from the book

Sexual History of the World War

by Magnus Hirschfeld 1930

Note : Posting this chapter from Hirschfeld's book does not imply that we are in accord with all of his statements and opinions. In fact, Hirschfeld's 'Sexual History of the World War', while extremely interesting from an illustrative point of view is as far as the text goes, a somewhat meanspirited and uncharitable work. The subject matter is original and has not been previously, nor since been written about in such an extensive manner, but Hirschfeld's world view is a gloomy one to say the least and the motives he attributes to nurses in specific and people in general are base and ridden with suspicion. He is not unlike a dirty minded teacher who sees naughty and nasty behavior in almost everything and who habitually attributes foul motives to otherwise innocent and normal behavior.

That said, his writing is interesting and original, especially since it is based on testimony from German and Austrian sources. Perhaps he is typical of the pessimistic minded thinker of the 1920s and 30s, disillusioned and fearful for the future.

Chapter 3

EROTICISM OF NURSES

Sexual Curiosity of Nurses - Nursing as Sex Outlet - Erotic Nature of Occupation- Coprolagnic Pleasure - Their Demoralizing Influence - Chronique Scandaleuse of Amatory Relations - Parisian Prostitutes Disguised as Nurse - Nurses' Garb Used in Shady Dealing - Erotic Determinants of Nursing - Curious Pathologic Cases - The "Love Expender" - The Evil Reputation of Nurses - Strange Visits of Women to the Trenches - Nurses in Khaki - Sadistic Aspects of War Nursing - Erotic Stimulation of Bloody Deed - Abuse of Enemy by Women - Reaction of Soldiers to Lusts of Nurses

__________________

In two ways did woman come into direct contact with the actual conduct of war: first as nurse, and, secondly and less commonly, as active warrior. In this chapter we wish to consider the erotic motives which play a greater or lesser role in nursing.

That the care of the sick is an essentially female occupation which is based on the natural characteristics and disposition of woman has long been known, nor was the knowledge of this fact impaired during the war. First, because all the unfavorable experiences of the war in this respect to the contrary notwithstanding, the old point of view was retained anyhow; and secondly, because the warring states were too busy replacing male workers by females in order to release as much human material as possible for direct participation in the waging of war.

In regard to our first point, the question of the natural disposition of women for the care of the sick, the connections with sexuality had long been apparent. Nevertheless in this respect too the war purveyed valuable contributions for the deeper understanding of the female psyche. In all too many cases one was compelled by the experiences of the war to drop the assumption of a casual relationship between female pity and an internal inclination to the care of the sick. On purely speculative grounds Weininger had come to this conclusion long before the war even though he still maintained a belief in the natural capacity of woman for the care of the sick:

"It is especially the generosity of the woman and her pity which has given rise to the pretty legend of the psyche of woman and the decisive argument of all belief in the higher ethical status of woman - as nurse, as merciful sister.... It is short-sighted to hold woman's nursing of the sick as a proof of her pity, for the opposite conclusion seems rather to follow from the fact. Man is so constituted that he could never be an onlooker of the pains of the sick; he would always suffer so much under these conditions that he would be completely undone. For that reason the care of the sick would be impossible for him. Anyone who has observed nurses closely has noted with astonishment that they remain unmoved and tender even under the most frightful agonies of a dying man and so it is obvious that a man who would be unable to go through such a spectacle would be a bad nurse. A man would wish to alleviate the pain, to stay death, in a word, to help; where he would be unable to help there would be no place for him. Then the female nurse would have to come in to do her share. However, it would be quite unjust to regard their value from any but a utilitarian standpoint."

It must be admitted that Weininger was right even in his last sentence. During the war the utilitarian standpoint was so dominant that all others receded before it. The female nurse was employed and the abuses which inevitably followed on the widespread usage of this institution were permitted to go unobserved. And it was quite clear that a considerable portion of the female nurses were impelled to nursing by quite other than patriotic and humanitarian motives.

It is a known fact that it was always women of the higher ranks who, especially in the first months of the war, crowded the steps of the train depots where the transports bearing wounded soldiers stopped, and called into being a cult of the wounded whose erotic background did not remain concealed, even to the public opinion that at the beginning was so enthused about the war and so inclined to overvalue all patriotic services. Whether the erotic or the play motif predominated in this depended on the situation in question. It must not be supposed, incidentally, that the play motif was a rare thing. In a brochure on the role of woman during the war which the French academician, Frederic Masson, issued in 1915 we find the statement that "certaines femmes serajent disposées a faire jou-jou avec les blessés." And the same author in speaking of the abundant proofs for the striking similarity of conditions in all the warring states speaks of the cult of the wounded among the French women as a temporary and effective substitute for the five o'clock tea and the most titillating sort of flirtation.

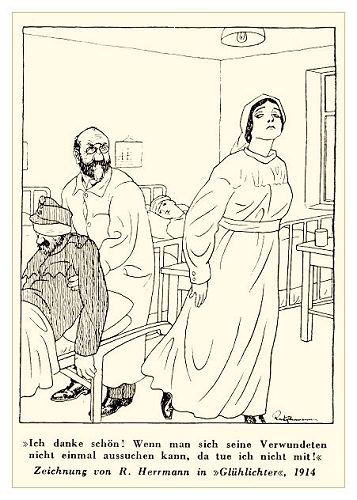

In other cases the care of the sick exercised by these well-situated dilettantes consisted of the most oppressive annoyances - concerning which many tales were current during the war. One of the many popular anecdotes which we now quote is characteristic of the opinion of soldiers about the cult of the wounded exercised and developed at their expense:

A wounded soldier lay still and stark in a hall in which the professional forces of the Red Cross were exercising their difficult duties quietly and satisfactorily. But apart from these professional forces a number of women came into the ward during the day- women of the highest rank, women who were ignorant of these methods, but women who possessed an unconquerable impulse to show their good will. They had done one little thing or another and so it had been difficult to prohibit them from entering the ward and trying to make themselves useful. One such lady came over to the wounded soldier who had to lie still.

"Can I do something for you perhaps?"

"No. I thank you."

"But perhaps I ought to wash your face a bit with vinegar water."

The answer was "Hm." The lady took the little sponge which was at hand, dipped it into the water which was prepared and then drew it over the face of the wounded man-a procedure which had been shown her.

"Do you perhaps want something else?"

But now the simple Bavarian could no longer contain himself. "Do you know, I did not want to disturb your pleasure, but you are without exaggeration the sixteenth one that has washed my face today."

In another connection we have already referred to the fact that serious scientists have regarded the nursing activities of the women as being one way of sublimating the libido and achieving sexual pleasure. This was especially the case among the volunteer nurses who were recruited from the best circles. At least a considerable proportion of these women had from the start no trace of any ethical motive; and the incapacity of the women recruited from the upper class to carry out the very heavy and unpleasant task of caring for the sick was there even when her activity was not merely a social sport with greater or less erotic coloration. For the patient always had the feeling of insulting the high-born condition of his nurse by requesting the lowly and rather nasty things that he needed. The Hungarian soldier who tortured himself for a half-day because he did not have the courage to demand of his fine and distinguished volunteer nurse the requisite vessel is one case among thousands. This reticence was also observed in the relations with the professional nurses but of course to a much lesser degree since, for the latter, it was a question of elementary professional duties.

Remarque has left us a contribution to this question. His hero and a comrade are riding homeward in the wounded car. During the night the hero wakes and turns to his comrade:

"Do you know where the latrine is?"

"I believe that to the right you have the door."

"I'll see." It is dark. I feel for the edge of the bed and want to slip off carefully but my foot finds no support. I begin to slip. My plaster cast leg is no help and with a crash I am lying on the floor. "Damn!" say I.

"Have you bumped up against something?" asks Kopp.

"You could jolly well have heard the noise," I growl back. The door opens behind us in the car, the sister comes in with a light and sees me. "He has fallen out of his bed."

She feels my pulse and my forehead. "You have no fever."

"No," I agree.

"Were you dreaming then?" she asks.

"I suppose."

And so I again avoid asking my question. She looks at me with her blue eyes. She is so clean and lovely that it is impossible for me to tell her what I want. I am again lifted up and when she goes out I try once more to slip off the bed. If she were an old woman it would be easy for me to tell her but she is very young-twenty-five at the most and I just can't bring myself to tell her what I want.

Now Albert comes to my help and he isn't quite so hesitant about the matter because, after all, it doesn't concern him. He calls the sister and she turns around.

"Sister," he says, "he wants - ." But Albert also is ignorant of the term to use, a term that will be decent and inoffensive. We have one word for it when we talk among ourselves but not here before such a lady. However, just then he remembers something from his school days and he finishes the sentence with "He would like to leave the room, sister."

"Oh well," answers the sister. "Certainly he needn't have clambered out of bed with his plaster cast for that."

"What will you have then?" she inquires of me.

I am frightfully scared of the turn the conversation has taken and I have no notion at all how the things are termed professionally. The sister comes to my help by asking, "Small or large?"

I sweat like an ape and mumble in my confusion, "Oh well, a small one."

Well even this was somewhat lucky. I receive the bottle. After a few hours I was no longer the only one and by morning we had all become accustomed to require without any shame that which we needed.

Now it must be made clear that this modesty of the man rested on a false presupposition for the distinguished and high-born nurses as well as the professionals who in no way shared these feelings. On the contrary, they were frequently led into the hospital by desires which had a very definitely libidinous coloring-to observe closely the intimate details of the male organism. An Austrian soldier has made the following note in his war diary:

"It is quite undescribable how the ladies who receive the wounded at the station in G- acted toward us. For the most part we were in a horrible condition, shot up and just worn out completely by the journey and among us there was one comrade who had to have a leg amputated at once. Very frequently these women would insist that we undress although it wasn't necessary. Every two minutes we were asked whether we didn't have to satisfy any needs. Of course we had our own opinion on that subject but we were too tired to complain or to contradict."

In the most splendid of all war books Karl Kraus has one of the regimental physicians of the Austrian army and his colleague have the following conversation which is relevant to our theme:

The regimental physician: "Yesterday we had an awful day at the hospital. The nurse Adele has an enormous fear of me and she dropped the bed-pan of a Bosnian soldier. You should have seen the great merriment the others derived from this until I came by. Of course the women must be impressed. But yesterday at all events we had a great day."

The colleague: "The same conditions obtain among us. The greed of these aristocratic women is quite incomprehensible to me. The others serve in the linen rooms, pantries and so forth, but the aristocrats desire nothing more or less than service with the bed- pans."

The regimental physician: "I must confess that at the beginning I was intrigued to see such fine girls doing such work. But one becomes dulled to such matters. I wondered to myself, 'Why do they do it?' For patriotism and so forth. But where have I read that we, the physicians, should be against it because the shock which the female nervous system derives eventually makes nurses entirely unfit for marriage. It is a problem, but one would be insane to worry about problems during the war."

Again we have the report of Lieutenant Feder who was captured by the French. He asserted that when at a certain station he desired to visit the privy, the ladies of the Red Cross who were accompanying the soldiers demanded that the door remain open and all these women observed him as he performed these natural functions.

Numerous similar stories are told concerning French ladies of the best social circles which may be accounted for partially by the unconcern of the French in these matters. One need think only of the public privies in the Parisian streets in which the man can quietly perform his functions while the tipper portion of his body can stick out from a narrow aperture and continue undisturbed his conversation with the woman standing nearby. Masson, in the book already mentioned, has established this coprolagic pleasure in French women during the war.

Not only is it certain that the motives which drew many women, especially of the better classes, to nursing are difficult to explain without the point of view of the psychopathia sexualis but conversely that the moralizing influence, which this altruistic profession was expected to exert upon the men were for the most part quite unrealized during the World War. In his frequently quoted book Eberhard has cited the following statement of the superintendent of nurses in a hospital which had originally appeared in the Deutscher Evangelische Frauenzeitung:

"No one who has not been a nurse knows to how many moral dangers she is exposed. Nursing as such does not entail or exercise any exalting influence just because certain pious and noble women have manifested devotion and love to their neighbors. It has been assumed fallaciously that it was such service which made these women noble but this is not the case; the reverse is rather true. For example, the danger of a nurse becoming hard and dull is very large and real; unfortunately in all organizations there are nurses who have become hard and callous. And nobody has a finer appreciation of this condition of the nurse than the patient himself who, as a result of his physical pains and weakness, has become a more sensitive person than the healthy man. Furthermore, in the mental and physical defenselessness of the patient there is the temptation that the nurse will involuntarily seek to abuse her unconditional power and exercise an intolerable tyranny over the sick. But of course the greatest danger of all lies in the care of men and in the continuous intercourse with the young physicians. All these dangers increased enormously during the war. There are extant numerous proofs of the misuse of the nurse's authority. In the anonymous German novel of the war called Hagen Im Weltkrieg there is an interesting conversation between two soldiers at the front who have very depressing things to relate concerning this particular matter. Thus one relates the following:

"'I am talking against the whole system to which the soldier is exposed, the soldier whose highest duty and honor lies in his obedience. Now, take for example, the examinations, in the examining room of the Red Cross nurses. I think that it is a real shame. I myself have been in the psychopathic department of a garrison hospital where the soldiers had to stand in line naked and wait for the physician, while three young geese in nurses' clothing continually went to and fro bearing a certain very significant smile on their impudent little faces. It is an unheard of thing that immature girls, ministers' daughters and that sort of people, who at home and school were taught that nakedness is a sin, should be asking the soldiers whether they have a venereal disease and if so where they got it, and in certain cases even actually taking a specimen. This is especially strange considering the fact that our culture is so very prudish and that our ministers, for example, go into such a huff whenever they see statues of naked people. Or take, for example, another experience that I had where a certain lady had a job as a secretary to a physician. Among her duties she had to prepare the patients (psychopaths) for examination and even to assist in the actual examination in which the psychotics had to pull up their shirts and expose their private parts. One can understand how her chaste sensibilities were prostituted and grossly abused in this procedure. If conditions were reversed then every paper would be full of outcries against the immorality. Finally, I might say, that I was present when nurses made their rounds with the visiting physicians in the venereal wards and did things which the mass of orderlies standing around could just as well have done.”

The superintendent, Margot von Bonin, whom Eberhard has quoted, did not mention certain other dangers which the female nursing corps was exposed to and which, from the standpoint of bourgeois morality, must appear very considerable indeed. Insofar as these hazards issued in a greater erotic freedom for the nurses, we believe that we can attribute that freedom to the material independence which these women derived from their profession. We omit at this point any consideration of the escapades between nurses and soldiers-a matter with which the chronique scandaleuse of the war years was filled to overflowing. They are scarcely to be considered as anything other than a natural consequence of woman's active participation in a profession-a phenomenon which finds its parallel in the life of women active in other vocations. Everywhere material independence goes hand in hand with a freer conception of sexual morality so that we can not believe that the nurse's way of life has anything particularly symptomatic about it. The most that we can say is that the great pleasure which accompanied the composition and narration of these scandalous stories during the war was rather symptomatic of the pathologically increased erotic interest of the time.

During the war there was a popular song current in Hungary concerning the more than doubtful reputation of the nurses. Objectively it can be said that this bad reputation was shared by all categories of nurses from the kitchen personnel to the Red Cross nurses, deaconesses and even Catholic sisters. Of course there are no statistics by the aid of which we can control these assertions. One fact must not be overlooked in this connection-that among the nurses there were a not inconsiderable portion of erstwhile prostitutes. Thus in the cities of the north of France, especially in Calais, formal raids had to be carried out among the thousands of Belgian women who streamed across the French border after the capture of Antwerp by the Germans. These raids were not so much concerned with the finding of women spies as with the elimination of certain girls who had been street-walkers in Brussels and Antwerp and were now continuing their maneuvers in the populous little cities of northern France; only now they wore the simple black and white garb of the nurse.

It was notorious that a great number of prostitutes dressed as nurses were functioning behind the Russian front and even in the scene of operations. In Berlin, as Iwan Bloch reported, at a physicians' meeting shortly after the war, a considerable number of prostitutes under the mask of nurses were arrested by the police. To weaken his allegations somewhat Iwan Bloch reminded his audience that in peace times also the raiment of the nurse had frequently been employed by prostitutes. In a German legal paper for 1915 we find a statement of the Chief Justice Stendahl concerning the protection of the nurses' garb which was so frequently being abused. The complaint was there made that very frequently people would appear in this outfit who certainly were pursuing very different ends from what their professional uniforms entitled them to perform. All sorts of commercial and swindling practices were abetted during the war period by the employment of this outfit. Thus a certain publishing firm distributed its productions of a rather frivolous nature through sixty girls who went from house to house dressed in nurses' uniforms.

It may be advisable, in considering the erotic determinants of nursing, to distinguish between cases in which this activity was a means to an end and such to which it was an end in itself. In the first case, where the nurse conserved her activity as being a road to a definite goal, this goal can be said to have been an erotic one. Thus many a girl, who before the war was for one reason or another unable to achieve the happiness of a good bourgeois marriage, was impelled by the hope of, getting a man more easily as a result of her nursing activities. And, as a matter of fact, this did actually happen in a great number of cases. Nevertheless it was this fact which to some extent contributed to the evil reputation of the nurses.

During the years of the war many stories were current concerning the self-sacrificing care and devotion which the nurses expended upon the wounded, 'the love which developed in the ensuing convalescence between the grateful young soldier and the woman rejoicing in her opportunity to be of service, the whole episode finally culminating in marriage. However, as a matter of fact, these stories very frequently had quite a different ending. Far more numerous were the number of these instances where the nurse saw all her devotion and love and self-sacrifice misused, rejected and abandoned. Many a nurse was deceived in her calculation of nursing activity as a bridge to marriage. It may be that there were numerous cases of the sort reported by a soldier at the front who described at great length the suicide of a nurse whose offer of marriage had been rejected by an officer after he had had intimate relations with her.

This soldier had been part of the corps that had buried this unhappy woman at the military cemetery at Guise. It seems to us that this case is more or less typical and that numerous other cases of this sort happened not only at the front but also in the hinterland. For those women also who hoped to achieve more suitable conditions for the seizure of a bit of love the profession of nursing was a means to an erotic end. We are concerned in this case for the most part with virgins or spinsters, half or totally withered, for whom the hospital filled with men of all sorts was an incomparable opportunity. In his novel, Pastor's Anna, Henel has given us a picture of the motives that impelled an exceedingly strait-laced daughter of the pastor of a city in eastern Prussia to become a nurse. He points out there that the elderly maiden, who otherwise would have dared only to indulge in silent and tearful dreams concerning the appearance and form of a man, was now working at a surgical station in the most delicate situations and without any qualm or hesitation was manipulating naked male bodies. Of course there was a certain amount of bravery attached to working at this war station but at the same time it afforded her a certain satisfaction. She thought less that war was dreadful because it could inflict horrible wounds, and much more of the fact that it permitted women to come into contact with so many men without flinching at all.

In those cases where the care of the wounded was an end in itself the selflessness and self-sacrifice quality of many magnanimous women bore very noteworthy fruits. Of course there was no lack of heroic deeds among these women which contributed considerably to the construction of legends concerning these nurses. But while we will admit this fact and do not abate one iota of respect for these contributions, nevertheless we want to take a little more time to investigate the sexual-psychological side of the problem; we therefore avoid giving any statistical estimates concerning the number of cases in which pure love of humanity or genuine patriotism can be regarded as sufficient motives.

There is an amazing amount of proof to establish the fact that the care of the sick was not only a means but also an end in itself in the vast number of cases colored with a very libidinous streak. Protagonists of the theory that in woman all the expressions of life are far more deeply rooted and anchored in sexuality than in man, may find in such cases support for their position. Without taking sides in this question we will just let some of these cases speak for themselves. In Dr. Wilhelm Steckel's outstanding book, Psychosexueller Infantilismus, which contains a very rich collection of case histories, we find the following assertion:

"A very interesting narcissistic type is constituted by those people who just can't bear to see the happiness of other people in their presence. These abnormal individuals want to mean something, want to do something for others, want to help them, want to console them, want to expend love upon them. These narcissists love only themselves but they are enamored of the position of the love-expender or the love distributor. During the war I could observe numerous examples of this type among the nurses.... The following is an example of this condition. A very intelligent nurse has given me the following description of her condition: 'I am forty-eight years old and I can very calmly confess to you that there is no joy as great for me as the sight of gratitude in the eyes of a man whom I am nursing. This joy is like an intoxication. It is the only orgasm which I have been able to feel in life. Love I have never desired but I have always yearned for gratitude.... I have had numerous relationships but I have always given myself out of pity and out of a feeling that the man might be made happy. I confess, too, that I am proud, even vain of my talent as a nurse. I want to be loved and admired by the patients. I want to pass through the ward like a mild and generous fairy expending love and conferring happiness."'

In addition we find in the relevant literature ample proof for the inordinate or abnormal desire on the part of the nurse for seeing sexually flavored spectacles, and also for a certain voyeur condition with mysoophilic components, as well as a certain sadistic nuance in their activity. A splendid presentation of all these factors has been given by, perhaps, the best student of this question, the French physician, Dr. Huot. Concerning his nurses he has written the following:

"In the rather modest circle of activity which was alloted to them, their eagerness for fire made insatiable demands that were only satisfied when they had one transport of wounded after another and they were sad and jealous when the nearby service station had more customers than they. Even more significant is the attraction exercised upon all alike by the tragedy-laden atmosphere of the operating room. It was their highest desire to attend operations and in this they were absolutely blind and deaf to the worst sort of impacts upon their senses, the groans of the wounded, the moans of agony, they never for a moment lost their cold-bloodedness or skill. With equal passion these young women and girls gave themselves to the bandaging of the most frightful wounds and the most grievously wounded without shuddering at a single contact with the most disgusting and exciting circumstances. It is very difficult to reconcile this devotion of the nurses to the wounded and especially the grievously wounded, with the legend of the weakness and over-susceptibility of women. I may be permitted to recall that a very significant personality has used in this connection the word sadism. Modesty forbids me to say anything in contradiction that has come from so distinguished a quarter. Nevertheless, I would rather see in this an expression of that tendency of the French women which is directed with all possible energy against the unsatisfying reputation of the 'weak’ sex which they regard as extremely annoying and undesirable.... But still another point must be emphasized - that mysterious feeling, that somewhat perverse disturbance which, when it arises, stirs up certain women with the prickling compulsion of a physical desire and impels them against their will to seek a nervous excitation which they have never yet felt and which they hope to find in the odor of blood and in the sight and touch of palpitating male flesh. Perhaps this is the best point to say something concerning the oft-mentioned connection between female sadism and war. From another side too, the thesis is supported that the hyper-activity induced by the war, with the resulting uninterrupted strain of the nerves, called forth in many women with a predisposition for that sort of thing, a higher irritability of the reproductive centers which always reacts so promptly to the foremost considerations of the organic disturbance. This fact appears to me to be undeniable in respect to the civil female population at the front-a consideration of whom from this standpoint is especially interesting."

Aside from the great excitement induced by the continuous pressure of danger and of the thundering of the cannonade, it appeared as though the irritating smoke of the constant shooting which had settled down upon all the cities and villages adjacent to the firing line had filled them with a certain fluid, with a certain intoxicating poison which set these women into a state of tremendous excitement. In one of our most beautiful places the female population made the most violent and passionate protest against the removal of a certain division of soldiers and flooded the military authorities with reproaches, and nearly rioted to keep these soldiers within their own walls. We might recall the case of the young lady of Rheims whose violent amorous ecstasy was one night disturbed by a terrific bombardment. The ardent young woman would by no means desist from her activity and insisted upon completing the amorous process, clinging almost insanely to her partner so that he could scarcely breathe; he had to use all his power to free himself from this woman and fled to a cellar. The odd fact that the nature of war atrocities and bloody deeds have an erotic effect upon women was made long before the war and was merely confirmed during it. Throughout the war there were many parallels to the execution of Damiens reported by Casanova, which the ladies of Paris observed from their windows in a veritable paroxysm of erotic delight and amused themselves throughout the day with the most terrific suffering of the poor tortured creature. And while we refuse to believe entirely the tales of German prisoners-of-war of being insulted, abused and manhandled by women during their journey through Paris and other French cities, we can very well believe that certain of these sadistic excesse~as exposure of the rear portion, spitting on them, manhandling them with sticks and umbrellas, etc.-may very well have occurred.

There is one more question to be answered: how the men, especially the patients, reacted to the excitements and lusts of the nurses. We have already seen that corresponding to the voyeuses, the soldier manifested a definite modesty, or, as we might more correctly say, a lack of correlative exhibitionism.

During the war years public opinion treated the nurses nearly always from the erotic point of view but in a thoroughly ambivalent fashion. On the one hand the transfigured form of the nurse was put in the center of every idealistic cult which was nevertheless thoroughly libidinous; and on the other side it seemed that a special pleasure was taken in besmirching this ideal figure, of attributing all her activities to thoroughly erotic motives in a much more comprehensive way than anything we have here attempted. In general the impression created was that the nurse had to be either an angel or a whore. That the evil reputation proved itself in general to be stronger than the idealizing tendency is partly due to the physicians who in general had a very derogatory opinion concerning their female help. In the dialogue of the two Austrian physicians quoted above from Karl Kraus's novel the nurses are called simply Weiber (women), which corresponds quite well to the general practice during the World War. Even the common soldiers had but little more respect for the sisters, an attitude which all the propaganda in behalf of the nurses at home could not alter. It is not impossible that one of the motives for this disrespect was a kind of erotic jealousy, for in a number of respects the conduct of the great number of these nurses was not such as to call forth the sympathies of the ordinary soldier. Any soldier who had ever been at the front knew that the nurses adored the officers, that in many cases they openly showed that they felt themselves above the common patient, by a class-consciousness that was quite unfounded, feeling themselves to be in the same class as the officers. What was worse everybody knew about the amours of the nurses which most frequently were carried on with the officers rather than with the common men.

The sadistic pleasure of the nurses in drastic excitations of the senses, of which service in the hospital offered more than enough, enables us to understand the desire of many nurses to get as near to the firing line as possible. That this tendency was not something accidental, but somewhat more or less symptomatic of the times can be gathered from a number of similar reports. Thus Professor Hohenegg of Vienna wrote that a great portion of the volunteer nurses requested service at the front and Dr. Huot was able to report the same conditions concerning his nurses who had already been through the fire. "Among many," he said, "who had been placed in an erethic condition by the continual bombardment, the wish became very strong to serve in the very front line.... And how these nurses cursed their sex which prohibited them from sharing dangers and fame by the side of the men, and their inability to be admitted to the actual scene of operations in the same way as men."

Actually it happened repeatedly during the war that nurses would spend some time on the very front line of battle. Thus a few women, most of Hungarian descent, spent weeks in the trenches with the Austrian army. Then too the English nurses had a weakness for being photographed with the bullets whistling around their ears and not in artistic or womanly costume, but in the military khaki. Of course the danger to these women was in no way as great as that of the French, Galician and Belgian women who had remained home and who had permitted themselves to be buried under the ruins of their houses.

From French sources we know of one case where an English nurse spent considerable time at the firing line. An officer of the French general staff, who had had the pleasure to dine with her at the table of the Belgian ambassador, M. de Broquer, reported that this girl was the charming daughter of Lord F. She had spent five months on the front line as nurse. In all this period she had stayed quite close to the trenches in order to get to the sick at once and to nurse them. She was a very striking figure in her khaki, yellow boots and military cap. And she was just as gracious as she was pretty and hence her value was recognized on the whole northern front where she took part in the battles of the Yser, and also near Dixmude. Her favorites were the marines. It was most delightful to hear her prattle argot with her English accent. "J'aime heaucoup ces petits fusiliers: il savez tres bien zigouiller les Boches! " The following case deserves some consideration. When the Germans captured a detachment of Russians near the Narvic Sea they found among their prisoners a uniformed nurse of about nineteen attired in male costume. When she was asked why she was fighting at the side of the men instead of serving as a nurse, the young lady replied that in Russia the nurses had a very evil reputation and hence she preferred to put on a uniform. Another Russian nurse by the name of Iwanova is said to have participated in a certain bitter battle on the northwestern front, and when all of the officers had fallen she rallied the retreating. soldiers at the decisive moment, gave them new courage and stormed an enemy trench. She died pierced through by a bullet and received posthumously the George cross. The French press extolled her as a heroine whereas the Germans branded her deed as a crime against the law of nations.

In other cases too we find women on the firing line and even in trenches, particularly on the Western Front. According to responsible reports, in 1915 the German soldiers on this front frequently heard dance music issuing from the French lines or from the little settlements behind the firing lines. Other circumstances make it appear that occasionally women came to the front. Thus actresses from Paris or other French cities spent some time in the vicinity of the front after it was realized that the war was to last longer than expected. These visits by actresses appear to have been quite frequent in the Austrian war theater. In the novel, Soldaten Marien, the author depicts vividly the erotic effects which the presence of a singer in the Russian trenches exercised upon the German soldiers on the other side. "All waited for the miracle which came late at night. The voice began to sing again-that strange woman's voice on the Russian side began to sing again. Slowly and gently she sang again and again. All the soldiers felt their hearts in their throats. Could so much sweetness reside in one woman's voice.... Barfelde was no longer leaning against the tree. He stood and pressed his hands together. How beautiful this woman ought to be! He saw her, her sorrowful eyes and sweet red mouth..."

Occasionally too visits of a family to the front took place. Thus an Austrian officer has informed us that in 1915 there came to his station directly behind the front line a strikingly pretty and elegantly clad lady who requested permission to visit her husband, an active Austrian lieutenant who was then on the firing line. When the lady, a typical wife of an Austrian officer, was asked why she had such a peculiar desire, she voluntarily informed the commander that a slight accident had befallen her at home. Her effervescent temperament had led her to commit an error which had not remained without its consequences; by meeting with her husband now she desired to legitimize that unpredictable sequel of her ardor. She received the necessary permission, thereby eradicating an impending tragedy.

During the war French newspapers printed the report of a French soldier serving in the field of battle concerning the visit to the front line of a French woman from Brittany. "One could scarcely imagine how much energy was locked up in such a little woman. She came from the farthest corner of Brittany in order to place into the arms of her husband a child who had been born after his departure. She had sworn that he would just have to see his child. The thought that he might die without seeing it had tortured her brain; and so one fine day she set out on her journey. She overcame all hindrances, slipped by all guards and finally got to the trenches. One evening we were washing our dishes and were preparing the straw for our beds when one of our comrades let out a yell, 'My Louise!' It was she. Without a word she put into his arms the little baby wrapped all in white. He scarcely dared to kiss it. And as for us, many of us have seen exciting spectacles during the war but nothing like this. Many wept. He, the father, was pale and speechless as though a gentle bullet had bored through his heart."

Finally on certain occasions women were forced into the dangers of war against their will and compelled to render some form of service that happened to be necessary.

Thus in 1918 many manual workers were driven into the very trenches on the southwest Austrian front and suffered many casualties.

The question of female soldiers during the World War - of the voluntary participation in the war by women - we shall treat in a later chapter.