- from the newsmagazine

- 'TP's Journal'

- 'Great Deeds of the Great War'

- October 24, 1914

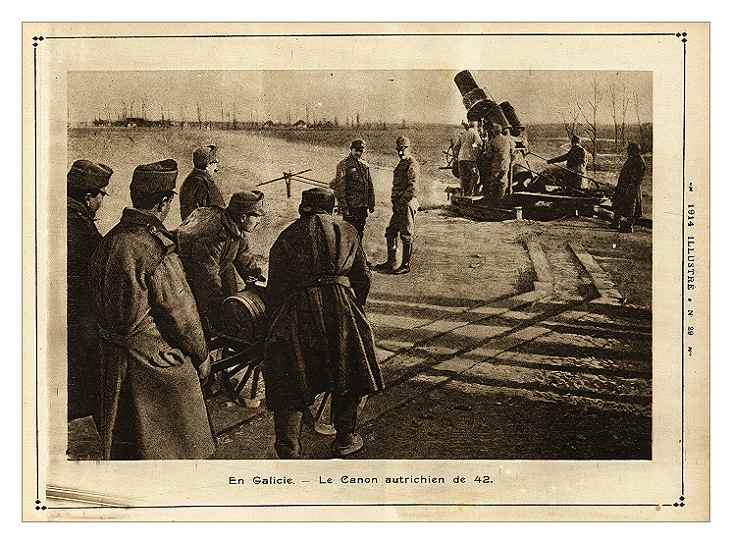

The German Goliath Gun

on the Galician front

The Goliath Gun That Conquered Antwerp

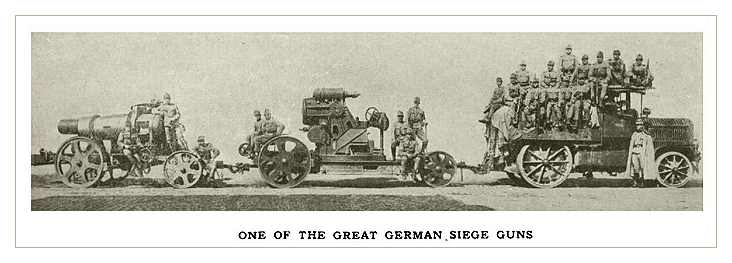

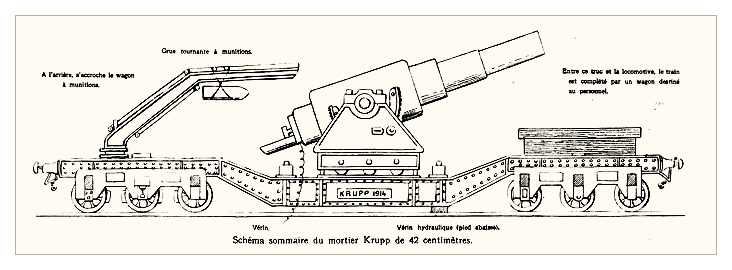

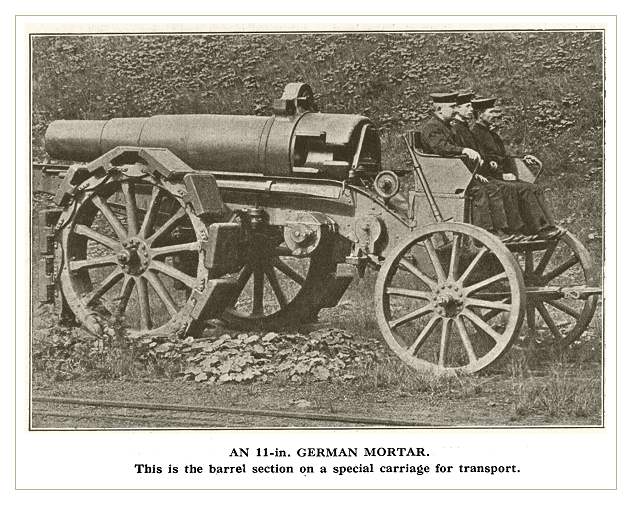

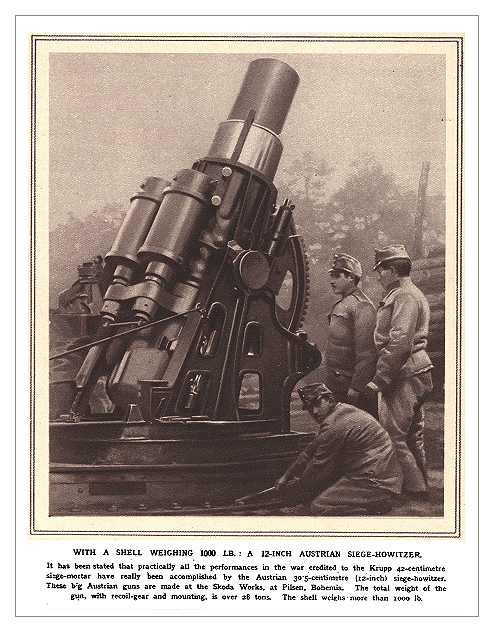

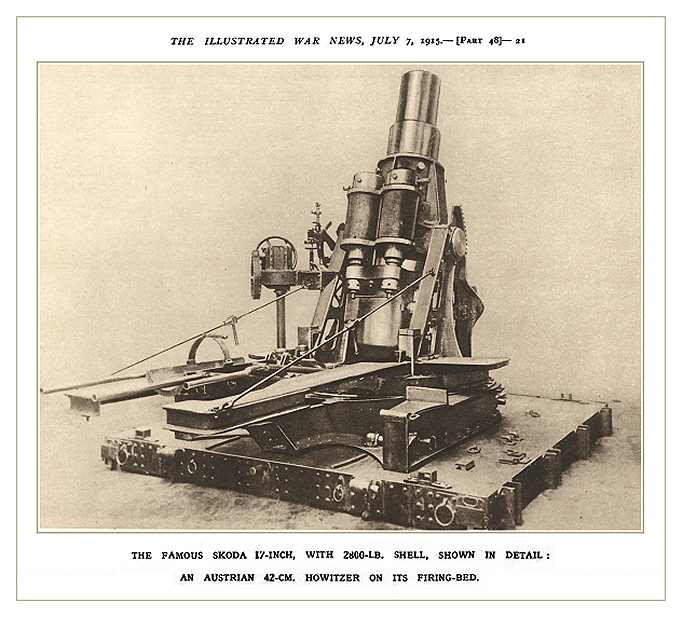

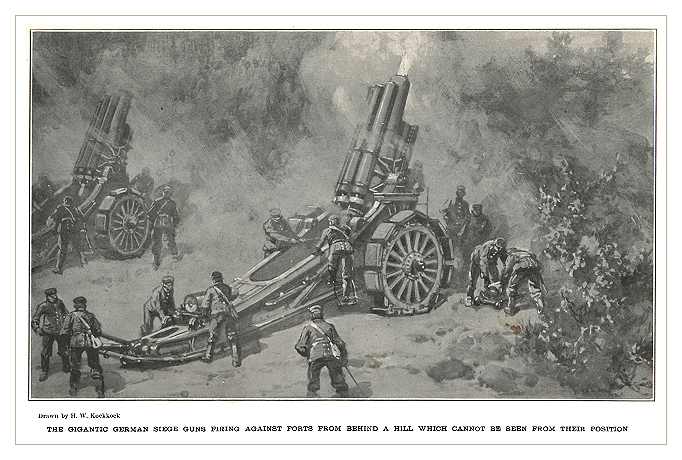

Mobile and Rail Transported Versions of the 42 cm Gun

The fall of Antwerp, considered by so many to be impregnable, after a siege of less than a dozen days, came as a surprise to most and as the fulfilment of prophecy to some. To all, however, the fall of the town made it apparent that the German army possessed a form of artillery so new and so powerful that few, if any, of the fortifications as planned on present lines, could hope to last against the terrific effect of its pounding. This artillery, it is known, was to be Germany's surprise in this war. It has certainly been a surprise, not so much because heavy artillery of the type of the new 16-inch howitzer should exist at all - for the events about Port Arthur in the Russo-Japanese war foreshadowed the employment of such pieces - but because of the ease with which these monster guns, weighing probably as much as 25 tons, have been brought up into position to face and attack fortifications.

Not a Novelty

The big gun is not a novelty; the Japanese used 11 inch howitzers before Port Arthur, and on our own battleships we have 15-inch guns. The big guns used by the Japanese, however, had to be transported with immense labour after their dismantling from the fortifications on the Japanese coast, and when they arrived in Manchuria they had to be set up on solid mountings bedded in concrete - a task of much effort and one taking considerable time. The great guns on our ships, apart from being of such construction and weight (about 100 tons) as to make them useless on land, gain most of their value from being built for the permanent platforms of shipboard. It is, therefore, not the heaviness but the mobility of the German siege artillery that gives it its value both in surprise and effect.

The Problem of Mobility

What these great 16 ½ inch howitzers are like nobody knows with any exactness, for nobody save their artillerymen and the engineers of Krupps have been able to see them in any detail; but we discover a great deal about them from another howitzer used by the Germans about which we know a great deal. This gun is another monster siege- piece, an 11-inch howitzer, a brute throwing a shell weighing 748 lbs. a maximum distance of six miles. This gun weighs 15 tons, and, as the Japanese found, it is a piece almost impossible to transport under usual conditions. The problem of getting such a piece from point to point with any degree of quickness and facility is a problem which has taxed the minds of gun constructors in war and out of war for a decade. It is the German engineers of the Krupp works who have solved it.

The Problem Solved

It was the dead weight of 15 or 25 tons that gave the task its supreme difficulty. Few wheels could stand the enormous dead strain, and few roads could support the passage of such a load. Moreover, the teams (61 horses) employed to drag the monsters would make the train too cumbersome for utility. The problem was solved by distributing the weight into manageable loads. The howitzers were divided into two parts, and carried on two separate vehicles. One of these wagons took the barrel and nothing else, and the other the mounting mechanism, the sighting and adjusting gears, the hydraulic and compressed-air chambers that take the shock of the immense recoil on firing, and the rest of the strong steel framework that supports the gun proper. Both carriages - in the case of the 11-inch piece, at least were fitted with "caterpillar wheels," that is wheels having a number of flat plates instead of tyres. These present a broad, flat surface to the road and prevent the wheel from sinking into soft ground. These plates also take off some of the shock of the howitzer when it is fired. Both carriages were to be drawn by powerful motor-tractors, which also carry the giant shells.

Putting the Gun Together

The problem of carriage was not the only one that the German engineers have surmounted. Having divided their gun into pieces, the trouble was to get it together again, a difficult task when not only quickness of handling may mean success or disaster, but when the guns are "platformed" in open country miles away from the nearest mechanical aid. This problem again was solved. Special guide-rails were built on to the carriage under the barrel, and a special system of wire hawsers and pulleys was fitted to both sections. When the artillery commander had chosen his battery site, the section holding the mounting gear was placed in position, the carriage holding the barrel was moved up into line with this, and the pulleys and hawsers set to work. So the monster barrel was drawn up between the recoil chambers, all parts were bolted home, and the monster stood ready to batter fortresses with its gigantic shells.

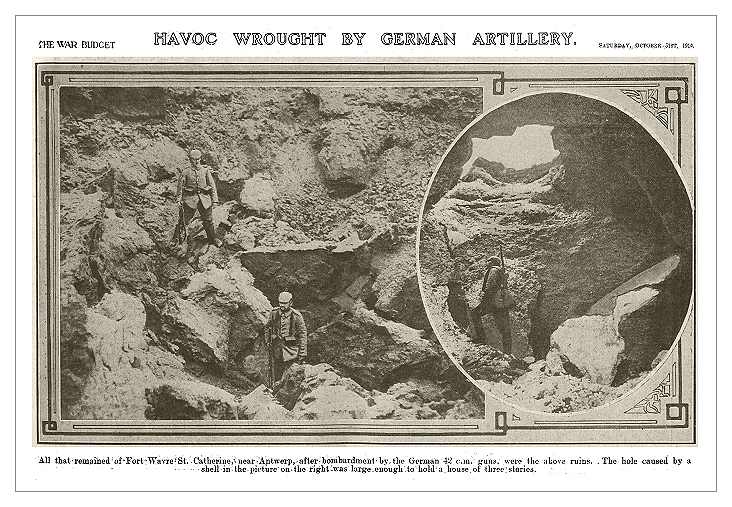

ruins of fort Sainte Catherine Wavre near Antwerp

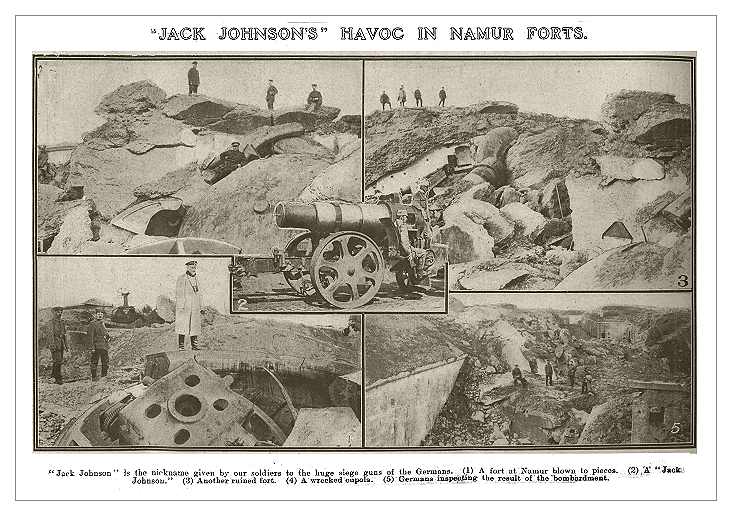

ruins of several Namur forts

The Terrible Effect

The effect of their terrible fire we have learnt not only from Antwerp, but also from Namur and partly from Liege. Antwerp's double ring of mound-like fortifications, though they are of solid concrete and tempered steel, were quite unable to withstand the awful impact of the shells. A few shells, some say four, some say a dozen, were enough to reduce the stoutest of these works to mere powder and to decimate utterly the garrison. The shells, dropping almost in a straight line from the sky on to the forts, have simply shattered them like egg-shells with the driving weight of the enormous blow, and the gases released by the tremendous detonation turned to dust everything that withstood its force. This much was proved by Namur, and this much Antwerp also proved. It was not necessary to have many of these guns in action; at Antwerp there seems to have been but two or four lit the most. All that is necessary is to concentrate the deadly fire of one-ton shells, each strike with a 5,000 foot-ton energy, on to a single fort until at fort is reduced to ruin, and then to take one's time and concentrate on another. At Antwerp the Germans reduced one fort in this way, and through the gap thus caused poured forward, unimpeded by the fire of big guns, on to the inner works.

A British View

Whether the forts of Antwerp (and, of course, Liege and Namur) were obsolete and not adequately gunned to meet this new and devastating attack, or whether there are other military reasons to explain the rapid fall of the town, will form a topic for expert quarrelling for many years to come. It is, however, interesting to note the views expressed by no less an expert than Lord Sydenham in an interview with the Manchester Guardian on the matter of the Belgian forts and their abilities to resist modern guns. Lord Sydenham ranks himself in opposition to the school of modern experts who pin their faith to the steel and concrete forts, and when Brialmont, whose teaching forms the gospel of Lord Sydenham's opponents, was building these very works that were to be impregnable, and which have so quickly succumbed, he had sufficient faith in his theories to break a lance with the man who was considered to be the greatest of modern military engineers, that is with Brialmont himself.

Lord Sydenham's View

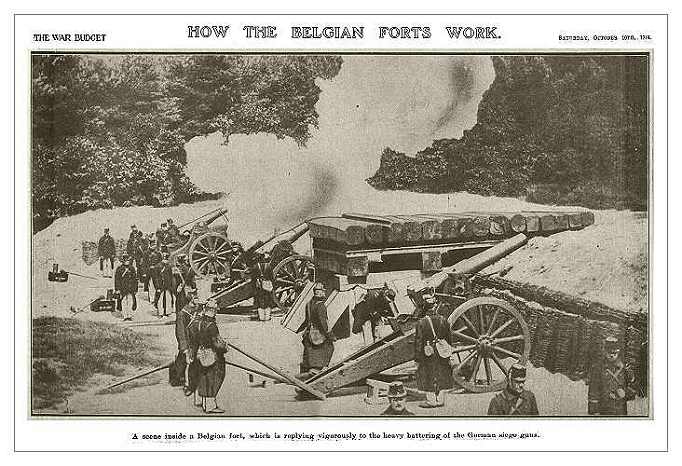

"In my controversy with General Brialmont," said Lord Sydenham, "I maintained that it was no use placing guns in forts, and I urged this view nearly twenty-five years ago. What is necessary is to provide shelters for the men, to which they can quickly retire when they are being shelled, and strongly entrenched lines with effective obstacles for defence when the enemy's infantry comes close. I got that idea from the Siege of Plevna, on which I wrote a book in 1879. That place was defended mainly by rifle lines, because the forts were small and inconspicuous, so that the Russian fire did not damage them. You must have your artillery defence quite independent of the forts, placing the guns and howitzers in the intervals, well concealed, and so organised that they can be moved about from place to place. This is the principle which I advocated in my book published in 1890. This principle was strongly confirmed by what happened at Port Arthur, where the permanent forts acquitted themselves badly, as usual. It was in attacking the improvised defences on 203-metre Hill that al] the heaviest Japanese losses were incurred. These entrenchments were the backbone of the defence.

Artillery Firing from a Belgian Fort

The Faults of the Belgian Forts

"I went to Belgium in 1890 at the request of King Leopold to report on the forts that were then being constructed. I strongly condemned the defences of Liege and Namur.

"The forts of the inner line at Antwerp and a few of the outer line, which were then being constructed, struck me as being very bad. The latter were similar to those at Liege, but much larger. What has disappointed me about Antwerp was that I thought that in the long time at their disposal the Belgians could have entrenched themselves in the intervals so carefully, and would have been able to mount so many guns in the intervals, that the loss of a fort need not have compromised the defence. I thought Antwerp, thus strengthened, was capable of holding out for several weeks, and so long as the outer line of defence was held the town could not have been bombarded.

Rough-and-Ready Defences Best

"The experience of this, as of other wars, shows that the best defences are those which have been prepared in a rough-and-ready way to meet the requirements of war. The conventional fortifications of. the great masters almost invariably prove disappointing when tested by experience. The contention that a permanent fort of ordinary type is really a shell trap which cannot hold out in the face of the concentrated fire of modern howitzers is proved by what happened at Antwerp, where neither the armoured gun positions nor the casements were proof against heavy shells. I imagine that the forts at Maubeuge were equafly unable to resist concentrated fire, though a much longer defence was made there.

The Day of the Siege Gun

There you have two vast armies with powerful artillery on both sides who cannot make much way against each other. There are no permanent fortifications at all, and they are fighting in extempore positions created during the course of the war. On the other hand, you see theoretically strong places like Namur and Liege falling without any difficulty at all. In 1870 some of the French fortresses which had not been modernised made a good defence - TouI, for example, lasted 37 days, and Belfort, where improvised works had been added, lasted 103 days - but siege artillery was then much weaker than now."

The Great Guns have Conquered

That is the view of one expert of great eminence; there are others who had different opinions. There are those who maintain that Antwerp fell through treachery; others that spies within the gates were responsible; others that the guns in the Antwerp forts were so inadequate that the garrisons were forced to endure the awful bombardment of artillery placed out of range of their own less powerful guns without being able to strike a blow in return; there are others who argue that, under different military conditions and with adequate support, Antwerp would be still holding out. All these things will come in for much discussion. One fact only is certain, and that is that the great guns have conquered fortifications, and until they are matched against forts of stronger calibre than those of Antwerp, Liege, and Namur, they hold the field.

German artillery firing in the field