- The Fall of Antwerp

- from ‘The Great War in Europe’

- by Frank R. Cana F.R.G.S

THE TRAGEDY OF ANTWERP

CHAPTER VII

The Fate of Termonde and Malines - Antwerp a Thorn in the Side of the Germans - Germans Closing in on the City - The Forts Bombarded-British Reinforcements - The Forts Taken - Bombardment of the City - Scenes of Terror - Evacuation by Belgian and British Troops - One Hundred Thousand Fugitives - Importance of Antwerp - A Menace to Holland - King Albert and the Belgian Government -

During the "triumphal" advance of von Kluck on Paris, during his enforced retreat from the Marne, and while the battle of the Aisne dragged its slow length along, the Belgian army continued to harry the Germans in Belgium. Shortly after their state entry into Brussels the invaders had occupied both Ghent and Bruges. These were "open" cities, and no armed resistance was offered. Imitating M. Max, the burgomasters made the best terms they could with the enemy. The historic buildings suffered no damage either at Ghent or Bruges. To still the alarm of the coast dwellers, British marines were, landed at Ostend on 27th August, and despite raids by Uhlans, the Germans did not at this early period make any serious effort to reach the sea. The bulk of the Belgian army was kept behind the defences of Antwerp, but it held the country between Malines and Ghent, and by a thin strip of territory bordering the Dutch frontier was still in communication with Ostend. From Antwerp it made sorties which occasioned the Germans much loss and annoyance, as their line of communications was frequently threatened.

The conflicts between the Germans and the Belgians in the last days of August and the first half of September centered on Termonde, a town on the Dendre at its junction with the Scheldt, and roughly midway between Ghent and Antwerp, and on Malines (Mechin), an ancient picturesque city on the river Senne, midway between Brussels and Antwerp. Termonde and Malines thus covered the approach to Antwerp. Termonde, which had once been taken by the Duke of Marlborough - who destroyed nothing - was entered by the Germans on 4th September, and on the usual false pretence that the troops had been fired on by civilians the town was systematically destroyed. It was reduced to a ruin, more complete even than the ruin of Louvain. At first the Town Hall was left standing, but later in the month it also was deliberately burned down. Many of the citizens were deported to Germany. Malines fared somewhat better. The town itself, in consequence of the artillery fire directed on it, was not, for weeks, held either by the German or Belgian troops. The medieval Town Hall was destroyed, and the fine cathedral, with its famous chime of bells (rivalling those of Bruges), suffered much damage. Cardinal Mercier, Archbishop of Malines, who had gone to Rome to attend the conclave for the election of a new pope-returned to his see, the ecclesiastical metropolis of Belgium, to find it in a sad state. The art treasures of the city were removed at great peril, and under the fire of the German guns. Cardinal Mercier continued to live at Malines after its occupation by the Germans, and boldly exercised his ecclesiastical functions. In his New Year's Pastoral (1915) he gave great offence to the invaders by stating that 'Belgians owed no allegiance to Germany’.

For this outspoken declaration the Cardinal was placed under guard in his palace, and forbidden to leave Malines. We shall recur to this incident.

By the third week in September 1914 the movement initiated by General Joffre to outflank the German forces on the Aisne became known to the enemy, who immediately tried to counter it by extending their own forces on the right seawards. At the same time it was determined to make an end of Antwerp, and with it the Belgian army. By this time the German General Staff had realised the failure of their original plan. The advance on Paris had been foiled in very large measure by the resistance offered by Belgium and by the British Expeditionary Force. 'But for Britain," the Germans declared (and with a great measure of truth), "we should be now in Paris," and against Great Britain their next effort was directed. Zeebrugge, Ostend, Dunkirk, Calais, were to be seized, command obtained of the Straits of Dover, and the coasts of England threatened. First, however, Antwerp must be subdued. When this was accomplished the large force which was detained before that city would be free to operate in Flanders. And in itself Antwerp - one of the greatest ports of Europe - was greatly to be desired.

The new movement opened on 26th September with an advance on Malines, which was occupied on 27th September, and the next day the attack on Antwerp began. It must not be supposed, however, that it had been previously altogether immune. On the night of August 24-25 an airship dropped bombs on the city, which had thus the distinction of being the first city to suffer from aerial warfare. These bombs fell near the king's palace, the National Bank, a hospital, and other civic buildings. Five persons were killed and several injured, all civilians. From the first, therefore, the Germans directed their attacks from the air on non-combatants. The apparent object of the bomb-throwing was to kill the royal family of Belgium. Later, other airship attacks were made on Antwerp, but until the end of September the Germans had made no attempt to capture the city.

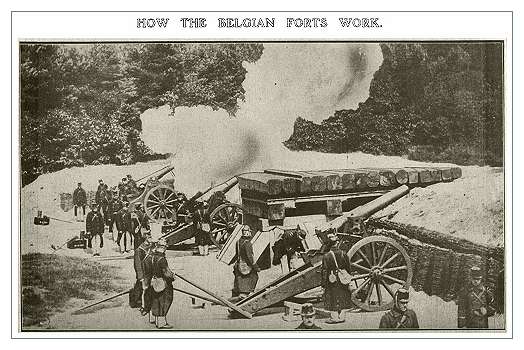

Antwerp was defended by a double line of forts, the outermost of which on the south, Wavre St Catherine and Waelhem, were close to Malines. On this side the Nethe and the Rupel rivers offered a further line of defence, and the country in this direction could be inundated. It was generally held that the Antwerp position was so strong that its investment would require an army of a million men, and that its capture must entail enormous losses on its captors. Unfortunately the defence of a place of so vast a perimeter demanded a larger garrison than was available; more-over, all the forts were not finished when the German attack developed, owing partly to the great expense of completing the fortifications, and partly, if rumour was correct, to the intentional delay of the firm of Krupp1 which had years previously contracted for the work, to deliver the big guns.

Events moved with amazing swiftness. On the 28th the heavy siege train brought up for the purpose attacked the Waelhem and Wavre St Catherine forts..

On the next day the magazine at Waelhem was blown up, and the Antwerp waterworks destroyed. The two south-eastern forts of Koningshoycht and Lierre were also temporarily silenced on the 28th, and a desperate attempt made to rush the Belgian trenches. Lierre, standing at the important strategic point of the junction of the Petit Nethe with the Nethe, was not destroyed by the first bombardment, but the resistance was seriously weakened, and on 4th October it was the object of a terrific cannonade. The enemy was determined to break through the ring of defence at all costs, and showed in the process an even greater disregard of human life than usual. The Belgian defenders, whose trenches were exposed to a terrific cannonade, had retired behind the Nethe on 2nd October Mowing up the Waelhem bridge behind them. The Lierre and Koningshoycht forts still offered resistance, but on the 3rd they were effectively silenced. On the 5th the enemy made repeated attempts to cross the river. During the day British marines and British naval armoured cars arrived to assist in the defence of the Nethe, and for that day the German attempt to force the river failed. The detachments attempting the passage were annihilated at each fresh attempt to throw a bridge across. They did cross on the early morning of the next day, by sheer weight of numbers, but they lost 20 000 men in the operation. On that same day Lierre was captured. On 7th October the enemy began to pour across the Scheldt at Termonde, and at two crossing places between that unhappy town and Ghent, and guns were placed in position to open on the inner line of forts.

Thus within ten days of the opening of the attack a place regarded as almost impregnable was on the verge of falling. As we have just seen, a British force arrived on 5th October to help in the defence. This force, 8,000 strong, was commanded by General Paris, and it had been landed at Ostend. Immediately afterwards (though nothing was publicly known in England about this movement for weeks afterwards) another British force, the 7th Infantry Division tinder Lieutenant-General Sir H. S. Rawlinson, and the 3rd Cavalry Division under Major-General J. H. Byng, was dispatched from England, and had completed its disembarkation at Ostend and Zeebrugge by 9th October It immediately seized Bruges and Ghent, from which towns the Germans withdrew, but it came too late to help Antwerp, for on the 9th of October the Germans had entered that city. The importance of holding Antwerp had been fully recognised by the British Government, and on 3rd October Mr. Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty, had paid a special visit to the city to confer with the Belgian Government and the military authorities. The plans of the British were laid on the assumption that Antwerp would be able to hold out at least a week or ten days longer than it proved able to do. By 5th October it was patent that the end was near.

The Queen of the Belgians, herself a Bavarian, left the doomed city, taking with her to England her three young children. The children found a hospitable home with Lord Curzon at his country house, while the noble-hearted and devoted Queen returned to Belgium to resume her place by the side of her heroic husband and King.

On the 6th of October the Belgian Government, the diplomatic corps, and the representatives of the Allies left Antwerp, the Government finding temporary headquarters at Ostend, and on the next day it was decided that the Belgian army should evacuate the city. "We were there in a hell," said one of the British marines. "No courage, bravery, or self-sacrifice could withstand the German heavy artillery." The roads to Ostend, to the frontier of Dutch Flanders, and to Roosendal, the frontier town of Brabant, were already thronged with crowds of terrified people escaping from the city, and every available craft at the quay side was laden with fugitives. There were no guns which could make effective reply to the 200 great siege guns of 11 in., 12 in., and possibly some of 16 in. calibre brought up by the Germans, and the British marines and Naval Reserve Men (many of the latter raw recruits), although they had the support of some naval guns, were as powerless as the Belgian defenders. Before the city was evacuated, however, pains were taken to diminish the value of the prize. The petrol tanks were emptied, much of the shipping in the harbour sunk, and the machinery of all the vessels destroyed, as were also large quantities of food and other supplies. Bridges were blown up, and the docks blocked by the sinking of lighters in the channel. A minor tragedy - but to the citizens of Antwerp a real tragedy - was the shooting of all the wild animals in the Zoo. One of the finest in Europe, the Zoological Gardens at Antwerp adjoin the central railway station, and are a fashionable resort. The danger of the lions, tigers, venomous snakes, and other deadly inmates of the cages breaking loose was, however, too great to be faced.

For two days before the bombardment of the city itself began there was a lull in the cannonade while the besiegers were moving in their guns to close range. At midnight on the 7th of October the bombardment of the city was opened. Incendiary shell rained down on the streets, and kindled many fires. The incessant am and the terror of the bombardment was made more horrible by the glare of the burning oil, which threw up black clouds of smoke, against which the lightning flashes of exploding shells showed with terrible brilliance.

Under the terrific bombardment the streets actually rocked, so that "to add to their troubles many of the fugitives suffered from sickness as in an earthquake. The fire appears to have been directed in a haphazard way on all parts of the city. Many houses were set alight, and shells hit the Palais de Justice and many other public buildings, and fell in the Place Verte close to the cathedral. Owing to the absence of water it was not possible to extinguish the fires, and great damage was done. But the city was not destroyed. Wholesale destruction was indeed no part of the plan of the invaders, since the "Queen of the Scheldt" was, they vainly hoped, to become a great German port.

Many of the inhabitants had already left; there was now an exodus of terror-stricken fugitives unmatched in our time, unmatched probably even in the brutal wars of antiquity. They were received at the Dutch frontier with human kindliness by the Dutch soldiers sent down, in keeping with the age-long tradition of Dutch hospitality, with food for the hungry, exhausted crowd, and as much as it was possible to do for the 100 000 who crossed the frontier was done, but their sufferings were still terrible.

Besides the fugitives, 2000 British marines and Naval Reserve men, and a large number of Belgian soldiers, were cut off by the Germans. They crossed the frontier, and were interned by the Dutch authorities. But the main Belgian army had safely eluded the Germans, was on its way to Ostend, and was still to deal many a serious blow at the enemy, and to aid effectively in blocking the march of the German troops southward. General Paris, of the Royal Marines, who commanded the British force sent to Antwerp, offered to cover the retreat, but the Belgian General de Guise desired that this post of danger should be held by the last divisions of the Belgian army. The naval armoured trains and heavy guns were brought away, and two of the three naval divisions reached Ostend in safety with the Belgian army, the retreat from Ghent onwards being covered by General Rawlinson's 7th Division. No opposition was made to the reoccupation of Ghent and Bruges by the Germans, who also, by taking Zeebrugge, obtained a seaport.

The sending of a small British force to Antwerp was bitterly criticised in the British Press. It was argued that a force should have been' dispatched sufficiently strong to continue the defence for some weeks, or that the Belgians should not have been buoyed up with false hopes. In so far as the force sent consisted of untrained men, the British Government cannot be freed from blame. The marines did not come under that category; there is no finer fighting force in the world than the British marine, and these were all seasoned men. But "'the Royal Naval Reserve men sent with the marines were mostly new recruits, very insufficiently trained, and there were among them, placed in the trenches to oppose the German advance, youths who needed elementary instruction as to how to fire their rifles. But the British intervention was justified, for it did cause a slight delay in the fall of Antwerp, and this delay, small as it was, did materially aid the strategy of the Allies. If, as it was hoped when the British reinforcements were sent, resistance could have been prolonged for another week, and the German guns and the German armies held up before Antwerp, the British army under Field-Marshal French would have completed its move to Flanders from the Aisne, and the plan with which that move was undertaken, the envelopment of the German right flank, might conceivably have succeeded. In addition to the military value of the brief delay in the fall of the city caused by the British intervention in Antwerp, the moral effect of an effort, however slight, directly to assist the Belgians in their dire need, was good. Sir John French, dealing with this point, declared

"The assistance which the Belgian army has rendered throughout the subsequent course of the operations on the canal and the Yser river has been a valuable asset to the allied cause, and such help must be regarded as an outcome of the intervention of General Paris's force. I am further of opinion that the moral effect produced on the minds of the Belgian army by this necessarily desperate attempt to bring them succour, before it was too late, has been of great value to their use and efficiency as a fighting force."

Naturally the jubilation throughout Germany over the fall of Antwerp was immense. General von Beseler, the commander of the besieging army, received the highest military distinction of the Prussian Order of Merit for his brilliant feat of arms. The failure of the great march on Paris and the growing difficulties of Germany on her eastern frontier made a "crowning mercy" of some kind absolutely essential to maintain the popular enthusiasm. Antwerp was a solid justification for national rejoicings.

Antwerp has been one of the great avenues of overseas trade into Central Europe ever since the Middle Ages, and none of the storms that have raged over her during the centuries, not even the "Spanish Fury" of the sixteenth century, destroyed the trade of this great North Sea emporium. Antwerp, Rotterdam, Amsterdam, Bremen, and Hamburg are old trade rivals, and since the dreams of Greater Germany took hold of German minds, Antwerp has been a coveted prize. Antwerp1 too, as Napoleon said, was a "pistol aimed at England's heart," or so it was hoped. To aim it at England's heart would, it was true, involve an attack on Holland, which commands both sides of the Scheldt estuary, but this inconvenient fact was not obtruded on the German public. The capture of Antwerp was a very serious menace to the Netherlands. The Dutch realised how dangerous a neighbour they had at the head of the Scheldt estuary. They knew that if the Allies were not able to drive the Germans out of Antwerp, the fate of Zeeland was eventually to be that of Belgium. Even if they had not been previously aware of this, the moral would have been made clear enough to them by the seemingly endless procession of men, women, and children. fleeing from the scream of shrapnel, and the blazing fires kindled by the German incendiary shells.

The German army made a triumphal entry into Antwerp with all the pomp of war, with many bands, and with colours flying. All arms were represented, and contingents from all the national armies - Prussian,. Bavarian, Saxon, and Austrian (from the outset Austrian artillery batteries were sent to the western theatre of war, the Austrian gunners giving valuable help to their German allies) - though few civilians waited in the deserted city to watch the ceremony. Yet particular care had been taken that the entry should, if possible, produce a favourable impression not only on the citizens, but on neutral Powers. The Emperor William had confided to the President of the United States that "his heart bled" for Louvain; there was to be no occasion for it to bleed again for Antwerp. During the bombardment there had been no purposeful firing on public buildings, and the entry was excellently stage managed. No one was molested, and the ranks of the incoming troops were only broken when a stalwart soldier stepped aside to play with and lift on to his shoulder a small child who stood agape on the roadside. How punctilious the conquerors were in their occupation of Antwerp is shown also in the following quaint story told by Mr. Alexander Powell, who witnessed the incident : *(see also Fighting in Flanders part 5)

Before the actual occupation half a dozen motor cars, filled with soldiers, drew up before the Hotel de Ville, and their spokesman, a young officer, stated to the doorkeeper, "I have a message to deliver to the Communal Council."

"The Communal Council," was the reply, "are at dinner, and cannot be disturbed. If monsieur will have the kindness to take a seat until they finish."

The young officer and his escort of spiked helmets waited for a quarter of an hour, at the end of which a councillor arrived to receive the message. "The message I am instructed to give you, sir, is that Antwerp is now a German city, and you are requested by the general commanding his Imperial Majesty's forces so to inform your townspeople, and to assure them they will not be molested so long as they display no hostility to our troops."

The reason why the Germans acted with such moderation - apart from the fact that many Americans and Dutch remained in the city, people whose tongues could not be tied - is obvious. An Antwerp destroyed would be of no value to them; nor could they obtain the result they desired unless the commercial activity of the city went on. Most of the citizens had fled, and unless they could be induced to return, the value of the rich prize would rapidly deteriorate. Proclamations from the German governor were posted in Holland, assuring the citizens of good treatment, and asking urgently for bakers and railwaymen, merchants and tradesmen to return.

Gradually, out of sheer necessity, and in the hope of saving the remnant of their homes, a considerable number of the people did return. Trade on a large scale remained, however, at a standstill. No merchant ship could enter or leave the city-none would take the risk of practically inevitable capture by the British. General von Schutz, German governor of Antwerp, announced that the city would have to pay an indemnity of £20,000,000, but it proved more easy to demand such a sum than to collected the money.

King Albert had been one of the last to leave the line of defence in Antwerp, and when on the day before the city fell he was urged to seek safety, he answered: "It is better to die here than to seek safety in a foreign land." He continued to act on this principle, and his presence constantly encouraged the soldiers. He endured the hardships and the dangers of the life of an ordinary soldier, and was over and over again to be seen where the fire was hottest, always calm and modest, with none of the pomp of royalty or high command. He accompanied the Belgian army in its retreat to Flanders. Here in the extreme south-west corner of Belgium the King fixed his headquarters. There was still a portion of Belgian soil untrodden by the foot of the invaders. The Kaiser had planned to declare the annexation of Belgium to Germany on the capture of the last remaining town of importance in the country, namely, Ypres, an event expected to happen by the end of October. Ypres, however, obstinately refused to capitulate, and the Emperor's plan was spoiled. The Belgian Government, it is true, had after a brief sojourn at Ostend removed to Havre (13th October), but it was still in being, and, as will presently be told, the armies of Field-Marshal French, of the King of the Belgians, and of General Foch maintained their foothold in West Flanders in spite of the fifteen army corps sent against them.