An American Diplomat Views the Situation

“Antwerp had fallen, and the people of Brussels, as though stunned by some new and unexpected bereavement, stood in silent groups with solemn faces about the affiches on the walls, staring long at the brief announcement:

Les troupes allemandes sont entrées a Anvers cette après-midi.

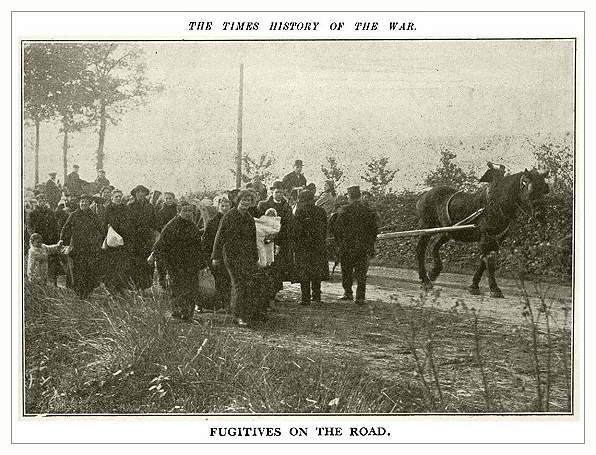

Then along the Antwerp road, open once more to travel, streamed the refugees - that strange, melancholy procession which unrolled in endless sequence its myriad obscure and anonymous tragedies For days and days the poor folk whom the war had driven out of that land, once so pleasant, between Brussels and Antwerp came pouring into the capital. The high road was crowded with them - miserable peasants with woebegone faces plodding stolidly on out of those stricken towns that had paid for the resistance of the Belgian army when it fell back from Liege on the fortified place of Antwerp. They had left behind their ruined villages and their vanished homes, and before them there lay they knew not what new sufferings, nor seemed any more to care. These were they who, unable to slip through the lines into Brussels, or over the border into Holland, or westward into the plains of Flanders or perhaps - strange and touching phenomenon-in the peasant's stubborn attachment to his own soil, had clung to their homes even when they lay in ruins about them. Then, driven out at last, they had hidden themselves in the heather and the bracken of the dreary Campine, or in the woods, in ravines, in fields, in ditches, anywhere they could find shelter, like hunted animals; and now that Antwerp was fallen they emerged and trailed their miseries along the road into Brussels. Some of those haggard eyes had looked on while Eppeghem was destroyed and had witnessed the dreadful deeds at Aerschot or at Boortmeerbeek, the horrors of Hofstade or of Sempst. The scattered throngs moved on, dumb, heavy, slow, without a word, without a cry, without a hope, beyond the power of expression or the need of it any more, treading a silent calvary of which no human means could voice the pain. There were men bent beneath their packs, and bowed under a far heavier load of despair; women with wan faces, whereon the stain of futile tears had long since dried, shawls over their heads, figures of utter misery; and children, their smiles gone, trotting in the mud beside their elders, glancing up now and then with that most terrible of all expressions the human countenance can assume - that look of terror in the eyes of little children who for the first time, in this our tragic life, realize that there are calamities which their mothers have no power to avert. The children clumped along in their sabots, which the Flemish onomatopoetically call ‘klompen’ the elder among them helping the younger, sometimes carrying them in their thin, pathetic arms.

Day after day and all through the night, in rain and mud and cold, in those drear October days of 1914, they trooped on with no place to go, without hope, almost without the will to hope. They trooped on in wooden shoes or in- no shoes at all, and they bore in their arms, or on their backs, their little all tied up in bundles. Some of them, the less unfortunate, had carts, and since they had no longer any patient dogs to draw them they patiently drew them themselves, straining against the ropes, their forms bowed in labour. Though it is, no doubt, a vicious habit to look at life through the eye of the artist and the writer, they reminded one of the figures in Laerman's pictures, and had all that pathos of toil with which Fr6d6ric has imbued his peasants.

Now and then, when some German officer- in arrogant indifference, muffled in the fur collar of his grey coat, swept by in his grey motor, or some detachment of soldiers, stolid and with brutish insensibility, marched along slavishly singing their songs, the refugees turned out into the ditches and waited, and when the soldiers had passed they climbed back on to the highway and plodded on again.

Twice I saw that pageant of human woe and misery organized to the glory of war: I saw it the first time in the glitter of an autumn sun; I saw it a week later - in the scumbled greys of a dismal day of rain, and I hope never to look upon the like again.

There were sights to see along the Antwerp road in those days: German troops coming back from the siege, with long trains of lumbering wagons filled with knapsacks and rifles, helmets, belts, sabres, all the salvage they had economically gathered; ruined villages like little Vilvorde, a spot sacred to the English-speaking race, for there William Tyndale was burned for having translated the Bible into our tongue; wrecks of houses, their windows broken in, their walls riddled with bullets or pierced by gaping shell-holes vomiting their debris into the street; and all the beautiful ash-trees that used to line the road felled to clear the way for cannon-ball - some, indeed, felled by the cannon-balls themselves. Near Eppeghem were the trenches the Belgians had abandoned, stretching across the yellow fields where asparagus (the famous asperges de Malines had been growing - the fields that had been so downy, so feathery; all trampled down in the rage that had seared them with its hot breath. In the little niches in the trench-walls there were crusts of mouldy bread, a tin cup, or a canteen; Belgian képis and knapsacks were strewn about; and in one place a subterranean room had been hollowed out, the garlands of paper flowers still on its clayey walls, and a table with matches, a lamp, a bottle, and the remains of the last supper-all as they had left it when at last they had to fly. And there was one sentient thing - a dog lying in one of the caverns; the poor fellow stared with great pathetic eyes but refused to come out, and lay there waiting for the master who would never more return.

Eppeghem was a silent place of ruins - not a roof remained, not a house that had not been ravaged by fire; the pretty grey old church but a heap of blackened stone and mortar. The body of a horse was lying in the street, its stiff legs sticking up in the air; hideous cats prowled among the ruins; and everywhere there were black bottles, thousands of them, emptied of their wine by the Germans in their guzzling.

It was so at Malines; empty bottles everywhere - ranged on window-sills, on doorsteps, or rolling in the street - evidence of an insatiable thirst. German soldiers, in. that ugly field-grey, were slinking out of houses hiding bottles under their tunics. The town was deserted of all, save now and then one saw some girl gathering bits of wood with which to make a fire, or a few women bent above the piles of debris, poking it over, trying to 'rescue something from the rubbish, all that remained to them.

The beautiful Grand' Place was but a heap of charred brick and twisted iron; and while the cathedral was standing, there were great holes yawning in its walls arid its carven stone was all broken, and every pane of the stained glass - all that remained of a beautiful lost art-was shattered to bits and quite gone, and its chimes, under the magic hand of Jeff Denyn, would sound their mellow peals across the fields no more. Near by, the grey old monastic residence of Cardinal Mercier stood with its roof beaten in.

Beyond, toward Antwerp, stood the fort of Waelhem, one of the outer defence - the key, I believe, to the pdsition. About, on every side, stretched the fields, gaunt and bare, sodden from their late inundation- every tree cut down - and intricate entanglements of barbed wire and chevaux de frise everywhere. Here and there was a new grave, with a wooden cross lettered in Flemish or in French; and just outside the fort, near the bridge across the moat, there was the grave of a German soldier, his rifle and his helmet laid upon it, with a few faded flowers. Evening was stealing over the fields from which the waters had not all receded ; there were pools here and there, gleaming in the slanting rays of the sun. There was the awful silence that follows cataclysm-as though not a living thing were left on earth, as though the end of the world had come.

The great mound of the grass-grown fort heaved itself above the wet level plain, the curve of its outline broken by the enormous hole that had been torn, like a crater, in its very summit by the shell of the ‘42’ that, in the deadly precision of the final and perfect shot, had blasted its steel cupola to bits. And there on the jagged summit the black, white, and red flag of modern Germany hung from its staff, and a sentinel stood beside it, solitary, immobile, his spiked helmet and his long bayonet outlined in sharp silhouette against the sky of faint, delicate rose, where the sun had set as though for the last time.

An hour before we had driven into Malines, and there by the ancient gate, the Porte de Bruxelles, an old peasant was sitting in the sun before the door of his ruined home; the light of day shone through the broken windows and the roof was gone. When he saw the little American flag on the motor he raised his hand in solemn salute. When we returned late in the afternoon there was the old peasant still sitting before the ruins of his home; he seemed not to have moved, but sat there in dumb despair, and he raised his hand again to his cap in that reverent salute. what did it mean to him, that bright bit of bunting with its fluttering red and white stripes and the white stars on the blue? What vague impressionistic dream of liberty and of justice did it evoke before those eyes that had gazed on nameless horrors and were beyond tears? I uncovered to him; I trust that he understood.

There along the roadside were the drab figures of the refugiés still bowed under their packs, still bending to the ropes with which they drew their carts; plodding on without complaint, without a word. The rain was falling tirelessly before the long, blinding rays of the headlights; the refugiés turned Out to let us pass. Now and then one of them, looking dumbly up and seeing the flag, touched his cap in salute. Then their figures became vague blurs in the rainy darkness…..”

From ‘Belgium Under the German Occupation, A Personal Narrative’ (1919) by Brand Whitlock, US Minister in Belgium during the Great War