- 'Dogs and Wildlife in the Trenches'

- from the book

- 'From All the Fronts'

- by Donald Mackenzie (1917)

Dogs in Warfare

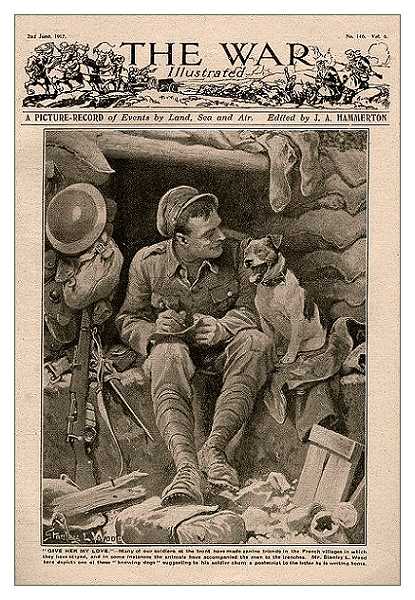

- Always good for a sentimental scene : Man's Best Friend(s) in the trenches

illustrations by Stanley Wood

The dog has long been called "the friend of man", and in this great war it has proved itself to be a friend indeed. Many stories are told of dogs leaving home and tracking their masters to the trenches, and of their wonderful courage under fire. But it is not as a pet alone that the dog has proved itself a "friend", but also as a worker, whether doing red-cross work, sentinel duty, or hauling sledges with supplies over snow - clad hills.

One of the famous French army dogs is "Marquis", which did splendid service carrying dispatches. This faithful animal showed great intelligence, and ran and crept through bullet-swept zones carrying important messages when no human being could venture to do so. More than once Marquis helped whole companies to get out of tight spots by bringing them warnings in time, and it also kept officers in touch with their superiors, when heavy bombardments cut telephone wires, by scampering from point to point with messages. One morning Marquis was sent out on his last journey with a dispatch in his mouth. The Prussians were attacking heavily at the time.

Shell-fire burst above and behind the French trenches, and it was impossible for a soldier to attempt to leave cover. Marquis ran off - going briskly so long as it was under cover. Then he had to cross an open track of country where the bullets pattered down like hailstones. He crept low, and made short rushes from bush to bush, while anxious eyes followed its movements. For a time all went well. Then, when it seemed as if the dog would succeed, it was struck by a bullet and fell on the ground. An officer, who had been watching through his field-glasses, uttered a cry of regret, and began to sorrow for poor Marquis. For a time the dog lay very still. Then he began to come back. Slowly he crept on, suffering pain and very weak from loss of blood. At length, after a great effort, Marquis returned to his master, and, dropping the blood-stained dispatch at his feet, fell over and died.

That evening the French soldiers, with bared heads and heavy hearts, buried the faithful dispatch dog, and set up a little monument to mark his grave.

Another famous dog was named Lutz. It won its reputation near Verdun. One dark night a force of Germans were stealing towards a French position all unknown to the sentinels. Lutz, however, scented them and began to growl.

"Hush! lie down!" a sentinel said in a low voice, but Lutz only grew more restless and excited. The attention of an officer was drawn to the dog's behaviour, and a warning was issued. The French soldiers were roused from sleep and stood ready to deal with any unexpected danger. Ere long they became aware of the near presence of Germans, and a withering fire broke out from the French trenches. The German surprise attack failed completely because of the warning given by Lutz. A large number of this raiding force were killed at point-blank range, and most of the survivors were taken prisoners.

Dogs like Lutz are trained to act as helpers of sentries. They do not all growl and bark when danger is near, however. Some simply "point" like "pointer dogs" used by sportsmen on the moors. When these wise animals scent the enemy, they thrust their noses forward, stiffen out their backs, and signal with their tails, keeping perfectly silent.

One dark night a pointer, named Paul, stood beside a sentry. Suddenly the dog began to sniff and grow restless. Then he pointed stiffly towards a point where he had scented the enemy. An officer was informed that the dog was "pointing". He shrugged his shoulders and said, "The dog can't be trusted." Paul was taken down a trench and led to another sentry post. There he sniffed again and "pointed" in the same direction as formerly.

"Now, Paul," the officer said, "we shall put you to the test."

He ordered rockets to be sent up. Flares of vivid light cut through the darkness, and three Germans on "listening post" duty were seen crouching on the ground less than twenty yards distant. Their duty was to spy on the French position and find out whether any preparations were being made for a night attack. This they could d6 by listening to hear words of command and the movements of soldiers getting ready to creep out in the darkness. If such preparations were being made, it was their duty to creep back and give the alarm.

Having been pointed at by Paul, this particular "listening post" party was rounded up by the French, the three men being brought in as prisoners. The officer patted Paul, and calling him "a treasure", said: "I shall see, good dog, that you are mentioned in dispatches."

The dogs that do ambulance work have saved many lives by going out in the darkness over "No-Man's- Land", after an attack had taken place, finding wounded soldiers, and carrying food and stimulants to them. The intelligent way in which these animals behave is very wonderful. When a red-cross dog finds a stricken soldier, it runs back and leads a party towards him.

On the outbreak of war the French had only a few dogs trained for ambulance work, but these proved to be so useful that their numbers were speedily added to. In less than two years' time there were nearly 3000 dogs at work, and it is estimated that owing to their help about 10,000 lives have been saved.

Among the Vosges mountains large numbers of dogs from Labrador and Alaska have been used to pull sleighs loaded with food or ammunition over trackless wastes, and also to drag small trucks on narrow lines of railway. When snow lies heavily on the ground, and a crust is formed on it by the hard frosts, the dogs can scamper up and down the mountain slopes at great speed. Long teams are yoked to the sledges, and the drivers have exciting enough spins. Sometimes it takes them all their time to keep the animals under control. Running in packs, they often become greatly excited, and scamper at such a rate that there is always the danger of an accident taking place. More than one sledge has been overturned during a wild rush down a steep snowy slope. The dogs follow a leader, who picks out a track by instinct, and occasionally swerves this way and that to avoid a danger spot, such. as a piece of jutting rock, or a deep hollow over which the snow lies thinly. But the bounding animals never swerve if there should happen to be men or mules in front of them.

One day a company of French soldiers were crossing a little valley, when a team of carrier dogs swept down the long sloping hill-side and ran pell-mell towards them. In another minute three or four soldiers found themselves struggling in the snow with foaming and excited dogs tumbling over them. The sledge was overturned, and the driver thrown a dozen yards into a heavy snow-wreath, from which he came out shouting protests, and shaking himself like his dogs to get rid of the sheets of snow that clung about his shoulders and neck. Fortunately no one was seriously hurt. When the sleigh was righted again, and the dogs were got in hand, the driver set his team scampering merrily down the valley.

Much more trouble is caused if the dogs should happen to run into a group of pack mules. The mule is never, as a rule, too good-tempered, and if he is tripped up, he bites and kicks so much that it is dangerous to go near him.

One evening, just as the sun was setting in a blaze of red over the snow-clad hills, a mule, which was thrown over by a scampering dog team, kicked out so fiercely as it sprawled in the snow that it killed three dogs and injured another half-dozen. The sleigh was loaded with ammunition, but by good luck ran down a sloping bank clear of the animal's hoofs. The dogs' traces had to be cut, and three of them escaped, and scampered away out of sight in a few minutes, but they were found next day to have returned to the camp from which they had set out.

As a rule, these sleigh dogs are somewhat wild. They are greatly given to fighting among them-selves, and if one of them should happen to escape from a kennel, they bark and howl at a great rate, and cannot be silenced until the comrade who has won freedom is caught and taken back again. It takes a skilled driver to deal with them when they grow fierce and excited. They are, however, very obedient to, and even quite gentle with, those who feed them readily, and, being most intelligent, answer readily to their names.

But for these dogs, the problem of sending supplies of food and ammunition through the passes of the Vosges during winter would have been a very difficult one. Often when the light railways were buried in snow and rendered quite useless, and teams of pack mules were hardly able to make their way through the wreaths, the northern dogs scampered along, hauling the sleighs and keeping the soldiers well supplied with all they required.

Wildlife in the Trenches

Life in the trenches has brought many men into close touch with Nature, and made them take a great interest in birds and other wild animals whose haunts had been rudely disturbed by the clamour and ravages of war. Flocks of migrating swallows have been seen, at times, in France and Italy, scattering in confusion through the drifting smoke of the big guns, but still they have continued to migrate southward and northward in season as of old without changing their routes in flight. Airmen tell that they sometimes meet in France with swarms of birds soaring high above the clouds. In February, 1917, one flying man saw great flocks of migrating plovers at a height of about 6ooo feet.

Among the lovely Vosges mountains herds of wild pigs have been driven from their lairs by bursting shells. Some have scampered into camps, where they were promptly hunted down to provide a change of diet for the fighting men. One day a wild boar charged down a trench, and wounded two French soldiers before it was laid low by a well-directed bullet.

Sometimes swarms of hares and rabbits have scrambled amidst the network of trenches, seeking refuge from shrapnel and bullets, only to be seized by ready hands and sent to the cook house.

Rats showed no signs of alarm. They clung to the new haunts of men, made themselves at home, and increased in numbers. In trenches and dug-outs they found numerous scraps of food and fared well. But they proved a great nuisance to the soldiers, especially at night, by running over their bodies as they lay asleep in their dug-outs, and nibbling and scraping in every corner in the darkness.

In France singing birds became accustomed to gun-fire, and after a bombardment lasting several hours, could be heard chirping among the branches of trees which concealed the guns. They even made friends with the British gunners, who threw crumbs to them.

One early spring morning, while a little company of blackbirds, thrushes, robins, and sparrows were feeding on scraps that were laid for them on the frosty ground, a big scared -looking cat came creeping stealthily from the ruins of a village near by. The birds rose fluttering and chirping excitedly, but pussy scarcely glanced at them. It had caught a glimpse of an artillery officer peering out of his dug-out, and ran towards him. "Pussy, pussy!" he called softly. The ruffled animal rubbed itself against his leg, and, when it had been stroked gently, began to purr with delight.

It had been somebody's pet, and seemed glad to be among human friends again. Some condensed milk was poured into a pannikin, and the hungry cat licked it up greedily, pausing now and again to look with solemn tender eyes at its new friend, who kept repeating: "Poor old pussy; poor old girl; get on with your breakfast."

The cat finished the milk, licking the pannikin quite dry. Then it lay down to smooth out its coat, evidently feeling quite at home.

On a branch of an apple tree which hung over the entrance to the dug-out a little red-breasted robin watched the cat intently. It seemed to be greatly annoyed at pussy's presence, and kept hopping to right and to left, bunching out its feathers and chirping excitedly, as if telling the other birds what was happening. The officer watched all that was going on as he ate his breakfast at the door of the dug-out. The cat, having finished its toilet, crept between the officer's legs, and began to take a keen interest in the robin, who chirped louder and faster, as if calling out, "Here he comes! he's actually staring at me. 'Mr. Impudence' - that's what I call him." He was joined by two other robins and a sparrow, while a couple of wrens began to scamper up and down the trunk of the tree. All the birds chirped together as if trying to scare the intruder. Pussy bent his legs, fluffed his tail, and showed his teeth as it crept forward, ready to pounce on a bird bold enough to come within reach.

A gun team close at hand was preparing for the morning bombardment, while an officer shouted commands through a megaphone. Then suddenly a gun bellowed with a deafening crash. Pussy sprang into the air with alarm, and bounding back into the dug-out, crept under some clothing and lay still. But the birds never moved. They were accustomed to gun-fire, and knew it didn't hurt. What seemed of more interest to them was the fact that the cat had disappeared. Then the robin who had given the alarm began to think about its rights, and drove the other robins off its branch.

When fighting on the Gallipoli Peninsula our soldiers could not help becoming amateur naturalists. The district was teeming with wild life, and seemed just like a natural zoo. Hyenas prowled through the scrub, and growled and showed their sharp white teeth when soldiers suddenly roused them from their hiding - places. Being cowardly animals, they usually took flight at once. One day a big Highlander was crawling through a clump of bushes to spy on the Turkish lines, when he roused a hyena. It sprang up, with its back against a ridge of rock which jutted out of the soil, and snarled at him like an angry dog. He did not wish to fire, because he knew there were Turkish snipers not far distant, and it seemed to him as if the hyena knew this too. So he could do nothing else but stare at the fierce brute, which looked as if it were about to spring at him.

By and by it quailed before his steady gaze, and began to edge round the rock. Remembering he had read somewhere that wild animals can-not resist the power of the human eye, he followed its movements, staring as fiercely as he could, and not moving a muscle of his face or making any sound. The hyena grew more and more uncomfortable, and began to blink like one who comes out of the darkness into a brightly-lit room. Then it suddenly turned tail and fled. The Turkish snipers caught sight of it a few minutes later, and a shower of bullets spattered all round the soldier; who crept forward to take shelter behind the rock. He lay very still. Some time afterwards, when he moved forward again, he caught a glimpse of the hyena's body lying in the long grass. The snipers had caught it in their fire, thinking, no doubt, they had disposed of a British soldier.

During lulls in the fighting the British and Turkish fighting men held what might be called sporting competitions. In the month of September large numbers of pelican migrated from the shores of the Aegean Sea towards Egypt. They flew over the peninsula in V-shaped flocks, and as soon as a flock appeared in the sky, fire was opened on them with rifles and machine-guns.

One afternoon a flock, which seemed to have come a long distance, began to wheel round in the air as if preparing to settle down on the Salt Lake marsh in Suvla Bay. Suddenly a British machine-gun sent a rippling stream of bullets towards the birds. Not a single pelican was struck, but the whole flock at once became greatly agitated. Then the onlookers noticed that they were under the command of a leader, who made them behave like well-trained soldiers under fire. Shrill screams, like words of command, came through the air, and the birds rose up in extended formation until they were far beyond range and quite safe from attack. Then they continued their flight towards Egypt. As they passed over the Turkish lines, several v9lleys from machine-guns were fired at them; but the clamour only made them fly faster, and ere long they vanished from sight.

After this the British "Tommies" and "Jocks", and the "Johnny Turks", as our soldiers called their enemies, crouched low in their trenches again, waiting for the next flock of pelican. Sometimes, as the birds flew overhead, one was brought down, but it was hardly worth the ammunition wasted upon it. The men on both sides, however, seemed to find the sport exciting, and cheers broke from the trenches when a shot "got home", and a long-necked pelican came tumbling down through the air from what our soldiers called "the flying regiments".

Lots of tortoises crawled about the Gallipoli trenches, and some of our men tried to make pets of those they laid hands on. But a tortoise is never in a hurry to make friends. It is never in a hurry to do anything. A corporal, who kept one tied to a post for a week, coaxed it at length to feed out of his hand, and when he thought it had grown quite tame allowed it to go free. As soon as evening came on it vanished and was never seen again. "You should try and tame a scorpion next," a friend advised the "tortoise tamer", as he called the corporal. " No, thanks!" was the prompt reply. All the soldiers hated the scorpions with their bright-red armour plates, crab-like toes, and uncanny sting-tipped tails, and killed them at sight. Snakes were also dreaded. They came creeping into the dug-outs, and caused many a soldier to jump up with a shout of alarm. One morning, soon after dawn, a big Yorkshire-man woke up to find a snake coiled up on his blanket. He flung the blanket and snake right out of the dug-out, and then, seizing a trench spade, struck at the squirming reptile with such force that he not only cut it in two, but made great rents in the blanket also. It was the first live snake he had ever seen, and he thought the sergeant who told him that it was a non-poisonous one was only making fun of him. "Snakes are snakes all the same," he declared. "Do you expect a man to wait and see if he's going to be stung before he strikes at one?" There are, of course, poisonous as well as non-poisonous snakes on the peninsula.

Then there were the flies, which were even more troublesome than the scorpions or the snakes!

It seemed as if Gallipoli was always suffering from a plague of flies, and our men remembered the Bible story of fly plague in ancient Egypt,. in which Moses repeats to Pharaoh the Divine message: "I will send swarms of flies upon thee, and upon thy servants and upon thy people, and into thy houses: and the houses of the Egyptians shall be full of swarms of flies, and also the ground whereon they are. . . . And the Lord did so.

The land was corrupted by reason of the swarm of flies."

Black clouds of flies came through the air as soon as our men had settled down in their Gallipoli trenches; the insects crawled over the ground, they blackened the dug-outs, they covered men's bodies; they attacked the mules and made them kick and snort and lash themselves with their tufted tails; they crawled over food, and crept into pots and kettles, and were drowned in hundreds when these were filled with water. The flies were a constant nuisance. Men were always brushing them from their faces, out of the corners of their eyes, out of their ears, off their bare arms. And how they buzzed when they were disturbed! Sometimes when the cooks were busy at their work the buzzing of the flies about them was so loud that they had to shout to one another when only a few yards apart. "One morning," a cook has declared, "the humming of myriads of flies reminded me of the noise of a cotton mill in a Manchester street."

When a soldier lay down to sleep during the daytime the flies settled on him in hundreds. Each time he moved and disturbed his tormentors a loud buzzing broke out. If he covered his face with a handkerchief they went crawling over it in such great numbers that it became as heavy as a bit of blanket, and he had to throw it off When, at length, he fell asleep the flies began to take liberties. They ran over his hair, into his ears, and across his face. If his jaw dropped they crept into his mouth. "It was a common thing," a soldier tells, "to see a sleeper who had been on duty during the night sitting bolt upright, half awakened, and beginning to cough and splutter while flies darted out of his mouth. Occasionally a few were swallowed, much to the poor chap's disgust."

At meal-times hundreds of flies "mobbed" every soldier. If one should spread jam on a slice of bread the flies dropped on it at once, and, as a victim once wrote home, "made it look like a slice of currant cake". Another has described how the men took jam with their bread. "First of all," he wrote, "you make a little hole in your jam tin, and keep a thumb on it. You eat the bread dry, and when you want jam you suck it out of the tin, and then press your thumb on the hole again. The flies swarm round your thumb and over your hand, as if trying to make you let go so that they may get a chance of creeping into the tin. You ask me if I have been in a battle yet. I am always in the battle of flies. The flies are harder fighters than Johnny Turk."

Besides the flies there were other insects "too numerous to mention", wrote a Welsh soldier. "There are hundreds of different kinds of grotesque insects, big and small, that crawl about or fly through the air. New arrivals get many shocks. I have seen men who were more afraid of a swarm of insects than a battalion of Turks." He then went on to relate an amusing experience he and others had. "A fresh regiment was having its troubles with the insects one evening when a gale began to blow. It sprang up as suddenly as a bird from the scrub, and came in fierce and rapid gusts that took one's breath away. A great long belt of sun-dried thistles stretched across No-Man's-Land, and the wind cut through the prickly mass like a scythe, shearing off the tops and brittle leaves and severing the stalks, which came whirling in clouds towards our trenches in the evening dusk. A private, who was greatly worried about the strange insects and reptiles he saw prowling about, was cleaning his rifle when a bit of prickly thistle darted past his cheek like a living creature. He sprung back, gasping, 'What is that?' Then another bit scratched his hand as it skimmed down the trench.

A yell broke from his lips. 'I've been stung!' he declared. Hundreds of prickly stalks and leaves then came whirling and darting about the men's ears. Those who thought they were being attacked by swarms of horrible insects of a~ sizes and shapes began to dart into dug-outs; but soon the cries of alarm were changed to shouts of laughter, for word was passed along that the supposed winged furies were simply bits of Gallipoli thistles. As the wind increased in fury the thistle plague grew gradually worse. Heaps of dry prickly stalks and leaves collected in the trenches, and the men were kept busy shovelling them out. Some parts of the trenches were filled to the top. The wind fell before dawn, and when the sun rose you could see piles of thistles all along the line of trenches. It looked as if these prickly heaps would prove troublesome again later on, but in the forenoon another gale sprang up and scattered them across the Salt Lake marsh. As the men watched them they were not surprised that the 'green hands' had been alarmed on the previous evening. The broken thistles skimmed through the air like locusts, and bumped and darted on the ground like giant grasshoppers."

The Gallipoli ants were a source of great interest to the fighting men. They continued diligently working in and about the trenches as if nothing unusual was taking place. "I have watched them for hours on end," a Londoner wrote to his friends, "and wondered at their intelligence. As I write a little fellow is trying to carry a crumb of bread to the nest. He has stuck. The load is too heavy. What will he do now? He is signalling for help, I declare. Here comes a friend to give him a hand! The new arrival has got behind the crumb and is pushing it, while the other hauls again. Now they are making progress. . . . They have halted suddenly. It looks as if they are out of breath. Here comes another helper, I declare! He gets behind the crumb also and they haul and push all together. Up they climb to the door of the ant house. They are going to get the crumb for themselves, sure enough. Well done! They have hauled it inside, and are now, I suppose, packing it into the larder. What wonderful little fellows they are!" I