- from the book ‘Golden Lads’

- 'Chantons Belges, Chantons!'

- by Arthur Gleason 1916

Belgium in the Great War

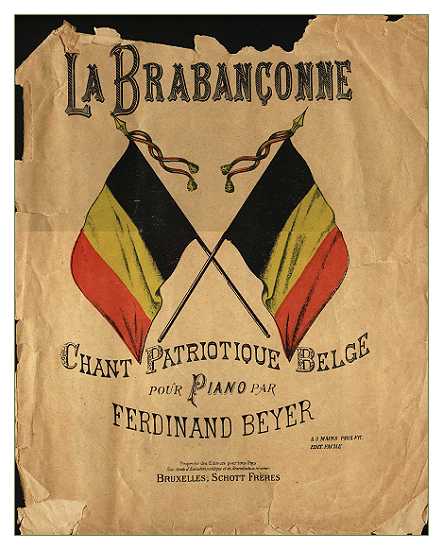

patriotic portrait of King Albert - sheet music for the Belgian national anthem

Chantons, Belges! Chantons!

Here at home I am in a land where the wholesale martyrdom of Belgium is regarded as of doubtful authenticity. We who have witnessed widespread atrocities are subjected to a critical process as cold as if we were advancing a new program of social reform. I begin to wonder if anything took place in Flanders. Isn't the wreck of Termonde, where I thought I spent two days, perhaps a figment of the fancy? Was the bayoneted girl child of Alost a pleasant dream creation? My people are busy and indifferent, generous and neutral, but yonder several races are living at a deeper level. In a time when beliefs are held lightly, with tricky words tearing at old values, they have recovered the ancient faiths of the race. Their lot, with all its pain, is choicer than ours. They at least have felt greatly and thrown themselves into action. It is a stern fight that is on in Europe, and few of our countrymen realize it is our fight that the Allies are making.

Europe has made an old discovery. The Greek Anthology has it, and the ballads, but our busy little merchants and our clever talkers have never known it. The best discovery a man can make is that there is something inside him bigger than his fear, a belief in something more lasting than his individual life. When he discovers that, he knows he, too, is a man. It is as real for him as the experience of motherhood for a woman. He comes out of it with self-respect and gladness.

The Belgians were a soft people, pleasure-loving little chaps, social and cheery, fond of comfort and the café brightness. They lacked the intensity of blood of unmixed single strains. They were cosmopolitan, often with a command over three languages and snatches of several dialects. They were easy in their likes. They "made friends" lightly. They did not have the reserve of the English, the spiritual pride of the Germans. Some of them have German blood, some French, some Dutch. Part of the race is gay and volatile, many are heavy and inarticulate; it is a mixed race of which any iron-clad generalization is false. But I have seen many thousands of them under crisis, seen them hungry, dying, men from every class and every region; and the mass impression is that they are affectionate, easy to blend with, open-handed, trusting.

This kindly, haphazard, unformed folk were suddenly lifted to a national self-sacrifice. By one act of defiance Albert made Belgium a nation. It had been a mixed race of many tongues, selling itself little by little, all unconsciously, to the German bondage. I saw the marks of this spiritual invasion on the inner life of the Belgians—marks of a destruction more thorough than the shelling of a city. The ruins of Termonde are only the outward and visible sign of what Germany has attempted on Belgium for more than a generation.

Perhaps it was better that people should perish by the villageful in honest physical death through the agony of the bayonet and the flame than that they should go on bartering away their nationality by piece-meal. Who knows but Albert saw in his silent heart that the only thing to weld his people together, honeycombed as they were, was the shedding of blood? Perhaps nothing short of a supreme sacrifice, amounting to a martyrdom, could restore a people so tangled in German intrigue, so netted into an ever-encroaching system of commerce, carrying with it a habit of thought and a mouthful of guttural phrases. Let no one underestimate that power of language. If the idiom has passed into one, it has brought with it molds of thought, leanings of sympathy. Who that can even stumble through the "Marchons! Marchons!" of the "Marseillaise" but is a sharer for a moment in the rush of glory that every now and again has made France the light of the world? So, when the German phrase rings out, "Was wir haben bleibt Deutsch"—"What we are now holding by force of arms shall remain forever German" — there is an answering thrill in the heart of every Antwerp clerk who for years has been leaking Belgian government gossip into German ears in return for a piece of money. Secret sin was eating away Belgium's vitality—the sin of being bought by German money, bought in little ways, for small bits of service, amiable passages destroying nationality. By one act of full sacrifice Albert has cleared his people from a poison that might have sapped them in a few more years without the firing of one gun.

That sacrifice to which they are called is an utter one, of which they have experienced only the prelude. I have seen this growing sadness of Belgium almost from the beginning. I have seen thirty thousand refugees, the inhabitants of Alost, come shuffling down the road past me. They came by families, the father with a bag of clothes and bread, the mother with a baby in arms, and one, two, or three children trotting along. Aged women were walking, Sisters of Charity, religious brothers. A cartful of stricken old women lay patiently at full length while the wagon bumped on. They were so nearly drowned by suffering that one more wave made little difference. All that was sad and helpless was dragged that morning into the daylight. All that had been decently cared for in quiet rooms was of a sudden tumbled out upon the pavement and jolted along in farm-wagons past sixteen miles of curious eyes. But even with the sick and the very old there was no lamentation. In this procession of the dispossessed that passed us on the country road there was no one crying, no one angry.

I have seen 5000 of these refugees at night in the Halle des Fêtes of Ghent, huddled in the straw, their faces bleached white under the glare of the huge municipal lights. On the wall, I read the names of the children whose parents had been lost, and the names of the parents who reported a lost baby, a boy, a girl, and sometimes all the children lost.

A little later came the time when the people learned their last stronghold was tottering. I remember sitting at dinner in the home of Monsieur Caron, a citizen of Ghent. I had spent that day in Antwerp, and the soldiers had told me of the destruction of the outer rim of forts. So I began to say to the dinner guests that the city was doomed. As I spoke, I glanced at Madame Caron. Her eyes filled with tears. I turned to another Belgian lady, and had to look away. Not a sound came from them.

When the handful of British were sent to the rescue of Antwerp, we went up the road with them. There was joy on the Antwerp road that day. Little cottages fluttered flags at lintel and window. The sidewalks were thronged with peasants, who believed they were now to be saved. We rode in glory from Ghent to the outer works of Antwerp. Each village on all the line turned out its full population to cheer us ecstatically. A bitter month had passed, and now salvation had come. It is seldom in a lifetime one is present at a perfect piece of irony like that of those shouting Flemish peasants.

As Antwerp was falling, a letter was given to me by a friend. It was written by Aloysius Coen of the artillery, Fort St. Catherine Wavre, Antwerp. He died in the bombardment, thirty-four years old. He wrote:

Dear wife and children:

At the moment that I am writing you this the enemy is before us, and the moment has come for us to do our duty for our country. When you will have received this I shall have changed the temporary life for the eternal life. As I loved you all dearly, my last breath will be directed toward you and my darling children, and with a last smile as a farewell from my beloved family am I undertaking the eternal journey.

I hope, whatever may be your later call, you will take good care of my dear children, and always keep them in mind of the straight road, always ask them to pray for their father, who in sadness, though doing his duty for his country, has had to leave them so young.

Say good-by for me to my dear brothers and sisters, from whom I also carry with me a great love.

Farewell, dear wife, children, and family.

Your always remaining husband, father, and brother.

ALOYS.

make-shift shelter for Belgian soldiers

Then Antwerp fell, and a people that had for the first time in memory found itself an indivisible and self-conscious state broke into sullen flight, and its merry, friendly army came heavy-footed down the road to another country. Grieved and embittered, they served under new leaders of another race. Those tired soldiers were like spirited children who had been playing an exciting game which they thought would be applauded. And suddenly the best turned out the worst.

Sing, Belgians, sing, though our wounds are bleeding, writes the poet of Flanders; but the song is no earthly song. It is the voice of a lost cause that cries out of the trampled dust as it prepares to make its flight beyond the place of betrayal.

For the Belgian soldiers no longer sang, or made merry in the evening. A young Brussels corporal in our party suddenly broke into sobbing when he heard the chorus of "Tipperary" float over the channel from a transport of untried British lads. The Belgians are a race of children whose feelings have been hurt. The pathos of the Belgian army is like the pathos of an orphan-asylum: it is unconscious.

They are very lonely, the loneliest men I have known. Back of the fighting Frenchman, you sense the gardens and fields of France, the strong, victorious national will. In a year, in two years, having made his peace with honor, he will return to a happiness richer than any that France has known in fifty years. And the Englishman carries with him to the stresses of the first line an unbroken calm which he has inherited from a thousand years of his island peace. His little moment of pain and death cannot trouble that consciousness of the eternal process in which his people have been permitted to play a continuing part. For him the present turmoil is only a ripple on the vast sea of his racial history. Behind the Tommy is his Devonshire village, still secure. His mother and his wife are waiting for him, unmolested, as when he left them. But the Belgian, schooled in horror, faces a fuller horror yet when the guns of his friends are put on his bell-towers and birthplace, held by the invaders.

"My father and mother are inside the enemy lines," said a Belgian officer to me as we were talking of the final victory. That is the ever-present thought of an army of boys whose parents are living in doomed houses back of German trenches. It is louder than the near guns, the noise of the guns to come that will tear at Bruges and level the Tower of St. Nicholas. That is what the future holds for the Belgian. He is only at the beginning of his loss. The victory of his cause is the death of his people. It is a sacrifice almost without a parallel.

And now a famous newspaper correspondent has returned to us from his motor trips to the front and his conversations with officers to tell us that he does not highly regard the fighting qualities of the Belgians. I think that statement is not the full truth, and I do not think it will be the estimate of history on the resistance of the Belgians. If the resistance had been regarded by the Germans as half-hearted, I do not believe their reprisals on villages and towns and on the civilian population would have been so bitter. The burning and the murder that I saw them commit throughout the month of September, 1914, was the answer to a resistance unexpectedly firm and telling. At a skirmish in September, when fifteen hundred Belgians stood off three thousand Germans for several hours, I counted more dead Germans than dead Belgians. The German officer in whose hands we were as captives asked us with great particularity as to how many Belgians he had killed and wounded. While he was talking with us, his stretcher-bearers were moving up and down the road for his own casualties. At Alost the street fighting by Belgian troops behind fish-barrels, with sods of earth for barricade, was so stubborn that the Germans felt it to be necessary to mutilate civilian men, women, and children with the bayonet to express in terms at all adequate their resentment. I am of course speaking of what I know. Around Termonde, three times in September, the fighting of Belgians was vigorous enough to induce the Germans on entering the town to burn more than eleven hundred homes, house by house. If the Germans throughout their army had not possessed a high opinion of Belgian bravery and power of retardation, I doubt if they would have released so wide-spread and unique a savagery.

At Termonde, Alost, Balière, and a dozen other points in the Ghent sector, and, later, at Dixmude, Ramscappelle, Pervyse, Caeskerke, and the rest of the line of the Yser, my sight of Belgians has been that of troops as gallant as any. The cowards have been occasional, the brave men many. I still have flashes of them as when I knew them. I saw a Belgian officer ride across a field within rifle range of the enemy to point out to us a market-cart in which lay three wounded. On his horse, he was a high figure, well silhouetted. Another day, I met a Belgian sergeant, with a tousled red head of hair, and with three medals for valor on his left breast. He kept going out into the middle of the road during the times when Germans were reported approaching, keeping his men under cover. If there was risk to be taken, he wanted first chance. My friend Dr. van der Ghinst, of Cabour Hospital, captain in the Belgian army, remained three days in Dixmude under steady bombardment, caring unaided for his wounded in the Hospital of St. Jean, just at the Yser, and finally brought out thirty old men and women who had been frightened into helplessness by the flames and noise. Because he was needed in that direction, I saw him continue his walk past the point where fifty feet ahead of him a shell had just exploded. I watched him walk erect where even the renowned fighting men of an allied race were stooping and hiding, because he held his life as nothing when there were wounded to be rescued. I saw Lieutenant Robert de Broqueville, son of the prime minister of Belgium, go into Dixmude on the afternoon when the town was leveled by German guns. He remained there under one of the heaviest bombardments of the war for three hours, picking up the wounded who lay on curbs and in cellars and under debris.

The troops had been ordered to evacuate the town, and it was a lonely job that this youngster of twenty-seven years carried on through that day.

Belgian soldiers on the Yser front

I have seen the Belgians every day for several months. I have seen several skirmishes and battles and many days of shell-fire, and the impression of watching many thousand Belgians in action is that of excellent fighting qualities, starred with bits of sheer daring as astonishing as that of the other races. With no country left to fight for, homes either in ruin or soon to be shelled, relatives under an alien rule, the home Government on a foreign soil, still this, second army, the first having been killed, fights on in good spirit. Every morning of the summer I have passed boys between eighteen and twenty-five, clad in fresh khaki, as they go riding down the poplar lane from La Panne to the trenches, the first twenty with bright silver bugles, their cheeks puffed and red with the blowing. Twelve months of wounds and wastage, wet trenches and tinned food, and still they go out with hope.

And the helpers of the army have shown good heart. Breaking the silence of Rome, the splendid priesthood of Belgium, from the cardinal to the humblest curé, has played the man. On the front line near Pervyse, where my wife lived for three months, a soldier- monk has remained through the daily shell-fire to take artillery observations and to comfort the fighting men. Just before leaving Flanders, I called on the sisters in the convent school of Furnes. They were still cheery and busy in their care of sick and wounded civilians. Every few days the Germans shell the town from seven miles away, but the sisters will continue there through the coming months as through the last year. The spirit of the best of the race is spoken in what King Albert said recently in an unpublished conversation to the gentlemen of the English mission:

"The English will cease fighting before the Belgians. If there is talk of yielding, it will come from the English, not from us."

That was a playful way of saying that there will be no yielding by any of the Western Allies. The truth is still as true as it was at Liège that the Belgians held up the enemy till France was ready to receive them. And the price Belgium paid for that resistance was the massacre of women and children and the house-to-house burning of homes.

Since rendering that service for all time to France and England, through twenty months of such a life as exiles know, the Belgians have fought on doggedly, recovering from the misery of the Antwerp retreat, and showing a resilience of spirit equaled only by the Fusiliers Marins of France. One afternoon in late June my friend Robert Toms was sitting on the beach at La Panne, watching the soldiers swimming in the channel. Suddenly he called to me, and aimed his camera. There on the sand in the sunlight the Belgian army was changing its clothes. The faithful suits of blue, rained on and trench- worn, were being tossed into great heaps on the beach and brand-new yellow khaki, clothes and cap, was buckled on. It was a transformation. We had learned to know that army, and their uniform had grown familiar and pleasant to us. The dirt, ground in till it became part of the texture; the worn cloth, shapeless, but yet molded to the man by long association—all was an expression of the stocky little soldier inside. The new khaki hung slack. Caps were overlarge for Flemish heads. To us, watching the change, it was the loss of the last possession that connected them with their past; with homes and country gone, now the very clothing that had covered them through famous fights was shuffled off. It was as if the Belgian army had been swallowed up in the sea at our feet, like Pharaoh's phalanx, and up from the beach to the barracks scuffled an imitation English corps.

We went about miserable for a few days. But not they. They spattered their limp, ill- fitting garments with jest, and soon they had produced a poem in praise of the change. These are the verses which a Belgian soldier, clad in his fresh yellow, sang to us as we grouped around him on a sand dune:

Belgian soldiers in new khaki uniforms

EN KHAKI

- Depuis onze mois que nous sommes partis en guerre,

- A tous les militaires,

- On a décidé de plaire.

- Aussi depuis ce temps là, à l'intendance c'est dit,

- De nous mettr' tous en khaki.

- Maint'nant voilà l'beau temps qui vient d' paraître

- Aussi répétons tous le cœur en fête.

REFRAIN

- Regardez nos p'tits soldats,

- Ils ont l'air d'être un peu là,

- Habilles D'la tête jusqu'aux pieds

- En khaki, en khaki,

- Ils sont contents de servir,

- Mais non pas de mourir,

- Et cela c'est parce qu' on leur a mis,

- En quelque sorte, la t'nue khaki.

- Maintenant sur toutes les grand's routes vous pouvez voir

- Parcourant les trottoirs

- Du matin jusqu'au soir

- Les défenseurs Belges, portant tous la même tenue

- Depuis que l'ancienne a disparue, Aussi quand on voit l’9e dénier

- Ce n'est plus régiment des panachés.

Même Refrain

- Nous sommes tous heureux d'avoir le costume des Anglais

- Seul'ment ce qu'il fallait,

- Pour que ça soit complet.

- Et je suis certain si l'armée veut nous mettre à l'aise

- C'est d'nous donner la solde Anglaise.

- Le jour qu'nous aurions ça, ah! quell' affaire

- Nous n' serions plus jamais dans la misère.

REFRAIN

- Vous les verriez nos p'tits soldats,

- J'vous assure qu'ils seraient un peu là,

- Habilles, D'la tête jusqu'aux pieds,

- En khaki, en khaki,

- Ils seraient fiers de repartir,

- Pour le front avec plaisir,

- Si les quatre poches étaient bien garnés

- De billets bleus couleur khaki.

- 'Les Travailleurs de la Guerre'

- by Arthur Gleason

- from his book ‘Golden Lads’ 1916

The boy soldier is willing to make any day his last if it is a good day. It is not so with the middle-agèd man. He is puzzled by the war. What he has to struggle with more than bodily weakness is the malady of thought. Is the bloody business worth while?

I saw him first, my middle-aged man, one afternoon on the boards of an improvised stage in the sand-dunes of Belgium. On that last thin strip of the shattered kingdom English and French and Belgians were grimly massed. He was a Frenchman, and he was cheering up his comrades. With shining black hair and volatile face, he played many parts that day. He recited sprightly verses of Parisian life. He carried on amazing twenty-minute dialogues with himself, mimicking the voice of girl and woman, bully and dandy. His audience had come in stale from the everlasting spading and marching. They brightened visibly under his gaiety. If he cared to make that effort in the saddened place, they were ready to respond. When he dismissed them, the last flash of him was of a smiling, rollicking improvisator, bowing himself over to the applause till his black hair was level with our eyes.

And then next day as I sat in my ambulance, waiting orders, he trudged by in his blue, "the color of heaven" once, but musty now from nights under the rain. His head of hair, which the glossy black wig had covered, was gray-white. The sparkling, pantomimic face had dropped into wrinkles. He was patient and old and tired. Perhaps he, too, would have been glad of some one to cheer him up. He was just one more territorial—trench- digger and sentry and filler-in. He became for me the type of all those faithful, plodding soldiers whose first strength is spent. In him was gathered up all that fatigue and sadness of men for whom no glamour remains.

They went past me every day, hundreds of them, padding down the Nieuport road, their feet tired from service and their boots road-worn— crowds of men beyond numbering, as far as one could sec into the dry, volleying dust and beyond the dust; men coming toward me, a nation of them. They came at a long, uneven jog, a cluttered walk. Every figure was sprinkled and encircled by dust—dust on their gray temples, and on their wet, streaming faces, dust coming up in puffs from their shuffling feet, too tired to lift clear of the heavy roadbed. There was a hot, pitiless sun, and every man of them was shrouded in the long, heavy winter coat, as soggy as a horse blanket, and with thick leather gaiters, loose, flapping, swathing their legs as if with bandages. On the man's back was a pack, with the huge swell of the blanket rising up beyond the neck and generating heat-waves; a loaf of tough black bread fastened upon the knapsack or tied inside a faded red handkerchief; and a dingy, scarred tin Billy-can. At his shapeless, rolling waist his belt hung heavy with a bayonet in its casing. On the shoulder rested a dirt-caked spade, with a clanking of metal where the bayonet and the Billy-can struck the handle of the spade. Under a peaked cap showed the bearded face and the white of strained eyes gleaming through dust and sweat. The man was too tired to smile and talk. The weight of the pack, the weight of the clothes, the dust, the smiting sun—all weighted down the man, leaving every line in his body sagging and drooping with weariness.

These are the men that spade the trenches, drive the food-transports and ammunition- wagons, and carry through the detail duties of small honor that the army may prosper. When has it happened before that the older generation holds up the hands of the young? At the western front they stand fast that the youth may go forward. They fill in the shell-holes to make a straight path for less-tired feet. They drive up food to give good heart to boys.

War is easy for the young. The boy soldier is willing to make any day his last if it is a good day. It is not so with the middle-aged man. He is puzzled by the war. What he has to struggle with more than bodily weakness is the malady of thought. Is the bloody business worth while? Is there any far-off divine event which his death will hasten? The wines of France are good wines, and his home in fertile Normandy was pleasant.

As we stood in the street in the sun one hot afternoon, four men came carrying a wounded man. The stretcher was growing red under its burden. The man's face was greenish white, with a stubble of beard. The flesh of his body was as white as snow from loss of blood. It was torn at the chest and sides. They carried him to the dressing- station, and half an hour later lifted him into our car. We carried him in for two miles. Four flies fed on the red rim of his closed left eye. He lay silent, motionless. Only a slight flutter of the coverlet, made by his breathing, gave a sign of life. At the Red Cross post we stopped. The coverlet still slightly rose and fell. The doctor, brown-bearded, in white linen, stepped into the car, tapped the man's wrist, tested his pulse, put a hand over his heart. Then the doctor muttered, drew the coverlet over the greenish-white face, and ordered the marines to remove him. In the moment of arrival the wounded man had died.

In the courtyard next our post two men were carrying in long strips of wood. This wood was for coffins, and one of them would be his.

A funeral passes our car, one every day, sometimes two: a wooden cross in front, carried by a soldier; the white-robed chaplain chanting; the box of light wood, on a frame of black; the coffin draped in the tricolor, a squad of twenty soldiers following the dead. That is the funeral of the middle-aged man. There is no time wasted on him in the brisk business of war ; but his comrades bury him. One in particular faithful at funerals I had learned to know—M. Le Doze. War itself is so little the respecter of persons that this man had found himself of value in paying the last small honor to the obscure dead as they were carried from his Red Cross post to the burial-ground. One hopes that he will receive no hasty trench burial when his own time comes.

I cannot write of the middle-aged man of the Belgians because he has been killed. That first mixed army, which in thin line opposed its body to an immense machine, was crushed by weight and momentum. Little is left but a memory. But I shall not forget the veteran officer of the first army, near Lokeren, who kept his men under cover while he ran out into the middle of the road to see if the Uhlans were coming. The only Belgian army to-day is an army of boys. Recently we had a letter from André Simont, of the "Obusiers Lourdes, Belges," and he wrote:

If you promise me you will come back for next summer, I won't get pinked. If I ever do, it doesn't matter. I have had twenty years of very happy life.

If he were forty-five, he would say, as a French officer at Coxyde said to me:

"Four months, and I haven't heard from my wife and children. We had a pleasant home. I was well to do. I miss the good wines of my cellar. This beer is sour. We have done our best, we French, our utmost, and it isn't quite enough. We have made a supreme effort, but it hasn't cleared the enemy from our country. La guerre—c'est triste."

He, too, fights on, but that overflow of vitality does not visit him, as it comes to the youngsters of the first line. It is easy for the boys of Brittany to die, those sailors with a rifle, the stanch Fusiliers Marins, who, outnumbered, held fast at Melle and Dixmude, and for twelve months made Nieuport, the extreme end of the western battle-line, a great rock. It is easy, because there is a glory in the eyes of boys. But the older man lives with second thoughts, with a subdued philosophy, a love of security. He is married, with a child or two; his garden is warm in the afternoon sun. He turns wistfully to the young, who are so sure, to cheer him. With him it is bloodshed, the moaning of shell- fire, and harsh command.

One afternoon at Coxyde, in the camp of the middle-aged—the territorials—an open-air entertainment was given. Massed up the side of a sand-dune, row on row, were the bearded men, two thousand of them. There were flashes of youth, of course—marines in dark blue, with jaunty round hat with fluffy red centerpiece; Zouaves with dusky Algerian skin, yellow-sorrel jacket, and baggy harem trousers ; Belgians in fresh khaki uniform; and Red Cross British Quakers. But the mass of the men were middle-aged— territorials, with the light-blue long-coat, good for all weathers and the sharp night, and the peaked cap. Over the top of the dune where the soldiers sat an observation balloon was suspended in a cloudless blue sky, like a huge yellow caterpillar.

Beyond the pasteboard stage, high on a western dune, two sentries stood with their bayonets touched by sunlight. To the south rose a monument to the territorial dead. To the north an aeroplane flashed along the line, full speed, while gun after gun threw shrapnel at it.

As I looked on the people, suddenly I thought of the Sermon on the Mount, with the multitude spread about, tier on tier, hungry for more than bread. It was a scene of summer beauty, with the glory of the sky thrown in, and every now and then the music of the heart. Half the songs of the afternoon were gay, and half were sad with long enduring, and the memory of the dear ones distant and of the many dead. Not in lightness or ignorance were these men making war. When I saw the multitude and how they hungered, I wished that Bernhardt could come to them in the dunes and express in power what is only hinted at by humble voices. I thought how everywhere we wait for some supreme one to gather up the hope of the nations and the anguish of the individual, and make a music that will send us forward to the Rhine.

But a better thing than that took place. One of their own came and shaped their suffering into song. And together, he and they, they made a song that is close to the great experience of war. A Belgian, one of the boy soldiers, came forward to sing to the bearded men. And the song that he sang was "La valse des obus"—"The Dance of the Shells."

"Dear friends, I'm going to sing you some rhymes on the war at the Yser."

The men to whom he was singing had been holding the Yser for ten months.

"I want you to know that life in the trenches, night by night, isn't gay."

Two thousand men, unshaved and tousled, with pain in their joints from those trench nights, were listening.

"As soon as you get there, you must set to work. It does n't matter whether it's a black night or a full moon; without making a sound, close to the enemy, you must fill the sand- bags for the fortifications."

Every man on the hill had been doing just that thing for a year.

Then came his chorus :

"Every time we are in the trenches, Crack! There breaks the shell."

But his French has a verve that no literal translation will give. Let us take it as he sang it :

"Crack! Il tombe des obus," sang the slight young Belgian, leaning out toward the two thousand men of many colors, many nations; and soon the sky in the north was spotted with white clouds of shrapnel-smoke.

"There we are, all of us, crouching with bent back—Crack! Once more an obus. The shrapnel, which try to stop us at our job, drive us out; but the things that bore us still more—Crack!—are just those obus."

With each "Crack! Il tombe des obus," the big bass-drum boomed like the shell he sang of. His voice was as tense and metallic as a taut string, and he snapped out the lilting line in swift staccato as if he were flaying his audience with a whip. Man after man on the hillside took up the irresistible rhythm in an undertone, and "Cracked" with the singer. In front of me was being created a folk-song. The bitterness and glory of their life were being told to them, and they were hearing the singer gladly. Their leader was lifting the dreary trench night and death itself into a surmounting and joyous thing.

"When you've made your entrenchment, then you must go and guard it without preliminaries. All right; go ahead. But just as you're moving, you have to squat down for a day and a night —yes, for a full twenty-four hours—because things are hot. Somebody gives you half a drop of coffee. Thirst torments you. The powder-fumes choke you."

Here and there in the crowd, listening intently, men were stirring. The lad was speaking to the exact intimate detail of their experience. This was the life they knew. What would he make of it?

"Despite our sufferings, we cherish the hope some day of returning and finding our parents, our wives, and our little ones. Yes, that is my hope, my joyous hope. But to come to that day, so like a dream, we must be of good cheer. It is only by enduring patience, full of confidence, that we shall force back our oppressors. To chase away those cursed Prussians—Crack! We need the obus. My captain calling, 'Crack! More, still more of those obus!' Giving them the bayonet in the bowels, we shall chase them clean beyond the Rhine. And our victory will be won to the waltz of the obus."

It was a song out of the heart of an unconquerable boy. It climbed the hillock to the top. The response was the answer of men moved. His song told them why they fought on. There is a Belgium, not under an alien rule, which the shells have not shattered, and that dear kingdom is still uninvaded. The mother would rather lose her husband and her son than lose the France that made them. Their earthly presence is less precious than the spirit that passed into them out of France. That is why these weary men continue their fight. The issue will rest in something more than a matter of mathematics. It is the last stand of the human spirit.

What is this idea of country, so passionately held, that the women walk to the city gates with son and husband and send them out to die"? It is the aspect of nature shared in by folk of one blood, an arrangement of hill and pasture which grew dear from early years, sounds and echoes of sound that come from remembered places. It is the look of a land that is your land, the light that flickers in an English lane, the bells that used to ring in Bruges.

La Valse Des Obus

- Chers amis, je vais

- Vous chanter des couplets,

- Sur la guerre,

- A l'Yser.

- Pour vous faire savoir,

- Que la vie, tous les soirs,

- Aux tranchées, N'est pas gaie.

- A peine arrivé,

- Faut aller travailler.

- Qu'il fasse noir' ou qu'il y ait clair de lune,

- Et sans fair' du bruit,

- Nous allons près de l'ennemi,

- Remplir des sacs pour fair' des abris.

Refrain

- Chaqu' fois que nous sommes aux tranchées,

- Crack!

- Il tombe des obus.

- Nous sommes tous là, le dos courbée

- Crack!

- Encore un obus.

- Les shrapnels pour nous divetir,

- Au travail, nous font déguerpir.

- Mais, et qui nous ennuie le plus,

- Crack ! se sont les obus.

- L'abri terminé,

- Faut aller l'occuper,

- Sans façons.

- Allez-donc.

- Pas moyen d' se bouger

- Donc, on doit y rester

- Accroupi,

- Jour et nuit,

- Pendant la chaleur,

- Pour passer vingt-quatr' heures.

- On nous donn' une d'mi gourde de café.

- La soif nous tourmente,

- Et la poudre asphyxiante,

- Nous étouffe au dessus du marché.

- Nos femmes et nos enfants.

- Plein de joie,

- Oui ma foi,

- Mais pour arriver,

- A ce jour tant rêvé,

- Nous devons tous y mettre du cœur,

- C'est avec patience,

- Et plein de confiance,

- Que nous repouss'rons les oppresseurs.

Refrain

- Pour chasser ces maudits

- All'mands

- Crack !

- Il faut des obus.

- En plein dedans mon commandant,

- Crack!

- Encore des obus.

- Et la baionnett' dans les reins,

- Nous les chass'rons au delà du Rhin.

- La victoire des Alliés s'ra due

- A la valse des obus.

- Malgré nos souffrances,

- Nous gardons l'espérance

- D' voir le jour,

- De notr' retour

- De r'trouver nos parents,