- from the book

- 'Vive la France'

- by American journalist E. Alexander Powell 1916

The War in the Air

The Conflict in the Clouds

Dawn was breaking over the Lorraine hills when the French aircraft were wheeled from their canvas hangars and ranged in squadrilla formation upon the level surface of the plain. In the dim light of early morning the machines, with their silver bodies and snowy wings, bore an amazing resemblance to a flock of great white birds which, having settled for the night, were about to resume their flight. All through the night the mechanicians had been busy about them, testing the motors, tightening the guy-wires, and adjusting the planes, while the pilots had directed the loading of the explosives, for a whisper had passed along the line of sheds that a gigantic air-raid, on a scale not yet attempted, was to be made on some German town. At a signal from the officer in command of the aviation field the pilots and observers, unrecognizable in their goggles and leather helmets and muffled to the ears in leather and fur, climbed into their seats. In the clips beneath each aeroplane reposed three long, lean messengers of death, the torpedoes of the sky, ready to be sent hurtling downward by the pulling of a lever, while smaller projectiles, to be dropped by hand, filled every square inch in the bodies of the aeroplanes.

From somewhere out on the aviation field a smoke rocket shot suddenly into the air. It was the signal for departure. With a deafening roar from their propellers the great biplanes, in rapid succession, left the ground and, like a flock of wild fowl, winged their way straight into the rising sun. As they crossed the German lines at a height of twelve thousand feet the French observers could see, far below, the decoy aeroplanes which had preceded them rocking slowly from side to side above the German anti-aircraft guns in such a manner as to divert their attention from the raiders.

On an occasion like this each man is permitted the widest latitude of action. He is given an itinerary to which he is expected to adhere as closely as circumstances will permit, and he is given a set point at which to aim his bombs, but in all other respects he may use his own discretion. The raiders flew at first almost straight toward the rising sun, and it was not until they were well within the enemy's lines that they altered their course, turning southward only when they were opposite the town which was their objective. So rapid was the pace at which they were travelling that it was not yet six o'clock when the commander of the squadron, peering through his glasses, saw, far below him, the yellow gridiron which he knew to be the streets, the splotches of green which he knew to be the parks, and the squares of red and grey which he knew to be the buildings of Karlsruhe. The first warning that the townspeople had was when a dynamite shell came plunging out of nowhere and exploded with a crash that rocked the city to its foundations. The people of Karlsruhe were being given a dose of the same medicine which the Zeppelins had given to Antwerp, to Paris, and to London.

As the French airmen reached the town they swooped down in swift succession out of the grey morning sky until they were close enough to the ground to distinguish clearly through the fleecy mist the various objectives which had been given them. For weeks they had studied maps and bird's-eye photographs of Karlsruhe until they knew the place as well as though they had lived in it all their lives. One took the old grey castle on the hill, another took the Mar-grave's palace in the valley, others headed for the railway station, the arms factory, and the barracks. Then hell broke loose in Karlsruhe.

For nearly an hour it rained bombs. Not incendiary bombs or shrapnel, but huge 4-inch and 6-inch shells filled with high explosive which annihilated everything they hit. Holes as large as cellars suddenly appeared in the stone-paved streets and squares ; buildings of brick and stone and concrete crashed to the ground as though flattened by the hand of God; fires broke out in various quarters of the city and raged unchecked; the terrified inhabitants cowered in their cellars or ran in blind panic for the open country; the noise was terrific, for bombs were falling at the rate of a dozen to the minute ; beneath that rain of death Karlsruhe rocked and reeled. The artillery was called out but it was useless ; no guns could hit the great white birds which twisted and turned and swooped and climbed a mile or more overhead. Each aeroplane, as soon as it had exhausted its cargo of explosives, turned its nose toward the French lines and went skimming homeward as fast as its propellers could take it there, but to the inhabitants of the quivering, shell-torn town it must have seemed as though the procession of aircraft would never cease.

The return to the French lines was not as free from danger as the outward trip had been, for the news of the raid had been flashed over the country by wire and wireless and anti-aircraft guns were on the look-out for the raiders everywhere. The guarding aeroplanes were on the alert, however, and themselves attracted the fire of the German batteries or engaged the German Taubes while the returning raiders sped by high overhead. Of the four squadrillas of aeroplanes which set out for Karlsruhe only two machines failed to return. These lost their bearings and were surprised by the sudden rising of hawk-like Aviatiks which cut them off from home and, after fierce struggles in the air, forced them to descend into the German lines. But it was not a heavy price to pay for the destruction that had been wrought and the moral effect that had been produced, for all that day the roads leading out of Karlsruhe were choked with frantic fugitives and the stories which they told spread over all southern Germany a cloud of despondency and gloom. Since then the news of the Zeppelin raids on London has brought a thrill of fear to the people of Karlsruhe. They have learned what it means to have death drop out of the sky.

More progress has been made in the French air service, which has been placed under the direction of the recently created Subministry of Aviation, than in any other branch of the Republic's fighting machine. Though definite information regarding the French air service is extremely difficult to obtain, there is no doubt that on December I, 1915, France had more than three thousand aeroplanes in commission, and this number is being steadily increased. The French machines, though of many makes and types, are divided into three classes, according to whether they are to be used for reconnaissance, for fire control, or for bombardment. The machines generally used for reconnaissance work are the Moranes, the Maurice Farmans, and a new type of small machine known as the "Baby" Nieuport. The last-named, which are but twenty-five feet wide and can be built in eight days at a cost of only six thousand francs, might well be termed the Fords of the air. They have an eighty horsepower motor, carry only the pilot, who operates the machine gun mounted over his head, and can attain the amazing speed of one hundred and twenty miles an hour. These tiny machines can ascend at a sharper angle than any other aeroplane made, it being claimed for them, and with truth, that they can do things which a large bird, such as an eagle or a hawk, could not do.

The machines generally used for directing artillery fire are either Voisins or Caudron biplanes. The Voisin, which carries an observer as well as a pilot, is armed with a Hotchkiss quick-firer throwing three-pound shells, being the only machine of its size having sufficient stability to stand the recoil from so heavy a gun. The Caudron, which likewise has a crew of two men, has two motors, each acting independently of the other. I was shown one of these machines which, during an observation flight over the German lines, was struck by a shell which killed the observer and demolished one of the motors; the other motor was not damaged, however, and with it the pilot was able to bring the machine and his dead companion back to the French lines. For making raids and bombardments the Voisin and Breguet machines have generally been used, but they are now being replaced by the giant triplane which has fittingly been called "the Dreadnought of the skies." This aerial monster, the last word in aircraft construction, has a sixty-three foot spread of wing ; its four motors generate eight hundred horse- power ; its armament consists of two Hotchkiss quick-firing cannon and four machine guns ; it can carry twelve men - though on a raid the crew consists of four-and twelve hundred pounds of explosive; its cost is six hundred thousand francs.

As a result of this extraordinary advance in aviation, France has to-day a veritable aerial navy, formed in squadrons and divisions, with battleplanes, cruisers, scouts, and destroyers, all heavily armoured and carrying both machine guns and cannon firing three-inch shells. Each squadron, as at present formed, consists of one battleplane, two battle-cruisers, and six scout-planes, with a complement of upward of fifty officers and men, which includes not only the pilots and observers but the mechanics and the drivers of the lorries and trailers which form part of each outfit. These raiding squadrons are constantly operating over the enemy's lines, bombarding his bases, railway lines, and cantonments, hindering the transportation of troops and ammunition, and creating general demoralization behind the firing-line. On such forays it is the mission of the smaller and swifter machines, such as the Nieuports, to convoy and protect the larger and slower craft exactly as destroyers convoy and protect a battleship.

Two types of projectiles are carried on raiding aeroplanes ; aerial torpedoes, two, three, or four in number, fitted with fins, like the feathers on an arrow, in order to guide their course, which are held by clips under the body of the machine and can be released when over the point to be bombarded by merely pulling a lever ; and large quantities of smaller bombs, filled with high explosive and fitted with percussion fuses, which are dropped by hand. It is extremely difficult to attain any degree of accuracy in dropping bombs from moving aircraft, for it must be borne in mind that the projectiles, on being released, do not at once fall in a perfectly straight line to the earth, like a brick dropped from the top of a skyscraper. When an aeroplane is travelling forward at a speed of, let us say, sixty miles an hour, the bombs carried on the machine are also moving through space at the same rate. Owing to this forward movement combining with the downward gravitational drop, the path of the bomb is really a curve, and for this curve the aviator must learn to make allowance. Should the aircraft hover over one spot, however, the downward flight of the bomb is, of course, comparatively vertical.

The most exciting, as well as the most dangerous, work allotted to the aviators is that of flying over the enemy's lines and, by means of huge cameras fitted with telephoto lens and fastened beneath the bodies of the machines taking photographs of the German positions. As soon as the required exposures have been made, the machine speeds back to the French lines, usually amid a storm of bursting shrapnel, and the plates are quickly developed in the dark room, which is a part of every aerodrome. From the picture thus obtained an enlargement is made, and within two or three hours at the most the staff knows every detail of the German position, even to the depth of the wire entanglements and the number and location of the machine guns.

Should weather conditions or the activity of the enemy's anti-aircraft batteries make it inadvisable to send a machine on one of these photographic excursions, the camera is attached to a cerf volant, or war-kite. The entire equipment is carried on three motorcars built for the purpose, one car carrying the dismounted kite, the second the cameras and crew, while the third car is a dark room on wheels. I can recall few more interesting sights along the battle-front than that of one of these war-kites in operation. Taking shelter behind a farmhouse or haystack, the staff, in scarcely more time than it takes to tell about it, have jointed together the bamboo rods which form the framework of the kite, the linen which forms the planes is stretched into place, a camera with its shutter controlled by an electric wire is slung underneath, and the great kite is sent into the air. When it is over that section of the enemy's trenches of which a photograph is wanted, the officer at the end of the wire presses a button, the shutter of the camera swinging a thousand feet above flashes open and shut, the kite is immediately hauled down, a photographer takes the holder containing the exposed plate and disappears with it into the wheeled dark room to appear, five minutes later, with a picture of the German trenches.

The change that aeroplanes have produced in warfare is strikingly illustrated by the fact that in the Russo-Japanese War the Japanese fought for weeks and sacrificed thousands of men in order to capture 203-Metre Hill, not, mind you, because of its strategic importance, but in order that they might effectively control the fire of their siege mortars, which were endeavouring to reach the battleships in the harbour of Port Arthur. To-day that information would be furnished in an hour by aeroplanes. From dawn to dark aircraft hang over the enemy's positions, spotting his batteries, mapping his trenches, noting the movements of troops and trains, yet with a storm of shrapnel bursting about them constantly.

I remember seeing, in Champagne, a French aeroplane rocking lazily over the German lines, and of counting sixty shrapnel clouds floating about it at one time. So thick were the patches of fleecy white that they looked like the white tufts on a sky-blue coverlet. The shooting of the German verticals (anti-aircraft guns) has steadily improved as a result of the constant practice they have had, so that half the time there are ragged rents in the French planes caused by fragments of exploding shells. So deafening is the racket of the motor and propeller, however, that it is impossible to hear a shell unless it bursts at very close range, so that the aviators, intent on their work, are often utterly unconscious of how near they are to death. It is very curious how close shells can explode to a machine and yet not cripple it enough to bring it down. A pilot flying over the German lines in Flanders had his leg smashed by a bursting shell, which, strangely enough, did no damage to the planes or motor. The wounded man fainted from the pain and shock and his machine, left uncontrolled, began to plunge earthward. Recovering consciousness, the aviator, despite the excruciating pain which he was suffering, retained sufficient strength and presence of mind to get his machine under control and head it back for the French lines, though shrapnel was bursting all about him. He came quietly and gracefully to ground at his home aviation field and then fell over his steering lever unconscious.

No nervous man is wanted in the air service and the moment that a flier shows signs that his nerves are becoming affected he is given a furlough and ordered to take a rest. So great are the mental strain, the exposure, and the noise, however, that probably twenty-five per cent. of the aviators lose their nerve completely and have to leave the service altogether. The great French aviation school at Buc, near Paris, turns out pilots at the rate of one hundred and sixty a month. The first lessons are given on a machine with clipped wings, known as "the penguin," which cannot rise from the ground, and from this the men are gradually advanced, stage by stage, from machines as safe and steady and well-mannered as riding-school horses, until they at last become qualified pilots, capable of handling the quick-turning, uncertain-tempered broncos of the air. Provided he has sound nerves, a strong constitution, and average intelligence, a man who has never been in a machine before can become a qualified pilot in thirty days. Since the war began the French air service has attracted the reckless, the daring, and the adventurous from the four corners of the earth as iron filings are attracted by a magnet. Wearing on the collars of their silver-blue uniforms the gold wings of the flying corps are cow-punchers, polo-players, prize-fighters, professional bicycle riders, big game hunters, soldiers of fortune, young men who bear famous names, and other young men whose names are notorious rather than famous. In one squadrilla on the Champagne front I found a Texan cowboy and adventurer named Hall; Elliott Cowdin, the Long Island polo-player; and Charpentier, the heavyweight champion of France.

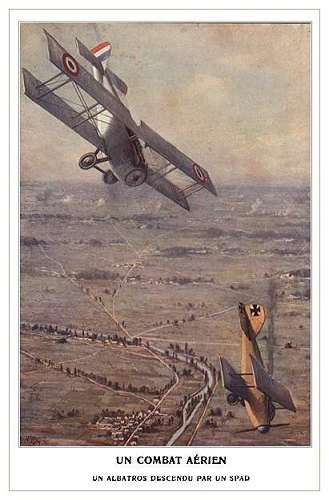

For youngsters who are seeking excitement and adventure, no sport in the world can offer the thrills of the chasse au Taube. To drive with one hand a machine that travels through space at a speed double that of the fastest express train and with the other hand to operate a mitrailleuse that spits death at the rate of a thousand shots a minute ; to twist and turn and loop and circle two miles above the earth in an endeavour to overcome an adversary as quick-witted and quick-acting as yourself, knowing that if you are victorious the victory is due to your skill and courage alone-there you have a game which makes all other sports appear ladylike and tame.

When an aeroplane armed with a mitrailleuse attacks an enemy machine the pilot immediately manoeuvres so as to permit the gunner observer to bring his gun into action. In order to make the bullets "spread" and ensure that at least some of the many shots get home, the gunner swings his weapon up and down, with a kind of chopping motion, so that, viewed from the front of the machine, the stream of bullets, were they visible, would be shaped like a fan. At the same time the gunner swings his weapon gently around, covering with a stream of lead the space through which his enemy will have to pass. Should the enemy machine be below the other, then to get clear he would possibly dive under his opponent in a sweeping turn. By this manoeuvre the gunner is placed in a position where he cannot bring his weapon to bear and he will have to turn in pursuit before his gun can be brought into action again. From this it will be seen that an aeroplane gunner does not take deliberate aim, as would a man armed with a rifle, but instead fills the air in the path of his opponent with showers of bullets in the hope that some of them will find the mark. Should both machines be armed with machine guns, as is now nearly always the case, victory is often a question of quick manoeuvring combined with a considerable element of luck. To win out in this aerial warfare, a man has to combine the quickness of a fencer with the coolness of a big game shot.

One of the greatest dangers the military aviator has to face is landing after night has fallen. Though every machine has a small motor, worked by the wind, which generates enough power for a small searchlight, the light is not sufficiently powerful to be of much assistance in gauging the distance from the ground. Sunset is; therefore, always an anxious time on the aviation fields, nor is the anxiety at an end until all the fliers are accounted for. As the sun begins to sink into the West the returning aviators one by one appear, black dots against the crimson sky. One by one they come swooping down from the heavens and come to rest upon the ground. Twilight merges into dusk and dusk turns into darkness, but one of the flying men has not yet come. The four corners of the aviation field are marked with great flares of kerosene, that the late comer may be guided home, and down the middle of the field lanterns are laid out in the form of a huge arrow with the head pointing into the wind, while search-lights, mounted on motor- cars, alternately sweep field and sky with their white beams. Anxiety is written plainly on the face of every one. Have the Boches brought him down ? Has he lost his way ? Or has he been forced from engine trouble or lack of petrol to descend elsewhere - " Hark ! " exclaims some one suddenly. "He's coming!" and in the sudden hush that ensues you hear, from somewhere in the upper darkness, a motor's deep, low throb.

The vertical beams of the searchlights fall and flood the level plain with yellow radiance. The hum of the motor rises into a roar and then, when just overhead, abruptly stops, and down through the darkness slides a great bird which is darker than the darkness and settles silently upon the plain.

The last of the chickens has come home to roost.

In addition to the aeroplanes kept upon the front for purposes of bombardment, photo- graphy, artillery control, and scouting, several squadrillas are kept constantly on duty in the vicinity of Paris and certain other French cities for the purpose of driving off marauding Taubes or Zeppelins. Just as the streets of Paris are patrolled by gendarmes, so the air-planes above the city are patrolled, both night and day, by guarding aeroplanes. To me there was something wonderfully inspiring in the thought that all through the hours of darkness these aerial watchers were sweeping in great circles above the sleeping city, guarding it from the death that comes in the night. For the benefit of my American readers I may say that the people of the United States do not fully understand the Zeppelin raid problem with which those entrusted with the defence of Paris and of London are confronted. The Zeppelins, it must be remembered, never come out unless it is a very dark night, and then they pass over the lines at a height of two miles or more, descending only when they are above the city which they intend to attack. They slowly, silently settle down until their officers can get a view of their target and then the bombs begin to drop.

This is usually the first warning that the townspeople have that Zeppelins are abroad, though it occasionally happens that they have been seen or heard crossing the line's, in which case the city is warned by telephone, the anti-aircraft guns prepare for action, and the lights in the streets and houses are put out. Should the Zeppelins succeed in getting above the city, the guarding aeroplanes go up after them and as soon as the searchlights spot them the guns open fire with shrapnel. The raiders are rarely fired on by the anti-aircraft guns while they are hovering over the city, however, as experience has shown that more people are killed by falling shell splinters than by the enemy's bombs. Nor do the French aeroplanes dare to make serious attacks until the Zeppelin is clear of the city, for it is not difficult to imagine the destruction that would result were one of these monsters, five hundred feet long and weighing thirty-six thousand pounds, to be destroyed and its flaming debris to fall upon the city. The problem that faces the French authorities, therefore, is stopping the Zeppelins before they reach Paris, and it speaks volumes for the efficiency of the French air service that there has been no Zeppelin raid on the French capital for nearly a year.

In order to detect the approach of Zeppelins the French military authorities have recently adopted the novel expedient of establishing microphone stations at several points in and about Paris, these delicately attuned instruments recording with unfailing accuracy the throb of a Zeppelin's or an aeroplane's propellers long before it can be heard by the human ear.

For the protection of London the British Government has built an aerial navy consisting of two types of aircraft-scouts and battle-planes. Practically the on]y requirement for the scouting planes is that they must have a speed of not less than one hundred miles an hour and a fuel capacity for at least a six-hour flight, thus giving them a cruising radius of three hundred miles. That is, they will be able to raid many German ports and cities and return with ease to their base in England. Their small size-they are only thirty feet across the wings-and great speed will make them almost impossible to hit and it is expected that anti-aircraft guns will be practically useless against them. They will constantly circle in the higher levels, as near the Zeppelin bases as they can get, and the minute they see the giants emerging from their hangars they will be off to England to give the alarm. Their speed being double that of a Zeppelin, they will have reached England long before the raider arrives. Then the new "Canada" type, each carrying a ton of bombs, will go out to meet the Germans. These giant biplanes, one hundred and two feet across the wings, with two motors developing three hundred and twenty horse- power, have a speed of more than ninety miles an hour and can overtake a Zeppelin as a motor-cycle policeman can overhaul a limousine. They are fitted with the new device for ensuring accuracy in bomb-dropping and, with their superior speed, will hang above the monster dirigibles, as a hawk hangs above a hen-roost, plumping shell after shell into the great silk sausage quivering below them.

Both the French and British Governments now have a considerable number of hydro- aeroplanes in commission. These amphibious craft, which are driven by two motors of one hundred and sixty horse-power each and have a speed of about seventy-five miles an hour, are designed primarily for the hunting of submarines. Though a submarine cannot be seen from the deck of a vessel, an aviator can see it even though it is submerged twenty feet, and a bomb dropped near it will cave its sides in by the mere force of the explosion, particularly if that bomb is loaded with two hundred pounds of melinite, as are those carried by the French hydro-aeroplanes.

But the most novel of all the uses to which the aircraft have been put in this war is that of dropping spies in the enemy's territory. On numerous occasions French and British aviators have flown across the German lines, carrying with them an intelligence officer disguised as a peasant or a farm-hand, and have landed him at some remote spot where the descent of an aeroplane is scarcely likely to attract the attention of the military authorities. As soon as the aviator has landed his passenger he ascends again, with the understanding, however, that he will return to the same spot a day, or two days, or a week later, to pick up the spy and carry him back to the French lines. The exploits of some of these secret agents thus dropped from the sky upon enemy soil would make the wildest fiction seem probable and tame. One French officer, thus landed behind the German front in Flanders, succeeded in slowly working his way right across Belgium, gathering information as he went as to the resources of the Germans and the disposition of their troops, only to be caught just as he was crossing the frontier into Holland. Though the Germans expressed unbounded admiration for his coolness, courage, and daring, he was none the less a spy. He died before the rifles of a firing- party.

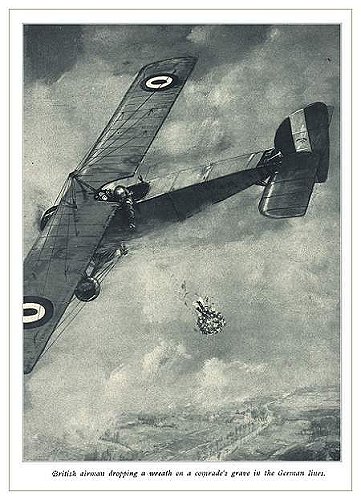

It has repeatedly been said that in this war the spirit of chivalry does not exist, and, so far as the land forces are concerned, this is largely true. But chivalry still exists among the fighters of the air. If, for example, a French aviator is forced to descend in the German lines, either because his machine has been damaged by gun-fire or from engine trouble, a German aviator will fly over the French lines, often amid a storm of shrapnel, and drop a little cloth bag which contains a note recording the name of the missing man, or if not his name the number of his machine, whether he survived, and if so whether he is wounded.

Attached to the "message bag" are long pennants of coloured cloth, which flutter out and attract the attention of the men in the neighbourhood, who run out and pick up the bag when it lands. It is at once taken to the nearest officer, who opens it and telephones the message it contains to aviation headquarters, so that it not infrequently happens that the fate of a flier is known to his comrades within a few hours after he has set out from the aviation field. Perhaps the prettiest exhibition of chivalry which the war has produced was evoked by the death of the famous French aviator, Adolphe Pegoud, who was killed by a German aviator whom he attacked during a reconnaissance near Petite Croix, in Alsace. The next day a German aeroplane, flying at a great height, appeared over Chavannes, an Alsatian village on the old frontier, where Pegoud was buried, and dropped a wreath which bore the inscription: "To Pegoud, who died like a hero, from his adversary."