Animals Do Their Bit 3

The Animals Do Their Bit in the Great War

by Frank Hart

WITH THE HORSES, MULES, AND DONKEYS

Horses have always be-longed to Army life, and the trained troop-horse, that obeyed an order almost before it was given, was as old a hand as the old regular soldier; knowing his job through and through, with the addition, very often, of a few tricks as well. But to the others, legions of them, who were brought in at the call of War, soldiers' ways and military commands meant simply nothing at all.

They came from hunting stables, farmers' yards, private owners, and tradesmen's carts at first; but these were added to later, and more and more as the War lengthened out, by vast numbers from America, Canada, Australia, and, in fact, every possible corner of the earth in which horses could be raised. Most of them, too, were more or less wild, and with little or no training.

At the same time, many of the men who were to look after them, and with whom they were to be trained, had everything to learn themselves, and it became very largely a case of give and take on both sides; though sometimes, if the horse was wise enough, he trained the man.

One of the first things impressed on the soldier whose work will be connected with horses is that his charge or charges - for, if he is to become a "driver", he will have a pair of animals to look after-is that they must always come first, and that, however "done up" he may feel after a long day, they must be attended to before he thinks of what he would like to do for himself And this is right enough, because, for all their great strength in some ways, they are absurdly helpless in others, and rather like a lot of babies that must always be thought for.

Their meal-times, thrice daily, are full of excitement, all animals picketed in the same lines being fed at one and the same moment. There can be no feeding one here and another there, just because this Tommy may be ready and another one may not. There would be such a straining at the ropes and pawing up of the ground that heel-shackles and head-ropes would be breaking on all sides, allowing the horses to get loose in their impatience.

The animals have first to be watered, and are led off by their owners to the watering-place, which will probably be a long canvas trough fixed up as near the lines as possible. Meanwhile a corporal measures out the rations into the nose-bags, according to the condition or the amount of work that is being done by the various animals. By the time they are back from watering and are again tied in their places, the air will be filled with sundry neighings and impatient stamps of expectation, for the men are now all standing in rows down the lines behind the horses and with the nose-bags all ready. What they are waiting for is the word "FEED!" to be shouted down the lines by the N.C.O. in charge, as soon as he is satisfied that everybody is ready.

At the sound of' this order, there is an answering whinny on all sides, accompanied with neighs and gruntings of a much more satisfied note.

Mr. Atkins comes up from behind and buckles the nose-bags over his horses' heads noses being thrust in with such clumsy eagerness that there is a chance of some of the feed being spilt; a moment afterwards all the bustle and excitement seems to have suddenly ceased, and nothing can be heard but contented sounds of munching. The soldiers file off to their own meal,. while a picket of two or three only are left in the lines to take off the nose-bags as they are seen to be emptied, and to keep a sharp look-out lest any animal get loose.

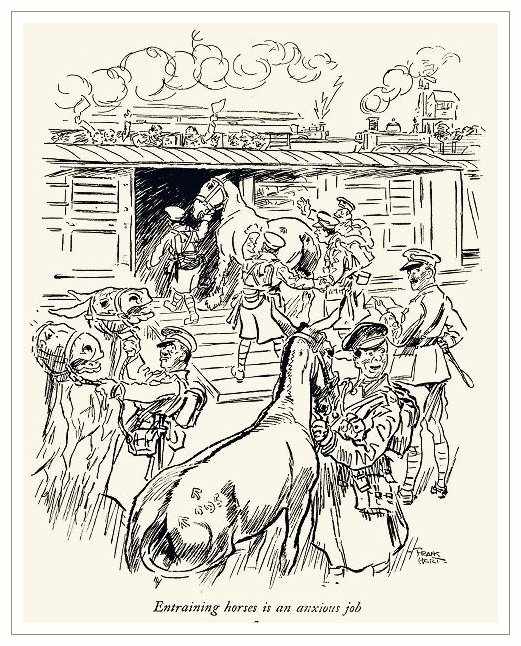

Getting horses on to trains or ships is an anxious affair; animals get scared or confused, hating to be taken out of their usual routine, and some of them have to be "persuaded" into the wagons. Sometimes a quiet horse will solve the problem by being led in first, and others will then follow, but there are usually one or two refusers". Entraining is an operation needing practice, and Tommy and his charges often get it, being hauled up at chance by night or day, thinking that at last they are off to the front in all seriousness. Orders and counter-orders come and go, feeds are put into nose-bags, harness is

looked to; fill equipment goes on with carefully filled water-bottles, and the horses are led out. Perhaps an hour or two, or more, and then more still, of tedious waiting has to be borne with, halting here, waiting there, until at last all is satisfactory. The horses are boxed, the wagons are on the trucks, when, hey presto! it has only been for practice. But at last we are really off to the front, and the times of "pretending" and mimic warfare are to be left behind.

Not that many of these animals will be engaged in actual fighting operations, such as those of the artillery; nor is there anything in their work carrying with it the glory and dash of a cavalry charge or encounter. It is mostly endless drudgery, carrying to and fro, though done often enough under exciting conditions. Field ambulances, with pairs or teams of horses or mules, carrying the sick and wounded men to the railhead for "Blighty", or to the base hospital; the convoy of wagons setting out by night in inky darkness to deliver rations and munitions, "dumping" their loads at the points from which they will be taken on by the pack-ponies, mules, and donkeys, as we shall see.

Certain parts of the convoy's road, too, will be considered "unhealthy", because the Huns will have marked it, training their artillery on to it by day to get the correct range, and shelling the road by night to try and destroy the convoy.

Come up now a little nearer to the neighbourhood of the trenches, closer yet to the actual perils of shot and shell. The animals are all in it, willy-nilly, sticking it out just like Mr. Atkins, only that whatever they may think about it all, they cannot, like him, make up for it by letting off steam in a good hearty grouse about everything and everybody, including the weather.

The group of small donkeys shown here, with their tins, and laden with baskets of rations, are French Colonials. Numbers of them were brought from Morocco and Algiers, to see if they could be used to relieve the soldiers of some of their work.

They are not so easily scared as their cousins the horses and mules, and being such small creatures they were not such a promising target if they were seen by the Huns. Getting food sent up by ration parties of men is a wearisome and dangerous job.

When the French tried using the humble little donkey, it was found that fifteen donkeys, with one soldier in charge, could carry up as much food as thirty men; so that even the donkeys have done their bit for France, and saved the lives of men.

Next we come to the work of the pack-ponies and the mules. They also carry rations", but mostly rations for the guns. They also bring up machine-guns and boxes of S.S.A., or small arms ammunition; and, as in the case of the donkey ration party, they have all the perils of the road to face.

Covered often to the ears with mud, maddened by noise and fumes from gas and shell, whipped and stung by driving rain and icy sleet, it is one long aching toil for man and beast, quite apart from the danger of being killed or wounded.