From the book

From Mons to Ypres with General French

by Frederic Coleman 1917

First Battle of Ypres 1914

Part 2

CHAPTER XIII

A FRENCH ATTACK

The Germans attacked the line of the Ploegsteert Wood and Le Gheer violently on the morning of Monday, November 2nd. The detonation of the heavy firing came dully through the rain to us. Early in the forenoon the noise of battle lessened, the rain ceased, and the sky brightened.

One who had been talking with Sir John French told of the conversation. "The war surely cannot last much longer," he reported the Field-Marshal to have said. "The butchery is too frightful. The losses in themselves will stop it sooner or later. The enemy cannot stand it long."

So it must have seemed to one who knew what price the enemy had paid to win the few miles of ground he had so far won on our front in Flanders.

The Germans were pressing hard on our line in front of Wulverghem to Hill 73, west of Wytschaete, and north to our positions before St. Eloi. The sound of the guns was incessant.

A cyclist from the 11th Hussars passed our headquarters on the Neuve Eglise-Kemmel road and told me of his regiment, which had been shelled out of its trenches. A First Brigade motor-cyclist supplemented this information. A gap between our strong line of trenches in front of Wulverghem and Hill 75 led across soft ground that presented great difficulties. To prepare it for defence in the sodden state of the low levels was well-nigh impossible. The 11th had been told to hold that part of the line, and had dug themselves in as best they could during the night. The German howitzers had torn the soft fields to bits in the morning, utterly destroying the trenches. Half of the 11th were hit or buried, and the remainder of the regiment was withdrawn to save it from total annihilation.

The enemy tried to follow up the advantage thus gained, grey lines could be seen pushing west from Wytschaete. The French seventy-fives were in action, however, and our own guns were reinforced by batteries from the 2nd Corps. Shells rained on the front towards which the German attack was directed, and it soon fizzled out in front of the wall of fire and smoke that barred the way.

A Belgian staff officer drove past, pausing to tell us of the flooded Yser. From the sea southwards almost to Dixmude, he said, the land was inundated. Germans were drowned in hundreds, their guns were sinking in the all-enveloping mud, and the coast route to Calais was closed to the Huns.

A run to General Conneau's headquarters near Kemmel showed that the road would not long be passable for cars. Great cellars in the pavé road had been dug by the Black Marias, which were falling at frequent intervals all about the district.

The Kaiser had been in Hollebeke the day before, we were told. Incidentally came the news that our airmen had dropped one hundred and ten bombs on that village during the day in honour of His Imperial Majesty's presence. Who could hear such rumours without hope that one of the aerial missiles had found its mark and ended the mad career of the man responsible for the carnage he had come to engineer?

Tuesday morning I spent behind the ruined wall of the estaminet that had been our headquarters on the Wulverghem-Messines road. A house on the eastern edge of Neuve-Eglise had been dynamited out of existence to clear the line of fire for one of our batteries thereabouts. As we passed the pile of debris that marked where it had stood an officer was trying to get a snapshot in the dull light. Later I saw the result of his efforts in the form of a picture in a London paper. Under it was the inscription, "The work of a German shell." A large amount was advertised to have been paid for the photograph.

Shells came so close to the ruined inn during my sojourn behind it that I took to the ditch, snuggling down behind the dead body of a red cow that had been thrown from the field to the ditch the evening before.

The 1st Cavalry Division held the Wulverghem line, the 3rd Corps on the right and Conneau's Cavalry on the left. Sir John French had sent a commendatory despatch to de Lisle's Command, asking us to "hold on." It might be a matter of days or only hours before support came; we were to keep the position at all costs until its arrival. The 2nd Cavalry Division was in billets, to be called up6n by the 1st Division if its assistance became necessary.

While the day was young the enemy forced back the French line on our left. De Lisle ran to the headquarters of a French general, whose troops were bearing the brunt of the attack, and sent the 1st Cavalry Brigade up on his flank. French wounded littered the highway. The seventy-fives were firing with wonderful rapidity from a dozen positions near by. Kemmel came in for a rain of howitzer shells that made the vicinity a most unhealthy spot.

Foch attacked on Conneau's left, hoping to drive the enemy from Wytschaete, and then press on to retake Messines. Excitement reigned. A wave of optimism engulfed everyone. Our 2nd Cavalry Brigade could see the French attack from their trenches. De Lisle moved up to the ill-fated estaminet. All eyes were on the French. When they could be seen approaching Messines de Lisle was to let the 2nd Brigade loose. The 1st Cavalry Brigade would also attack Messines from the south-west and the 3rd Army troops close in from the west.

The ceaseless roar of guns intensified in fury. Stray shells began dropping in threes and fours close to our headquarters. Pieces from one of them spattered the walls and rattled on the tiles of the roof.

At General Mullins's headquarters back of Wulverghem shells were falling in even closer proximity. One splinter came through a window of the cottage occupied by Mullins and his staff and found the slim form of Jeff Homby, but fortunately damaged him so slightly as to wound his feelings more than his attenuated anatomy. The irrepressible spirits of the 2nd Brigade staff bubbled forth in unquenchable hilarity at this incident, and messages of mock condolence were showered on Homby, as though the very war itself were one huge joke.

In the midst of the fun the laughter subsided abruptly on the arrival of Lieutenant Chance of the 4th Dragoon Guards. The boy was covered from head to foot with dirt, as though he had rolled in a mud bath. His hand had been painfully smashed by a shrapnel bullet. He came in to report that he had been compelled to pull his squadron back from the line to a position not far behind it.

Chance was one of the many junior officers who were in senior positions in those days of heavy casualties. His squadron had been on the right of our line, adjoining Conneau's Frenchmen on his left. His task was the holding of the soft sandy ground that had been so shell-swept the day before. Digging a deep trench line, his lot "sat tight" under a bombardment that had been terrific. A senior officer on the left of that position told me later in the day that for thirty-five minutes the bursting shells over Chance's squadron formed a curtain of fire that hid from sight the windmill just beyond.

Eight, sixteen, twenty-four, and then again eight, sixteen, twenty-four came the Black Marias in line. The ground in front of the trench was thrown up as by a series of mines. Then close behind the trench line, eight, sixteen, twenty-four, until the soft ground caved in in all directions and no trenches were left. Men were buried alive in squads.

Digging out those who had not been buried so deeply as to be hopelessly immured, Chance led his men back, through a hell of shrapnel fire, to the protection of a road- bank a little to the rear. Not a rifle was unchoked, and some time had to be spent in cleaning them. Wiping the sand and dirt from their mouths and eyes, they cheerfully followed the young officer up to the ruins of their trenches and began digging themselves in again.

Once more the German howitzers were turned on them, and once more they were buried in their obliterated trenches. Again Chance took the remnants of his squadron back to the road-bank. Realising the futility of further effort to hold the line where the trenches had been, he adopted the new position and improved it as best he could for defence. The wound in his hand, received during the early part of the morning, became so painful he came back to get it dressed, but before seeking the doctor he called on Mullins to acquaint the General of what had taken place, and to apologise for having to give up the part of the line that had been assigned to him.

Chance was only one of many youngsters who showed such mettle. Truly an army containing a multitude of youths of that mould may be well termed invincible. The lads among the officers were given full opportunity in the Messines fighting to show their worth. The few days on that front cost the 1st Cavalry Division seventeen officers killed and sixty wounded. The total Divisional casualties were not far from seven hundred.

It was evening before we gave up all hope of the success of the French "push," but it could not get on. Guns, guns, guns, all day. Aeroplanes sailed over friends and foes. The latter dropped streamers in the sunshine, and at dusk fire-balls, over us. Shells, shells, shells, till one wondered if the supply was inexhaustible. One of our airmen reported that our guns hit a German battery twice sure, and possibly three times. Our gunners said the Huns did our batteries no harm, in spite of the incessant shelling.

A G.H.Q. summary recorded that "the absence of men in the active list from amongst the prisoners captured during the last month is remarkable, and seems to point to the exhaustion of that class. Between the 14th and 20th of October 7,683 German prisoners have been interned in France, excluding wounded. News from Russia continues to be good."

That was the news from the outside world to us. Our news in return was no more or less than that we had "held on," and darkness had come on another day of continual struggle.

In the night the dismounted French cavalry filed past us in two long lines. On one side of the lane little fellows trotted along in red trousers, light blue tunics, and high-peaked blue caps to match, armed with short carbines and big sabres strapped to their backs, with a great blanket roll atop. On the other side marched the orthodox cuirassiers, tall forms in dark blue coats and capes, their helmets cased in cloth covers.

With every hour the enemy was to find our thin line growing stronger and his last chance of breaking through on that front fading away. The day cost the 4th Dragoon Guards two officers killed and two wounded and over thirty casualties among the men. Only seven officers in the 4th Dragoon Guards were left. The 9th Lancers, too, lost a couple of officers and several men from the everlasting shell-fire.

Conneau's attack brought his line 300 yards nearer the enemy.

Late at night the 2nd Cavalry Division took over our trenches, and we stood in support of them, the men gaining a momentary respite from five days of incessant battle, during which hardly a man, from general officers to troopers, had his boots off.

A sad incident marked the next day. Lieutenant George Marshall, of the I ith Hussars, an aide on General Allenby's staff, and a universal favourite, went to Ypres with a fellow staff officer, as Cavalry Corps headquarters was resting. General Haig's headquarters were in a hotel in the square at Ypres. A big shell lit just outside, killing Colonel Marker of Haig's staff, and also instantly killing Marshall.

Our headquarters had been moved to a comfortable chateau - just in time, it proved. During the morning the Germans shelled Neuve Eglise, our former home, killing seven and wounding more, immediately in front of the house which had been our domicile for some nights past.

After a second day in support, our troopers again took over the trenches, which meant a night of hard work in the rain and mud. A night attack on the French position on Hill 73 had resulted in some success to the enemy, which made the connecting of our left with the French right a troublous matter in the wet darkness.

The morning of Friday, the 6th, was quiet; at least, judged by the standard of its predecessors. British optimism was at once forthcoming, as always, when given a ghost of a chance. A glimpse of the sun made all forget the mud underfoot. A G.H.Q. officer was authority for the rumour that the Germans were evidently preparing to "get out," and moving their howitzers back with that idea in view. All were willing to accept any cheerful interpretation that might be offered.

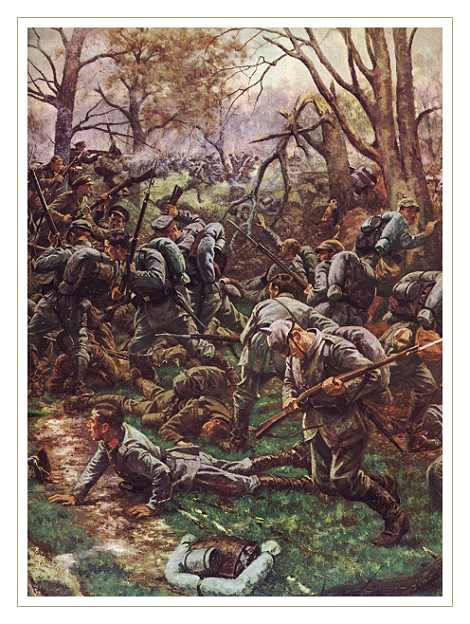

At noon the French gallantly attacked Hill 73 and won it nobly. With a trio of staff officers I tailed along across the fields ankle-deep in mud, watching the advance of the lines in blue. We could see little enough, but quick rushes up slopes not far ahead were now and then visible, and the rattle and roll of small-arm fire so close in front was inspiring. French troops charge over almost impassable ground with unbelievable rapidity.

Our first big 9.2 guns arrived, whereat there was unlimited rejoicing. For days after the arrival of the first one or two to be apportioned to our part of the front, marvellous tales of direct hits far inside the German lines were current.

Visits to the trenches near our old headquarters inn in front of Wulverghem were daily increasing in interest, as that locality was never free from danger. A dozen howitzer shells fell round the ruined estaminet that day as we approached it, but luckily no more followed. The road beside the dead red cow, that I had adopted as shelter in the ditch, was torn by a great shell hole, and paving blocks had been scattered broadcast. Rifle- fire became an added distraction while I was waiting on the hillside, stray bullets cutting leaves from the tall poplars that lined the roadway.

Heavy firing away to the north told of battle towards Ypres. We ran to General Allenby's headquarters on Mont Noir that evening and heard of fierce fighting in front of Klein Zillebeke. The French infantry had been violently attacked and driven out. The 7th Cavalry Brigade had been sent in to make good the line, as the retirement of the French uncovered the right of Lord Cavan's famous Guards Brigade. The 1st and 2nd Life Guards and the Blues had won back the lost ground, but it had cost them dear. Colonel Wilson, of the Blues, and Hugh Dawnay, who had left French's staff to command the 2nd Life Guards, had been killed. Seventeen of the officers of the two regiments had been killed or wounded, and many of their men. To Lawford's 22nd Brigade also was due a good share of the glory of snatching victory from defeat.

Thus swung the tide of battle. One day, in one part of the line, it seemed the rush of onslaught had been stemmed, only to break forth with increased fury in another sector.

What would be the end?

We crawled home to our chateau through a heavy fog. The mud, the deep ruts in the broken pavé the great shell holes in the road, French troops and English along the way, horse and motor transport, an odd battery or two of guns changing position under cover of the night, motor-cars and. motor-cycles, all without lights, made such a run a trial of temper and of skill.

Colonel Seely called and provided some amusement to offset the Strain.

Saturday, the 7th, came, wrapped in cold fog. All night the rifles had spat into the darkness, each side firing at the flashes when they showed dim through the mist.

Once more we poked our way to the ruined estaininet that was our daily port of call. Just before nine o'clock Hardress Lloyd came back from the trenches, where he had gone with de Lisle. He said the General had walked down the line, and we were to make a detour through Wulverghem and meet him on the road to Wytschaete.

In the outer edge of Wulverghem we found a barricade across the street, which had been so solidly constructed that there was no question of pulling it down and getting the car through. Consequently Lloyd suggested that I should put the car under such shelter as I could find, while he walked down the road and explained to the General why we did not come further. I left the car in the lee of a wall while I went on a tour of inspection. I found no one in the village; at least, no one alive. There were four dead soldiers in the tartan of a Scottish contingent down one street, and three dead soldiers who had been laid out, with a sheet put over them. I discovered I was the only live person in the town, which was by no means consoling. A sharp burst of rifle fire started not far on the left, and I returned to the car. Our field-guns had been hard at it since daybreak, and so had those of the enemy, and the small-arm fire had also been heavy at intervals. The French were attacking, and the heavy high explosive German shells were going off with their double rrrumph-r-r-rumph not far away.

I sat on the step of the car, took out my notebook, and scribbled. My notes recorded the events of the next few minutes in detail that tells of effort to forget my nervousness.

9 a. m. - Across the road from me is the convent building which was used as General Allenby's headquarters for some days recently. It is a sight. Every pane of glass in the first story windows is shattered, and many of those in the windows of the ground floor. A great gaping hole in the roof is surrounded by scores of smaller holes in the tiles. The roof as a roof is not of much further use.

"Bang! A shell has fallen in the town. Whizz! Bang! Another one just over me. To go on with my description of General Allenby's house (Bang! another), a big hole has been torn in the wall of the upper story (Bang! one has fallen closer still), and a sister to it appears in the side of the lower story.

"The four shells that last came this way appear to be shrapnel. The French guns are replying, and so are ours. Whizz! There went one that did not burst. Now for the other three to make up the quartette, as the German batteries are apparently firing in fours.

9.30 a. m. Bang! That is number two. Close and just on my left. It exploded. Quite a shower of bits of débris and pieces of shell fell over me. Nasty sound. Bang! Number three. That was a good shell as well, also a bit to the left of me and a little further beyond. A couple of bullets from that one hit the convent. Whizz! and a crash just at my side. That was No.4. Well over and in a fine position. Fortunate that it did not explode, as it could not have been more than eight or ten feet from where I sit, and just across the thin wail which is the best protection that I can find at this point. If it hadn't been a 'dud' they would have more than likely had to cart me out of this rotten town.

"9.08 a.m. Sometimes the German gunners stop after firing a series of eight, and sometimes after a series of twelve. Rarely with this itinerant shelling do they send more than two lots of four, or at the outside three lots of four. There are occasions when they keep it up for a long time. I wonder what will be their policy this morning as regards Wulverghem? One more right where the last one lit would do the business so far as I am concerned.

"9. 11a.m. Beginning to feel better, for it looks as though the eight finished the salvo.

"9.13 a. m. The German shells are searching the vicinity of the town on both sides and in the front and all behind it, but the eight did finish that lot. What luck! They are looking for the French batteries which are firing steadily from quite a number of positions hereabouts. A French artillery officer has come up the road and greeted me with great cordiality. He asked me if I had seen another French officer in the uniform of his battery hereabouts. I have not, and told him so. We passed a joke about the fact. Wulverghem is a nice healthy spot at the moment, and I told him I thought the shell-fire had for the moment ceased. I was con-strained to knock on a piece of wood beside me as I made the remark, which brought a curious glance from the Frenchman. Superstition apparently has no nationality.

9.13 a. m. I dislike being the only occupant of a town that is being shelled. If I could have held the French officer for company I should have done so, but he has returned to his battery, after wishing me good luck.

9.17 a. m. Here, at last, is the General, and I can get out of this place, and back to our headquarters, which I shall not be loth to do."

The General told me, as we returned, that he had been interested in watching the shelling. He, too, had been wondering whether the Germans had commenced a consistent bombardment of the town which would last for some time, or whether they were only dropping a couple of rounds of shrapnel thereabouts. He said, "When I saw they were shelling the town I knew that you would be having an engrossing few minutes, so I remained in the trenches a little while. It was quite as interesting to watch the shelling from that position as it would have been to observe it from Wulverghem, and I did not want to steal any of the enjoyment from you."

The K.O.S.B. and K.O.Y.L.I. went past us during the forenoon on their way to the line. The former regiment suffered heavily during the last hours of the fighting in Messines. A captain told me all but two of his fellow officers were hit and the strength of the Battalion reduced by nearly 130 men.

French infantry moved to the right of our Wulverghem front and planned an attack on Messines for the afternoon. General de Lisle rode up to watch the progress of the French, and said I could come as far as our familiar ruined inn, see what I could, and bring him home when the show was over. At the French General's headquarters we learned that the attack on the slopes of Hill 73, where the line was swaying back and forth each day, was successful. A good length of trench was taken, the Germans leaving scores of their dead in it.

At the smashed estaminet howitzer shells were falling in sufficient numbers to dispel any illusions as to the withdrawal of the enemy's big guns from the Messines area. Odd rifle bullets hit a tree or a broken wall with a nasty smack, and the wicked zipp-zipp of the little fellows came every few seconds. Once a German machine-gun spattered that part of the hill, but the damaged house wall was good cover from any such missiles. The sound of Black Marias shrieking not far above and crashing into the pasture beyond was disconcerting, but they were doing no real damage.

By chance I discovered that a deep trench had been dug in the lee of a haystack that stood at the corner of the ruins of the farm across the road from the inn. There was safety. The field about the stack was littered with dead cows, and monster shell holes were thickly spattered in front of it.

I could see the French and German lines on the sides of Hill 73, not far across a ravine at the foot of the steep slope surmounted by my haystack.

The noise of the bursting German shells and the sharp barking of a number of batteries of seventy-fives behind me was painful. Black Marias fell near in search of the French guns. The noise really hurt me.

When under shell-fire, I have more than once tried to sense the pain of the constant banging as one might define physical suffering. My brain was sometimes numbed, sometimes made acutely sensitive to it. When the howitzer shells came in dozens and scores the sound waves have caused me positive agony of a mental sort. The sensation was indescribable. A tearing at my nerve-centres seemed like to wrench apart some imaginary fabric of feeling and sensibility. It grew unbearable, but generally subsided with a lull in the shelling, leaving me tired, as if having suffered physical pain.

The Oxfordshire Yeomanry were in our front trenches not far away, and one of their officers was on observation duty behind the stack. He saw a company of Germans file down a cross trench a couple of hundred yards in front of the French line on Hill 73, and-at once told the French gunner who was observing in the trenches. Back ran the Frenchman to his battery, to point out the exact spot. In a moment the seventy-fives were sweeping the ridge in front of the French trenches. Back and forth and back again went the devastating shower of shrapnel. "Some observation," remarked the Yeomanry officer with a grin.

As de Lisle had suggested my going into the trenches and "talking to the boys," if I became lonesome, I crept along the roadside ditch that served as an approach trench. "Keep down," came the sharp order as I drew near. I stooped lower. In a tiny dug-out I chatted with a couple of Oxford-shire officers.

One of them, Lieutenant Gill, I had heard mentioned as having handled his men with great coolness on the morning we lost Messines, the first day the Oxfordshires were under fire. Shelled while lying in a beet-field, Gill had quietly moved his men a hundred yards from the path of the howitzer shells, which followed him to his newly-chosen position. Thereupon he as quietly moved the men back whence they had come, losing but few of them. Repeating this maneuver at intervals saved his squadron heavy casualties, and taught them that disregard of Black Marias on soft ground which is so hard to learn, but so comforting when once one had thoroughly absorbed the idea.

The French attack on Messines "made some progress," but was stopped a long way from its objective.

News came at breakfast on Sunday the 8th of the heavy Ypres fighting of the day before. Byng's 3rd Cavalry Division and Lawford's 22nd Brigade were specially commended. Owing to them we regained practically all our lost line at Klein Zillebeke. The French on Haig's right had a terrific struggle and gained a mile.

On our immediate left Conneau reported that the enemy had evacuated some of the Wytschaete trenches, leaving their dead in considerable numbers. The attack on Messines was again to be pressed.

Taking advantage of the cool bright day, General de Lisle ran to the headquarters of the Indian Corps at Hinges. Twenty-three thousand of Willcocks' men were in the line, I was told. General gossip told of Seaforths, whose trenches had been invaded by Germans, only to be bayonetted to a man, and of Ghurkas who hated shell fire, and could not understand why they should sit still under it without retaliation of a personal sort.

The Germans pushed our 3rd Army troops back to the edge of the Ploegsteert Wood during the morning.

The French were confident night would find them in Messines, but were doomed to disappointment.

Waiting outside General Allenby's headquarters at Westoutre the next morning, a 3rd Cavalry Division officer told of a captain in his regiment, killed in front of Ypres, whose body had been found next day robbed of coat, cap, and boots. A listener retailed a story of a visit paid to a French battery by an officer in an English staff uniform, He spoke good French, and showed no less intelligence than interest in the position and the battery's work. Two other British officers came past. Noting the khaki, they called out a query as to the route to a near-by town, and were answered in French. Neither of them had any proficiency in the Latin tongue, and said so feelingly.

"What swank! " said one to the other; "the beggar must want to show off in front of the French chaps."

"Please direct us in English," he concluded to the staff officer. "Sorry to have bothered you."

But not a word of English could they obtain in reply. About to depart in mystification and somewhat ruffled in temper, one became suspicious.

A moment sufficed to prove the pseudo staff officer a sham. He was no other than a German spy in British uniform.

A subaltern of the Warwickshires rode up asking the way to Bailleul. The 2nd Royal Warwicks, the 2nd Queen's (West Surreys), the 1st Royal Welsh Fusiliers, and the 1st South Staffords composed Law-ford's 22nd Brigade, which had loomed large in despatches. We piled question on question. The Brigade was retiring from the line for rest, said the' Warwick lad. Of its original 124 officers only fourteen were left, and its men were reduced to less than half the strength in which they had left England. When the enemy broke through between Cavan and the French the 22nd Brigade and the 3rd Cavalry Division were hurled into the breach. Out of the fourteen officers left in the 22nd eleven were killed or wounded, leaving only three, including Lawford himself, who led one bayonet charge in person. "The General," said the young officer, "plugged on ahead of all of us, waving a big white stick over his head and shouting like a banshee.

There was no stopping him. He fairly walked into the Germans, and we after him on the run. We took the German trench in front of us and held it, but they mowed us down getting up there. How Lawford escaped being hit is more than anyone can tell. I can see him now, his big stick swaying in the air, and he shouting and yelling away like mad, though you couldn't hear a word of what he said above the sinful noise. My Sam, he did yell at us! Wonder what he said?"

The boy rode off down the road in a brown study. It had just struck him he hadn't heard a word his chief had been shouting. He had come through that awful charge alive-one of few to do so. Yet he forgot all that. His own part in the fight never entered his head. "Wonder what he said?" And he rode away thinking. Oh, such men! Could the whole world beat them?

That afternoon I met General Lawford himself in Bailleul, looking fit as a fiddle. After great efforts I persuaded him to dine with us that night at our chateau, on condition that I should convey him there and back, and "not keep him more than an hour," as he was busy.

Someone from St. Omer told me the " Terriers were coming out in increasing numbers. The 10th Liverpool, the Black Watch, and Leicestershire Yeomanry were across the Channel, soon to be followed by other Territorial Battalions.

General de Lisle had watched with increasing interest the splendid observation of the French gunners and the terrible execution of their seventy-fives. Taking Major Wilfred Jelf, our Divisional gunner, he ran to the ruined estaminet in front of Wulverghem to spend an hour or so watching French gun practice.

As I pulled up at the familiar spot I saw ample evidence that the Germans had been paying marked attention to our former headquarters since my last visit. Six or eight new and good-sized shell holes showed black in the soft earth of a nearby field.

The rickety old chair I had rescued from the débris a few days before and placed in the lee of the wall was smashed and tossed aside. A stretcher which had stood against the wall for some days was broken in pieces. The pavé road was badly battered, the grey stones of the surface being spattered with holes of varying sizes and ground to white powder. Odd-looking little holes those, and sinister in appearance, telling of flying splinters of stone, not less deadly than pieces of shell.

As we crossed the road and entered what had once been the gateway of a farm, one of the buildings a mass of ruins well burned out, was blazing fitfully.

Two partially burned rifles were mute evidence that some soldiers had been about when the building had been struck.

Of the two buildings that still bore some semblance of their original form, one had been as completely demolished by high explosive shell as had its fellow consumed by the flames. It had not caught fire, but shell after shell had passed through it till the mere skeleton of a building was left.

A signal corps man in a trench behind a haystack at the corner of the farm reported that his wire had been cut half a dozen times by shells that afternoon. While cut off from all possibility of communicating with his fellows, he busied himself by counting the German shells. During the first thirty minutes he had counted fifty that had fallen within a short radius.

The German gunners were evidently of the opinion that the French batteries were closer to the estaminet.

In order to reach the French observation officer we walked down the road in the direction of the front trench. The enemy trenches at this point were about four hundred yards from our line. It was growing dusk. We covered a quarter of the distance, when a shrapnel, followed closely by three more, burst almost over our heads. Had we been in the field on the other side of the hedge beside which we were walking we should have been in the direct path of the shrapnel bullets. All three of us stepped down into the ditch that ran by the roadway. I ducked as low as possible as we quickened our pace to the trench in front of us. Four more shells, closer it seemed than the first four, burst over us just as we reached the shelter of the trenches. The General and Jeff went into a tiny dug-out with two officers of the 2nd Life Guards, and I crawled on my hands and knees into the mouth of the main trench. This trench was fairly deep, and at the bottom the men had hollowed out a snug shelter underneath the front wall. The men, lying head to feet at the bottom of the trench, well under the cave roof, were quite secure.

The French batteries behind us began a fast and furious reply. The enemy's fire quickened in turn until shells were bursting with nerve-racking regularity over the roadway immediately behind us.

I could find no room in the bottom, so lay in the approach part of the trench. How I did wish for a foot or two more depth to the end of the trench that was left to me!

The French batteries continued to fire steadily. They were shelling a farm in the near distance in which the enemy had placed a group of machine guns. As dusk approached apace, the Germans were afforded an increasingly better target by the flash of the seventy-fives close behind us. After fifteen or twenty minutes of nerve exercise the General decided that he must return to the car. So many successive quantities of shrapnel were bursting over the road that to return by the way we had come seemed suicidal. The Germans now and again turned their guns on to the ruined inn and the farm. I told Jeff I was sure they knew we had to go back there for the car. But jokes fell a bit flat in that atmosphere.

Finally the General tried a detour. Walking down the road a few yards, we turned across it, when we reached our trench line on the further side. I glanced down in the trenches as we went behind them. The men were lying tight and close at the bottom. A French observer who was in the hedge by our side warned us to keep low on account of the French shells that were screaming over our heads.

As we turned back towards the car the French guns seemed to throw more vigour into their firing. The swift rush of the shells and the sharp bark from the muzzles of the seventy-fives so little distant made one think uncomfortably of prematures. Once in a while shells will burst before their time and scatter from the very mouth of the field- piece death and disaster to him who chances to be in the near foreground.

A bough from a low tree under which I was standing was cut by one of the French shells. I ducked and involuntarily jumped for a near-by trench. I was at once called back by the General, who was off across the open space before I could catch up. As I stepped through the hedge a rain of German shrapnel, from twelve to sixteen coming at once, burst over the part of the field just ahead of de Lisle.

We could not veer further towards the French batteries, as to cross their line of fire at any closer proximity would have been madness. It was equally unwise to stay where we were. To return to the trench which we had been occupying might very well have landed us in difficulties, and, at all events, would find us no nearer our objective - the car and "home."

The General walked steadily across the field, unmindful of the shrapnel. I was never more sure of being hit. I hardly know whether I was paying more attention to the French guns roaring away and their shells whizzing over our heads or to the enemy's shrapnel bursting in front of us, on our right, over us, seemingly everywhere about us. I kept my eyes strained in the dusk for shell holes which were deep enough to offer some shelter. Had I been alone I would have run, I think, rabbit-wise from burrow to burrow rather than walk so steadily and with such maddening slowness across that awful beet-field.

In the centre of the field we suddenly stumbled across an empty trench. Much to my delight the General suggested that we should retire into it for a moment. As I lay prone in the bottom of it the shells continued to come over, bursting not far above. We were quite secure unless a shell actually came into the trench and burst, in which circumstance we would have been, as Jeff said, "finished up properly and consequently beyond all worry." Turning their attention from the field for a moment, the Germans began to burst shrapnel over the ruined estaminet. Time and again the Major, after a particularly violent burst of shell, remarked, "That lot finished the car thoroughly, I think." De Lisle was of like opinion. I said that I hoped that the Germans would keep on firing at the car. It was much better than to burst big and little ones all around us. "But," said the General, "I certainly don't want to walk - “

"I do," said I. "I would be quite willing to walk home and walk back again to get out of this.”

Once or twice we started to leave the trench, but each time the French batteries seemed to quicken their fire and the enemy shelled back violently in turn. When it was almost dark we cut across to me of trees, then up towards the road, leaving the tree line for the temporary shelter of a low hay-stack in an open field not far from the motor. I sallied forth to the car, losing no time. I started the engine, jumped quickly into the seat, and dashed away from the estaminet. Pausing a moment to pick up the General and Jeff by the haystack, I sped down the hill towards safety.

Inspection of the car on the following morning showed a couple of jagged holes in the sides of the body. A large piece of shell had gone through an empty petrol tin, and ruined a rug in the tonneau. So but little damage was done after all, save to my nerves.

We were gaining the belief that German high-explosive shrapnel defeated its own object. The propulsive power necessary to scatter the bullets was often counteracted by too powerful a bursting charge.

Lawford dined with us as promised, and told us something of the hard times that had fallen to the lot of the 7th Division, which had but forty-four of its officers left and only 2,336 of its 12,000 men.

The 1st Cavalry Division was once more in the trenches on the morning of Tuesday the 10th. General de Lisle started early for the front. We passed Neuve Eglise, running to the Brewery Inn on the Kemmel road. Marks of shell-fire showed this spot an enemy target, so it was voted unhealthy for headquarters. A point near Wulverghem was reconnoitred, but dead horses were near-by in such numbers and state that we returned to Neuve Eglise and settled in our old home. German shells came daily to Neuve Eglise, a fact that caused some thought to more than one member of the staff.

The location of headquarters for the day having been settled, we visited General Briggs on the Kemmel road, then ran to Wulverghem.

De Lisle rode in front, beside me. Hardress Lloyd was in the tonneau.

At the entrance of the town I glanced at the General questioningly. "Surely," I thought, " he is not going up to that unmentionable ruined inn again. The place is a death-trap."

"Straight on," said de Lisle. Yes, he was going to the estaminet after all.

I set my teeth and "let the car out."

Three seconds later, " Crash! " a shell exploded in our faces. The sound of splintered glass and of the shell striking the car mingled with the deafening blast of the explosion. Bullets whizzed past, striking on all sides. A French soldier close to whom we were passing dropped with a groan.

I felt a sharp blow in the chest and a twinge of pain as I caught my breath.

I reached for the brake. "The General," I thought, "must be hit Lucky I appear to be all right. Now to back round and clear out before number two shell comes.

"Back out of it," came from de Lisle, with sufficient emphasis to show he was alive, right enough.

I tried to put in the reverse, a maddening process on my car at the best of times. Force! Force! the gear would not go in. Any moment number two and numbers three and four, for that matter, might arrive. At last the reverse grated home and I started back.

Turning, I saw de Lisle was sound and unhurt. But Hardress! His face was in his hands, his head bent. Hit! And in the head! I was sure of it. But no, a moment later he assured us he was all right bar bits of glass from the splintered screen that had got into his eyes.

Backing as fast as I could, I narrowly missed a French soldier who had fallen behind us, sorely wounded. Swinging the car round, I headed for Neuve Eglise. No need to stop for the French boy, whose comrades were close at hand. Away we dashed. "Crash !" came another shell as we tore out of the town. I never learned where it struck; all I know was that we were clear of it.

A good-sized piece of shell had hit the heavy plate-glass screen, shattered it to bits, and luckily glanced past the General and struck me in the chest. Had I known of its coming the night before I could hardly have been better prepared. Feeling the cold weather intensely, I had worn an unusual amount of clothing.

A heavy flannel vest, a thick winter khaki shirt, a weird sweater, double-breasted, annexed in Rheims, and my tunic were covered by a double-breasted Irish freize coat. This last had been sent out to me by mistake, as it was dark grey in colour. So unorthodox a garment could not be worn along the lines without a plentiful display of khaki. Consequently I had wrapped round my neck a huge khaki muffler of thickly- knitted wool, tying its ample folds at the chin, and letting its double ends provide me with a wide front of the prevailing shade.

The piece of shell tore its way through the double folds of muffler and played havoc with the great coat. None of the remainder of my voluminous wardrobe suffered, but my breast-bone felt the shock. It was some time before I could believe that it or various ribs attached to it had not been broken. Time proved that a bad bone bruise was the extent of my injuries after all. As the General hadn't a scratch and Lloyd's eyes were none the worse, all ended merrily, save for the car.

A halt at a French headquarters along the road showed that a shrapnel bullet had penetrated the radiator, passing through it, and leaving a clean hole, from which the water was spouting.

"No water of any sort at this farm," said a French staff officer. I hurried on to Neuve Eglise, and from there took the damaged vehicle back to the base for repair.

A halting, limping run found me in St. Omer by afternoon, hors de combat, but hoping soon to be ready to return to duty.

CHAPTER XIV

THE BATTLE IN THE SALIENT

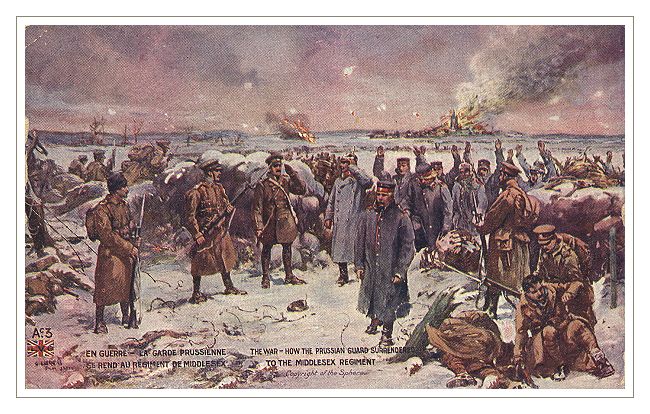

British Postcard : the Surrender of the Prussian Guard

Wednesday, November 11th (1914), marked the onset of the great attack on Ypres by the Prussian Guard.

The Kaiser had spurred his Bavarians, Landwehr and Landsturm to superhuman efforts. No troops could have fought with greater bravery, but they fought in vain. Their failure to hammer a hole in the thin British line left William the War Lord hut one arrow in his quiver-the Guard.

The onslaught of Germany's most seasoned veterans was in keeping with their proud name.

The enemy hurled itself simultaneously against the line held by Haig's depleted 1st Corps, the 32nd and 9th French Corps on his left and the 16th French Corps on his right. Heroic charges were repulsed with enormous loss to the oncoming Battalions, which dashed themselves in solid masses against men to whom fighting had become as natural as drawing breath.

Haig's troops met the brunt of the fight along the Menin road, in the vicinity of Gheluvelt. One Division of the German Guard Corps, a portion of the 11th German Corps and a portion of the 27th Reserve Corps surged forward indomitably, and drove our 1st Division from its first line of trenches, only to have the most of the ground gained torn from them by such counter attacks as warfare had never seen before.

The story was told simply and effectively by Haig's general order of the 12th. This read as follows: "The Commander-in-Chief has asked me to convey to the troops under my command his congratulations and thanks for their splendid resistance to the German attack yesterday. This attack was delivered by some fifteen fresh Battalions of the German Guard Corps, which had been specially brought up to carry out the task in which so many other Corps had failed, viz: to crush the British and force a way through to Ypres.

"Since their arrival in this neighbourhood the 1st Corps, assisted by the 3rd Cavalry Division, 7th Division, and troops from the 2nd Corps, have met and defeated the 23rd, 26th and 27th German Reserve Corps, the 16th Active Corps, and finally a strong force from the Guards Corps. It is doubtful whether the annals of the British Army contain any finer record than this."

De Lisle's 1st Cavalry Division came out of the line in front of Messines on the evening of the 11th for a well-earned seventy-two hours' rest. For ten days little or no opportunity had been given to take stock of heavy casualties and refit.

The men left the trenches on Wednesday afternoon,. and at dinner on Wednesday night orders came to Headquarters that the Division must move to Ypres at once in support of Haig's men, to whom, after three weeks of constant battle, had fallen the task of repulsing the fiercest attack of the whole war.

The 1st Cavalry Brigade was on the road to the north by 11 p. m. and the 2nd Cavalry Brigade an hour later, all thought of the seventy-two hours' rest forgotten, eager to press on to the succour of their gallant comrades, with such strength as in them lay. That strength was not to be gauged by their attenuated numbers, for the troopers, who had held on to Messines till the ridge was lost and their withdrawal ordered in consequence, were equal to a force of the enemy outnumbering them by six to one.

The 12th they spent in the salient in reserve, and on the 13th, Friday, they took their places in the line and showed their temper to the Prussian guards-men.

My shell-smashed radiator temporarily repaired, and my chest better for a few days' doctoring, I rejoined the Division on Friday evening, as it was going into action.

The days required for the repair I had spent in St. Omer, at G.H.Q. Rain fell unceasingly. The work on the car was carried on in the open, regard-less of the storm, the mechanics standing ankle deep in a quagmire of ooze and mud. Efficient repair seemed well-nigh impossible under such circumstances, though the men worked like Trojans. Oftentimes they toiled far into the night, for no matter how diligently they strove, broken down cars surrounded them in droves, their impatient drivers clamouring ceaselessly. Poor Scott, the A.S.C. Captain in charge of the repair park, was vainly trying to do the work of ten men.

Retiring to the cosy Café Vincent I delivered myself to the tender ministrations of a pretty auburn-haired waitress, who had become the pet of junior officers at General Headquarters. The soup was excellent, and then came sardines. Heavens, was I never to escape them! Sardines, alternated with their more lowly blood-brethren maquereaux, had dogged our footsteps for months. Even in the most opulent hostelry in St. Omer they followed me relentlessly.

After a careful search of the town I found a yardstick marked with inches, the property of a local draper. From it I made a tape measure. With a friend's assistance careful figures were compiled and despatched to my London tailor. A winter uniform was a necessity. Aghast at such a falling off in my ample proportions, the man of scissors and thread in London town obeyed my behests. A month later the new clothes arrived. To my horror they were so small I could not get into them. Research showed the St. Omer yardstick to have been a delusion and a snare. Its inches were marked for profit, not for accuracy.

An evening in the Hotel du Commerce at St. Omer was great fun. Harry Dalmeny, Shea, Baker-Carr, Hindlip, and kindred spirits gathered at dinner. Marlborough was sometimes present. Jack Seely discoursed at length on subjects concerning all and sundry, Dalmeny ever joking him unmercifully. A stranger whose ears caught the conversation would have been shocked to hear Seely told that all ills of the Army were due to rottenness of the administration of his office on the part of that Minister for War who held the portfolio the year preceding the outbreak of hostilities. But Seely was imperturbable. Nothing ruffled him. Not even Dalmeny's oft-told tale of Seely-" I am Colonel Seely. I have been directed by the Commander-in-Chief to receive and impart information." This, according to Dalmeny, was the invariable formula hurled at staff officers dashing past in the heat of battle or in the stress of frantic hurry at some critical moment of the retreat. It was all good fun. Every man present knew Seely as a very gallant officer. F. E. Smith's languid sarcasm glanced off the hardened front of this gay gathering like feathered shafts from a coat of mail. Freddie Guest and Guy Brooke were neither of them strangers to the party.

An unusually severe downpour made my departure from St. Omer for Ypres a wet business on Friday, the 13th. I missed the comfort of a hood. A new hood for my car had been ordered from England, but was to lie, mislaid, at Woolwich Arsenal for many a long week.

Past Cassel on its hill-top, the road lined with camions awaiting French reinforcements, soon to disentrain from the south, I sped to Steenvoorde and Poperinghe. A veritable nightmare, that run. Of all the maddening road obstructions the Algerian horse and cart column easily took first prize.

At Poperinghe application to Headquarters of Echelon B of Haig's Corps produced the information that the 1st Cavalry Division was "somewhere on the Menin road, east of Ypres." I was recommended to "proceed through Ypres and push on east a few miles, then enquire again." Cheerful!

A newly-fledged fleet of Red Cross ambulances worked its way autocratically on toward my goal, and I fell into its perturbed wake. At last, a block - impassable. West of Ypres, at the railway-crossing, traffic was banked up like a log-jam. French horse-transport, side by side with ubiquitous British lorry drivers in considerable force, tried to forge eastward over, around, or between a column of French cavalry and a Brigade of British field-guns, which were persistently disputing the right of way to the west. French officers shouted orders to English gunners, who swore softly, while a British officer ploughed through the sticky mud and drenching rain, urging reason on French cuirassiers, who politely wondered what in the world he wanted. A tired jehu behind the wheel of a lorry laughed loudly as a flare showed a mud-plastered sergeant who had lost the road, his footing, and his temper. At the roar of merriment his woe-begone appearance produced, he let loose a searing blast of reproof that was in itself a liberal education in expletive. The driver's laugh subsided to a chuckle, then died in wonder at the storm it had unwittingly raised.

Entranced, I watched the scene till I caught sight of Major Macalpine-Leny, of the 1st Cavalry Division Staff. Hailing him, I learned de Lisle's whereabouts, and pushed on, when the block cleared, to Divisional Headquarters on the outskirts of Ypres.

From Ypres the flash of guns showed through the pitch dark of the rainy night in front, to left and to right. German shells were falling in most unexpected quarters. No rule or reason seemed connected with their arrival, save to make night hideous with their din and chance a hit at bodies of troops or transport moving in the night.

Howitzer shells exploding near at hand, momentarily flashing from the blackness ahead, produce a picturesque effect for all their terrifying detonations.

The 1st Corps units our Division relieved were sadly cut to bits. One Battalion consisted of but two officers and sixty men. Another had only one officer left, and numbered less than two score all told. We found a Brigade headquarters with a major in command, whose brigade-major was a subaltern.

On all sides stories could be heard of terrible slaughter inflicted on the enemy. The Guard had come as if on parade, men said. Whole regiments had withered away under a stream of fire, and others relentlessly advanced over their dead bodies as if unmindful of their own certain fate. A gunner told me one Battalion of the Prussians had broken through our line and marched straight towards our guns. Coming within one hundred yards of his battery, they had literally been blown back from the very cannon's mouth, leaving 500 of their dead in ghastly heaps to mark the limit of their bold advance.

I saw half a hundred prisoners, huddled in the rain, examined by lantern-light. Fine, big men, broad-shouldered and tall. They looked defiance on their captors, as if to remind the hated English they were German Guardsmen still, though their teeth were drawn and their comrades littered the slopes they had thought to win.

Haig's heroes were generous in their tales of German bravery. Death held no terrors for the Guard, they said. I was often reminded of this as the days wore on. The German line would surge up to our trenches only to be swept away, the remnants staggering back from the withering fire. Recovering from the shock of the recoil, small detachments, twos and threes, dozens, or perhaps a score, would come trudging back where death was being dealt out with lavish hand. Some marched boldly, more came doggedly. Many were seen advancing with an arm across their eyes. These futile maneuvers, always ending in the total annihilation of such a group, were inexplicable until a captured German officer gave the key. Men of some Battalions, he said, ever remembered that their regiments had never known and never could know retreat. Death, yes, but not retirement. There was no place at the rear for them, so they went on to join their fellow comrades in a glorious death.

It was better so, from our standpoint. Every dead German meant one less with whom to deal. It may have been magnificent, though none but Prussians would have called it war.

Haig's troops held men who never thought they would have an active role in the Ypres fighting. Cooks, orderlies, officers' servants, and transport men were called into the line to reinforce the thin Battalions.

I saw soldiers who had spent eighteen continuous days and nights in the actual firing line without respite or reprieve. No billets for them, save the water and mud in the bottom of the trenches, to which they were hanging by tooth and nail. Bearded, unwashed, sometimes plagued with vermin, the few who remained in that front line were a terrible crew.

One of their officers, unshaven, unkempt and unbelievably dirty, told me the remnants of his command might be divided into three classes. One or two had succumbed to the frightful physical strain and were broken past all probable recovery. The rest were sullen or fierce, according to temperament, equally to be dreaded as fighting units. Whether they killed with a lustful joy, half-wildly, or with the deadly matter-of-fact calm of desperate determination, killing had become the one paramount business of the hour, and never ceased for long.

Such was the handful of bull-dog breed against which five to one and even heavier odds of the flower of the greatest Army in the world's history threw itself in vain.

No more glorious achievement rests to the credit of the British Army than that of Haig's sorely tried 1st Corps in the first battle of Ypres.

The fight was by no means over by the 13th. For four days more the struggle was waged with unvarying effort, on the part of the Germans, to break through.

The early morning of Saturday, the 14th, gave me my first sight of the destruction wrought in the ancient Flemish city.' Great cavities in the streets and piles of débris, ever increasing in number, made Ypres barely passable for motor traffic. The Menin road was under constant shell fire, which made me thankful that our Headquarters were on the Zonnebeke road, between Potijze and Verlorenhoek. A room in a modest dwelling served as headquarters. A stream of wounded soldiers, French and British, rolled back towards Ypres. Ambulances passed and repassed, crowded with shattered forms. They had little room for a wounded man able to walk back to a dressing station.

The British line crossed the Menin road about a mile west of Gheluvelt. The irregular front followed the eastern edge of the woods on both sides of the road. The position was well "dug in," and tunnels and underground rooms were scattered here and there.

South of the highway, the opposing lines, a few yards apart, ran through the grounds of the Herenthage Chateau. The Chateau was held by the enemy. Our troops were in possession of the barn. By a fierce attack during the morning the Germans captured this barn, and we heard of the organization of a night attack to regain it.

The salient was alive with French and English batteries. The noise of their firing was ever with us, augmented by a continual shower of enemy shells.

Sharp intermittent bursts of rain hourly spread a thicker covering of slimy mud over the road surfaces. The temperature fell rapidly, and night closed in cold and dreary.

The Northumberland Fusiliers made the attack on the Herenthage Barn. It failed, and the officer who led the assault was killed. A gunner officer volunteered to wheel a field piece to within a couple of hundred yards of the barn and smash it at close range. Five shrapnel were hurled into the stronghold, and a sergeant led the Northumberlands a second time to the attack. This time the charge was successful, and the position was won. The shattered building was a shambles. In addition to its defenders, it had contained a number of wounded when the five shells came crashing through it. Not a soul within its walls was left alive.

An effort to reach Ypres after dusk landed us in a hopeless tangle on the Zonnebeke road. A column of Yeomanry transport, badly handled and very badly driven, was the initial cause of the trouble. The mud in the roadway was ankle to knee deep, and the ditch alongside full of black slime. An R. E. lot from one direction and a long column of French cavalry from the other added to the confusion. One cuirassier became mired-his horse fell, and he disappeared beneath the mud in the ditch. The driver of a mess cart, who constantly reiterated that he was of the " 'Erts," tipped his vehicle over in the midst of the méIée. Hours passed before the tangled skein was unwound. A dozen shells had fallen along that road a few hours before. A dozen more would have caused trouble awful to contemplate had the German gunners known of the jam.

We dined to the accompaniment of bursting Black Marias, though none fell nearer than a couple of hundred yards from us.

Sunday brought a driving sleet. A run down the Menin road and back found it so torn and smashed as to be practically impassable for a car. All day shells traced its length from the trenches back to Ypres. No man who traversed it in those days finished his journey without wondering he had not been hit. Hourly I " strafed " the respective shells that had smashed my hood and screen. The sleet made the work of driving bitterly cold. Still the troops held back the German attacks, and piled up their dead in front of our trench line.

Our own part of the line saw less fighting than other sections that day. An attack by a party of sixty or seventy of the enemy was pushed on as if forced from the rear. One of our staff officers suggested that the German commanders might find it necessary to promulgate some sort of an attack each day, no matter how small its area or how remote its chances of success, "to provide the daily notes for their official diaries."

Numbers of German dead lay close to our trenches. An officer of the 4th D.G.'s was asked why he didn't clear away one corpse that could be reached by a bayonet from the trench. "Oh, sir," the officer replied naively, "he is quite inoffensive."

Lord Cavan was almost a demi-god in the eyes of his devoted men, whose position adjoined ours. What was left of the West Kents, Munsters, Grenadiers, Coldstreams, Irish Guards and London Scottish were in Cavan's force. His personality had figured largely in the stubborn defence of the line. No words could paint his services in too glowing colours.

The German snipers merited and soon gained our full respect. From thirty to one hundred yards from our line in their own trenches, or concealed individually in the wood, woe to the man who unduly exposed himself in front of them. Some of them had notorious records. One at a point in front of Cavan's force had hit nine West Kents, two Grenadiers and a Munster. None of our men could locate him.

Sniping at the Germans was most diverting work. An officer of the 9th Lancers took out a trio of sharpshooters, and in an hour was offered a target at one hundred yards, which enabled his men to "get" four of the enemy.

Monday one of our Brigades was in reserve. The men busied themselves in more or less futile efforts to dry out. The rain never ceased for long.

French troops arrived hourly, and the ferocity of the German attacks seemed to wane somewhat.

That night the 1st Cavalry Brigade was relieved, and sent back to billets in the Flemish farms north of Caestre and Fletre. The next night, Wednesday the i8th, the 2nd Brigade followed to billets in the Mont des Cats-Berthen area.

The ground was white with snow. Incessant rains had turned to freezing blizzards. The Prussian Guard had failed, and the line had held. The first battle of Ypres was finished.

The French troops took over the whole of the Ypres salient. To the British Expeditionary Force was assigned twenty miles of front, to be held by four Infantry Corps. The 1st Cavalry Division was promised four days' rest before a few days in the trenches in front of Kemmel.

The Prussian Guard is halted by the British