- 'a Woman in Battle'

- at Belgium’s Last Stand

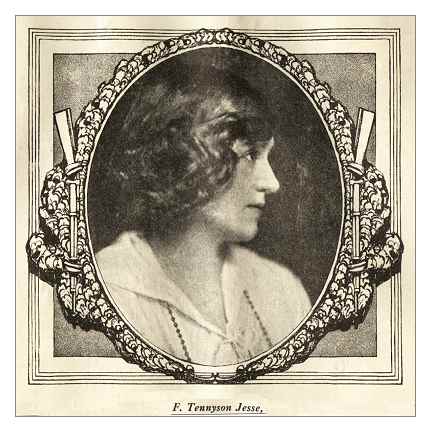

- by F. Tennyson Jesse

- from 'Collier's Magazine' November 14th 1914

- A British Lady Reporter

- F. Tennyson Jesse, grandniece of the poet Tennyson,

- is a London journalist scarcely twenty-five years old.

- She is one of the few correspondents to reach any firing line in Europe,

- and the only woman writer who has done so.

ANTWERP, September 25.

Yesterday I heard that there is fighting all along in the Alost and Termonde direction, and an American here (* E. Alexander Powell), with the necessary passes has promised to run me out through the lines in his car and to take me as near the battle as I am allowed to go. Both Germans and Belgians are very apt to look upon a woman as being of necessity a spy, and I have nearly been arrested by my own side many times already.

This running through the lines in a car which has the word for the day is one of the few things about the war which is at all like what one would have imagined. Mostly, the whole thing is extraordinarily unexpected, and it is hardly ever dramatic; but it always gives me a thrill, especially at night, when a light is flashed across the road, the command to halt rings out, and the car stops with a sudden grinding of brakes in the vague halo of brightness made by the sentry's lantern. Then to lean forward and say the "word" in a low voice, to hear the sentry's "Bien - continuez !" and to go whirling on, when less favored folk are held up perhaps for half an hour over papers and then not allowed to pass - all this has the real cloak-and-dagger dramatic touch about it. My landlady has just brought up my petit dejeuner, and is aghast to hear I am going to try and get into the battle. She is rather a beautiful creature in the low-browed, solid way of the true Flamande. Her fair hair is cut in a straight fringe, from beneath which her eyes - those small, narrow eyes which can be so sweet - beam out at one and her mouth is big and curved and a little blurred at the edges. She is a dressmaker and lets lodgings, and her husband, a quiet, gentle little bourgeois, is a designer of canoes and pleasure craft; of course without work now. They are very plucky though she is appallingly nervous and high-strung, and very wrapped up in the first baby, a girl, when I am allowed to help bathe. No time for that this morning, as I must be off.

They are a very typical little bourgeois family of the best type, and it is interesting to watch them through all this. I came here instead of to a hotel because journalists are supposed not to be allowed in Antwerp, and at a hotel one has to fill in a dossier on arrival and soon afterward an official arrives and tells you what time your train leaves.

War and the Individual

OSTEND, September 27.

I got into my battle all right, but entirely by use of the personal equation which is a thing I deplore. I came out to this war with a theory that one of the chief benefits of it was that it eliminated the personal equation - that individual life became less important, and that relationships between individuals became less important still. I am beginning to think I was mistaken and that war intensifies the personal element. As far as the correspondents go, luck which after all, is an entirely individual matter, is the chief factor. The difficulties in the way of even the men correspondents are extraordinary. The Germans have orders to shoot any they may catch as spies, the Belgians object to them for fear the enemy might force information out of them when caught, and the English authorities are consistently uncivil and ungracious. For a girl the difficulties are multiplied, as all sides consider one a spy and when it comes to getting out with other journalists, the nice men do not want one because of the danger to oneself, and the others because it so increases the danger to them. Also it is quite impossible to do anything in this war without an automobile and they are all commandeered by the government, and it is impossible to hire one unless one can coax a permit out of the military authorities. Women are supposed not to be allowed in motor cars in Belgium and the chief of staff himself could not take his own wife in one so all things considered, I have had extraordinary luck. And luck, much as one lights against the truth of this, is largely a matter of the personal equation. It was owing to the sympathy and courtesy of certain Belgian officers that. against the general's orders, I went into the fight with them.

Not Entirely the Finish

It was this way: We came to the village where the general had his headquarters, and where regiments of guides in their cherry color and green and of lancers in their blue and gold were awaiting the order to advance. Here apparently, was the finish as far as I was concerned, for on reaching the far end of the village a very polite colonel regretted to inform me he had orders not to let me pass. So I had to stay behind while the rest of the party went on.

It was an exquisite day on which to be alive with a clear, hard, blue sky that paled to whiteness toward the flat horizon; on either side of the interminable roadway the poplars stood ranked, gray trunk after gray trunk, and the sunlight flickering through their foliage made a pattern of dappled shadow over the men and horses resting beneath. The village itself was bare and mean, nothing but a fringe of half a dozen one-story cottages, but it was superbly decorated by the glint of lances, the gloss of the horses' flanks, the gold and cherry and green and blue of the uniforms. The men were mostly fine looking, with light eyes and keen-edged faces under the black fur of their busbies. They stood about in little groups and chatted to each other and to me, and I found them most courteous and considerate. After taking some photographs and drinking a glass of milk. I managed to slip out of the village and on up the road to where the crack-crack of rifle tiring told of the fight. This was not a difficult feat, as I was told that, though I could not be given permission to pass yet, I was so small that if I just strolled along on the other side of the road they, the officers, would simply not be able to see me.

Bullets or Dreams ?

So I walked about a couple of kilometers up into the fight, but before I reached it I met a motor-cycle scout tearing down, and a few minutes later, with a clatter of hoofs and a jingling of accouterments, all four regiments rode past, saluting as they went. and followed by the artillery that thundered with gray iron wheels over the cobbles. So I came to the village of Erpe, with no further incident than that a couple of officers wheeled their horses to tell me the bullets were flying further up the road, but they wished me luck, as I did them, and allowed me. to continue. At Erpe I nearly got into trouble, since I had very idiotically forgotten to take my papers out of the car. but while the sentries were still discussing among themselves whether they should ask me for any, I walked on, and in their amazement at seeing me there at all they did nothing.

At the. end of the village I came on the others, on the car and on the fight. The Belgians had just driven the enemy back, and on a field by the road's edge lay two Germans, with their faces shot away - what had been men now a mere huddle of gray on the brown earth by the newly turned trench. Apart from the pitifulness of that sight the whole affair was extraordinarily unlike what one reads in books. The chief note was the. scattered air of the thing, the casual grouping of men, here and there some one riding off across the fields to reconnoiter, the peasants coming out of their cottages to see the dead soldiers, though the bullets were clipping the leaves off the branches just above our heads as we stood there. The peasants were soon bustled back again - indeed, the whole affair suddenly took on a hustling, confused quality - the Americans and one or two officers coming up and saying we were all in the direct line of fire, the fact that the sun had gone in and a grayness blurred everything, the dropping of the shot leaves, and twigs about one, or the chipping of a stone into sudden whiteness near one's feet - all these things gave an odd feeling of being in a dream.

The Orchestra in the Field

Odd, too, was the queer little plaintive noise made by the bullets, rather like a sobbing whine. They went sighing beside one, and the sound of their going was as clear as though some one had given a little moan or a bee had gone twanging past, and yet one could not see the thing,, themselves. It was only as though the air were stinging with invisible insects. This probably accounts for the unalarming nature of rifle tire as compared with shells or shrapnel. You simply, in the former case, do not feel under fire at all. I was put into a doorway, others took cover behind trees or in the ditch; then the order to retreat was given and I was hustled into the car and told to lie as flat as possible.

After a while we all retreated once more to the stretch of road the other side of Erpe, and there, over to the right, as one looked back toward the village, the artillery got into action, keeping it up steadily, so that it soon became monotonous, like an orchestra at dinner.

To the left, from the village of Lede, whose roofs showed red beside some dark patches of woods, all the peasants streamed toward us over the bright fields. One is used nowadays in Belgium to this perpetual procession, always going past in profile, bundle on back, children on arm, and helpless old folk in wheelbarrows, an endless frieze of bowed figures, dark against the clear autumn horizon. Yet every time the misery and futility and unnecessary cruelty of it all strike at the mind more deeply.

Cherry and Gold and Green Lancers

Presently a Belgian officer was wounded in the thigh, and his hurt attended to there on the road by the Red Cross, and soon after a couple of the new steel-domed mitrailleuses dashed past along the road toward Alost, but apart from that it was dull work, until at last there occurred one of the prettiest sights possible. and one rare in modern warfare a cavalry charge across the fields to where the enemy were thought to be concealed beyond the woods. The lancers had been reconnoitering there, and every now and then the tips of their lances would catch the evening sun and gleam like thin flames against the dark foliage; now the guides jumped their horses over the ditch and formed up in the field amid the light and vivid green of the sugar-beet crop which stretched to the Woods.

Then, head by head, fine legs flashing, the horses swept past and away; and cherry and gold and green went twinkling over the bright, level acres, and one wished good luck to go with them.

This was really exceptional good fortune, as it cannot be too much emphasized that this is a war, not so much of men, as of machines. It is really a war of four things - the air fleets, big guns, automobiles, and submarines.

Cavalry and infantry are of secondary importance. This lovely flashing action of the cavalry was the most vivid thing, as the poor dead Germans and the homeless peasants were the most pitiful, that I saw in all that crowded yesterday.

At ten I got into Bruges and dined, and then came on here, where I find nothing is doing, though one had heard the usual fairy tales about Russians and British having landed.

Right Under the Zeppelin

GHENT, September 28.

The car in which I was promised a lift yesterday broke down, and after a fruitless day at Ostend I had the luck to be given a place in a small open car, the last in the town, belonging to the military commander, which was coming here. Burst a tire on the way, but the moonlight was so wonderful that I didn't mind, although it was intensely cold. Finally got into Ghent at midnight, and there, as we were crossing a bridge, we saw a Zeppelin right above us, so high she was soundless, making her way westward.

Gray and ghostly, blotting successive stars, she slipped like a mouse along, the sky, and the menace of her somehow only added to the wonder and the, beauty of her, so tiny at that height and yet so deadly. I found I was shaking all over with a mad excitement - the first time in all the weeks I have been at this wretched war when I got a pure thrill of emotion.

Nothing doing in Ghent all to-day, except the usual stream of refugees and wounded.

The Desperate Metropolis

ANTWERP, September 29.

Arrived back here to-day in the car belonging to Mr. Van Hee. The American Vice Consul for Ghent, whose decisive action when the two Germans were shot in the town has already been chronicled by Mr. Powell of the "World," and made him famous. And I may mention here that every bit of help rendered one in this war, where all men's hands are against one, has been rendered by Americans. I for one, shall never again be able to look on the Stars and Stripes without a feeling of gratitude for its protection.

No particular activities along the road. A lovely, clear, wind-blown day, with showers and sunlight. When we began to come to the outposts the sentries were much more fussy than ever before. and we could not get through by just giving the word for the day, but had to keep on showing our papers. The Belgians are very busy strengthening the lines of defense. There are, of course, the two zones of barbed-wire entanglements which girdle Antwerp, and into which all the city's electric current can be turned so as to make them as fatal as the death chair at Sing Sing; in the sun they glistened like gigantic cobwebs.

The Guns Begin

Besides these, the position is being further strengthened by the planting, over large cleared spaces, of sharp stakes. which would prevent a cavalry charge - the air is full for a long way of the good smell of freshly hewn timber. The earth is still light in color over the masked batteries, so that it looks as though Titanic children had been making sand castles. Every now and then in an innocent-looking field you see a stake painted vermilion, which indicates a buried mine. Peasants will probably go on turning up mines and unexploded shells and getting killed after the war is over.

The Scheldt was looking, exquisite, broad and blue, and the gray towers of Antwerp rose into the pale, misty sunlight on the far side, looking the most peaceful things on earth. The tide was low, and the new pontoon bridge, made of planks laid across iron girders, which are supported by canal boat, was a perfect switchback, sagging right down in the middle.

Antwerp at present looks like a medieval city in time of tournament, for all the houses have huge Belgian flags draped like arras from the windows. The festive air this gives seems all the more incongruous now I have heard the news - which, of course. according to the Belgian system of hoodwinking the public, Is not being given out in the papers. The bombardment has begun, the Germans having apparently two of their enormous guns at a base beyond the railway, and the big forts of Lierre and Waelhem are destroyed already.

Facts Without the Sugar Coat

Just met Mr. Patterson, the owner of the Chicago "Tribune," and Mr. Powell on their way back from an expedition to the forts. They left Mr. Thompson, the photographer. to spend the night there, and themselves saw a shell explode over a cluster of houses from which a little procession of peasants presently came forth. One man was wheeling a barrow with his small stock of worldly goods on it. and the dead body of his little son lay sprawled over the top, while Sitting beside it was a girl of three with her face covered with blood. They say the sights are too ghastly, and that the situation is so grave everyone should get out of Antwerp who is not bound to remain.

I refuse to go of course, but I felt I ought to tell the truth to madame and her husband. The Belgian papers are not publishing anything about the real danger, but merely announce that the Germans have been repulsed with heavy losses. Every government concerned seems to be going in for this system of doctoring the truth.

If it is to deceive the Germans, it is quite futile, since their ways of getting knowledge are wonderful, and it is impossible to make the slightest movement of troops without their knowing it. If it is to encourage volunteering, it is a still greater mistake, as every time bad news is allowed to come out there is a greater rush to join the colors.

Tonight before dinner, I told madame the true state of affairs, and tried to impress upon her that she must get a passport and have everything ready for flight. She was very upset, having been living like the rest of the town, in a state of false security.

Later the officer who lodges on the second floor came in from the fort with the same news. and then monsieur came in, knowing nothing and had to be told. We had a curious dinner - he, she, and I - in the primly furnished dining-room with its walnut "suite" on the sideboard, an impossible dog in white metal, which is, really a money box, in which every spare coin is put for the baby.

The Big Tragedy in Little

Poor little madame's eyes kept brimming with tears; she held the baby on her arm all the time and kept on kissing it; monsieur cut up her dinner for her and she ate it mechanically with her spare hand. Somehow nothing in the whole war has brought the cruelty of it more sharply to mind than this dinner with these two little Belgian tradespeople. I have seen terrible things - ruined towns, women whose husbands and sons had been taken away they knew not where, refugees who lay almost too exhausted to keep on living, but they were all piteous sufferers. not separate entities. to me. These people I know. I have lived in their house with them, and, such is the inadequacy of imagination and the force of the personal equation, it needed the bewilderment and pluck and grief of these ruined but still uninjured bourgeoisie to make me understand.

All their home, which they have got together with such pride, from the hideous pictures in the spotless little salon to the crowning glory of a bathroom with a gas meter - all this has to be abandoned : their money is down to the last few francs; all madame's well-to-do clients have fled, owing her for the gowns, she has made for them this year; monsieur has nowhere to turn for ready money. They are a good, simple couple who have, I am sure, never hurt anyone, and who had always thought - if they thought at all - that they would go on working and getting more prosperous, that they would eventually buy the house and add more still to its, glories. And that the little one would be brought up like a lady. And now all their world has tumbled about their cars metaphorically, and it will not be long before it proceeds to do so literally. Monsieur talked mostly to me all dinner about England and work, but he never took his quiet, steady eyes off her and the baby, who was chuckling and had one tiny fist caught in its mother's hair.

"But Where Are the English?"

SEPTEMBER 30.

The forts are in ruins, but instead of retreating to the next line the Belgians are going to defend the river. The German infantry are advancing under cover of their field guns, and already the shells are falling inside the defenses. The photographer came back to-day with even his nerve a little shaken - a shell burst into the fort in file night and killed nine men in the room he was in. including a waiter from the St. Regis at his side, who had his head blown off. The photographer tore down the road screaming, but he's going back tonight.

The whole countryside to-day is simply plastered with dead. Many wounded women are being brought along on stretchers with their poor mutilated faces covered. Shell wounds seem often in the head and face. I am writing this in my room at night with the boom of the heavy firing sounding all the time. Antwerp is, of course, velvet dark, but I have just stolen out to the corner of the road and seen where the sky is red and glowing with the burning Malines, like a fierce aurora borealis. Everyone is saying: "But where are the English ?"

The feeling over here is a little bitter, and one cannot blame them. They say that Belgium has been left to be strangled, which is exactly what is happening. and yet I suppose we sent all the men we had to France. But they are still much more enthusiastic about us than about the French. They declare, I dare say with reason, that at the beginning the French had a splendid chance to pour into Belgium and help, but that the glamour of Alsace and Lorraine was too much for them, and so they concentrated there instead.

Disease Also

OCTOBER 1

The water supply ceased to-day, since the bombardment at Waelhem destroyed the reservoir.

If something isn't done we shall probably get a pretty bad outbreak of disease here as there is elsewhere in Belgium now. There is smallpox pretty nearly everywhere, and typhoid is beginning in some places. Poor, poor Belgium ! - it is this country, and not France, which, win or lose, is the tragedy of the war.

Waterless and in the Dark, Yet Enduring

OCTOBER 2.

Here is still no water - they talk of filtering the Scheldt water for the town - let us hope they filter it well, as everything drains into it. The Belgian officer who lives in this house says the light in the sky came from the burning of a lot of straw which the Belgians had soaked in petroleum and lit, so as to make the Germans think the forts were on fire, but I don't get this confirmed from more official quarters. Certainly the bombardment has slackened somewhat.

If the Germans should take Antwerp while the King is there, it's all over with Belgium, but he and the Government are going to move to Ghent or Ostend and leave only a small force here. Great movement of troops through the town all day.

This afternoon I was lying down in my room when I heard a terrific banging. and. looking out, I saw shrapnel bursting down through the. air. Running into the street, I was hustled under cover by gendarmes, and found we were firing at a Taube which was flying just overhead. It got away. but didn't drop anything worse than all impertinent proclamation.

Went crawling along the house fronts in the dark till evening to buy cakes for supper at a patisserie in the Chaussée de Malines, and saw infantry and artillery going through. There are 5 000 refugees clamoring at one of the city gates, but no more are allowed in, instead they are being diverted by way of Ghent, because of a shortage of provisions. Butter and vegetables are scarce here now.

Time Limit

OCTOBER 3.

My landlady has just come into the room in a great state of nerves and misery - the officer has just come back from the lines and says there is only till midday to get out and that the route to Ostend is the only out left open. I shall stay. of course, so I shall have to find a hotel. It appears the Germans have practically encircled the town with the exception of that one route, and that some of the forts are actually in their possession. The King is going to Ostend. I am trying to make madame eat something. It's no use trying to be a refugee oil an empty tummy. Nearly all the baby's linen is in progress of being washed, Which is unfortunate. The officer is coming back again to tell madame and her husband all about trains, etc.

What Monsieur Said

12.00.

THE officer just in - he says no one can go by rail, as it is being used for the military, and that the Harwich boat is the only way. But it's a sure thing that all Antwerp can't get in that boat. Madame is crying so, poor woman ! Her husband is splendid - he is so sad, and yet he cheers her up and says: "We are young and strong, we have our hands, we can gain our living in England."

Poor Madame!

1.30.It now appears that the Ostend route is closed to civilians and that the Holland route is open, though the train does not go the whole distance. They have taken all the wounded out of the hospitals here and the streets are full of them, being carried along - men without a leg or an arm, or with their noses or even their lips shot away. It is horrible. Madame's brother-in-law just came in and says the Harwich boat is for British subjects only. No one seems to know from moment to moment what to do next.

Madame is quite incapable of getting a real lunch, so we all picnicked on the remains of my cakes. We are now busy sorting out monsieur's clothes to give the soldiers who are left, in case they have to scurry into civilian garments. For the officer upstairs madame has unearthed a suit left behind by a German who used to lodge here - rather a nice bit of poetic justice. The servant girl, who quite lost her head and shrieked with terror this morning because the Germans were coming, is now surprised because she isn't allowed to waste her time cleaning the house as usual.

Buried Treasure

5.30.

I spent the afternoon helping madame, who is a dressmaker, put all her yards of lace and embroidery, etc. into a tin box. We peppered it well against moths and buried it in a hole dug by monsieur in a corner of the workroom, which is a sort. of studio in the garden. It was odd, working there in the. waning afternoon light, the black cotton-covered bust, looming like grotesque ghosts from the corners. "This is the burial of a German victim." said monsieur, as he stamped the earth down over the tin box, and even madame smiled - through her tears. All the time she folds things she keeps on saying: "But, you know, I can't believe I'm going. I can't believe it."

The officer has got a motor car and is sending them with his wife via Holland. The whole of the British colony is down scrambling for places in what may be the last Harwich boat - and grumbling at the accommodation! So British!

Here Come the English

9.30.

I just got into a little hotel on the Place Verte. Winston Churchill has arrived in Antwerp and is dining with the King. There is a rumor that he says if we can hold out till Monday, 25.000 British will arrive. Meanwhile 2,000 infantry are now arriving - though unless artillery comes to back them up they will simply be sacrificed. They are chiefly to encourage the Belgians to keep on, and certainly their arrival is having a wonderful effect, and the volatile Anversois now consider they are saved. The King is remaining on, anyway, for a while.

*see The Naval Brigade in Antwerp

What the Germans Promised

OCTOBER 4.

Driblets of British troops keep arriving in cars amid the cheers of the people, a remarkable demonstration for the reserved Anversois. Thousands may have left, but Antwerp has probably never looked so gay or so crowded, with its people all in the streets and flags and cars everywhere. The chief danger in Belgium is that of being run over, and the chauffeurs will never bear to drive normally again. The Germans have taken the first line of forts, and ate trying to cross the river. The most interesting event to-day - and not without its humor - is that the German general has sent a telegram saying that if a plan of Antwerp, with the antiquities, hospitals, etc. marked on it in red, is sent him, he will endeavor to spare those places. There'll be a rush for the red spots if the Germans start shelling! But of course, they're bound to make some mistakes getting their range. The first map got up by the civil authorities here was practically one blur of red, and General Deguise remarked he didn't think it a good time to try and joke with the Germans.

Thank goodness, warned by the fate of Rheims, the Belgians. have taken down the gun which they had actually mounted on the cathedral against Zeppelins. The Germans do, it is true, behave with terrible barbarity, but some of their allegations, such as being fired on by civilians, are perfectly true, and they would undoubtedly be justified in shelling the cathedral if a gun were mounted on it.

The Belgian Government foists doctored news on the public-none of the townspeople know the Germans have captured the forts. If the Belgians merely manage to hold their own, it is put through in the papers as a victory, while all this taking and retaking of ruined towns is made the most of.

This afternoon I was at my window when a storm was coming up - the sky was a dark slate color, and against it the, cathedral, in full sun, showed a pale greenish gold Instead of its usual gray. The glory ran all around the tops of the houses for two sides of the place, and against it the naked twigs of the trees, with the empty nests clinging like big burrs, stood out black and sharp. The glow still held on the roofs when file storm broke, though the whole of the quickly deserted place was brown and glossy with rain.

Flashes of Beauty

OCTOBER 5.

The British soldiers lodging in this hotel were all routed out to go to the front in the middle of the night - such a calling for boots and coats and whirring of cars. Nothing decisive has happened all day. To-night is foggy, a good night for Zeppelins. As I crossed the place I saw, nebulous through the damp mist, the searchlight sweeping the sky. It looked extraordinarily beautiful is it described a rhythmical are over the deep blue, and the fact that it was being used purely for the defensive, and not for attack, gave it a benignity most beautiful sights do not possess just now.

Apathy

OCT0BER 6.

Firing very heavy all night. The news to-day is bad: the only cheerful thing - and that has its grim side - is that Mr. Gibson, the American Consul General from Brussels, has arrived to take the plan of Antwerp to the German general. The Germans have crossed the river Nethe, and Antwerp, like all the Belgian towns, is alternately seared and apathetic. This evening the firing is distinctly nearer. The war is not so much alarming as intensely depressing - at first the ghastly sights are shocking almost to the point of being stimulating, but after weeks of it a deadly depression eats into one I think everyone here feels he would like to get away into some warm, sunny, peaceful place, and never bear of a war again all his life long.

Nearer and Nearer

The bombardment is very loud now. The only reinforcements which have arrived to-day are twenty-five men of the Colonial Light Horse, who have been sent up from Ostend - why. they know not - without even their rifles! The infantry has been practically sacrificed. Three thousand British casualties since Saturday, though, of course, we will not be allowed to say so in the papers. I hear that some of the men In the trenches to-day, though fighting splendidly, felt a little bitterly that they were being thrown away without a chance. Apparently the Germans succeeded in crossing the Nethe in two places. Their artillery is wonderful. The whole aspect of affairs has changed. The coming of a couple of thousand on Saturday did what it was meant to do - heartened up the Belgians, whose morale was slackening, and the general opinion even among those who know was that Antwerp was safe. Now all is changed, and the last boat leaves to-night. It is impossible to get out via Ghent, as the road and railway are blocked.

Most of the Anversois are still as calm as though nothing were happening - probably because we are all so used to cannon by now. The last boat leaves to-night. It is the Harwich boat, though it now goes to Tilbury. The rule about British subjects only is done with, and the refugees are crowding on board. I also have to leave, very unwillingly, but the only foreigners remaining are a few Americans attached to the consulate, and I should imperil their chances of escape so if they were hampered with me, and they would never agree to my trying my own luck alone.

Exodus

OCTOBER 7.

I’ve left. I nearly walked on shore late. last night after I'd been put aboard, and it took all my knowledge of the selfishness of the. action to restrain me. It does seem hard to have to leave now, simply because of file personal equation.

All was very dark at the quay, only the pale beam from the searchlight swept the sky over and over; on board the refugees mostly huddled uncomplainingly down in the hold, In the foc'sile, along the narrow decks, on the companionway, everywhere. Old and young, men, women, and children, they sat huddled together in the biting cold all night, and in the alleyways the odor of peasant refugee, which once smelled is never forgotten, was strong.

The last we heard of Antwerp was that steady roar that punctuated the stillness, and we drew away, wondering whether what was expected would happen at last - the bombardment of the town itself. All day to-day, throbbing over a steady sea, without incident save being overhauled by a destroyer we have been without news. This boat is tiny, only some 500 tons, and we are nearly seven hundred people aboard. The bread, for some obscure reason, Is mildewed and we have to cut the green bits out. We shan't reach Tilbury till late, I fear, for besides dodging German mines we have to go round two sides of a triangle to escape the British mine field, and this ship is only good for fourteen knots.

The Stern Censor

OCTOBER 8.

We got in at ten, and were told no one was to be allowed to land that night. However, I made friends with the pilot and was dropped through the coal-port door into his boat, in preference to getting down the swaying rope ladder from the main deck. I got up to London at midnight and went to a newspaper office, where I found them all very interested to hear the truth about Antwerp, but said frankly that there was not the smallest chance of most of It passing the censor, which turned out to be the case. As to whether the town of Antwerp Is being bombarded, uncertainty still reigns. One hopes that even It the town Is shelled the result may not be as awful as It has been in other places. But, apart from that, Antwerp is in a bad plight since, owing to the destruction of Waelhem reservoir, there Is no pure water and also there is a shortage of surgeons. When I left I beard that the Stars and Stripes was to be flown over the field hospital, since the head surgeon is an American. Humanity owes much solace in this war to the fact that America is a neutral, power.

One Ally to Another

I hear from a good source that at last reinforcements are being sent to Antwerp via Dunkirk.

The only chance is to capture the German guns or put them out of action, and drive the Germans themselves over the river again. The town is being severely shelled, and at. the moment of writing the issue is uncertain, though by the time this appears in print in an uncensored land the fate of Antwerp will have been decided one way or another. At least this chronicle has the merit of having been written not only day by day, but almost hour by hour, and that it is free of the exaggerations and glamour that is apt to creep into the backward view.

If Antwerp falls, the tragedy of Belgium is complete - and it is an undeserved tragedy. I have mixed with her people for many long weeks now, and I can honestly say that, though often foolish, the Belgians are extraordinarily free from vice. It has been rather a habit of mind, since the revelations of the Congo, to call the Belgians a cruel race. Nothing could be further from the truth. There is always a bad element in the people of any nation which can be made use of, and this was the case in the Congo. But, though I have, it is true, seen a Belgian Red Cross man commit the idiocy of having a pistol strapped to his belt, I have proved them most humane, and that in face of great provocation, in their treatment of the German wounded. Just as I believe the worst accounts of German atrocities to be often much exaggerated, so I am convinced that there have been no atrocities at all on the part of the Belgians. They are often foolish; brave enough but panicky at the wrong moments - as when the Germans were within a few kilometers of Ghent and several thousand Gardes Civiques threw their uniforms in the canal and were running about in pink and blue underclothing. Also it is certain that if the enemy had made a perfectly peaceable entry into the town, there would have been some hotheaded Belgian, with false ideas of courage, who would have shot at them. The Belgian organization leaves much to be desired, and when the enemy is almost at the gate you will see the soldiers on leave quite drunk by the afternoon. But the Belgian soldier is one of the bravest creatures and one of the gayest on earth. He sticks a rose in his rifle and goes off to certain death with a song on his lips and a prayer in his soul and a devotion to his country in his heart which has never been surpassed.

*see also 'Collier's'