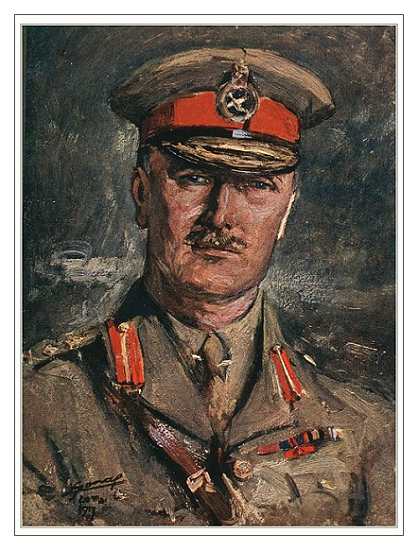

- from 'the War Illustrated', 12th October, 1918

- 'General Sir Edmund Allenby'

Men and Cities of the War

two portraits - photo and oil-painting

If you could persuade him to dress up in chain armour he would look very much like a twelfth-century Crusader. He is more than common tall, well over six feet, and broad- shouldered in fitting proportion. I am sure he could swing a battle-axe with dire effect.

Nor would his features contradict the resemblance. The square face with domed forehead and resolute jaw-line might well have belonged to one of Coeur de Lion's Norman knights. It is a face that proclaims character, the character of a man who pushes through whatever he undertakes ; who is energetic, self-reliant, enterprising. If it were not for the kindly eyes and the frequent smile, you might suppose him as ruthless in his methods as some of those earlier Crusaders. They reassure you that "the Bull" has another side to his character. He is famous for his "charges," but all who know him will bear witness also to his good-nature, to his even temper and sense of fun.

Such is the man whose name will be linked in history with those of King Richard of England, King Louis of France, and the other leaders of the earlier effort to free the Land of the Holy Places from Moslem rule. He was born fifty-seven years ago, comes of an East Anglian family, was sent to Haileybury, passed well into and out of Sandhurst, and in the early 'eighties joined the "Skillingers," the 6th Inniskilling Dragoons.

Disregarder of Convention

The luck which put the young cavalry subaltern into this regiment had something to do with his rapid success in his profession. He would have risen anyhow. Nothing could keep such a man down. But the fact that the "Skillingers" had no "frills," that they were kept abroad, mostly in the veldt in South Africa, for a great many years on end ; that the officers lived the lives of soldiers, not of loafers in English garrison towns, had an effect upon young Allenby. It helped to bring out the stuff he had in him. He developed a healthy disregard of convention, a common-sense habit of taking the simple, natural course, even though it cut through stubborn traditions.

Thus he worked at the War Office in hot weather in his shirt sleeves. One morning a fussy, self-important visitor looked in and expressed his surprise.

"This is nothing," Allenby said. "If you'd, dropped in later when the sun gets really scorching, you'd have probably found me minus several other garments as well."

“Might be a prosperous stockbroker,'' was said of him while he was Inspector of Cavalry. This was after his long term of service in South Africa, with spells of lighting in Bechuanaland and Zululand, and after the South African War, throughout almost the whole of which he commanded his regiment. He was one of our most successful cavalry leaders out there, and along with his skill and judgment he displayed an unusual indisposition to put himself forward. When the troops entered Barberton, Colonel Allenby was asked to take the lead. "My men and their horses are fatigued," he said, and the regiment rode in quietly next day.

After the South African War he commanded the 5th (Royal Irish) Lancers for a time, and then was given the 4th Cavalry Brigade. As brigadier he was effective and still unconventional. At manoeuvres he asked one of the umpires some question. "I'm not here to give information," was the testy reply. " No, no," said Allenby, looking him up and down ; "of course not. I ought to have realised that you are here for ornament ! "

Leap to the Front Rank

Allenby was a "coming man " clearly when he was at the War Office, and the war gave him an opportunity to leap straight into the front rank of the distinguished soldiers of his generation. He was given command of the Cavalry Corps in the Expeditionary Force, and it was the ability with which he covered the retreat after Mons that chiefly saved us from disaster. With his 4,000 troopers he spread out a network of patrols and small columns over a front of twenty-five miles. Field-Marshal French didn't overstate General Allenby's services when he wrote in his despatch :

"The undoubted moral superiority which our cavalry has obtained over that of the enemy has been due to the skill with which he turned to the best account the qualities inherent in the splendid troops he commanded."

The management of that retreat made Allenby sure of his powers. He had proved now that he possessed the highest qualities both as tactician and as leader of men. It was very difficult work to keep the enemy off while our guns and infantry went back and back and back. The general had one narrow escape himself. An encircling movement was attempted by the German cavalry. Allenby rode hard all one night with a French guide and with the best part of a cavalry division following as hard as they could. Luckily the tired Germans stopped just when they were on the point of rounding up the British force, which got safely away.

Arrival in Palestine

Early in 1915 General Allenby "pulled the situation out of the fire" at the Second Battle of Ypres. I was in Russia then, and for long afterwards, but I was back when "the Bull" charged the enemy in the Battle of Arras, and charged so fiercely that in twelve hours 11,000 prisoners had passed through his corps' cages and he had captured 145 guns. He had been an army commander then for two years. The Third Army was his, that which has done so magnificently under Sir Julian Byng. He stayed with it until the summer of last year, when he went out to take command in Palestine.

He found the Turks strongly entrenched, and our men entrenched just as strongly opposite to them — position warfare in its most tedious form. Headquarters had been in Cairo, 300 miles away, and it seemed as if stagnation might continue for ever.

With Allenby's coming the atmosphere changed. He declined to stay in Cairo. He trundled across the desert in a Ford car, and set up his headquarters in a wooden hut ten miles from the front line.

He set to work at once to organise railways and make roads. He commandeered all the beer in Egypt for his thirsty troops and road-makers. In four months he had prepared a heavy blow, and he struck with full assurance of its taking effect. On the last day of October he took Beersheba ; on November 7th Gaza fell, on November 17th his forces were in Jaffa, December 7th saw Hebron occupied, the next day Jerusalem was in our hands.

This was an excellently planned campaign. The design unrolled itself piece by piece until the final objective was reached. Those about him during this time said that the general was never elated when things went as he had planned them, never depressed if they went a little wrong. He gave the impression not only of knowing exactly what he was about, but of knowing what the enemy's thoughts and intentions were also, and of being confident that all would go well.

After this came a long period of quiet. Allenby was preparing another blow. The Turks were terribly afraid of this new British commander. "Allah nabi" they called him, which, in Arabic, means "the man sent by God." They were afraid of him, but they did not understand him, or they would have known that all the time he kept so quiet he was making ready to fall upon them unawares.

A Napoleonic Elan

Long ago he had declared that the best way to outwit your enemy was to do something which he did not think you likely to attempt. Now he made ready with patience and thoroughness of preparation to carry out a daring strategic plan of which neither the Turks nor their German advisers had the least suspicion.

It was Napoleonic in its simplicity, in its daring, in its success. With a rush "the Bull" broke through the enemy's front, then, with the instinct of a cavalry leader, he sent all the horse he could collect through the gap. As a finished operation it is the finest thing in the war, excepting Tannenberg. Two armies were utterly broken. A third was scattered. Sixty thousand prisoners and hundreds of guns were taken. Palestine was by this one blow cleared of Turks. The road lay open to Damascus.

A really great victory, and one that will make Allenby's name famous for all time. There is something, in the freeing of the Holy Land which sets the imagination afire. I met the other morning a hardened politician of my acquaintance, a former Cabinet Minister. He was reading a newspaper as he walked, and there were tears in his eyes. "Have you seen it ?" he asked, pointing to an account of the Thanksgiving Service in St. Paul's Cathedral. "Nothing has moved me so much for years."

History will link Allenby's name with this great event, and, if it be well informed, it will tell how the victory was won by a man who is first, last, and all the time a soldier, a student of war, a born leader, hard as nails himself, simple in his way of living, no time-server, no politician, no puller of social wires, owing nothing to favour, nor to anything but solid ability and steady deserving.