Master Writers Of The War

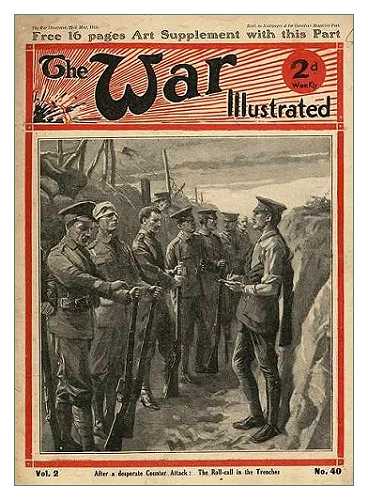

magazine covers from 'the War Illustrated'

Here in Are Shown the Perils of Preparation

If you had wandered along Devon Lane on Monday morning you would have arrived at the junction Number 23 Boyau—popularly known as "Fritz's Own" owing to the large number of dead Huns who graced it with their presence. You would have perceived Number 23 forking away left-handed to the front line thirty or forty yards ahead; you would have seen Devon Lane, under its new name of Number 22, doing the same thing towards the right. Only, as the wooden notice-boards conveying these mystic numbers had long ago been burnt for firewood, and the new tin ones had not arrived, all that you would really have perceived on Monday morning would have been the junction of two streams of liquid mud, lying stagnant and grey between their chalky walls. Here and there a few sandbags had fallen in, forming a sodden brown island at the bottom of the trench; here and there the decaying end of a trench-board sat up and laughed. If you stood on it the other end, working on the principle of a see-saw, arose and knocked you down; if you didn't stand on it, you drowned. Which all goes to show that it was an excellent spot to spend Monday morning.

Firmly gripping his waders with both hands as he took each step, an officer lucked his way along the morass until he reached the junction. Arrived there, he leaned against the side and carefully examined a trench-map which he produced from his pocket. Then once again he struggled on up the right-hand branch of the fork. He went perhaps twenty yards, and then he stopped, and cautiously peered over the side. His eyes searched the flat sea of dirt and desolation in the hope of spotting some landmark which would serve him as a guide for the job that had to be done that night. But the quest was hopeless, and after a moment or two he felt in his pocket for his compass. Taking off his steel helmet—for no compass can be used with one on—he made a rapid calculation.

"True bearing of the bally trench; one hundred and twenty degrees," he muttered. "Compass bearing—one hundred and thirty-two. That will bring us near that little mound, and------"

Ping-phat! With the agility of a young lamb the officer descended into the trench, and replaced his tin hat.

"Taking the air, sapper?" said a voice behind him, and the maker of calculations turned to find the second in command of the battalion holding the line grinning gently. "Methought I heard a little visitor up there."

"Of course, James," returned the sapper in pained surprise, "if your snipers are so singularly rotten that they allow the Hun to interrupt me in my work, no one can blame me if the assembly trench is laid out wrong."

"Is this where we start from?"

The major thoughtfully filled his pipe.

"A cheery trench to get a working-party up at night!" he continued. "Better to bring 'em up along the top. Our friend yonder will have calmed down by then." The sapper replaced his map. "But I'm thinking we'll have some casualties to-night."

And of all casualties perhaps the working-party ones are the most unsatisfactory. In an attack a man is up and doing; he is moving, and he has a chance of doing the killing himself. In a working-party, when the men are wiring or digging, it's a different matter. They are shot at, and they cannot shoot back; they are killed, and they cannot kill back. And yet without the working-party, without the trenches where the other men later may assemble before an assault, the attack is bound to fail. The dull preparations—out of the limelight—are as important as the final job—on the day. Such a little thing may cause such a big difference. A trench a few degrees out of the direction in which it should be may throw out the direction of one wave of the assaulting troops; may bring them askew on to their objective; may cause disaster. It is the same all through. One battalion will gain its objective with thirty casualties; the one next to it with six hundred. And the reason is one machine-gun in an unexpected place, or an officer's watch half a minute wrong. Mais—c'est la guerre.

“Go to your right, Sergeant Palmer. Get that tape two yards to your right." From Boyau 22 came the muttered orders to the N.C.O. who was standing on the top. Inside the boyau, with the compass laid carefully on the side to give the direction, stood the sapper officer. Glowing faintly in the darkness, the luminous patches on the lid of his instrument showed the bearing of one hundred and thirty-two degrees, which marked the direction in which the assembly trench had to be dug. Before the infantry working-party arrived, the white tracing tape which showed them in the darkness what they had to do must be stretched along the ground. It marked the front of the trench, and on it the men would be extended at a distance of two yards. Then—dig, and go on digging till the job is done.

"That's get it. Now carry on in that line. I'll check you every fifty yards." The sapper officer came out of the trench, and followed along behind his sergeant, who was running the tape off a stick. "Steady! Let's have a look at the direction now." With his compass in his hand he peered steadily at the white line on the ground. "Getting a little too much to the left, Palmer. Save the mark— where's that one going to?"

Both men watched with expert eyes the trail of sparks that shot up into the air from the German lines. It vas the outward and visible sign of the rum-jar—so called because of its likeness in appearance to that homely and delightful commodity. Except in appearance, however, the likeness was not great. The sparks continued for a while and then disappeared as the abomination reached its highest point of flight and started to descend. You can't see it—that's the devil of it. Yon know it's there—above you— somewhere; you know that in about two seconds, according to friend Newton's inexorable rule, it will no longer be above you. You also know that one second after it has become sociable, and returned out of the clouds, a great tearing explosion will shake the ground; bits of metal will ping like lost souls through the night; a cloud of stifling fumes will hang like a pall for a while—a cloud which will gradually drift away on the faint night breeze. Moreover, it always happens at the moment when you're waiting that you remember the poor devil who inadvertently went to ground in the same hole as the rum-jar, and who was finally identified by his boots.

"It's short, I think, sir," said the sergeant.

The officer did not answer. He was listening, waiting for the soft thud which would announce the arrival of the Hun's little message of love. Suddenly he heard it— ominously near. There was a faint swishing as the rum-jar came down through the sir, and then a squelching thud. As if actuated by a single string, the two men dived into a shell-hole and crouched, waiting.

"It's near, sir!" The sergeant just got out the words before it came. A shower of mud and water rained down on them, and the fumes drifting over left them coughing and spluttering. With a metallic ring a lump of metal hit the officer on his hat, and then once more silence reigned.

“Damned near! Far too damned near! If they're going to send over many of those, Palmer, we're going to have quite a cheery time. Where was it exactly?"

"Here, sir!" The N.C.O.'s voice came to him out of the darkness. "It's cut the tape."

Just one of the little things. Had they started from Boyau 22 a quarter of a minute after they did, that rum-jar would have bagged a bigger quarry than a piece of white tracing tape.

"Knot it together. We must be getting a move on, Palmer. The working-party will be here soon."

It was a quarter of an hour later, to be exact, that the two men retraced their footsteps along the tape towards Boyau 22. No more rum-jars had come to disturb them; only the great green flares had gone on continuously bobbing up into the night. From away to the south, where the horizon flickered and danced with the flashes of the guns, there came a ceaseless, monotonous rumble; but at Devon Lane all was peace. Everything was ready for the alteration of the landscape; only the actual performers, who would prepare fresh vistas for the beholders on Tuesday morning, were absent.

The sapper officer looked at his watch., "Very nicely timed, Palmer. I hope they're not late."

- Being a Further Episode from "the Assembly Trench"

- by "Sapper"

To those who are wont to think of war as an occupation teeming with excitement the digging of an assembly trench by a working-party will probably seem a singularly flat entertainment. And, in parenthesis, one may say that it is the heartfelt wish of all the performers that it will prove so.

Since work of that sort fills by far the greater part of the madness called war, and since the appetite for excitement of the death-or-glory type is more prevalent in stories than in reality, all that the average digger asks for is easy soil and a quick finish.

But let us labour under no delusions. There is room during the night's work for enough excitement to satisfy the veriest glutton; and though the occupation would not thrill crowded houses at the "movies" if it were filmed, it can be jumpy—deuced jumpy! Things do happen.

Everything was peaceful in Devon Lane as the sapper officer and his sergeant sat waiting for their working-party. Occasionally, by the light of a Verey flare, the white tracing-tape they had just laid out could be seen stretching away over the ground.

No further rum-jars had come to disturb the harmony of the evening; and, except for the muttering of the guns away south, there was silence.

Suddenly the metallic clang of a pick or a shovel made the sapper look up, and at the same moment a low voice hailed him.

"Are you there, sapper? The men are behind."

There is something oddly mysterious watching a party filing past in the darkness. The occasional creak of equipment, the heavy breathing of the men, the sudden curse as someone slips—all tend to help the illusion that one is watching some sinister deed.

They crowd on one out of the night, looming up in turn, and disappearing again into the darkness. Now and again, as a flare lights up everything, the whole line becomes motionless. Crouching, rigid, each man waits, with the green light shining on his face.

Away—right away—until one loses it in the night, runs the line of silent men. Just so many units—that's all; so many pawns in the great game. In a moment, when the darkness comes again, they will be passing on, these pawns, once more; they will have become dim shapes squelching by.

But just for that moment it's different. The human touch comes in; the man stooping beside one is an individual—not a pawn. Perhaps there's a smile on his face; perhaps there's a curse on his lips. Perhaps he's a stockbroker; perhaps he's a navvy.

But whatever he is, whatever he looks like, for the moment he is not a shape.

He is an individual; and he—that individual—may be the man to stop a stray bullet before the dawn. But then, for that matter, so may you. So what's the use of worrying anyway.

"Been quiet up to date?" The officer in charge of the working-party strolled slowly along the line of digging men with the sapper. The chink of a pick on a stone, the soft fall of the excavated earth, the dim line of figures bending and heaving, bending and heaving, silently and regularly, showed that the night's work had begun.

"A rum-jar unpleasingly close was the only excitement," returned the sapper. "But there's plenty of time yet, so don't despair."

"Gaw lumme!" A hoarse voice from just in front of them made them stop, and they saw one of the men peering into the hole where he was digging. "Gaw lumme! 'Erb, we've struck the blinking bag of nuts 'ere!"

The information apparently left 'Erb cold. "Wot's the matter?" he demanded. "Got a Fritz?"

"Not 'arf, I ain't! Damme! Ain't 'e a fair treat? 'Idden treasure ain't in it!"

But the two officers had not waited for further explorations. With due attention to the direction of the wind, they faded away, and left the proud discoverer to his own devices.

"How the devil," remarked the sapper, "some of these fellows can stand it I don't know! That Hun was guaranteed to make a Maltese goat unconscious at the range of a mile."

"I remember taking over a line once where the parapet was revetted with 'em," said the infantryman. "It's all a question of habit."

“And so is most of this war—a question of habit.” Where Death is such a common visitor, it stands to reason he loses much of his horror. If it were not so, men would go mad. But mercifully for them, a callousness numbs their sensibilities, and the dead are just part of the scenery. It will not last.

In time the crust will break away, and a man's outlook on life will become as it once was. The things that are happening over the water will seem to them then a dream, and the horror of that dream will be glossed over by the kindly hand of Time. Only a certain contempt of Death will remain—the legacy of their present mood.

"Clang!" The noise came distinctly in the two officers standing for a few minutes in Devon Lane.

"That's it!" said the infantryman irritably. "Let's have a brass band while we're at it. A machine-gun on this little lot, sapper, would be the deuce."

"There are a Jot of stray rifle-bullets coming across," remarked the other. "I wouldn't be surprised if that wasn't one of them getting busy."

They scrambled out of the trench, and even as they got on the top the order for stretcher-bearers came down the line.

"Who is it, Sergeant Ratcliffe?" said the infantryman.

"Don't know, sir. Someone up the other end, I think."

To be exact, it was 'Erb. There lies the impartiality of it all. It might have been the finder of the bag of nuts; it might have been any of the two hundred odd men stretched out along the tape. Just a stray, unaimed bullet loosed off by a sentry into the blue, and 'Erb had stopped it.

They found him lying on the ground, and because he was a man, and a big man, for all his shortness, he wasn't making a fuss. Just now and again he gave a little groan, and his feet drummed feebly on the ground. Around him there crouched three or four others, who, with clumsy gentleness, were trying to make the passing easier.

“Don't bunch, men." The infantryman's voice made them look up. "The stretcher-bearers are coming, so get on with your job."

He knelt down beside the dying man.

"Where were you hit, lad? They'll be here for you in a minute."

"No use this time, sir. I've blinking well copped it through the back!" His voice was feeble, and as he finished speaking he groaned and moved weakly.

“Lumme! And I was due for leave." The words trailed away into a whisper, and the officer, tending over him, caught a woman's name. Screening the light with his body, he flashed his torch for a moment on to the man's face. Then he stood up, and the sapper beside him saw him shake his head.

"None so dusty, Liza. You weren't much to look at—but"—once again he was silent—"it ain't fair, sir—it ain't fair—not altogether."

"What isn't, lad?" The officer belt over him.

"My cousin, sir. Ten pounds a week. Unmarried. Blarst him!"

Ten seconds later the stretcher-bearers arrived, but the soul of 'Erb had already started on the Great Journey. And if he went into the Valley with an oath on his lips, maybe the Judge is human. It ain't fair—not altogether------“

Such are the little thumbnail sketches of the game over the water. There are thousands similar, and yet each one is different—for each one is the tragedy of the individual to someone. The stretcher-bearers took him away, and later in one of the military cemeteries behind the line there will appear a cross, plain and unpretentious—"No. 1234 Private Herbert Musson. The Loamshires. R.I.P."

But that is later. At present all that matters is that 'Erb has copped it, and the blinking trench has got to be finished.

It's got to be used, that trench, in a few days. Men will have to sit there and wait. The shells will be screaming over them, the ground will be shaking—one of the show-pieces of war, beloved of the newspaper correspondent, will be about to start. And unless the trench has been finished, and finished correctly by the 'Erbs, the show-piece may fail.

So that if you regard 'Erb as a pawn, the price is not great. Unfortunately, to Liza he's an individual. And that is the tragedy of war.