- A Diary From The Front

- 'Court-Martialed'

- by

- Arthur Sweetser

- Glimpses of the Battle of the Aisne

- My Second Experience as a Prisoner of the French

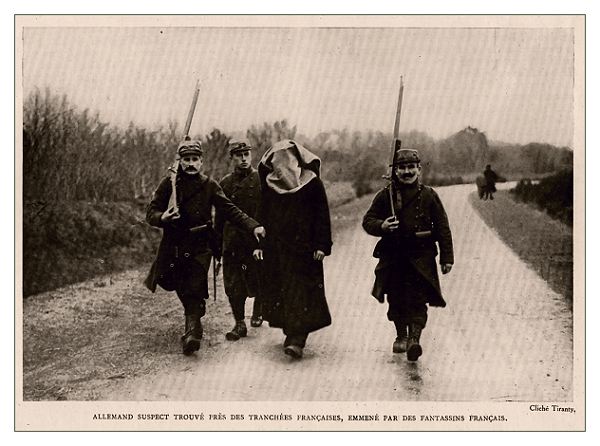

a suspected 'spy' is marched off by French soldiers

Four or five fearful days Paris had hung in suspense, breathlessly awaiting the outcome of the battle of the Marne at its very gates. Official communiqués had been vague and unsatisfactory, and the capital had scanned edition after edition while the German guns thundered just outside.

Then suddenly, unexpectedly, when hope had almost fled, came news of the Germans' withdrawal. Instantly there sprang up a new life. The newspapers became transformed and the whole city reborn. The sadness and anguish which had gripped the gay capital fled in a stream of smiles and joy. The life, the glitter, and the gayety began to pour back. That the German army had been at the very gates of the city and that it might even now be withdrawing only to return was not considered. France had won a glorious victory; the war was all but decided, and it now remained only to quash the last resistance such is the buoyancy of the Parisian.

And for us it meant action. After my long bicycle trip with Von Kluck's army from the Belgian border to Paris, I had become rested and forgotten all about my fervent oaths that I would never again seek to get to the front. The two armies were now deadlocked along the Aisne, where perhaps the biggest battle in the world's history was being waged. Its call could not be denied, and I decided to set out the next day. As a sop to conscience, I tried my best to secure proper papers, but found that I might as well try to break into Heaven. A newspaper man was about as popular as a leper. Consequently, with no credentials at all except an American passport, which had already proved its worthlessness, I set out from Paris on September 14th.

With me was a man named Rader whom I had picked up in Paris and who purported variously to be a newspaperman, aviator, and bomb expert. By dint of tremendous effort we succeeded in getting ourselves, our bicycles, and our knapsacks into the Gare du Nord, where, after another struggle, we loaded the whole entourage on to a train jammed with peasants and sightseers. We hitched our way along as far as Montsoult, where we were unceremoniously dumped out into an inhospitable and deserted country. Beyond that line civilians were not supposed to go, and we knew that we faced practically certain imprisonment and possibly confinement as spies. Nevertheless, we had to see that battle, so we jumped on our bicycles and were off. The first day was uneventful, bringing us to Chantilly for the night.

Early next morning, we set out for Senlis, where I had been prisoner with the Germans at the time the town was burned. The houses and hotels along the Rue de la Republique were now only cold piles of crumbled masonry and half-standing walls.

From Senlis we pushed on through Veberie out into the region of the battle. Now we were once more within the lines, and in danger of arrest.

Along the road we passed a long convoy of nearly one hundred dust-covered Parisian 'buses and great detachments of cavalry already pitching camp for the night, I at once sought out the little inn where I had stayed before and was received very kindly.

The next morning when we awoke a deep, pulsating roar echoed in our ears. Grim, sullen, fearful, the big guns were at their awful work again. It was not unlike the heavy rumble of a violent thunderstorm, yet it was far more awesome. Every moment it seemed as though it must die down and cease, but on and on it went, growling sullenly all about us. The heavy guns of two monstrous armies were snarling at each other till the whole heaven echoed with the ugly reverberation. Thus now for eight days had this sullen undertone been going on just outside this quaint little French city.

Never was noise so magnetic as that of the big guns of the battle of the Aisne. The terrible rumble of this colossal struggle drew us inexorably toward it. We had started for Belgium and had sworn we should not deviate from the road, but when we heard that sullen rumble we were as helpless as straws sucked into a vortex. We could not pass on and beyond this gigantic contest where the great elemental forces of Nature were playing such havoc. We were drawn, irresistibly, irrevocably on.

Of course, we tried to get papers, but found it impossible. The mayor frankly suspected us, and a British officer laconically remarked that he would like to see us when we got back. We told ourselves we were going to Soissons, which was at right angles to the road to Belgium and exactly counter to where our passports read.

An Endless Procession of Wounded

It was a beautiful day as we bicycled out of the city on to a splendid wood road. A rich sunlight streamed through the already reddening trees and gave a welcome warmth to the chill air of the forest. All was quiet with the serenity of Indian summer - all but that ever-continuing roar. Suddenly the significance of it all came upon us. A detachment of French wounded came straggling by. They had done their work; no one longer had use for them; and here they were left to shift for themselves. Through the quiet of the wood road they came like spectres in unending procession. Their march was slow and disordered. Sometimes it was one lone man limping doggedly, on a stick; sometimes two or three, sometimes a whole ragged, bandaged, blood-stained group.

Turcos predominated in that death march. It seemed as if the Germans must have blown up a whole division of them Fierce and bloodthirsty they may be in the heat of battle, but those who passed along that wood road certainly did not look it. Their big, soft eyes, set in clear brown complexions, seemed fairly liquid and melting. Their fezes and baggy trousers fitted oddly in this forest of France.

Suddenly we burst out of the woods. Before us lay a bit of the gigantic battle of the Aisne. To the right was a big meadow land which was one wild, seething mass of men, cavalry, and wagons. Here and there were eddies of movement where one little part sought to extricate itself to go its way. It was the first line of reserves and supplies behind the advance trenches. A little more to the left, the road we were on ran past a thin line of poor peasant homes, past a cross-road leading to the rear, and on through the meadow to the woods on the farther side. Two long lines of wagons and supply trains worked their way along this narrow roadway in opposite directions, one of them turning off to the rear road even as we watched.

Slightly to the left again the land ran down in swampy richness to the River Aisne itself, which here is nothing more than a sluggish stream of less than seventy-five yards' width. Again to the left across the river the land sloped up gently to a long parallel ridge which will probably go down in history as the heights of the Aisne just under its crest could be seen the red of the French soldiers' pantaloons, massed as though preparing to hurl an attack.

A View of a Modern Battle

Crash! A roar from out of the rumble, a puff of white smoke, and a rain of lead on the very men I had been watching! The Germans had found the range exactly, but the distance was too great for me to distinguish what execution they were doing among those serried ranks. Then carne a long siren whistle screeching through the air from the distance. Again a twinkling flash against the blue, again a puff of rich fleecy smoke, and another shell had scattered death and injury on the men helplessly waiting below.

Fascinated, we watched those little twinklings of flame and puffs of white smoke. Whence came they, we wondered, and by what weird skill were they made to burst squarely over their intended prey? Was it the science of man or was it, as we half believed, the cajolery of some demon gloating over the helplessness of his victims?

Again the azure was broken by a little white puff - again we wondered - whence?

Click - click - click - click - click - the murderous machine gun was starting its music. What an engine of destruction! Nothing in the world seems so heinous as the snapping, clacking rattle of the machine gun spitting forth its rain of bullets.

Leaving the forest behind us, we continued on along the road parallel to the Aisne and about a quarter of a mile from the bursting shells. We ran at once into the big convoy that was winding serpent-like along the road for miles. I shall never know how far we came along that road. The dangerous slime made it almost impossible to bicycle, while the jams of wagons forced us out on to a grassy sidewalk which had been equally mashed up by constantly passing horsemen. We had gone hardly a hundred yards through that confusion when we were held up by a mounted officer. Most carefully he read our American passports and then asked me what nationality we were. With a few more words he allowed us to pass on, but again, in another fifty yards, and still a third time perhaps fifty yards farther on, we were forced to go through the same procedure. Each time my heart sank within me and I thought we were caught, but each time we were allowed to go on till it seemed for a moment almost as though we might get across that swampy meadow and into Soissons.

Unexpectedly, however, we were held up by a soldier, who ordered us back with him. He brought us to a plump little officer all decked with braid, sword, and medals, whom I had noticed glaring at us most suspiciously as we passed by. Again I explained how harmless we were and showed our ever-present American passport. With the utmost politeness, he told us that they were splendid documents but that they were not sufficient for sightseeing on the firing line. Equally politely he urged us to return to the headquarters, where there would not be the least difficulty in getting a military pass. By now we had a squad of about thirty soldiers around us, and as we saluted the officer in farewell I imagined I could see an ironical smile on their faces.

Nobody seemed to know where the headquarters were; nevertheless, every time I saw an officer's eye light upon us, I forestalled inquiries on his part by asking him its location. We slipped and slid our way back until a sudden downpour overtook us. Thereupon we took shelter in a little house along the roadside, where a squad of cavalry were lying about, eating a late lunch, or playing cards. They were most courteous and conducted us to an open window where we could look out on the fighting not a quarter mile away across the little river.

What we saw of the battle was most strangely disappointing and depressing. A roar of cannon that was tremendously deep and rich but not at all deafening; little fleecy, almost friendly, puffs of shells; a confusion due principally to mud and an unkind Nature; a little section of the battle bordered on three sides by woods and on the fourth by a hill; half the sweep of the horizon within which to place the enemy's invisible lines; a host of men crouching resignedly in the advance trenches while~ death flared down on them from above-, and behind, another host of men lying about talking and yawning with the foremost thought of getting something to smoke.

Under Arrest

At last the storm passed over and we went on once more over the still more slimy roads until finally we found an officer who was able to direct us. It was another case of the fly going into the spider's web, and I knew for a certainty that we would get in trouble if we ever presented ourselves at the headquarters. Rader was one of those scream-eagle Americans who thought all lie had to do was throw out his chest and wave his American passport; so up we went and got what was coming to us, Briefly I told a staff officer, standing on the roadway with several others, who we were and what we wanted. Most politely, he invited us to go into the yard of a pleasant little country house at our side. We did. The gates closed behind us. I knew I was in jail for the third time on this beastly trip. I was beginning to get disgusted with war correspondence.

Another officer, having found our mission, told us to go into the house. We went in and came out again quicker than we entered. All unknown to us I had turned into the front parlor straight to a sorrowful meeting of the general and staff in charge of that part of the battle of the Aisne, who were decidedly ill-natured because of a serious setback that very day. Something grabbed me by the arm, and when my thinking apparatus got working again I found myself out on the lawn with an excited French officer asking me if I didn't know any better than to go into a staff meeting. Thereupon a gendarme was brought out to take care of us. He led us over near a stable under a tree and immediately loaded his gun with three new bronze cartridges. Pointedly he remarked:

"One for you, one for your friend, and another one in case I miss."

Things were starting now. It had begun to rain again by this time, and we stood there with great big drops dripping down off the tree. For some reason the general happened to come out into the yard, and when he saw us talking together he went off like a bunch of firecrackers at our guard, whom I thought for a minute he was going to have shot. Thereupon Rader and I were not allowed even to talk together.

Court-Martialed

For a solid hour we stood there thus under that dripping tree, afraid almost to look at each other, afraid to smoke, and with no company but our guard and his three new bronze bullets. Then out came an officer to find out all about it. After hearing my impossible story, he whipped his fist up into my face, put his nose about two inches from mine, distended his eyes till it seemed they were going to snap, and shouted:

"You're an Austrian."

It seemed too absurd to deny it, and yet in meek, foolish voice I assured him that I was not an Austrian, but only a poor, harmless American newspaper man,

Then I was dragged inside the house for my court-martial. Three of them got me in a little side room and put me through a third degree.

"Got any arms?" they asked.

"Nothing but a camera," I replied, and their eyes fairly bulged. It was only a little bit of a camera, but it made a tremendous impression, as such things are not popular near a battle line.

"What else have you got?" they asked.

"A German passport to Paris," I replied with all the honesty and guilelessness due to knowledge that they would surely find it on me if I didn't show it to them. Then they rummaged through my knapsack, which yielded them three maps. A camera, a German pass to Paris, and three maps - I wonder if I could have had anything much worse. I doubt it from their expressions. The only ameliorating circumstance was a package of cigarettes, which, judiciously distributed, secured a certain relaxation in the atmosphere.

"Take off your coat," they said.

I took off the dripping garment while they prodded me all over for arms or secret papers. Then for a half hour I stood there in my shirt sleeves shivering in the dampness while they put questions to me. If I was able to control the chattering of my teeth some other part of me would begin to twitch till I was quite sure they thought I was having the palsy born fear. At last the examination was ended and I was sent out into the yard again with a none too comfortable diagnosis of my probable fate. Poor old Rader was still standing out in the rain with his unsociable guard.

Without warning came the order for departure. The general headquarters were retiring for the night and we were going to be taken along with them, Rader, the lucky dog, thus escaping the third degree. It was now pitch dark and raining hard. When we came out upon that slimy road once more, they ranged Rader and me side by side and then, to my horror, brought out a pair of handcuffs. We were tied tight together under lock and chain with only three feet of play. To us, however, fell the honor of leading the march that was to come. It was a motley company indeed-two harmless American journalists, three German soldiers, and five French soldiers who were being sent back for drunkenness. Gendarmes with loaded guns completed the procession.

What a march that was! Handcuffed, in a heavy rain, through an ink-black night, for every three feet we went forward we seemed to slide back two. Rader, slipping and sliding off the side of the road, was in constant danger of tumbling into the ditch beside him. And every time he slipped the chain which bound us dragged me also off toward the side of the road, till my left arm felt as though it were being constantly pulled.

It was hours before we arrived, exhausted and dripping, at our destination, the dingy little City Hall of Pierrefonds, where we were to exist till daybreak.

Sleeping in Manacles

The one large room downstairs had been covered all about with straw. Rader and I shortly lay down on what purported to be our bed for the night. Chilled through with rain, as I was, my mud-soaked feet felt as though they were incased in ice. A thin layer of straw underneath was insufficient to keep out the damp of the floor, and there was absolutely nothing to put over us. I had thought when they sent us to bed that they would unhitch our manacles, but they did not. All night long we lay there, unable to move our arms without pulling the other one into wakefulness. It seemed as though morning would never come. Hopelessly I watched the first gray of another rainy dawn penetrate our jail and dim the flickering lan- terns into uselessness. Finally came time for departure - whither we neither knew nor cared so long as it was away from the place we were in. We were glad to see that the drunken French soldiers were to be left behind, but we were even gladder when our manacles were removed and we each resumed our individual lives. Evidently they were going to allow us to wheel our bicycles, which had suddenly put in an appearance, for one of them conceived the very ingenious idea of taking all the wind out of the tires so that we couldn't jump on and run away. We were not worried particularly, however, as we saw a chance to get exercise and warmth.

Just at this juncture a beastly little captain came fussing around. Oh no, it would never do, to let us go unmanacled. Never! We must be shackled again. I submitted resignedly while the manacle was once more fastened on my left wrist, as now even I was beginning to believe I was a dangerous enemy of France. But the captain's next move was the grand finale. To my horror he brought up one of the German prisoners and fastened him to the other end. With our right hands Rader and I pushed our flat-fired bicycles, while with our left we clung close to our German comrades. I knew all too well what it meant to us all along the march that was to come to be thus manacled to Germans, for there could be but one explanation. There was, however, nothing we could do about it and, as I told Rader, we were taking what was coming to us for having been fools enough to go into the headquarters when told to.

It was dark and lowering when we started, as it had been during all those fearful ten days of battle. Hardly, however, had we appeared in the open atmosphere than it began to open up new torrents. Our wet clothing, which clung heavily to us, became wetter still, and it was a long time before the exercise of walking drove any warmth into our shivering bodies. Mile after mile we struggled on, till I began to wonder if we were going to complete the march to Paris.

French Hatred of the Germans

Everywhere along the road we found evidence of the hostility to the Germans and of the estimate placed on two civilians who are handcuffed to German prisoners. Peasant folk whose houses had been ransacked and emptied of all food and drink by the Prussians when on their march toward victory saw our three companions return as prisoners with a silence that was all too eloquent. Sadly, bitterly, and with hatred showing in their faces, they came to the doors to watch us go by.

Once we stopped and our guard asked if they had some water for us to drink.

"Yes," a peasant woman replied to the guard; "plenty for you, but none for the prisoners."

"Well," said the guard "it's for them I want it."

"We haven't got a drop for them," the woman replied. " Look what they've done to my home. They've stolen pretty nearly everything we had. My husband, who's off fighting somewhere, hasn't any clothes left and they've taken most of mine, too. They can die of thirst before I'll give them anything to drink."

"Yes, I know," said our guard kindly. "But they are men like the rest of us and get thirsty as we do. We're French and must be kind even to our prisoners."

"They were kind to us, weren't they?" the woman replied; "they'll get no water here."

Meanwhile she was eyeing Rader and me in a most hostile way. I could see that we were in a worse category, even, than our German comrades. Our guard argued with her a moment longer and then, drawing himself up, said:

"I command you to bring these prisoners water."

The woman looked at him blankly for a moment and then with a curse in her heart brought us out a bucketful. I couldn't stand it any longer and told her that Rader and I were Americans. She heard me sullenly, but evidently, after looking at the manacles, thought the connection between us and the Germans was too intimate to make us of a very different breed.

Revived somewhat by the rest and the water, we resumed our march. Each little deserted village we came to I thought was our last, only to find we were to go through and out the other side. Eighteen long kilometers [eleven miles] we did that day before finally we came into sight of Villers-Cotterts, the permanent headquarters of the Fifth Army Division.

Spy! Spy!"

Far out in the country we encountered a long convoy, apparently resting for lunch, with hundreds of soldiers standing about and horses eating near by. Not a soldier but flocked to the road to see us pass, till finally we were marching in high dignity through a long double line holding all the way to the town itself. Most of the men were silent, many laughing, and not a few making either joking or insulting remarks. Rader and I proved the cynosure of all eyes to the almost entire neglect of the Germans.

"Spy! spy!" they shouted at us.

"Kill the dirty beasts!" "You'll get what's coming to you-" etc.

Several men slashed their fingers across their throats, making a long, rasping sound at the same time, and then held their nose with one hand and pointed at us with the other. Another pointed a long, villainous looking knife at his stomach and began to laugh with wild glee. At last we had made our way through the long lines of the soldiers to the village itself, where an even worse reception awaited us from the embittered villagers. A double line of them lolled over to see us and proved even more insulting. Fortunately I did not understand all they said, and my companions understood nothing but the all too eloquent signs.

Finally, when it seemed we would never reach the end of that jeering, insulting crowd, we arrived at our destination. Hungry, thirsty, exhausted by lack of sleep and eleven miles' march under manacles, and chilled to the bone by rain and dripping clothes, we had about reached our limit. Nor does this include the tremendous humbleness of our spirits and a certain element of fear as to our fate. At last, however, we were unmanacled and the three Germans rushed off so quickly we did not have time to say good-bye to them. While awaiting in the entryway to a big courtyard, we succeeded in getting a little something to cat.

An Extemporized Cell

Then suddenly we were yanked off to headquarters. Down that same street by which we had entered, we now passed again, this time unmanacled, to the stable of the splendid house that served as headquarters, and Rader was put into one stall and myself into a very small tool-room. There at last we had come to rest.

It was a horrible place I found myself in.

An old couch with stiff hair bursting out in several places was backed up against one wail, while a small table and a whole lot of tools occupied most of the rest of the space. There was no room to walk about and I was forced either to lie on my couch or sit like a Buddha on the table.

By good luck I found a thin white blanket with many holes in it and a very doubtful past, to wrap about my drenched person. For three hours I sat in the inky blackness in my cold jail with the white blanket wrapped about me meditating on what a fool I was not to have followed the advice of the French gendarme and stayed at home.

Into the midst of my reveries came a guard to conduct me back to the splendid stall occupied by Rader. By now we had learned what the expression, "hit the hay," means, and we wasted no time in doing it. At last we had enough to keep ourselves decently warm and were able to dry our clothes and thaw out somewhat. A sick Moroccan, who showed almost no signs of life, breathed heavily beside me; and in the middle of the night a fool Frenchman lay down at our feet. I found him very useful to put my toes under to keep warm, for I had taken off my shoes in the hope of drying them, but as usual Rader killed the goose. He suddenly lengthened out in the night and brought his shoe with a crash like the falling of a heavy coconut against the skull of the Frenchman below. Wildly the Frenchman jumped to his feet like a jack-in-the-box and for several minutes flung himself around like a pin-wheel, shouting his head off over our prostrate semi-conscious forms till the whole building was awake. Then he left.

That next day was awful. Never before had I known the insanity of confinement. Immediately after a sunrise breakfast we were again separated and I was sent back to my Buddha's seat. There was nothing to read, nothing to do, not even a chance to walk. The dull rumble of the battle of the Aisne continued to come to us and occasionally a French aeroplane went overhead.

Along in the middle of the morning Rader's face appeared around the corner.

"Hey," he said, "I'm going crazy. Let's get out of here. Why don't you telegraph Ambassador Herrick?"

"Not a chance," I said. "We got ourselves into this mess, and now we have got to get ourselves out."

"Well, I'll telegraph then," he said.

You can't," I answered. " You don't speak French."

"Aw, that's what you always say," he retorted. " I don't have a chance here. I hate this beastly country."

"Well," I answered, "you wait a minute. I'll see what I can do. I'm going crazy, too."

I asked my guard to take me to the captain of the day. To my surprise he did so without question. I told the captain I was nothing but a poor, harmless, American newspaper man, whose greatest ambition in life was to get back to Paris and who was getting a little tired of living half-fed, soaked, and manacled in straw and horse stalls.

"Where did you come from? This is the first I've heard about you. Where are you staying? What are you doing here? Where did they get you?" he fired at me.

Briefly I told him I had been arrested back there a little way, not bothering to burden him with the fact that I had been caught on the firing line, and that at present I was living in a horse stall at the rear of his quarters. He set himself with vim to clear up the mystery, but it could not he done. The general and his staff, whose own particular prisoners we had been, had gone back to the front. The gendarmes who had brought us had returned to Pierrefonds. The guards who had received us had been sent out to the front that very morning at six o'clock. No written record could be found of us.

So the captain decided he would let us go. I pleaded with him to give us a pass to Paris, which he said was unnecessary. I told him that every time I had heard that before I had wound up in jail a few hours afterward, and that I didn't want to do any more first-hand investigating at this time. An English officer standing near by interjected the cheerful news that if he had caught me he would have put me in a fortress till the end of the war.

Finally, however, we got our pass, our possessions, our bicycles, and our liberty. The captain told us not to fool around getting back to Paris, but it was unnecessary front again. I had done that before and advice. We covered the ground as quickly as possible, by bicycle and by train. This time, however, I did not make the mistake of swearing that I would never go to the front again. I had done that before and found that it did not work.