- 'Filming the War'

- by LIEUT. GEOFFREY MALINS, O.B.E.

the Romance of the Silver Screen

- FILMING THE WAR - THE BATTLE OF ST. ELOI

- by LIEUT. GEOFFREY MALINS, O.B.E.

For two years the author of this story was one of the Official War Office Kinematographers. During the Autumn of 1914 he was employed by the Gaumont Film Company and was sent by them to take moving pictures, if he could, of actual battles at the front. He was so successful that the next year he received his official appointment and once more crossed to France to make history with his aeroscope camera.

A BOMBARDMENT was to take place. A rather vague statement, and a common enough occurrence; but not so this one.

I had a dim idea - not without foundation, as it turned out - that there was more in this particular bombardment than appeared on the surface. Why this thought crossed my mind I do not know. But there it was, and I also felt that it would somehow turn out seriously for me before I had finished.

I was to go to a certain spot to see a general and obtain permission to choose a good view-point for my machine. My knowledge of the topography of this particular part of the line was none too good.

Reaching the place I met the General, who said, in a jocular way, when I had explained my mission:

“Have you come to me to-day by chance, or have you heard something ?"

This remark: "Had I heard something?" confirmed my opinion that something was going to happen. Without more ado, the General told me the bombardment would take place on the morrow, somewhere about 5.30 a.m.

“In that case," I said, "it will be quite impossible to obtain any photographs. Anyway," I added, "if you will permit me, sir, I will sleep in the front line trenches to-night, and so be ready for anything that may happen. I could choose a good spot for my machine this afternoon."

“Well," he replied, "it's a hot corner," and going to the section maps he told me our front line was only forty-five yards away from the Bosche. "You will, of course, take the risk, but, honestly speaking, I don't expect to see you back again."

This was anything but cheerful, but being used to tight corners I did not mind the risk, so long as I got some good films.

The General then gave me a letter of introduction to another general, who, he said, would give me all the assistance he could. Armed with this document, I started out in company of a staff officer, who was to guide me to the Brigade headquarters. Arriving there (it was the most advanced point to which cars were allowed to go), I obtained two orderlies, gave one my aeroscope, the other the tripod, and, strapping another upon my back, we started off on a two-mile walk over a small hill, and through communication trenches to the section.

At a point which boasted the name of "Cooker Farm," which consisted of a few dug-outs, well below g round level, and about five by six feet high inside by seven feet square, I interviewed two officers, who phoned to the front line, telling them of my arrival. They wished me all good luck on my venture, and gave me an extra relay of men to get me to the front. A considerable amount of shelling was going on overhead, but none, fortunately, came in my immediate neighbourhood. The nearest was about fifty yards away.

From our front line trenches the Bosche lines were only forty-five yards away, therefore dangers were to be anticipated from German snipers. A great many of our men had actually been shot through the loopholes of plates. I immediately reported myself to the officer in charge, who was resting in a dug-out, built in the parapet. He was pleased to see me, and promised me every assistance. I told him I wished to choose a point of vantage from which I could film the attack. Placing my apparatus in the comparative safety of the dug-out, I accompanied him outside. Rifle-fire was continuous; shells from 60-pounders and 4.2's were thundering past overhead, and on either side "Minnies" (German bombs) were falling and exploding with terrific force, smashing our parapets and dugouts as if they had been the thinnest of matchwood.

Fortunately for us these interesting novelties could be seen coming. Men are always on the lookout for "Minnies," and when one had been fired from the Bosche it rises to a height of about five hundred feet, and then with sudden curve ascends. At that point it is almost possible to calculate the exact whereabouts of its fall. Every one watches it; the space is quickly cleared, and it falls and explodes harmlessly. Sometimes the explosion throws the earth up to a height of nearly 150 feet.

While I was thinking. upon the exact point of the parapet upon which I would place the camera, a sudden cry of "Minnie" was heard. Looking up, I saw it was almost overhead, and with a quick rush and a dive I disappeared into a dug-out. I had barely got my head into it before "Minnie" fell and blew the mud in all directions, covering my back plentifully, but fortunately doing no other damage.

Eventually I decided upon the position, and looking through my periscope saw the German trenches stretching away on the right for a distance of half a mile, as the ground dipped into a miniature valley. From this point I could get an excellent film, and if the Germans returned our fire I could revolve the camera and obtain the resulting explosions in our lines.

The farm-house where I spent the night was about nine hundred yards behind the firing track. All that now remained of a once prosperous group of farm buildings were the battered walls, but with the aid of a plentiful supply of sandbags and corrugated iron the cellars were made comparatively comfortable.

By the time I reached there it was quite dark, but by carefully feeling my way with the aid of a stick I stumbled down the five steps into the cellar, and received a warm welcome from Captain ,who introduced me to his brother officers. They all seemed astounded at my mission, never imagining that a moving picture man would come into the front battle line to take pictures.

The place was about ten feet square; the roof was a lean-to, and was supported in the centre by three tree trunks. Four wooden frames, upon which was stretched some wire-netting, served as bedsteads; in a corner stood a bucket-fire, the fumes and smoke going up an improvised chimney of petrol tins. In the centre was a rough table. One corner of it was kept up by a couple of boxes; other boxes served as chairs.

Rough as it was, it was like heaven compared with other places at which I have stayed. By the light of two candles, placed in biscuit tins, we sat round and chatted upon kinematograph and other topics until 11.30 p.m. The Colonel of another regiment then came in to arrange about the positions of the relieving battalions which were coming in on the following day. He also arranged for his sniping expert and men to accompany the patrolling parties, which were going out at midnight in "No Man's Land" to mend mines and spot German loopholes.

from a British news magazine

A message came through by pho1!e from Brigade head-quarters that the time of attack was 5.45 a.m. I could have jumped for joy; if only the sky was clear, there would be enough light for my work. The news was received in quite a matter-of-fact way by the others present, and after sending out carrying parties for extra ammunition for bomb guns, they all turned in to snatch a few hours' sleep, with the exception of the officer on duty.

At twelve o'clock I turned in. Rolling myself in a blanket, and using my trench-coat and boots as a pillow, I lay and listened to the continual crack of rifle fire, and the thud of bullets striking and burying themselves in the sandbags of our shelter. Now 'and then I dozed, and presently I fell asleep. I suddenly awakened with a start. What caused it I know not; every-thing seemed unnaturally quiet; with the exception of an isolated sniper, the greatest war in history might have been thousands of miles away. I lit a cigarette, and was slowly puffing it (time, 4.15 pm.), when a tremendous muffled roar rent the air; the earth seemed to quake. I expected the roof of our shelter to collapse every minute. The shock brought my other companions tumbling out. “Something" was happening.

The rumble had barely subsided, when it seemed as if all the guns in France had opened rapid battery fire at the same moment. Shells poured over our heads towards the German positions in hundreds. The shrieking and earsplitting explosives were terrific, from the sharp bark of the 4.2 to the heavy rumble and rush of the 9-inch "Howitzer" The Germans, surprised in their sleep, seemed absolutely demoralised. They were blazing away in all directions, firing in the most wild and extraordinary manner, anywhere and everywhere. Shells were crashing and smashing their way into the remains of the outbuildings, and they were literally exploding all round.

Captain - instructed his officers to see what had happened to the ammunition party. They disappeared in the hell of shellfire as though it were quite an every-day incident. I opened the door, climbed the steps, and stood outside. The sight which met my eyes was magnificent in its grandeur. The heavens were split by shafts of lurid fire. Masses of metal shot in all directions, leaving a trail of sparks behind them; bits of shell shrieked past my head and buried themselves in the walls and sandbags. One large missile fell in an open space about forty feet on my left, and exploded with a deafening, ear-splitting crash. At the same moment another exploded directly in front of me: Instinctively I ducked my head. The blinding flash and frightful noise for the moment stunned me, and I could taste the exploding gas surrounding me. I stumbled down the steps into the cellar, and it was some minutes before I could see c[early again. My companions were standing there, calmly awaiting events.

The frightful din continued. It was nothing but high explosives, high explosive shrapnel, ordinary shrapnel, trench bombs, and bullets from German machine-guns. One incessant hail of metal. Who on earth could live in it? What worried me most was that there was not sufficient light to film the scene; but, thank Heaven, it was gradually getting lighter.

It was now 5 a.m. The shelling continued with increasing intensity. I got my apparatus together, and with two men decided to make my way to the position in the front line.

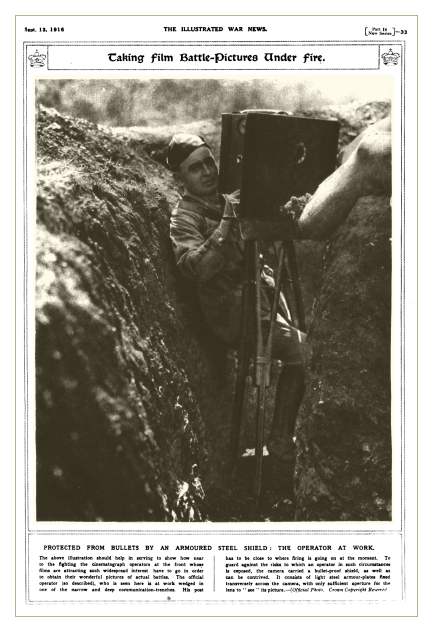

Shouldering my camera I led the way, followed by the men at a distance of twenty yards. Several times on the journey shrapnel balls and splinters buried themselves in the mud close by'. when I reached the firing trench all our men were standing to arms, with grim faces, awaiting their orders. I fixed up the tripod so that the top of it came level with our parapet, and fastened the camera upon it, It topped the parapet of our firing trench (the Germans only forty-five yards away), and to break the alignment I placed sandbags on either side of it.

In this position I stood on my camera case, and started to film the Battle of St. Eloi.

Our shells were dropping in all directions, smashing the German parapets to pulp and blowing their dug- outs sky-high. The explosions looked gorgeous in the ever-increasing light in the sky. Looking through my view-finder, I revolved first on one section then on the other; from a close view of 6-inch shells and “Minnies" bursting to the more distant view of our 9.2. Then looking right down the line, I filmed the clouds of smoke drifting from the heavy (woolly bears) or high shrapnel, then back again. Shells - shells - shells - bursting masses of molten metal, every explosion momentarily shaking the earth.

The Germans suddenly started throwing "Minnies" over, so revolving my camera, I filmed them bursting over our men. The casualties were very slight. For fully an hour I stood there filming this wonderful scene, and throughout all the inferno neither I nor my machine was touched. A fragment of shrapnel touched my tripod, taking a small piece out of the leg. That was all!

Shortly after seven o'clock the attack subsided, and as my film had all been used up, I packed and returned to my shelter.

What a "scoop" this was. It was the first film that had actually been taken of a British attack. What a record. The thing itself had passed. It had gone; yet I had recorded it in my little 7- by 6-inch box, and when this terrible devastating war was over, and men had returned once again to their homes, business men to their offices, ploughmen to their ploughs, they would be able to congregate in a room and view all over again the fearful shells bursting, killing and maiming on that winter's morning of March 27th, 1916.

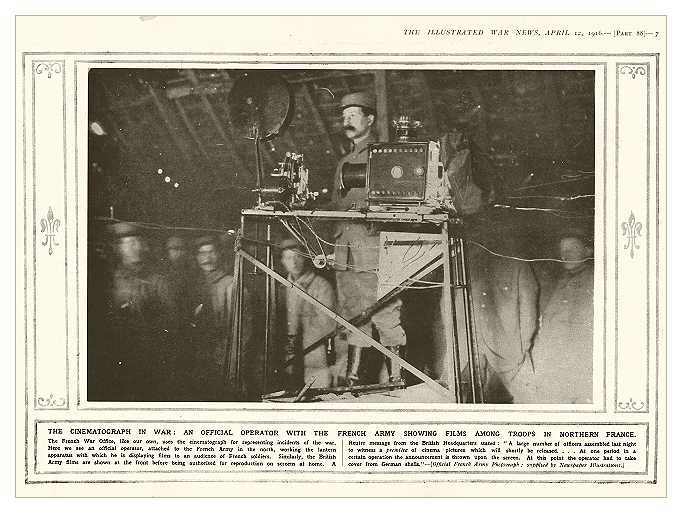

showing a film to French soldiers