- from ‘the War Illustrated', 11th December. 1915

- 'The Solace of Literature in the Trenches'

- by the Editor

The Observation Post

Of all the side-issues of this ever-more-surprising war few have been so unexpected as the immense demand for trench literature. We at home are not greatly to be blamed for having been found so unprepared for it, because it is sixty years since a British Army last had experience of trench warfare, and we could not have been expected to foresee that for weeks and months together our men would be living in caves and holes of the earth. We know that it was to the soldier's interest to travel light, and when seeing to his kit our thoughts were only of the irreducible minimum of weight compatible with the minimum of physical discomfort by-and-by. So we knitted him a Balaclava helmet to keep his head warm, and omitted to provide anything to supply the wants of the inside of his head. We remembered his stomach and forgot his brains. We thought long and anxiously about his food, and not at all about what used to be called mental pabulum.

This neglect on our part was due to ignorance of the conditions in which our Army was to find itself so soon. We were not so neglectful in the case of our Navy, for we knew that there would be many hours when our sailors would be free to amuse themselves, and we arranged to keep the Navy adequately supplied with newspapers and picture papers and illustrated magazines.

In the case of the Army we only thought of the newspapers, and those, of course, we arranged to post as regularly as might be. We could not know what life in the trenches would be like. Even so, however, we ought, perhaps to. have reflected that no such British Army had ever taken the field before, unlike all its predecessors not only in magnitude but also in composition; in the ranks of this astonishing force arc highly intellectual and educated men belonging to every social class and occupation—-professional, artistic, and commercial; it ought to have occurred to us that, whatever the conditions of warfare might be, there would probably be a good deal of time which they would be glad to have a book to fill.

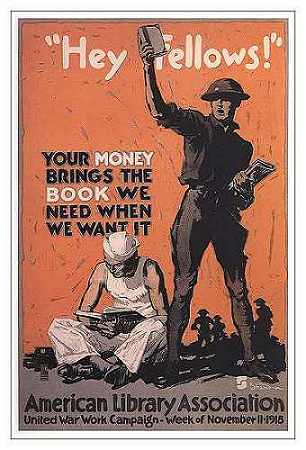

Thus we were caught unprepared by the clamour for books that rose from the trenches almost as soon as they had been dug. No matter what officer or man was asked if there was anything he wanted, the answer was always the same: cigarettes and something to read. Those articles headed every list of requirements however long it might be, and frequently they were the only things asked for. That the demand has been adequately and even generously met may be believed, but "something to read" is a very comprehensive phrase, and it has been interesting to inquire a little more closely into the question what Tommy does read in the trenches.

The first fact that emerges clearly is that he wants books that will distract his mind completely from his immediate environment. What he does not want is fiction about war; almost any other class of fiction he will look at, but it by no means follows that any other class will satisfy him. He will thank you for pure, unadulterated humour, and W. W. Jacobs has brought joy into many a trench. He likes tales of strong domestic interest, and it is worth noting that Jane Austen has taken her fragrant way into a surprising number of dug-outs. With regard to modern fiction, he requires it to be sound, wholesome stuff. He is face to face with elemental things—life, death, pain, heroism—and he has no use for artificiality and morbid imaginings, however brilliantly presented by meretricious cleverness. The men who come back from this war will do so with a very different idea of the values of things from that which they had when they marched out to it, and not a few authors will find it to their interest to take to heart the advice which Kingsley gave to the little maid, to be "good" and let who will be "clever."

Tommy in the trenches has a good deal of time to think about things that matter, and he is so interested in them that he does not much care for novels that don't matter; he will not thank you for sex problems, and studies of temperament, and "poppycock like that," nor will he be over much grateful for tales of adventure. His own present life is a most tremendously exciting, real adventure, and the fiction seems mild in comparison Romance, of course, is quite another matter, and Stevenson is free of the trenches. But the answer in respect of fiction is fairly clear: good humour, good domestic interest, good romance, are welcomed by the Army; they must be good, because the men have time and occasion to think.

The word takes one on to books that are not fiction, and it is found that essays, on life as distinct from literature, are passed from hand to hand. Bacon's "Essays" may be taken as typical—not least welcome, by the way, because they are all so short. There are plenty of writing men in the trenches, but they would not care just now for literary essays by literary men about literary subjects—Bagehot, say, or More, or Santayana; but Gissing's Henry Ryecroft is out there, no doubt because of its human interest and redolence of England. Sir Oliver Eodge is somewhere in France, too, and, one can well believe, taking thought in good direction. Of poetry and drama, Shakespeare, Palgrave's "Golden Treasury," and voyages by Alfred Noves appear to be popular.

The facts and the names given here have been gathered from conversation with a considerable number of men who have been in the trenches, and one conclusion can be drawn from them: a desirable quality in a book that is to be sent out is that it is available for the spare five minutes. Jacobs, Stevenson, Baton. Gissing, Lodge, Shakespeare, Palgrave's anthology, and Noyes. all satisfy this condition; so too does Jane Austen, though not so completely. And the five minutes' test goes -to prove the eminent suitability of The Times "Broadsheets," that have been edited and published expressly for the men in the trenches—short selections from the best literature issued in leaflet form. For another necessary feature a book for the trenches is that its format is small enough to go into a pocket. Truly the seven-penny is justified to-day.

We have heard, but not at first hand, of men reading the classics, apparently in the original, in the trenches, and among the hundreds of thousands of soldiers at the front it is not surprising that there should be some who occupy their leisure this way, or even in taking up a subject such as some branch of mathematics or learning a language. But it is rather to the internment camps that one must look for this kind of reading, to Ruhleben, for instance, where Francis Gribble, just released from that uncomfortable place, says classes were provided for the study of nearly every language—except German. In the trenches there is not time for the continuous concentration of mind that actual study requires; what is wanted there is the friendly companionship of some good and kindly book to take the mind away from the contemplation of the terrible environment, away from the sick longing for home, to the really vital things that comfort and sustain.

C. M.