- from the book

- 'Vive la France !'

- by American Journalist E. Alexander Powell 1916

Fighting in Champagne

drawing of the fighting in Champagne from a popular 'Image d'Epinal'

THE FIGHTING IN CHAMPAGNE

WHEN the history of this war comes to be written, the great French offensive which began on September 25, 1915, midway between Rheims and Verdun, will doubtless be known as the Battle of Champagne. Hell holds no horrors for one who has seen that battlefield. Could Dante have walked beside me across that dreadful place, which had been transformed by human agency from a peaceful countryside to a garbage heap, a cesspool, and a charnel-house combined, he would never have written his "Inferno," because the hell of his imagination would have seemed colourless and tame. The difficulty in writing about it is that people will not believe me. I shall be accused of imagination and exaggeration, whereas the truth is that no one could imagine, much less exaggerate, the horrors that I saw upon those rolling, chalky plains.

In order that you may get clearly in your mind the setting of this titanic conflict, in which nearly a million and a half Frenchmen and Germans were engaged and in which Europe lost more men in killed and wounded than fought at Gettysburg, get out your atlas, and on the map of eastern France draw a more or less irregular line from Rheims to Verdun. This line roughly corresponds to the battle-front in Champagne. On the south side of it were the French, on the north the Germans. About midway between Rheims and Verdun mark off on that line a sector of some fifteen miles. If you have a sufficiently large-scale map, the hamlet of Auberive may be taken as one end of the sector and Massiges as the other. This, then, was the spot chosen by the French for their sledge-hammer blow against the German wall of steel.

There is scarcely a region in all France where a battle could have been fought with less injury to property. Imagine, if you please, an immense undulating plain, its surface broken by occasional low hills and ridges, none of them much over six hundred feet in height, and wandering in and out between those ridges the narrow stream which is the Marne. The country hereabouts is very sparsely settled; the few villages that dot the plain are wretchedly poor ; the trees on the slopes of the ridges are stunted and scraggly; the Soil is of chalky marl, which you have only to scratch to leave a staring scar, and the grass which tries to grow upon it seems to wither and die of a broken heart. This was the great manoeuvre ground of Chalons, and it was good for little else, yet only a few miles to the westward begin the vineyards which are France's chief source of wealth, and an hour's journey to the eastward is the beautiful forest of the Argonne.

Virtually, the entire summer of 1915 was spent by the French in making their preparations for the great offensive. These preparations were assisted by the extension of the British front as far as the Somme, thus releasing a large number of French troops for the operations in Champagne; by the formation of new French units; and by the extraordinary quantity of ammunition made available by hard and continuous work in the factories. The volume of preparatory work was stupendous. Artillery of every pattern and calibre, from the light mountain guns to the monster weapons which the workers of Le Creusot and Bourges and prophetically christened" Les Vainqueurs," was gradually assembled until nearly three thousand guns had been concentrated on a front of only fifteen miles. Had the guns been placed side by side they would have extended far beyond the fifteen-mile battle-front. There were cannon everywhere. Each battery had a designated spot to fire at and a score of captive balloons with telephonic connections directed the fire. One battery was placed just opposite a German redoubt which, the Germans boasted, could be held against the whole French army by two washerwomen with machine guns. Behind each of the French guns were stacked two thousand shells.

A network of light railways was built in order to get this enormous supply of ammunition up to the guns. From the end of the railway they built a macadamized highway, forty feet wide and nine miles long, straight as a ruler across the rolling plain. Underground shelters for the men were dug and underground stores for the arms and ammunition. The field was dotted with subterranean first-aid stations, their locations indicated by sign-boards with scarlet arrows and by the Red Cross flags flying over them. That the huge masses of infantry to be used in the attack might reach their stations without being annihilated by German shell-fire, the French dug forty miles of reserve and communication trenches, ten miles of which were wide enough for four men to walk abreast. Hospitals all over France were emptied and put in readiness for the river of wounded which would soon come flowing in. In addition to all this, moral preparation was also necessary, for it was a question whether the preceding months of trench warfare and the individual character it gives to actions had not affected the control of the officers over their men. Everything was foreseen and provided for; nothing was left to chance. The French had undertaken the biggest job in the world, and they set about accomplishing it as systematically, as methodically as though they had taken a contract to build a Simplon Tunnel or to dig a Panama Canal.

The Germans had held the line from Auberive to the Forest of the Argonne since the battle of the Marne. For more than a year they had been constructing fortifications and defences of so formidable a nature that it is scarcely to be wondered at that they considered their position as being virtually impregnable. Their trenches, which were topped with sand-bags and in many cases had walls of concrete, were protected by wire entanglements, some of which were as much as sixty yards deep. The ground in front of the entanglements was strewn with sharpened stakes and chevaux-de-frise and land mines and bombs which exploded upon contact. The men manning the trenches fought from behind shields of armour-plate and every fifteen yards was placed a machine gun. Mounted on the trench walls were revolving steel turrets, miniature editions of those on battleships, all save the top of the turret and the muzzle of the quick-firing gun within it being embedded in the ground.

The trenches formed a veritable maze, with traps and blind passageways and cul-de- sacs down which attackers would swarm only to be wiped out by skilfully concealed machine guns. At some points there were five lines of trenches, one behind the other, the ground behind them being divided into sections and supplied with an extraordinary number of communication trenches, protected by wire entanglements on both sides, so that, in case the first line was compelled to give way, the assailants would find themselves confronted by what were to all intents a series of small forts, heavily armed and communicating one with the other, thus enabling the defenders to rally and organize flank attacks without the slightest delay. This elaborate system of trenches formed only the first German line of defence, remember ; behind it there was a second line, the artillery being stationed between the two. There was, moreover, an elaborate system of light railways some of which came right up to the front connecting with the line from Challerange to Bazancourt, that there might be no delay in getting up ammunition and fresh troops from the bases in the rear.

No wonder that the Germans regarded their position as an inland Gibraltar and listened with amused complacence to the reports brought in by their aviators of the great preparations being made behind the French lines. Not yet had they heard the roar of France's massed artillery or seen the heavens open and rain down death.

On the morning of September 22 began the great bombardment - the greatest that the world had ever known. On that morning the French commander issued his famous general order "I want the artillery so to bend the trench parapets, so to plough up the dug-outs and subterranean defences of the enemy's line, as to make it almost possible for my men to march to the assault with their rifles at the shoulder."

It will be seen that the French artillerymen had their work laid out for them. But they went about it knowing exactly what they were doing. During the long months of waiting the French airmen had photographed and mapped every turn and twist in the enemy's trenches, every entanglement, every path, every tree, so that when all was in readiness the French were almost as familiar with the German position as were the Germans themselves. The first task of the French gunners was to destroy the wire entanglements, and when they finished few entanglements remained. The next thing was to bury the Germans in their dug-outs, and so terrific was the torrent of high explosive that whole companies which had taken refuge in their underground shelters were annihilated. The parapets and trenches had also to be levelled so that the infantry could advance, and so thoroughly was this done that the French cavalry actually charged over the ground thus cleared.

Then, while the big guns were shelling the German cantonments, the staff headquarters, and the railways by which reinforcements might be brought up, the field- batteries turned their attention to the communication trenches, dropping such a hail of projectiles that all telephone communication between the first and second lines was interrupted, so that the second line did not know what was happening in the first. There are no words between the covers of the dictionary to describe what it must have been like within the German lines under that rain of death. The air was crowded with the French shells. No wonder that scores of the German prisoners were found to be insane.

A curtain of shell-fire made it impossible for food or water to be brought to the men in the bombarded trenches, and made it equally impossible for these men to retreat. Hundreds of them who had taken refuge in their underground shelters were buried alive when the explosion of the great French marmites sent the earthen walls crashing in upon them. Whole forests of trees were mown down by the blast of steel from the French guns as a harvester mows down a field of grain. The wire entanglements before the German trenches were swept away as though by the hand of God. The steel chevaux-de-frise and the shields of armour-plate were riddled like a sheet of paper into which has been emptied a charge of buckshot. Trenches which it had taken months of painstaking toil to build were utterly demolished in an hour. The sand-bags which lined the parapets were set on fire by the French high explosive and the soldiers behind them were suffocated by the fumes. The bursts of the big shells were like volcanoes above the German lines, vomiting skyward huge geysers of earth and smoke which hung for a time against the horizon and were then gradually dissipated by the wind. For three days and two nights the bombardment never ceased or slackened. The French gunners, streaming with sweat and grimed with powder, worked like the stokers on a record-breaking liner. The metallic tang of the " soixante-quinze" and the deep- mouthed roar of the 120'S, the 155's, and the 370'S, and the screech and moan of the shells passing overhead combined to form a hurricane of sound. Conversation was impossible. To speak to a man beside him a soldier had to shout. Though the ears of the men were stuffed with cotton they ached and throbbed to the unending detonation.

An American aviator who flew over the lines when the bombardment was at its height told me that the German trenches could not be seen at all because of the shells bursting upon them. "The noise," he said, "was like a machine gun made of cannon." Imagine, then, what must have been the terror of the Germans cowering in the trenches which they had confidently believed were proof against anything and which they suddenly found were no protection at all against that rain of death which seemed to come from no human agency, but to be hellish in the frightfulness of its effect. When the bombardment was at its height the shells burst at the rate of twenty a second, forming one wave of black smoke, one unbroken line of exploding shells, as far as the horizon.

Graphic glimpses of what it must have been like in the German trenches during that three days' bombardment are given by the letters and diaries found on the bodies of German soldiers-written, remember, in the very shadow of death, some of them rendered illegible because spattered with the blood of the men who wrote them.

"The railway has been shelled so heavily that all trains are stopped. We have been in the first line for three days, and during that time the French have kept up such a fire that our trenches cannot be seen at all."

"The artillery are firing almost as fast as the infantry. The whole front is covered with smoke and we can see nothing. Men are dying like flies."

"A hail of shells is falling upon us. No food can be brought to us. When will the end come ? 'Peace ! ' is what every one is saying. Little is left of the trench. It will soon be on a level with the ground."

"The noise is awful. It is like a collapse of the world. Sixty men out of a company of two hundred and fifty were killed last night. The force of the French shells is frightful. A dug- out fifteen feet deep, with seven feet of earth and two layers of timber on top, was smashed up like so much matchwood."

When the reveille rang out along the French lines at five-thirty on the morning of September 25, the whole world seemed grey; lead-coloured clouds hung low overhead, and a drizzling rain was falling. But the men refused to be depressed. They drank their morning coffee and then, the roar of the artillery making conversation out of the question, they sat down to smoke and wait. Through the loopholes they could watch the effect of the fire of the French batteries, could see the fountains of earth and smoke thrown up by the bursting shells, could even see arms and legs flying in the air. Each man wore between his shoulders, pinned to his coat, a patch of white calico, in order to avoid the possibility of the French gunners firing into their own men. Several men in each company carried small, coloured signal-flags for the same purpose. The watches of the officers had been carefully synchronized, and at nine o'clock the order to fall in was given, and there formed up in the advance trenches long rows of strange fighting figures in their invisible pale-blue uniforms, their grim, set faces peering from beneath steel helmets plastered with chalk and mud. The company rolls were called. The drummers and buglers took up their positions, for orders had been issued that the troops were to be played into action ! The regimental battle-flags were brought from the dug-outs, the water-proof covers were slipped off, and the sacred colours, on whose faded silk were embroidered "Les Pyramides," "Wagram," “Jena," Austerlitz," “Marengo," were reverently unrolled.

For the first time in this war French troops were to go into action with their colours flying. Nine-ten! The officers, endeavouring to make their voices heard above the din of cannon, told the men in a few shouted sentences what France and the regiment expected of them. Nine-fourteen! The officers, having jerked loose their automatics, stood with their watches in their hands. The men were like sprinters on their marks, waiting with tense nerves and muscles for the starter's pistol. Nine-fifteen! Above the roar of the artillery the whistles of the officers shrilled loud and clear. The bugles pealed the charge. "En avant, les enfants! " screamed the officers, "En avant! Vaincre ou mourir!" and over the tops of the trenches, with a roar like an angry sea breaking on a rock-bound coast, surged a fifteen mile-long human wave tipped with glistening steel.

As the blue billows of men burst into the open, hoarsely cheering, the French batteries which had been shelling the German first-line trenches ceased firing with an abruptness that was startling. In the comparative quiet thus suddenly created could be plainly heard the orders of the officers and the cheering of the men, some of whom shouted "Vive la France!" while others sang snatches of the Marsellaise and the Carmagnole. Though every foot of ground over which they were advancing had for three days been systematically flooded with shell, though the German trenches had been pounded until they were little more than heaps of dirt and debris, the German artillery was still on the job, and the ranks of the advancing French were swept by a hurricane of fire. General Marchand, the hero of the famous incident at Fashoda, who was in command of the Colonials, led his men to the assault, but fell wounded at the very beginning of the engagement, as surrounded by his staff, he stood on the crest of a trench, cane in hand, smoking his pipe and encouraging the succeeding waves of men racing forward into battle. His two brigade-commanders fell close beside him. Three minutes after the first of the Colonials had scrambled over the top of their trenches they had reached the German first line. After them came the First and Second Regiments of the Foreign Legion and the Moroccan division. As they ran they broke out from columns of two (advancing in twos with fifty paces between each pair) into columns of squad (each man alone, twenty-five paces from his neighbour) as prettily and perfectly as though on a parade-ground.

Great as was the destruction wrought by the bombardment, the French infantry had no easy task before them, for stretches of wire entanglements still remained in front of portions of the German trenches, while at frequent intervals the Germans had left behind them machine-gun sections, who from their sunken positions poured in a deadly fire, until the oncoming wave overwhelmed and blotted them out. It was these death- traps that brought out in the French soldier those same heroic qualities which had enabled him, under the leadership of Napoleon, to enter as a conqueror every capital in Europe. A man who was shot while cutting a way for his company through the wire entanglements, turned and gave the cutters to a comrade before he fell. A wounded soldier lying on the ground called out to an officer who was stepping aside to avoid him: "Go on. Don't mind stepping on me. I'm wounded. It's only you who are whole who matter now." A man with his abdomen ripped open by a shell appealed to an officer to be moved to a dressing-station. "The first thing to move are the guns to advanced positions, my friend," was the answer.

"That's right," said the man; "I can wait.”

Said a wounded soldier afterward in describing the onslaught: "When the bugle sounded the charge and the trumpets played the Marseillaise, we were no longer mere men marching to the assault. We were a living torrent which drives all before it. The colours were flying at our side. It was splendid. Ay, my friend, when one has seen that one is proud to be alive."

In many places the attacking columns found themselves abruptly halted by steel chevaux-de-frise, with German machine guns spitting death from behind them. The men would pelt them with hand-grenades until the sappers came up and blew the obstructions away. Then they would sweep forward again with the bayonet, yelling madly. The great craters caused by the explosion of the French land mines were occupied as soon as possible and immediately turned into defensible positions, thus affording advanced footholds within the enemy's line of trenches. At a few points in the first line the Germans held out, but at others they surrendered in large numbers, while many were shot down as they were running back to the second line.

As a matter of fact, the Germans had no conception of what the French had in store for them, and it was not until their trenches began to give way under the terrible hammering of the French artillery that they realized how desperate was their situation. It was then too late to strengthen their front, however, as it would have been almost certain death to send men forward through the curtain of shell-fire which the French batteries were dropping between the first and second lines. Nor were the Germans prepared when the infantry attack began, as was shown by the fact that a number of officers were captured in their beds. The number of prisoners taken - twenty-one thousand was the figure announced by the French General Staff - showed clearly that they had had enough of it. They surrendered by sections and by companies, hundreds at a time. Most of them had had no food for several days, and were suffering acutely from thirst, and all of them seemed completely unstrung and depressed by the terrible nature of the French bombardment.

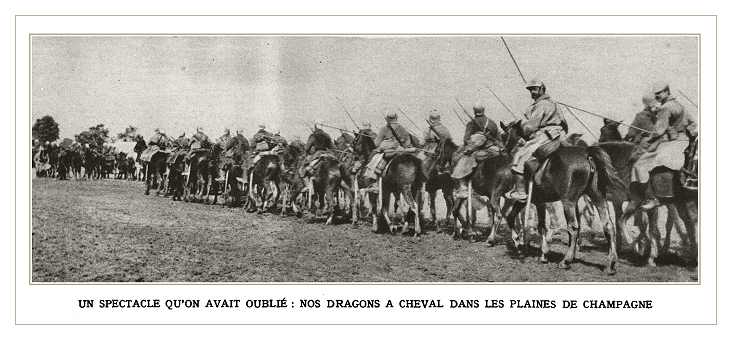

Choosing the psychological moment when, the retirement of the Germans showed signs of turning into panic, the African troops were ordered to go in and finish up the business with cold steel. Before these dark-skinned, fierce-faced men from the desert, who came on brandishing their weapons and shouting "Allah Allah ! Allah !” The Germans, already demoralized, incontinently broke and ran. Hard on the heels of the Africans trotted the dragoons and the chasseurs a cheval-the first time since the trench warfare began that cavalry have had a chance to fight from the saddle-sabring the fleeing Germans or driving them out of their dug-outs with their long lances. But in the vast maze of communication trenches and in the underground shelters Germans still swarmed thickly, so the " trench cleaners," as the Algerian and Senegalese tirailleurs are called, were ordered to clear them out, a task which they performed with neatness and despatch, revolver in one hand and cutlass in the other. Even five days after the trenches were taken occasional Germans were found in hiding in the labyrinth of underground shelters.

The thing of which the Champagne battlefield most reminded me was a garbage-heap. It looked and smelled as though all the garbage cans in Europe and America had been emptied upon it. This region, as I have remarked before, is of a chalk formation, and wherever a trench had been dug, or a shell had burst, or a mine had been exploded, it left on the face of the earth a livid scar. The destruction wrought by the French artillery fire is almost beyond imagining. Over an area as long as from Charing Cross to Hampstead Heath and as wide as from the Bank to the Marble Arch the earth is pitted with the craters caused by bursting shells as is pitted the face of a man who has had the small-pox. Any of these shell-holes was large enough to hold a barrel; many of them would have held a horse; I saw one, caused by the explosion of a mine, which we estimated to be seventy feet deep and twice that in diameter. In the terrific blast that caused it five hundred German soldiers perished. At another point on what had been the German first line I saw a yawning hole as large as the cellar of a good-sized apartment house. It marked the site of a German blockhouse, but the blockhouse and the men who composed its garrison had been blown out of existence by a torrent of 370-millimetre high-explosive shells.

The captured German trenches presented the most horrible sight that I have ever seen or ever expect to see. This is not rhetoric ; this is fact. Along the whole front of fifteen miles the earth was littered with torn steel shields and twisted wire, with broken waggons, bits of harness, cartridge-pouches, dented helmets, belts, bayonets-some of them bent double-broken rifles, field-gun shells and rifle cartridges, hand-grenades, aerial torpedoes, knapsacks, bottles, splintered planks, sheets of corrugated iron which had been turned into sieves by bursting shrapnel, trench mortars, blood-soaked bandages, fatigue-caps, entrenching tools, stoves, iron rails, furniture, pots of jam and marmalade, note-books, water-bottles mattresses, blankets, shreds of clothing, and; most horrible of all, portions of what had once been human bodies. Passing through an abandoned German trench, I stumbled over a mass of grey rags, and they dropped apart to disclose a headless, armless, legless torso already partially devoured by insects. I kicked a hobnailed German boot out of my path and from it fell a rotting foot. A hand with awful, outspread fingers thrust itself from the earth as though appealing to the passer-by to give decent burial to its dead owner. I peered inquisitively into a dug- out only to be driven back by an overpowering stench. A French soldier, more hardened to the business than I, went in with a candle, and found the shell-blackened bodies of three Germans. Clasped in the dead fingers of one of them was a postcard dated from a little town in Bavaria. It began : "My dearest Heinrich: You went away from us just a year ago to-day. I miss you terribly, as do the children, and we all pray hourly for your safe return-" The rest we could not decipher; it had been blotted out by a horrid crimson stain. Without the war that man might have been returning, after a day's work in field or factory, to a neat Bavarian cottage, with geraniums growing in the garden, and a wife and children waiting for him at the gate.

Though when I visited the battlefield of Champagne the guns were still roaring-for the Germans were attempting to retake their lost trenches in a desperate series of counter- attacks - the field was already dotted with thousands upon thousands of little wooden crosses planted upon new-made mounds. Above many of the graves there had been no time to erect crosses or headboards, so into the soft soil was thrust, neck downward, a bottle, and in the bottle was a slip of paper giving the name and the regiment of the soldier who lay beneath. In one place the graves had been dug so as to form a vast rectangle, and a priest, his cossack tucked up so that it showed his military boots and trousers, was at work with saw and hammer building in the centre of that field of graves a little shrine.

Scrawled in pencil on one of the pitiful little crosses I read : "Un brave - Emile Petit - Mort aux Champ d'Honneur - Priez pour lui."

Six feet away was another cross which marks the spot where sleeps Gottlieb Zimmerman, of the Wurtemberg Pioneers, and underneath, in German script, that line from the Bible which reads : "He fought the good fight."

Close by was still another little mound under which rested, so the headboard told me, Mohammed ben Hassen Bazazou of the Fourth Algerian Tirailleurs. In life those men had never so much as heard of one another. Doubtless they must often have wondered why they were fighting and what the war was all about. Now they rest there quietly, side by side, Frenchman and German and African, under the soil of Champagne, while somewhere in France and in Wurtemberg and in Algeria women are praying for the safety of Emile and of Gottlieb and of Mohammed.

During the three days that I spent upon the battlefield of Champagne the roar of the guns never ceased and rarely slackened, yet not a sign of any human being could I see as I gazed out over that desolate plain on which was being fought one of the greatest battles of all time. There were no moving troops, no belching batteries, no flaunting colours - only a vast slag-heap on which moved no living thing. Yet I knew that hidden beneath the ground all around me, as well as over there where the German trenches ran, men were waiting to kill or to be killed, and that behind the trench-scarred ridges at my back, and behind the low-lying crests in front of me, sweating men were at work loading and firing the great guns whose screaming missiles crisscrossed like invisible express trains overhead to burst miles away, perhaps, with the crash which scatters death. The French guns seemed to be literally every-where. One could not walk a hundred yards without stumbling on a skilfully concealed battery. In the shelter of a ridge was posted a battery of 155-milimetre monsters painted with the markings of a giraffe in order to escape the searching eyes of the German aviators and named respectively Alice, Fernande, Charlotte, and Maria. From a square opening, which yawned like a cellar window in the earth, there protruded the long, lean muzzle of an eight-inch naval gun, the breech

of which was twenty feet below the level of the ground in a gun-pit which was capable of resisting any high explosive that might chance to fall upon it. This marine monster was in charge of a crew of sailors who boasted that their pet could drop two hundred pounds of melinite on any given object thirteen miles away. But the guns to which the French owe their success in Champagne, the guns which may well prove the deciding factor in this war, are not the cumbersome siege pieces or the mammoth naval cannon, but the mobile, quick-firing, never-tiring, hard-hitting, seventy-fives," whose fire, the Germans resentfully exclaim, is not deadly but murderous.

The battlefield was almost as thickly strewn with unexploded shells, hand-grenades, bombs, and aerial torpedoes as the ground under a pine-tree is with cones. One was, in fact, compelled to walk with the utmost care in order to avoid stepping upon these tubes filled with sudden death and being blown to kingdom come. I had picked up and was casually examining what looked like a piece of broom-handle with a tin tomato-can on the end, when the intelligence officer who was accompanying me noticed what I was doing. "Don't drop that ! he exclaimed, "put it down gently. It's a German hand-grenade that has failed to explode and the least jar may set it off. They're as dangerous to tamper with as nitroglycerine." I put it down as carefully as though it were a sleeping baby that I did not wish to waken.

As the French Government has no desire to lose any of its soldiers unnecessarily, men had been set to work building around the unexploded shells and torpedoes little fences of barbed wire, just as a gardener fences in a particularly rare shrub or tree. Other men were at work carefully rolling up the barbed wire in the captured German entanglements, in collecting and sorting out the arms and equipment with which the field was strewn, in stacking up the thousands upon thousands of empty brass shell- cases to be shipped back to the factories for reloading, and even in emptying the bags filled with sand which had lined the German parapets and tying them in bundles ready to be used over again. They are a thrifty people, are the French. There was enough spoil of one sort and another scattered over the battlefield to have stocked all the curio- shops in Europe and America for years to come, but as everything on a field of battle is claimed by the Government nothing can be carried away. This explains why the brass shells that are smuggled back to Paris readily sell for ten dollars apiece, while for German helmets the curio dealers can get almost any price that they care to ask. As a matter of fact, it is against the law to offer any war trophies for sale or, indeed, to have any in one's possession.

What the French intend to do with the vast quantity of spoil which they have taken from the battlefields, heaven only knows. It is said that they have great storehouses filled with German helmets and similar trophies which they are going to sell after the war to souvenir collectors, thus adding to the national revenues. If this is so there will certainly be a glut in the curio market and it will be a poor household indeed that will not have on the sitting-room mantelshelf a German pickelhaube. After the war is over hordes of tourists will no doubt make excursions to these battlefields, just as they used to make excursions to Waterloo and Gettysburg, and the farmers who own the fields will make their fortune showing the visitors through the trenches and dug-outs at five francs a head.

The French officers who accompanied me over the battlefield particularly called my attention to a steel turret, some six feet high and eight or nine feet in diameter, which had been mounted on one of the German trench walls. The turret, which has a revolving top, contained a 50-millimetre gun served by three men. The French troops who stormed the German position found that the small steel door giving access to the interior of the turret was fastened on the outside by a chain and padlock. When they broke it open they found, so they told me, the bodies of three Germans who had apparently been locked in by their officers, and left there to fight and die with no chance of escape. I have no reason in the world to doubt the good faith of the officers who showed me the turret and told me the story, and yet - well, it is one of those things which seems too improbable to be true.

As I have already mentioned (p. 135) when I was in Alsace the French officers told me that they found in certain of the captured positions German soldiers chained to their machine guns. There again the inherent improbability of the incident leads one to question its truth. From what I have seen of the German soldier, I should say that he was the last man in the world who had to be chained to his gun in order to make him fight. Yet in this war so many wildly improbable, wholly incredible things have actually occurred that one is not justified in denying the truth of an assertion merely because it sounds unlikely.

One of the things that particularly impressed me during my visit to Champagne was the feverish activity that prevailed behind the firing-line. It was the busiest place that I have ever seen; busier than Wall Street at the noon-hour; busier than the Panama Canal Zone at the rush period of the Canal's construction.

The roads behind the front for twenty miles were filled with moving troops and transport-trains; long columns of sturdy infantrymen in mud-stained coats of faded blue and wearing steel casques which gave them a startling resemblance to their ancestors, the men-at-arms of the Middle Ages; brown-skinned men from North Africa in snowy turbans and voluminous burnouses, and black-skinned men from West Africa, whose khaki uniforms were brightened by broad red sashes and rakish red tarbooshes ; sun-tanned Colonial soldiery from Annam and Tonquin, from Somaliland and Madagascar, wearing on their tunics the ribbons of wars fought in lands of which most people have never so much as heard; Spahis from Morocco and the Sahara, mounted on horses as wiry and hardy as themselves ; Zouaves in jaunty fezes and braided jackets and enormous trousers ; sailors from the fleet, brought to handle the big naval guns, swaggering along with the roll of the sea in their gait ; cuirassiers, their steel breastplates and horse-tailed helmets making them look astonishingly like Roman horsemen; dragoons so picturesque that they seemed to be posing for a Detaille or a Meissonier ; field-batteries, pale blue like everything else in the French army, rocking and swaying. over the stones; cyclists with their rifles slung across their backs hunter-fashion; leather-jacketed despatch riders on panting motor- cycles ; post-offices on wheels ; telegraph offices on wheels butchers' shops on wheels; bakers' shops on wheels ; garages on wheels ; motor-buses, their tops covered with wire-netting and filled with carrier-pigeons ; giant searchlights ; water-carts drawn by patient Moorish donkeys whose turbaned drivers cursed them in shrill, harsh Arabic ; troop transport cars like miniature railway-coaches, each carrying fifty men; field- kitchens with the smoke pouring from their stovepipes and steam rising from the soup cauldrons; long lines of drinking-water waggons, the gift of the Touring Club de France; great herds of cattle and woolly waves of sheep, soon to be converted into beef and mutton, for the fighting man needs meat, and plenty of it; pontoon-trains; balloon outfits; machine guns ; pack-trains; mountain batteries; ambulances; world without end, amen.

Though the roads were jammed from ditch to ditch, there was no confusion, no congestion. Everything was as well regulated as the traffic is in the busiest London streets. If the roads were crowded, so were the fields. Here a battalion of Zouaves at bayonet practice was being instructed in the "haymaker's lift," that terrible upward thrust in which a soldier trained in the use of the bayonet can, in a single stroke, rip his adversary open from waist to neck, and toss him over his shoulder as he would a forkful of hay. Over there a brigade of chasseurs d'Afrique was encamped, the long lines of horses, the hooded waggons, and the fires with the cooking-pots steaming over them, suggesting a mammoth encampment of gypsies. In the next field a regiment of Moroccan tirailleurs had halted for the night, and the men, kneeling on their blankets, were praying with their faces turned toward Mecca. Down by the horse-lines a Moorish barber was at work shaving the heads of the soldiers, but taking care always to leave the little top-knot by means of which the faithful when they die, may be jerked to Paradise.

A little farther on the huge yellow bulk of an observation balloon - "les saucisses," the French call them - was slowly filling preparatory to taking its place aloft with its fellows, which, at intervals of half a mile, hung above the French lines, straining at their tethers like horses that were frightened and wished to break away. In whichever direction I looked, men were drilling or marching. Where all these hordes of men had come from, where they were bound, what they were going to do, no one seemed to know or, indeed, particularly to care. They were merely pawns which were being moved here and there upon a mighty chessboard by a stout old man in a general's uniform, sitting at a map-covered table in a farmhouse many miles away.

As we made our way slowly and laboriously toward the front across a region so littered with scraps of metal and broken iron and twisted wire that it looked like the ruins of a burned hardware store, we began to meet the caravans of wounded. Lying with white, drawn faces on the dripping stretchers were men whose bodies had been ripped open like the carcasses that hang in front of butchers' shops; men who had been blinded and will spend the rest of their days groping in darkness ; men smashed out of all resemblance to anything human, yet still alive; and other men who, with no wound upon them, raved and laughed and cackled in insane mirth at the frightful humour of the things that they had seen. Every house and farmyard for miles around was filled with wounded, and still they came streaming in, some hobbling, some on stretchers, some assisted by comrades, some bareheaded, with the dried blood clotted on their heads and faces, other with their gas-masks and their mud-plastered helmets still on. Two soldiers came by pushing 3-wheeled stretchers, on which lay the stiff, stark forms of dead men. The soldiers were whistling and singing, like men returning from a day's work well done, and occasionally one of them in sheer exuberance of spirits would send his helmet spinning into the air. Coming to a little declivity, they raced down it with their grisly burdens, like delivery boys racing with their carts. The light vehicles bumped and jounced over the uneven ground until one of the corpses threatened to fall off, whereupon the soldiers stopped and, still laughing, tied the dead thing on again. Such is the callousness begot by war.

Their offensive in Champagne cost the French, I have every reason to believe, very close to 110,000 men. The German casualties, so the French General Staff asserts, were about 140,000, of whom 21,000 were prisoners.

In addition the Germans lost 121 guns. Despite this appalling cost in human lives, the distance gained by the French was so small that it cannot be seen on the ordinary map. Yet to measure the effect of the French effort by the ground gained would be a serious mistake. Just as by the Marne victory the French stopped the invasion and ruined the original German plan, which was first to shatter France and then turn against Russia; and just as by the victory of the Yser they effectively prevented the enemy from reaching the Channel ports or getting a foothold in the Pas-de Calais, so the offensive in Champagne, costly as it was in human lives, fulfilled its double mission of holding large German forces on the western front and of demoralizing and wearing down the German army. It proved, moreover, that the Allies can pierce the Germans provided they are willing to pay the cost.

Darkness was falling rapidly when I turned my back on the great battlefield, and the guns were roaring with redoubled fury in what is known on the British front as "the Evening Hate " and on the French lines as "the Evening Prayer." As I emerged from the communication trench into the high road where my car was waiting I met a long column of infantry, ghostly figures in the twilight, with huge packs on their backs and rifles slanting on their shoulders, marching briskly in the direction of the thundering guns. It was the night-shift going on duty at the mills - the mills where they turn human beings into carrion.

see another contemporary magazine piece on the Champagne fighting : The French Defence in Champagne

another 'Image d'Epinal' showing a simplistic vision on warfare

- Great War generals never seemed to have reconciled themselves to the fact that

- horse-borne troops had become a thing of the past, no matter how inspiring they looked.