Great War Great Escapes

Giving the Enemy the Slip

from 'The War Illustrated"

MY FIRST ESCAPE FROM RUHLEBEN

WALLACE ELLISON

I first thought seriously of escaping from Germany when I found myself in the Stadt Vogtel Prison, Berlin, in the spring of 1915. I had played with the idea before, but the difficulties in the way seemed at first almost insuperable. I was interned, along with other Englishmen living in Germany, In Ruhleben Camp, which is situated between Berlin and Spandan, more than three hundred miles, as the crow flies, from the Dutch frontier.

Once ideas had begun to take definite shape in my mind, I lived only for the moment when I could put them into execution. I thrilled at the prospect as a boy thrills at the thought of his first love. Sweet, indeed, are the uses of adversity.

Now all this rendered necessary a fairly thorough knowledge of conditions in Germany beyond the last barbed wire fence of the camp, and this knowledge could only be arrived at by dint of much patient and cautious inquiry. A chauffeur in camp lent me a Michelin guide-book, which proved to be a great boon, and although little detail was given, one was able to get a fairly good idea of the general nature of the country through which one might have to pass. Much was also learned from conversations in camp, though a good deal of the information obtained in this way proved to be of very little practical value. The most valuable information was obtained by casually chatting with those of our German guards who had recently returned from leave, and it was a great opportunity to get into touch with a soldier who, while on leave, had travelled in the direction of the Dutch frontier. Such a man, when questioned in an innocent manner, was often able to clear up such doubtful points as strictness or laxity of control by detectives on long-distance trains travelling in the direction of the frontier.

Had I taken advantage of the few little privileges granted me as barrack captain I should doubtless have found it easier to escape from Ruhleben Camp than I could as an ordinary interned prisoner. Feeling, however, that it would not be playing the game to make a wrong use of these privileges, I decided to abandon my intention to escape as long as I remained in that position.

In April, 1915, when I ventured to oppose the German camp officers on what I regarded - and still regard- as an important matter of principle, I was informed by Baron von Taube, the Commandant of the camp, that I was being taken to prison for the purpose of trial. Two corporals, armed with rifles, escorted me to Berlin, and handed me over to the warders of the Stadt Vogtei Prison. The prison authorities were informed later that I had been sent "for punishment" - not for trial - and that I had to be kept in the strictest form of solitary confinement for an indefinite period. All my letters of inquiry and of protest remained unanswered.

While in the prison yard one day for exercise, I met a Scotsman, Henry Kirkpatrick, originally from Dumfries, and chief engineer of the Union Cold Storage Co., Ltd. He had just arrived in prison after having made a very plucky escape from Rubleben a fortnight before. Although fifty-two years of age, he had been the first among four thousand men to attempt to escape from Ruhleben and after a veiy adventurous fourteen days' tramp had somehow or other become separated from his companion, who spoke perfect colloquial German. At this stage of his adventures he was only about thirty miles from the Dutch frontier, and the previous night had fainted from exhaustion in front of an inn in a small village. He recovered and pressed on, however, before any one saw him, but in passing through the outskirts of Cloppenburg the following morning he was overtaken by a gendarme on a bicycle and at once arrested.

A lasting friendship grew up between us. Our cells were on the same level on two sides of a corner, and we would frequently whistle to each other, climb up behind the bars of our windows, and hold long surreptitious conversations condoling with each other about our poor empty stomachs, and through the iron bars discuss the details of his escape. I learned much from him of conditions in Berlin and Germany from an escaper's point of view.

At the end of my five weeks' detention I bade farewell to Kirkpatrick. The American Embassy had succeeded in pro-curing my release from prison, and I was sent back to camp.

It was still winter when I was sent to prison, but when the day of my release came it was already spring. A Berlin policeman -escorted me from the prison by train through Charlottenburg to Spandau and Ruhieben, and I remember vividly his amazement as he contemplated my childish delight at the sight of fresh green grass and the luscious green of budding trees. I cannot remember sheer force of contrast ever having touched my senses with such feelings of delight, unless it be that supreme moment when, on the night of November 13, 1917, I waded through the last frontier canal, and climbed, a free man, on to neutral soil at the other side.

Two of my friends in camp were Mr. E. Falk and Mr. Geoffrey Pyke, whose plucky escape from Ruhleben Camp has been recorded in Blackwood's Magazrne and in Mr. Pyke's book To Ruhleben and Back. For a time we were practically pledged to each other to escape together. We met at all hours of the day, and in all sorts of places in camp, for the purpose of discussing plans and consulting maps and newspapers.

For a long time the question of greatest importance was that of choosing the most suitable route. We ruled the Swiss frontier, both in Austria and Germany, out of the question, partly on account of the great distance which would have to be covered in order to get there, and partly because we had very little in- formation concerning either of these two frontiers. The two others which remained were the routes to Denmark and to Holland. The route to Denmark by land, had we chosen it, would have meant covering almost as much distance as that from Berlin to the Dutch frontier, and, further, presented two definite objections. The first was the difficulty of crossing the Kiel Canal, and the second was the presence in Schleswig-Holstein, at that time, of a very considerable number of German troops. The frontier was, moreover, only a short one, and comparatively easy to guard. The prospect, on the other hand, of escaping by boat across the Baltic to Denmark appealed very strongly to us, and it was long before we decided to abandon this idea and centre all our thoughts on plans for reaching the Dutch frontier.

Our idea, had we chosen the northern route, was to have tramped the whole distance to the Baltic coast, lying up during the day and walking only by night. On arrival there we should have endeavoured to evade the vigilance of the coastguards, steal a fishing-boat, and row or sail across the narrow straits which separate Denmark from Germany to the north of the small peninsula known as the Zingst. The danger of arriving on the coast, however, and finding it impossible when there to procure a boat of any kind, led us to rule the Danish route out of our reckoning.

When the date of our departure was drawing near I had a strong presentiment - I can give it no more definite name that three were one too many for such an enterprise, and I decided spent about a fortnight to drop out. My two friends escaped in July 1915. When I look back on their success and on my failure at the time, I do not regret my decision, for, after all, it was infinitely better that two out of three should escape rather than that three should be captured.

As soon as they had gone l set to work on fresh plans along with another man who lived in the same horse-box - a British subject by naturalisation, who spoke perfect German and had a thorough knowledge of the country and the ways of the German people. I had not at that time a thorough knowledge of German, and my accent was quite pronouncedly an English one. From this point of view, my companion, with his perfect German, made an admirable second. His skill in conducting the most delicate negotiations drew from me unstinted admiration. Often he went to parlous lengths. He had a very winning way with the German guards, and, not lacking funds, soon procured one or two willing helpers among them. I expressed strong disapproval from time to time, but he had always such excel en reasons and was so confident of success that I ended by holding my tongue and giving him a free hand. We were taking time by the forelock and making sure of the German indemnity-in services rendered.

After our recapture - for we were recaptured - we strongly and most indignantly denied that we had bribed any one. Now that the military power of Germany has been broken, I can admit that we had-in fact, we bribed several German soldiers, and, so slippery is the path of wrong-doing, I think we should have bribed the Commandant himself if we had thought he would have accepted our bribe, and, most important of all, if we had thought that we would get value for our money.

Our plan of escape gradually grew into a triumph of perfect organisation. My frien4, in his implicit belief in the almighty Mark, bribed to get money brought into the camp; bribed to get things which we should need on our journey smuggled out of camp to addresses in Berlin where we could pick them up; bribed to have things brought into camp - in fact, bribery became the order of the day. My qualms of conscience eventually disappeared entirely, and I came to look upon it all as a matter of course. By further largesse he almost succeeded in making our escape a kind of personally conducted Cook's or Polytechnic tour; and I think he would be the first to admit, now that the war is a thing of the past, that his unlimited belief in the efficacy of money , at the last moment, to our undoing.

To my amazement, he succeeded in working up friendly relations with an enemy soldier in the camp, whose brother, the soldier said, was a horse-dealer. I met the brother later, and should say he was probably a horse-stealer. In any event, he was reputed to have a fairly intimate knowledge of frontier conditions, and the soldier claimed that his brother had several times brought horses and cattle from Holland over the Dutch frontier into Germany. One part of the Dutch frontier he claimed to know particularly well, and E bribed the soldier to arrange terms with the brother for a personally conducted tour from Berlin to Holland. The brother was agreeable, on terms, and it was not long before E had the whole scheme complete. Our scoundrel of a guard also undertook, for a further consideration, to be instrumental in allowing us to escape from the camp.

I lived, along with my companion and three others, in a horse-box in Stable No.4, and it was usual for the corporal and soldier in charge of our barrack to come round at bed-time and count the inmates of each box. About a fortnight prior to our escape, E threw a mosquito-net over his bed each night when he went to sleep, and I fixed a curtain on a wire in front of my bunk. The two of us made a pretence of slipping into bed, dressed or undressed, when we heard the corporal begin his round; I drew my curtain, E let down his mosquito-net, and when the corporal and soldier arrived to count us, one of our box-mates whispered: "They are both in bed."

This we kept up for a fortnight, and as the idea of either of us attempting to escape had not entered the corporal's mind, he went away, night after night, quite satisfied. We concluded that we should in this way make sure of a long start before our escape from camp was discovered.

There was much to recommend the policy of attempting to reach the Dutch frontier by means of a short railway journey and a long tramp; but eventually we decided to make a quick dash for Holland, and had we not been captured on the Dutch frontier, we should have succeeded in reaching Holland and freedom within less than thirty-six hours. As a matter of fact, the day Falk and Pyke, who had been a fortnight on the way, succeeded in crossing the frontier, we, after a journey of less than twenty-four hours, were captured there. This would surely have been a record escape, in point of view of time.

In those days it was usual for volunteer working gangs to go out of Ruhleben dragging carts, accompanied by a German soldier, for the purpose of bringing into the camp manure, gravel, and soil for the camp gardens. As it was desirable for us to escape from camp in the early afternoon, so as to be able to leave Berlin that night, we were glad to avail ourselves of the opportunity of escaping with the help of one of these gangs. Good men and true were plentiful in a camp like Ruhleben, and it was the work of only a few hours to get together a working gang of men who could be trusted to see little and say less. A pretext was found for taking a cart out of the camp to get gravel for the camp gardens, and if there were any observant people close to the main gates about four o'clock on the afternoon of the 23rd July, 1915, they were probably astonished to see E and myself strenuously helping, for the first time, to drag a cart through the open gates into the road which ran past the front of the camp.

Fortunately for us, the sentry at the main gate and the sentry accompanying the cart neglected to count the men who passed through. Our first trip with the cart was to an open field which lay between the railway and the road running from Berlin to Spandau. Escape there proved to be entirely out of the question. The sentry was, of course, our own pet scoundrel, and in himself was no obstacle to our escape, but the presence of so many Englishmen close to the main road attracted the attention of a considerable number of passersby, including several German officers, who watched us very closely. Our movements, too, may have aroused some suspicion, for I saw a railway official dodge from bush to bush on the railway embankment and watch us very closely.

We started a complaint that the sort of soil we were getting was quite unsuitable for our purpose, and persuaded the sentry to allow us to load up with fresh soil in a field much more quietly situated on the other side of the camp. The whole time I kept as much in the background as possible, in order that the sentry might afterwards have an excuse for not having noticed our absence on the return of the rest of the party to camp. I confess that I felt the whole time most ill at ease. I knew the sentry was not to be trusted, and quite expected that he would betray us when we attempted to move away from the gang.

The road to the field we had in mind led along the fringe Of a wood at the eastern end of the camp, and then, taking a sharp turn to the left, passed over a small wooden bridge. When we reached the bridge my companion and I moved to the tail-end of the pa an as the men turned to the left to go over the bridge into the field we slowed down, and as soon as the cart was out of sight walked away at an easy pace in the opposite direction.

Our road led us past the electricity works and then on to the main road leading to Berlin. In accordance with our carefully considered plans, E was to do all the talking, and I had to speak only when absolutely compelled by questioning to do so. In fact, we had gone the length of smuggling into the camp an ear trumpet, by means of which I was to persuade people, while we were passing through Germany, that I was almost stone deaf. After a little consideration, however, we decided not to use it, as we felt that it might attract too much attention. We thought it better that I should dress and look as far as possible like a German student on holiday, and, to this end, the day before our escape I got the camp barber to shear off all my hair. In England I should have looked like a criminal; in Germany the ruse helped me to look like a German university student. To complete my costume I had bought a pair of round horn-rimmed spectacles and a so-called Schiller shirt.

When we had left the cart and the bridge about one hundred yards behind us I removed my glasses, put on the horn spectacles, turned the white collar of the German Schiller shirt which I was wearing so as to have it outside my jacket collar, altered the shape of my hat so as to make it look as German as possible, and turned down the bottoms of my trousers, which when turned up looked far too English in cut. If I did not look like a young German university student on holiday, I must certainly have looked like a cheerful lunatic who had just escaped from an asylum. However, we were experienced our first snatch of freedom we had known for many months. The experience had all the glory and freshness of a dream. Free!

We were walking along the main road leading to Berlin, still fairly close to the camp, when my friend whispered, "Look out,” and I saw, to my dismay, that the carriage which conveyed the German officers to and from the camp was approaching along the highroad. It passed us within a yard, but was save for the driver, who eyed us very closely, drove on. We jumped on to a tram at the Spandauer Bock, and while we were sitting at the back of the tram passed a German corporal from the camp, who, to our amusement, saluted my companion, doubtless in the belief that E was going to Berlin on special leave. A pretty girl had to stand while we were sitting, and I had sternly to repress a desire to offer her my seat. "Remember, you are now a German," I kept repeating to myself. On the way to the city we left the tram, caught a taxi, and drove to the centre of Berlin.

My friend, as behoves the leader of a personally conducted tour, had, of course, arranged for apartments in Berlin, and we instructed the taxi-driver to take us to the corner of a street fairly close to the house we wanted. We were quite well received there, and early that evening the soldier's brother arrived. His first desire was to get hold of the money we had promised him, and only then would he discuss further plans. We handed over the money, but found, to our chagrin, that he had only the most confused notions of the best method of procedure. In any event, it was clear that we had to leave Berlin that night and travel to Duisburg, Crefeld, and Geldern, a small village quite close to the Dutch frontier. He assured us that he knew the rest of the way, and hinted at arrangements which he had made on the spot with a sergeant among the frontier guards stationed at the village of Walbeck on the actual frontier line.

It all sounded very vague and unsatisfactory. He looked a scoundrel, and at a time when the overwhelming majority of Germans were fiercely patriotic he was willing to stoop to so dirty a business. This in itself did not concern or worry us, as we were bent on reaching Holland by hook or by crook. All this meant, however, that we could place very little confidence in him, and our realisation of this fact added to our vague sense of uneasiness. Before he left we decided on the train by which we should travel from the Friedrichstrasse station, he, of course, agreeing to travel in another part of the train as though he had no connection whatsoever with us.

We left that night by an express train from one of the main stations in Berlin-the Friedrichstrasse Bahnhof - and had doing so was not to travel in as great luxury as possible, but to avoid any possible control by detectives on the way; and we thought it much more likely that we should be able to do so, and at the same time avoid embarrassing questions from fellow-passengers, if we travelled by sleeper rather than second or third class. We were right in our conjecture. My friend, to whom I left all the talking on account of his perfect command of the language, left me in our compartment, and shortly afterwards came back and assured me that he had arranged everything satisfactorily with the guard. We travelled from Berlin, along the line which runs within about fifty yards of Ruhleben Camp, and laughed quietly to ourselves as we pictured the astonishment and chagrin of the authorities on their discovery of our escape the following day. The journey to Duisburg was uneventful. There we changed, travelled third-class to Crefeld, spent a little time in the town, and then bought tickets for Geldern, a small village which lies within an hour's walk of the Dutch frontier.

We had to run in order to catch our train at Crefeld, and arrived on the platform just as it was moving out. It was thus impossible for us to select a suitable compartment, and we were bundled into a third-class compartment, which, much to our dismay, contained a Prussian railway official and, among other passengers, a German soldier returning on leave from the Eastern front.

In Duisburg we had each bought a copy of the Kolnische Zeitung. My companion was very much afraid that my unsatisfactory German would betray me if I were drawn into conversation. He immediately opened his newspaper, glanced at the headlines, read on for a few minutes, and then, leaning over to me, shouted in my ear in German: Die Italiener kriegen wieder ihre Pruggel! " ("The Italians are getting it hot again !)

I nodded vacantly and went on reading my paper. He then fell to discussing the war and Germany's prospects with the Germans in the compartment.

From May I, 1917, to the end of the war a broad belt of territory on the German side of the Dutch frontier was declared Sperrgebiet (forbidden territory), and special passports were issued to persons authorised to travel there. German soldiers were on sentry duty night and day at all railway stations in this area, their duty being to examine the papers of all who passed through. In July, 1915, however, there was no military guard on the station at Geldern, and all that we had to fear was the vigilance of the railway officials and the prying eyes of German civilians.

It was about ten in the morning when we arrived at Geldern, and after we had passed out of the station our accomplice, the horse-dealer, joined us, and we set out to walk along the highroad in the direction of the village of Walbeck, which lies on the frontier itself. We passed quite a lot of German s9Idiers, some on bicycles, some driving, and some on foot, greeted them cheerily when they eyed us with suspicion, and passed on. In the sheer audacity of our plan lay our salvation. It evidently occurred to no one whom we met that any escaped prisoner would be so mad as to walk along a highroad leading to a frontier village, unabashed, in broad daylight.

On arrival at the first inn we skirted the village of Walbeck, and, after walking about a quarter of an hour through the fields found fairly good cover in a wood, alongside of which ran a deep country lane or cutting. As soon as we had settled upon our place of concealment until nightfall, our accomplice left us to go back to the village inn, as he said, to confirm arrangements for our safe crossing of the frontier with this German sergeant whom he professed to know. He promised to return within an hour.

There we lay among the tall fronds of bracken and dreamed of our home-coming. The silence of the countryside was unbroken save for the singing of birds, the occasional bark of a dog in some farmyard near, and the shrill voices of children at play. I was very happy, and felt absolutely certain of success. Hour after hour passed, but our accomplice did not return. When he did not put in an appearance I was very relieved, for I would not trust him. According to my calculations, we were about half an hour's walk from Holland and freedom, and I was looking eagerly forward to the final stretch, when we should break cover and start out together on the interesting work of dodging the armed guards who patrolled the frontier.

We learned from one of the soldiers who captured us later in the day that from our hiding-place we could almost have thrown a stone over into Holland.

We were not satisfied with our cover, as it was not sufficiently dense to conceal us from any one passing by. About one o'clock, therefore, we went deeper into the wood prospecting for better cover, and eventually found what we sought in a clump of bushes close to one edge of the wood, on the side farthest from where we had hidden in the morning. There we lay, listening and waiting. Sometimes we slept peacefully, only to be wakened by the rain which fell from time to time on to our upturned faces.

The failure of our accomplice to put in an appearance worried E much more than it affected me. After we had been in hiding for some time his genius for negotiation began to assert itself, and he expressed a confidence which amazed me in his ability to return to the village and literally arrange with some one to buy our way across into Holland. He became more and more restless, and did not agree with me that to take the last stretch as a pure adventure offered the best chance of success. It was simply a difference of opinion on a question of policy. He felt convinced that he was right, and I felt convinced, and still do, that I was right. At any other stage of the adventure the consequences of a conflict of opinion might not have been so serious, but at this critical stage perfect unanimity between us was essential. Each man had equal interests at stake, and each realised that neither had a right to dictate any course of action to the other. His desire was that we should both return to the village we had skirted that morning, and see what we could accomplish by negotiation. I protested, on the ground that the game already lay in our hands- that we had only to wait until nightfall, and then cautiously crawl across the belt of open country which lay between us and our goal, that we should be courting disaster if we entered a frontier village crowded with soldiers, and that we had tempted Providence sufficiently with our audacity up to that point. Our views were irreconcilable. He generously suggested that we should each go our own way. The offer was tempting in the extreme, but I recognised that it was largely due to his guidance and his knowledge of the country and the language that we had been able to get so far in so short a time, and I felt I should not be playing the game if I deserted him at that point. He left alone for the village about four in the afternoon, and, at his request, I returned to our former hiding-place in the wood, in order that he might more easily be able to find me on his return.

While he was away the rain came down steadily, and I spent most of my time cutting long fronds of bracken with which I endeavoured to construct a better hiding-place in a dry ditch. My feeling of absolute certainty that all would go well had given place to a sense of vague apprehension, and when E returned, looking breathless and very agitated, about three-quarters of an hour later, I felt convinced that the game was up.

He told me that he had seen the horse-dealer in the inn, but the latter had not returned to jis because he was quite clearly being watched with suspicion, that he had been roughly questioned by a gendarme regarding his presence so near the frontier, and that his papers had been examined. We also learned later that we had been seen by some peasant women while we were walking through the wood back to our first hiding-place, and the information they gave to the military authorities in the village led to our capture.

A last remnant of hope lingered in my heart that all would still go well with us, but before many minutes had passed the rude awakening came. A hefty German soldier dashed, apparently unarmed, through the hedge which separated us from the deep cutting, and came towards us. When about a dozen paces from us caution got the upper hand, and he turned, dashed back through the hedge, and leaped on to the high bank on the other side of the road. There he joined a young fellow, whom we had not noticed before, and, unleashing a police-dog, urged it to attack us. I got behind a tree with the intention of climbing it, when I noticed that the dog, instead of attacking us, was running round in search of rabbits, and there was apparently nothing to fear from that source.

The soldier then called out to us: “Who are you? Have you identification papers?”

We shouted, "Yes !” in order to gain time, and told him we would produce them as soon as he had put the dog again on leash. Eventually he did so, and we joined him in the lane, where my friend produced several German letters, but nothing that was able to satisfy the soldier. He told us that we should have to go to the Army Headquarters in the village of Walbeck. We had not gone many yards before we discovered that we were surrounded by German soldiers armed with rifles, some of whom had rushed up on foot, others on bicycles.

It was clear that the game was up, and we informed them that we were civilian Englishmen who had escaped the day before from Ruhleben Camp. We were then marched into the village.

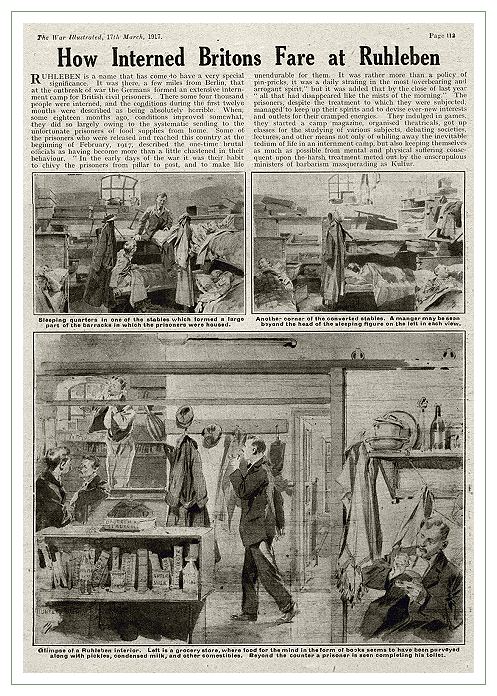

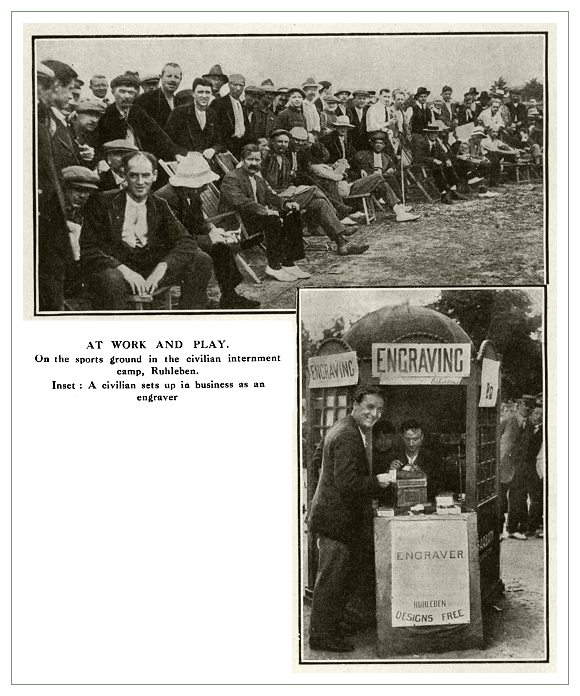

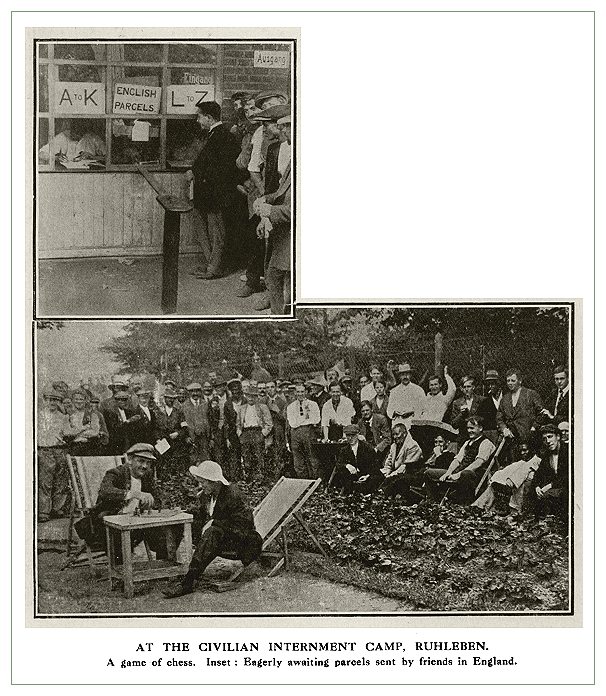

from the Times History of the War : photos of the camp at Ruhleben.