwerp fortifications owed their destruction to Austrian guns served by Austrian artillerymen." The impotence of the Belgians, thus outdistanced, can be better imagined than described.

“Add to this", writes Mr. Powell, "the fact that the German fire was remarkably accurate, being controlled and constantly corrected by observers stationed in balloons, and that the German shells were loaded with an explosive having greater destructive properties than either cordite or shimose powder, and it will be seen how hopeless was the Belgian position. When one of these big shells - the soldiers dubbed them 'Antwerp expresses' - struck in a field it sent up a geyser of earth 200 feet in height. When they dropped in a river or canal, as sometimes happened, there was a waterspout. And when they dropped in a village, that village disappeared from the map."

Wavre St. Catherine, pounded to a shapeless mass of steel and concrete, was the first fort to fall. That was on September 29. On the following day Waelhem was silenced equally effectually, the Antwerp waterworks, lying at the back of Waelhem, being destroyed at the same time. Through the breach thus made the Germans poured their masses of infantry, but, thanks to the desperate resistance of the Belgians, failed for the time being to cross the River Nethe towards the inner line of forts. Then apparently it was that the Belgian Government turned to Great Britain for help.

“In response to an appeal by the Belgian Government," to quote from Mr. Churchill's official announcement, "a Marine Brigade and two Naval Brigades, together with some heavy naval guns, manned by a detachment of the Royal Navy, the whole under the command of General Paris, R.M.A., were sent by His Majesty's Government to participate in the defence of Antwerp during the last week of the attack."

It is now a matter of history that Mr. Churchill himself preceded the expedition and inspected the Belgian position at Antwerp for himself, remaining on the spot almost to the last. "He repeatedly exposed himself upon the firing-line," writes Mr. Powell, "and on one occasion, near Waelhem, had a rather narrow escape from a burst of shrapnel."

Much more than the possible hope of saving Antwerp was at stake when this much- discussed British Expedition arrived at Antwerp. It was not possible to save the city, but every day that was gained in keeping a German army - probably numbering 150 000 men - too heavily engaged to assist in the desperate fight for the coast against the French and British was of vital consequence to the Allies' plan of campaign as a whole.

The marines from Ostend - some 2000 all told - were the first of the British reinforcements to arrive. They reached Antwerp on the evening of October 3, and at once restored confidence to the anxious populace as they marched through to the support of the exhausted Belgians facing the enemy on the banks of the Nethe. The remainder of the expedition - about 6000 officers and men of the Volunteer Naval Reserve - arrived on the 5th and 6th, and was at once rushed to the front. Mr. Powell, the American correspondent, bears testimony that, "they were as clean-limbed, pleasant-faced, wholesome-looking a lot of young Englishmen as you would find anywhere"; but no one pretended that they were fully trained and thoroughly seasoned troops.

In the nature of the circumstances this had been impossible. The men were chosen, as Mr. Churchill afterwards explained in reply to criticism in the House of Commons- "Because the need for them was urgent and bitter; because mobile troops could not be spared for fortress duty; because they were nearest and could be embarked the quickest, and because their training, although incomplete, was as far advanced as that of a large portion not only of the force defending Antwerp, but of the enemy forces attacking".

Their courage under fire has not been disputed, and to the best of their ability they fulfilled the dangerous duty assigned to them. That duty formed at the time part of a large operation for the relief of the city planned by the Franco-British armies on the Belgian frontier, but "other and more powerful considerations", as it was officially explained, prevented this from being carried through.

Meantime the Belgian army and the British Marines had successfully defended the line of the Nethe River up to the critical night of October 5. Early on the following morning, however, a furious German attack, supported by powerful artillery, forced the Belgians on the right of the Marines to retire, with the result that the whole of the defence was withdrawn within the line of the inner and weaker chain of forts. Thence-forward it was merely a question of time for the Germans to bring up their guns and hold the city itself at their mercy. It was not even necessary to employ their heavy howitzers for that purpose. All through October 7 and 8, however, the inner line of defences was maintained while the bombardment of the city began. Our Royal Marines and Naval Brigades distinguished themselves both in the trenches and the field, and, with their gallant comrades, the Belgians, could have held out for a longer period, but not long enough - to quote from the official account - to allow of adequate forces being sent for their relief without prejudice to the main strategic situation.

On the 8th the enemy began to press strongly on the lines of communication near Lokeren, and though the Belgian forces defending this point fought, as elsewhere, with the greatest determination, they were gradually pressed back by the sheer weight of superior numbers. Thereupon the Belgian and British military authorities decided to evacuate the city, the British offering to cover the retreat. General De Guise, however, who was of course in supreme command, desired the British expedition to leave before the last division of the Belgian army.

How it was that the German Commander-in-Chief, General von Beseler, had not previously made desperate efforts to cut off all retreat westward is a mystery which remains unsolved. It is true that while the bombardment of the city was in progress the Germans had returned to the attack on the Scheldt with the obvious idea of threatening the retreat of the allied troops; but, though the passage of the river was at length effected at various points, the Belgian cavalry, armoured cars, and other mobile forces told off for the purpose, prevented the Germans from achieving their purpose in that direction. Had the initial successes been followed up with greater vigour by the Germans there is little doubt that the whole of the British and Belgian forces would either have fallen into the enemy's hands or been forced into internment in Dutch territory. As it was, the retreat was not effected without lamentable losses. According to the Admiralty statement, issued on October 16, the three Naval Brigades, after a long night march on October 8 to St. Gilles, entrained, and - "Two out of the three have arrived safely at Ostend, but owing to circumstances which are not yet fully known the greater part of the 1st Naval Brigade was cut off by the German attack north of Lokeren, and 2000 officers and men entered Dutch territory in the neighbourhood of Hulst and laid down their arms in accordance with the laws of neutrality".

Later official facts and figures reduced the number of British troops interned to 1560, and explained the losses thus incurred as having been due to ''a mistake''. Exactly what happened is not clear, but from all accounts spies were infesting the whole country, and a plausible suggestion was made that the 1st Naval Brigade had been wilfully led astray.

Possibly it was just, as the official statement says, "a mistake". Some 20,000 Belgians also crossed into Holland and shared the same fate as their British allies. One of the naval men who got through safely - though having acted as a rear-guard he could not tell what was happening in advance - explained that in the course of the retreat they came within a few hundred yards of the Dutch frontier; that the night was very thick and foggy; and that to cross the border was a mistake that might easily have been made, especially as the men were worn Out after a week in which they had crowded the experiences of a life-time, with scarcely twelve hours' sleep since they embarked at Dover.

The heavy loss by internment in Dutch territory, however, was not the only disaster that befell the Naval Brigades at Antwerp. The official casualty lists showed that in addition to these 1560 unfortunates, as well as 32 killed and 189 wounded, 967 officers and men of the Naval Division were " missing". Of these last, 200 were known to have been captured while endeavouring to escape with a trainload of fugitive civilians. The truth seems to be that instead of the three naval brigades retreating together and entraining at St. Gilles, as suggested in the Admiralty statement of October 11, 1914, several battalions never received the order to retire, and were left stranded. When these battalions realized their desperate plight they had little chance of making good their escape. By that time the pontoon bridge across the Scheldt had been blown up by the Belgians - the sole remaining avenue of retreat from the city - while the Germans had seized the railway at Lokeren. Some of the missing naval men may have succeeded in slipping through to Holland, but the majority were captured, some 900 being officially notified on December 21 as prisoners of war at the Gefangenen-lager (prisoners' camp), Doeberitz, Germany. The 200 who were in the train already referred to, surrendered in order to save the civilian refugee passengers from the fire from the enemy's guns

In spite of these losses the great adventure, if it had failed to save the city, had proved of inestimable service to the Allies. As Lord Kitchener afterwards declared in the House of Lords, not only was the gallant Belgian garrison, with King Albert in its midst, safely removed by British efforts, but the delay which had been caused in the release of the besieging forces in front of Antwerp just gave time for Sir John French, by a bold forward movement, to meet the onrush of the Germans towards the northern coast of France, and prevent them from obtaining their objective.

Sir John French's own dispatch of November 20, 1914, served partly to pierce the mists which still obscured the nature of the larger scheme of operations, of which the naval expedition to Antwerp had formed part. In that memorable dispatch the Field-Marshal referred for the first time to the army, consisting of the 3rd Cavalry Division (Major- General the Hon. J. Byng) and the 7th Division (Major-General Capper), under Sir Henry Rawlinson, as placed under his orders by telegraphic instructions from Lord Kitchener. Although too late to effect its primary purpose of aiding the naval division to save Antwerp, the army under Sir Henry Rawlinson served after the fall of that city to cover and protect the withdrawal of the Belgian army, which reached the Ostend district on October 11, and joining forces with its allies, entrenched itself on the Ypres Canal and the Yser River. Here, as Sir John bore witness, the Belgian troops, "although in the last stages of exhaustion, gallantly maintained their positions, buoyed up with the hope of substantial British and French support". The revival of this indomitable army - reported by the Germans, in the first flush of victory at Antwerp, as virtually wiped out of existence - was a disillusionment which, with the empty husk of a deserted city, the blocked harbour and docks, and the wrecked lighting and other works, robbed the victors of much of their hoped-for reward.

The naval brigade also had succeeded in saving its armoured trains and heavy guns, which did not have time to play the decisive part expected of them in the last phase of the defence operations.

"The train", to quote from Mr. Powell's account, "consisted of four large coal-trucks, with sides of armour-plate sufficiently high to afford protection to the crews of the 4.7 naval guns-six of which were brought from England for the purpose, though there was only time to mount four of them - and between each gun-truck was a heavily armoured goods-van for ammunition, the whole being drawn by a small locomotive, also steel- protected."

More remarkable even than the retreat of the naval and military forces was the exodus of the people themselves in those last days of the defence. Though thousands of the population of Antwerp - especially the well-to-do - had already slipped away, it was not until the last moment that the bulk of the citizens would believe that their famous defences could be pierced before the Allies had time to come to their rescue. When they woke on the morning of October 7, to learn by proclamation that the bombardment of the city was imminent, and that everyone who could leave had better do so immediately, the effect beggars description. Not only were there some 400,000 of Antwerp's own population; at least another 100,000 had flocked into the city from the surrounding towns in their endeavour to escape from the invaders. It is estimated that in the appalling flight which followed, more lives were lost than in the casualties from German shot and shell.

"No one who witnessed the exodus from Antwerp", adds Mr. Powell, "will ever forget it. No words can adequately describe it. It was not a flight; it was a stampede. The sober, slow-moving, slow-thinking Flemish townspeople were suddenly transformed into a herd of terror-stricken cattle."

Was it to be wondered at after all the horrors of the German policy of "frightfulness " in other parts of stricken Belgium? Every road leading towards Ostend and the Dutch frontier became black with a hurrying crowd of fugitives carrying all that could be seized at a moment's notice; while every boat, from a merchant-steamer to a racing-skiff, was pressed into service for the escape by river - anywhere, anyhow, to escape beyond the reach of the ruthless invader. Hence, when the German hosts, after a bombardment in which comparatively little irreparable damage was done to the city itself, made their triumphal entry during the afternoon of October 10, passing in review before the newly appointed military governor, Admiral von Schroeder, and General von Beseler, it was more like a pageant in a city of the dead than in what but a short while previously had been one of the most thriving and hospitable towns in Europe.

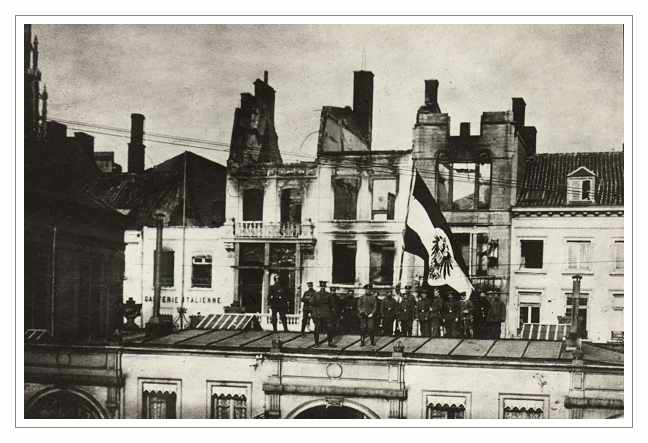

German soldiers raise their flag over former Belgian Military Headquarters

Here they pose in the courtyard of the same building