- from

- 'TP’s Journal'

- of

- Great Deeds of the Great War

- October 24, 1914

The Fall of Antwerp

THE TRAGIC LEGION

The Flight from Antwerp

The thin grey of the dawn steals through the lowering gloom of the night, and invades the face of nature as the first pallid gleam of returning consciousness invades the face of a sick woman. It is a wan and terrible light, utterly feeble, utterly without hope. The flat surface of the black dock water, rippleless, polished, inscrutably still, throws back the ashen grey of the new day with a chilly glow, and in this growing misery of light the tragedy of Antwerp masses and looms.

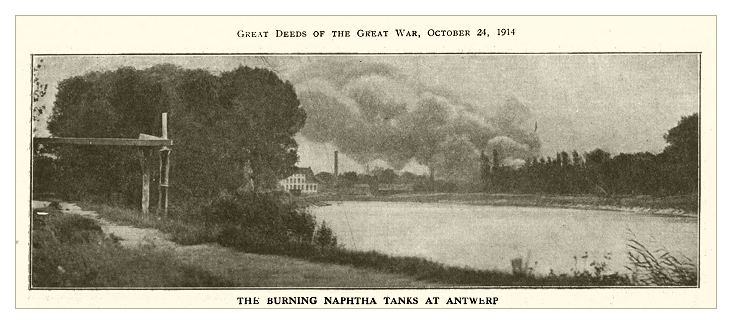

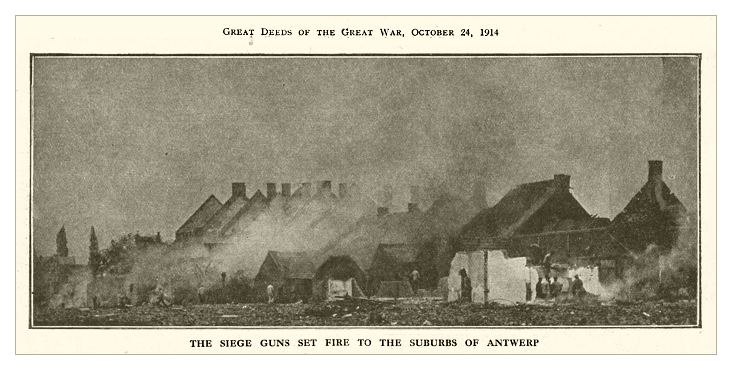

Along the dock-side, and as passive as though hewn in one piece with it, a crowd of Antwerp's citizens are standing. They stand awfully dumb, quiet, dreadfully immobile; they are massed and sculptured in lines of catastrophe that would be the despair of Rodin. Behind them, against the heavy dawn, Antwerp burns. The pulse of a hundred fires are flickering on the sky, and above the flames the thick smoke rolls. Down near the river the naphtha tanks are flaring, and the thick fume of the burning makes a pall of the deepest black over the doomed city. Behind, the canopy of smoke is laced with plunging shells. The earth shakes at their huge explosions; houses are being shattered and palaces battered to rubble. The great town appears merely an empty shell of smoke-blackened ruin, with no life save the fires of destruction burning sullenly within its heart. The town is destroyed; but it is not that which matters. That is not the Tragedy of Antwerp. Not in crumpled ruin or in shattered Gothic does the tragedy of these brave, pitiful people lie. It lies here, massed along the dock-side, and it is written in wailing on all the roads leading to the coast and to the hospitable Holland border. It is the tragedy of a people ruined, of a people destitute, starving, homeless, and torn from all ties that are dearest and most tender, by the ruthless hand of war.

Ourselves

Here on the quayside the people have come down to get away from the terror of the town by boat. They do not care what boat. All they crave is to get away. There are no steamers, but only a few tugboats to take and forty thousand men, women, children, and are waiting there. It is Patience in its most hopeful guise. It is impossible for more than a few to leave this way.

There are all manner of people in the crowd-the people you and I might meet in trams, and sit down with in restaurants, and welcome about our intimate firesides. They are not of a particular species of humanity, peculiarly fitted by Nature to withstand the horrors of siege and the quaking terrors of flight. They are the same people as our mothers and fathers and sisters; and the little babies in their arms are as the little babies that move so softly in our arms. They have been shelled by giant shells beyond the endurance point, they have learned that their Stout lines of forts have been shattered by the mighty power of the same shells, and they know now that, in spite of the indomitable resistance of the plucky Belgian army and the force of British blue- jackets and Marines assisting it, their town is doomed to fall into German hands. They know the German is upon them. They remember Louvain and Malines, and they are flying.

Woe to the Laggards

It is necessary to fly. Those who tried to remain were forced out of the town by their unendurable tragedies. In one case a man, weeping - and what wonder - told of his departure. The house next his home had been hit and burned. His wife prayed him to take the children and flee, leaving her, for she was an invalid. Death had seemed to await them if they stayed, and death, too, if they went. At last he found some neighbours willing to take the children, and to them he gave all the money he could spare. Alone with his wife and their youngest child he stayed in his home fighting the flames of the house next door. At last the flames conquered him. Hi5 own house began to burn and to crackle. There was nothing for it but flight. On a hand-cart he had laid a mattress and blankets, and on that he put his wife and her child. His right hand had been severely burned, but he never felt the pain. With his sorry freight he started on the road. It was twenty-four hours later before he met succour. His wife was weakening in strength. The child had had no milk for sixteen hours. The other children had disappeared in the tremendous throng-it may be months before they can be traced.

The Shells Have No Mercy

Not only on the quayside, but everywhere, the town is full of flying people. They are pressing outward along the roads in strange, dishevelled, and woebegone crowds; they are escaping by railway whenever such escape is possible, and they are waiting patiently at the head of the pontoon bridge that spans the Scheldt. At the pontoon bridge they are patient with an infinite patience. The bridge is used for military purposes, and only at intervals can the crowd pass over it. So they wait, a harrowing collection of men and women of all ages and of all conditions and grades in the social scale.

After interminable pauses their patience is rewarded, and for a few minutes they can move onward over the bridge, men and horses and wagons crawling forward at a snail pace. Then all too soon the military come, and the way is stopped. Patiently they wait again. There is no murmuring. A path is readily made for the soldiers and the Marines; sympathy is readily given to the wounded who trail past. And yet over them all the while the deadly shells are screaming, so close that some fall hissing into the river, so close that some behind them kill fellow-fugitives hurrying to join the waiting throng. The shells have no mercy. One smashed into a house and blew an entire storey to bits. There were only two women in the place; they were then packing to escape, and the shell slew both. At another spot a journalist, hurrying out of the way of the shells, came upon a woman in an exposed street. She seemed distraught, and he tried to get her to safety; but she drew him back along the street to where a man lay dead. The man was her husband, and a shell had struck him dead at her side as they were flying from the town to safety. Soon the shells have cleared the town. Only the pathetic dogs sit waiting on the doorsteps in desolate streets for masters who will not return.

Twenty Miles of Sorrow

Presently the pontoon bridge was unavailable, for the authorities had been forced to destroy it. The patient crowd bad to seek other avenues of escape. The railways were finished. The last train had already gone, crowded with people in every compartment, in every corridor, and even upon the coal in the tenders and the roofs of the carriages. The fugitives had left only the roads.

Out towards Ostend and towards Holland the mass of fugitives went streaming, converting, as a writer in the Times states, the long white roads into dark ribands, twenty miles long, of animals and humanity. Moving at a foot's pace went every conceivable kind of vehicle: great timber wagons, heaped with household goods, topped with mattresses and bedding, drawn by one or two slow-moving, stout Flemish horses, many of the wagons having piled upon the bedding as many as thirty people of all ages; carts of all kinds; everything loaded as it had never been loaded before, and all alike creeping along in one solid unending mass. Between and around and filling all the gaps among these vehicles went the foot passengers, each also loaded with bundles and burdens of every kind, clothes and household goods, string bags filled with great round loaves of bread and other provisions for the road, children's toys, and whatever possessions were most prized. Men and women, young and old, hale and infirm, lame men limping, blind led by little children, countless women with babies in their arms, many children carrying others not much smaller than themselves; frail and delicate girls staggering under burdens that a strong man might shrink from carrying a mile; well-dressed women with dressing bags in one hand and a pet dog led with the other; aged men bending double over their crotched sticks.

The Pathos of Pets and Playthings

Mixed up with the vehicles and the people were cattle - black and white Flemish cows, singly or in bunches of three or four, tied abreast with ropes, lounging with swinging heads amid the throng. Now and again one saw goats. Innumerable dogs ran in and out of the crowd, trying in bewilderment to keep in touch with their masters. Men, women, and children carried cages with parrots, canaries, and other birds one woman carried a green parrot that clung desperately to her wrist through all that desperate march; and, peeping out of bundles and string bags - generally carried by the elder members of the families - were Teddy bears, golliwogs, and children's rocking-horses. It was impossible not to be touched by the tenderness which made these wretched folk, already overburdened, struggle to take with them their pets and their children's playthings.

Pitiful Salvage

Some of these burdens on the makeshift vehicles told a more poignant story. In hand- harrows, pushed by two nuns, were two old sisters so far gone in age and infirmity that escape on their own feet was impossible; in another hand-cart a man was pushing all his portable belongings, his child, and his wife, who was dangerously ill. The woman was still alive, but what would be her-condition at the end of that way of sorrow the mind refuses to consider. Yet another barrow was being wheeled by a widow; on it sat a little fair-headed girl, suffering from an abrasion on her forehead. Beneath a man's jacket at her side projected the blood-stained legs. of her small brother. The woman, too, was wounded. The tiny party had been struck by shrapnel as they made their way out of Antwerp; the boy had been instantly killed, but the mother and sister had miraculously escaped.

Some of the bundles these desperate people carried away with them were no less poignant in their significance, because in their poignancy there might have been, in a time less tragic, the hint of laughter. In the terror of their flight the fugitives snatched at the first things coming to their hands. Women carried, with all the resolution of those salving treasures, trumpery domestic vases and ornaments; a man trudged along with the shovel that had been in his hand when he had fled from his job at the gasworks; an old woman clung desperately to a battered coffee-pot, so damaged as to be useless; in many of the towel-wrapped bundles there was nothing else but useless kitchen utensils, the means of preparing food, but none of the food for which the starving people were craving.

Sir Galahad Uhlan

Many of the frailer and more aged women died of terror, starvation, and exposure on the road .At night the people camped out in the open, without shelter of any kind, and frequently without fire or food. And sometimes their position was made more fearful by the presence of the Germans, although the Germans were not always brutal. One young married woman left Antwerp with her tiny baby and a child just able to toddle, forgetting, in her frantic hurry, to catch up cloaks for herself or her children. On the first night of her wandering she caught sight of a Uhlan patrol, and hid among some bushes, in dread of what horror would happen to herself and her mites if they were seen. With a beating heart she crouched silently until the patrol should go by. The patrol drew level with her, and at that moment her baby wailed. The Uhlans came at once, she was found, and one of the troopers a lantern into her eyes. She felt that she was dead. In the midst of her terror a surprising thing happened. The Uhlan saw her uncovered baby, and at once took off his own cloak and offered it to her for the child. The woman refused help from the hated German, but he left her in peace, and later, wrapping the baby in her skirt and the other child in her petticoat, she tramped on again, to reach the frontier exhausted hut safe. The tale of another young wife makes more pitiful reading. During their flight from Antwerp her husband fell dead at her side under the spattering rain of shrapnel, and, with grief tearing her heart, the young woman pushed on, for, whatever her loss, she had three children to safeguard. She reached Holland safely, and there lost her two eldest mites. Frantically she is searching for them. Are thev alive or are they dead? she is constantly asking herself. In that vast welter of refugees it seems impossible to hope of finding them, so, bereft of husband and children in one heart-breaking series of days, she has only her tiny baby left to her and her memories.

Torture and the Scourge

Sometimes to the torture of flight is added the scourge of sheer brutality. A woman sat up in a perambulator in which her son was wheeling her. The boy was the only one of six children left her, and she told a terrible tale. Her eldest daughter was seventeen, her youngest four years old. German soldiers had asked bread, but the mother had told them she had only some bread for her six. "Then you have too many children," had been the reply. "Place them there in that courtyard." The oldest, a beautiful girl, on the left, the youngest on the right. And one by one the other four were shot before the eyes of the mother. "Now you haven't too many children," the barbarians had cried, and they left the house, taking with them the girl Such things are not imagined by a mother.

The Pangs of Separation

The pang of loss harrowed the length of these painful and pitiful flights. Families were broken up, fathers became separated from children, wives from husbands, in the wild movements of frantic people wives and children were left behind, and as the train slowly tore their loved ones away from them, their distraction at the separation was piteous and heartrending. Innumerable children were lost altogether in the crushes along the roads and in the trains, and Holland now is full of weeping women looking for their babies, and babies not knowing where their parents are, sometimes so young as not to know their parents' names. Man and wife, too, have been torn apart. A priest brought a man into a shelter for fugitives, and said to him, "Eat something, my friend. It will do you good." The man sat down, and the helper took him a plate of soup. Suddenly he jumped up, and with a voice full of sadness said, "No, no, Meneer de pastoor, do not be angry, I cannot eat. I must look for my wife and children."

The Amsterdam newspapers are opening their columns to those seeking children and relatives, and the windows of the station telegraph offices are full of n6tiees ma king rendezvous for those who have become separated in the flight. And not official windows only, the walls of houses at conspicuous points have been chalked over with sad an-d moving messages to missing dear ones. On the walls all over Flushing there are chalked such messages as, "the familv Dupont is at Middelburg," or that "Jeanne and Marie await their parents at the station." Mute messages, meaning so much, - to find an answer - when ?

The War Babies

But there are happy meetings. Sometimes the fortunes of flight bring the lost together. As one motor lorry entered a town in Holland a woman stood up suddenly and threw out her arms; she uttered a cry, and waved her hand to a group on another lorry. She was too overcome to speak, but on the other lorry a man heard, stood up, looking about wildly. In a minute he saw her, and as their eves met the man burst into tears. They were husband and wife, and they had seen nothing of one another since they left Antwerp. The lost children, too, are not always altogether unhappy. Holland has opened her great heart to them. The Dutch people are burning to help. One man, a hotel porter, already possessing a large family, and struggling to provide for them on a low wage, was one of the first to house such a baby. How could he do it with means so low and so strained? he was asked. "One little mouth extra among so many makes not much difference," he answered humbly, "and we must all help." Even people of better means are complaining about these babies: "we all want one," they say, "and there are not enough to go round."

From a Land Ruined for Valour

Yet, in spite of all this great charity in Holland and here in England, the travail of the heroic race continues. Hosts of the homeless pour across the Channel to this country, and are met and assisted by our own great committees of helpers. But they have lost all. They are not only homeless and penniless, but they have left behind them a desolate land smoking with destruction. They are units of a tragic legion from a land ruined for valour. They are writing for us across our very streets a message that may not go unread. We must return full the native security they have lost, and the homes they have been torn from. That is our task : see that we do it.