An Interlude to War

Christmas Truce in the Trenches

Christmastide found the British Army becoming accustomed to the stagnation of a winter campaign in sodden Flanders.

On Christmas Eve, at midnight, the Germans in the trenches in front of the Ploegsteert Wood began to sing Christmas songs in chorus. The Somersets faced them. Some of the Somersets were old acquaintances of mine. Theirs was the first infantry command, with the Inniskillings and the Rifle Brigade, to arrive at the Ploegsteert Wood in the autumn, when the 1st Cavalry Division was fighting hard to hold the position.

A couple of Somerset bandsmen, who had left their instruments in England and were assigned to stretcher-gearing, told me a day or so after Christmas what occurred at Ploegsteert on Christmas Day.

The Saxon Christmas songs of the night before had odd results.

"The songs was fine," one of my informants declared. "They sang a lot. But the best was to come. A German bloke had a cornet, and he could play it grand. He just made it talk. The songs and the tunes the cornet feller played seemed more and more like ones we knew. Some of the songs I could have sung myself. At last out came that cornet with 'Home, Sweet Home,' and nobody could keep still. We all sang-Huns, English and all." The night spent in song produced a general peacefulness of spirit all round. As day broke the Somersets saw the Saxons on top of their trenches. Soon they called out, "Come over and visit us, we are Saxons." No shots were fired.

"None of our chaps started for the German trenches," continued the bandsman. "We had heard all about the white flags the Bosches had fired from under and all that. But our medical orfficer is a funny cove, and he got an idea in his head that started the whole thing. He said he saw a chance to give a burial to some of our dead that had been lyin' between trenches no end of a while.

"So he told me and my pal here to follow him, and afore we knew where he was goin', up he pops on the trench parapet. The Bosche trenches was only fifty to seventy yards in front, and up we had to get and over after that doctor. The Saxons was right there, in plain sight. I never sweat so, nor never did my pal here. We was sure there was a game on, and we would get it good as soon as we was well out of cover. Some of our dead had laid out there for eight or ten weeks, and was in a awful state. We picked up a Inniskillin orfficer, a captain, and got him on a stretcher-a big job-and got him back all right. No one fired a single shot.

"So out that doctor sends us again. We got over near the Bosche trench and up jumps a stocky little heavy-set German orfficer with a bushy black beard.

"He steps forward and says rough-like, with a scowl like he was goin' to eat us, 'Get back to your trenches, we have had quite enough of you. Get back there at once.'

"He spoke English all right, he did. We didn't need no interpreter for him. His looks went with what he said, too. We went all right. And I won't forget goin', not in this 'ere life, you can bet. That few yards seemed a sinful long way. Every step I thought 'Now I'll get it, right in the back,' but I didn't.

"We got into our trench right by our major in command, and told him what old whiskers had said and how he said it. All the major said was, 'I didn't think they would really let us get our dead. I'm not surprised.

'But that little trip of the doctor's had fair started it. Half an hour later I could see some of our lads on our right going right over to the Bosches in the open. The major saw 'em, too. When he got 'em in his eye he said, 'You can go on now, you men, and get some more of those dead in.

"We went. We never saw the black-bearded chap any more, either. One of the Saxon fellers who spoke pretty good English sung out and said we could go right on with what we were doin'. He said all of us could bury dead till four o'clock, and they would, too. And sure enough they did get at it pretty soon afterward.

"Of course with us all kicking round each other out there in the open, lots of chaps got to talkin'. The Saxons was friendly enough.

"One chap said to me, 'You Anglo-Saxons, we Saxons. We not want to fight you.

"I thought I'd land him one, so I said 'What about the Kayser, then, old lad? What do you think of Mr. Kayser, eh?

"'Bring him here, and we'll shoot him for you,' said the Saxon feller, and we all laughed.

"But I didn't take no stock of that. I knew he was only trying to be pleasant.

"Some of our chaps changed cigars and cigarettes. with them Huns, and had talks about all sorts of things. At four o'clock we' all took cover on both sides, but there was no firing on our front that night. The next morning we kept up the callin' business. We didn't stop it for a matter of eight days.

"Then the Saxons was relieved by the Bavarians. The Saxons warned us agin them Bavarians."

"One of the Saxon blokes said to one of our sergeants, 'Saxons do not like Bavarians. Shoot them like hell.'

"There was one Saxon chap, off a bit to our left, I heard one of our lot tell about that wouldn't have no truce. He was in front of the Rifle Brigade. He kept hammerin' away all through the piece, no matter what the Saxon chaps in front of us did."

An exchange of rations was a frequent occurrence during that remarkable period. Both sides agreed that tinned "bully" had no serious rival.

"Would the men who made friends with the Saxons fight them as hard afterwards?" I asked.

"Sure," was the reply. "If our chaps got a chance to put the bayonet home in one of those fellers, there wouldn't be no difference in the way they would do the job. All the first moves come from them, not from us. They even said they would fire high if they got orders to fire on us. We didn't make no such foolish promise.

"Our lot wanted to see the German trenches bad. They wouldn't let us right in, but we saw a lot and learned a lot. We could get right up to their wire, which was no end better than ours. But it ain't now. Wait till they try goin' against our wire, and they will find we learned a thing or two." And the little group chuckled in anticipation.

The most amusing conclusion to this Christmas truce, in its various phases here and there along the facing lines of trenches, was the trio of severe orders promulgated from three high Headquarters.

Sir John French's order was short and sharp, but very much to the point. It expressed great displeasure at such carryings-on.

General Joffre issued an order not a whit less severe in condemnation of such tendencies.

But fiercest of all, and threatening direst penalties, was the order issued by the Kaiser. That all three orders were necessary might give food for thought to psychologists.

That they were issued should, in kindness, have been told to Henry Ford.

from 'the illustrated War News' January 20th 1915 edition : photos of the Christmas Truce.

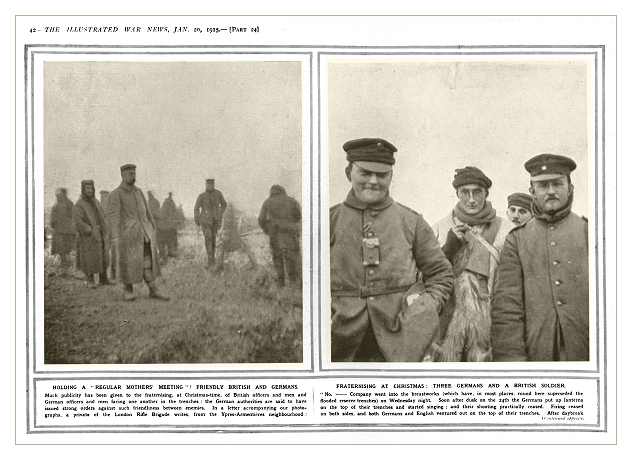

Caption of the Above Photograph

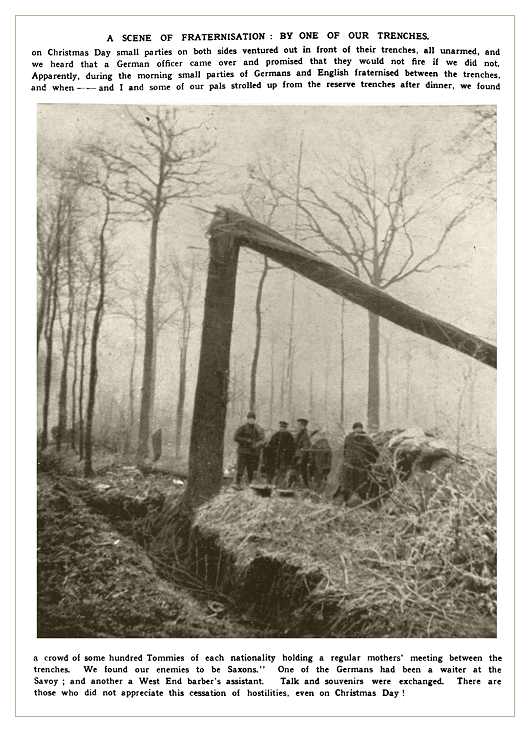

A Scene of Fraternisation : By One of Our Trenches

"Much publicity has been given to the fraternising, at Christmas-time of British officers and men and German officers and men facing one another in the trenches: the German authorities are said to have issued strong orders against such friendliness between enemies. In a letter accompanying our photographs, a private of the London Rifle Brigade writes, from the Ypres-Armentieres neighborhood : "No. ... Company went into the breastworks (which have, in most places, round here superseded the flooded reserve trenches) on Wednesday night. Soon after dusk on the 24th the Germans put up lanterns on the top of their trenches and started singing; and their shooting practically ceased. Firing ceased on both sides, and both Germans and English ventured out on the top of their trenches. After daybreak on Christmas Day small parties on both sides ventured out in front of their trenches, all unarmed, and we heard that a German officer came over and promised that they would not fire if we did not.

Apparently during the morning small parties of Germans and English fraternised between the trenches, and when ... and I and some of our pals strolled up from the reserve trenches after dinner, we found a crowd of some hundred Tommies of each nationality holding a regular mother's meeting btween the trenches. We found our enemies to be Saxons."

One of the Germans had been a waiter at the Savoy; and another a West-End barber's assistant. Talk and souvenirs were exchanged. There are those who did not appreciate this cessation of hostilities, even on Christmas Day !"

The author, Frederic Coleman, was an American and member of the (British) Royal Automobile Club who put himself and his motor-vehicle at the disposal of the British Army in August 1914. Attached as a motor-driver to General French's staff, in 1917 he published a book of memoires of his 1914 war-time experiences.