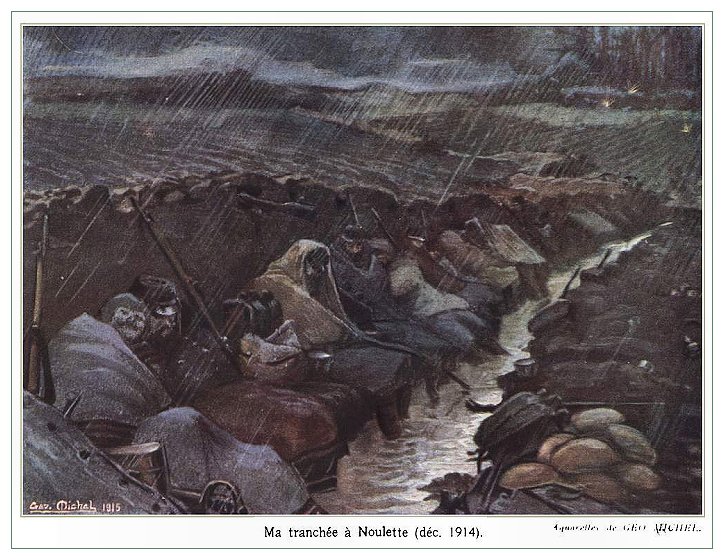

On the French Front in 1915

This series was published in the french newsmagazine 'L'Illustration'.

A FIRST VISIT TO THE TRENCHES

By

WILFRID EWART

The morning of February 23rd, 1915, breaks cold and misty. Picture to yourself my billet, a dilapidated farmhouse by the roadside, which seems to be in the centre of a wide plain. Everything is very dirty - that is the first impression. The farm buildings, as always in this country, are grouped around a square courtyard with a midden in the centre, a midden that reeks of damp manure. Everywhere mud, slush and water, ankle deep. In the farmhouse itself two rooms are habitable-the one a kitchen containing a table, a number of boxes (used as chairs) and a cooking fire, usually struggling for existence on the hearth; the other, a rather smaller apartment with a brick floor, which is lived and slept in by the two company officers. One must confess it is a cheerless room. There is barely space for a table and a couple of broken chairs. The window, which looks out across the road to a vista of plough-land, willows, and flat, dreary fields, has lost several of its panes, which are made good by rather inadequate sheets of brown paper. The walls are peeling from chilling dampness. There is no room for a fire here. To get and keep warm one has to stay in the kitchen, where with the servants one crouches round the struggling flame.

In barns and outhouses, whose interstices and gaps are numerous, the men are billeted. Behind the farm is a very water-logged orchard which is used as a parade-ground. So deep, clinging and sticky is the mud that everywhere one has the greatest difficulty in moving about.

Such are the Brigade reserve billets, a little over a mile behind the trenches, which are occupied for four days. The Battalion, having come out of the firing-line two nights before, is due to go in again two nights hence, after which it returns to what are known as Divisional or "rest" billets some two and a half miles farther back.

After a breakfast consisting of porridge, bacon and poached eggs, bread, butter and marmalade, we go out on parade. To an eye accustomed to the niceties of King's Guard and soldiering in London, the men appear war-worn, variegated and ragged. What else is to be expected? Their khaki, clean and free from mud though it is, has turned many different shades of colour, so has the equipment. The caps are in many cases different, some men wearing woollen sleeping caps, others the regulation head-gear. These were the days before steel-helmets, and regulation caps were not always easy to obtain. But, considering the vicissitudes to which their clothing is subjected, the men (of whom it is always expected that they shall spend their time in reserve billets chiefly in cleaning up) turn out most creditably.

Not a sound breaks the stillness of this misty winter's morning save the singing of larks and the sharp words of command of the platoon sergeants, drilling their men. But for something lacking in the appearance of the countryside one might easily imagine oneself in England. What a contrast to previous conceptions of "a mile behind the front," where one had imagined the guns to be always booming and the clatter of machine guns and rifle-fire to be incessant But this morning, except when an aeroplane sails lazily overhead, there is no sound. Perhaps the absence of visible life is the nameless something which appears to be lacking in this utterly featureless countryside: not a human being in sight save an occasional soldier walking along the road; not a bird or animal save the rising larks, and a distant string of artillery horses.

In the early afternoon there is an inspection of the newly arrived draft by the Brigadier-General. After the inspection, which takes place in a field behind Battalion Headquarters, the Brigadier makes a short speech in which the vital importance of discipline in trench warfare is impressed upon the men and they are exhorted to follow in the footsteps of their forebears, the heroes of the Retreat from Mons, the Aisne, and the First Battle of Ypres.

That evening, I learn, is to provide my first experience of the trenches. I am detailed for a working party.

It is time to start on the first trip to the trenches. Nor, with the sombre winter's evening falling, is the prospect a particularly inviting one, despite a natural curiosity and the excitement born of long anticipation. There lies before us a two-mile walk, a long night's work and, for the newly-joined ensign, a number of unique experiences.

It is four o'clock. We parade in the road-it is said a German machine gun sprays the first crossing-and set off. Soon we take to the fields. The men have spades and rifles to carry, and it is not long before we struggle knee-deep in mud and fall over strands of barbed wire and into holes. Having drawn extra tools from a shattered barn, we take to crawling.

"Zip!" There is no mistaking the sound; the first bullet I have heard in the war whistles overhead with a peculiar clear-cut twang. One feels interested rather than frightened, for obviously the sergeant and the men take bullets as a matter of course. We are in the machine gun zone. The sergeant says: "You had better double along. Keep down here, sir." Bright moonlight makes these three hundred yards of exposed ground as clear as day.

A little farther on an engineer officer is waiting to point out work to be done. Two sections of trench have to be linked up by a third which is to run over the crest of a small hill. After getting the men strung out in a long irregular line and setting the N.C.O.'s their appointed task, I make my way along a rough breastwork which has been built up as a temporary protection. The English front-line trench is on the forward face of the little hill. Here I find an old machine-gun emplacement in which occasionally to sit down and rest, whence may be obtained a view of the working party on one side and across to the German lines on the other. No Man's Land spreads in between.

Many a night subsequently was I to look out over a similar scene, but never did the details of the picture impress themselves so vividly on my mind as upon that first visit to the trenches. And suddenly out of the long silence there came the obscure reminders, the swift stirrings of war: the faint clink of spades away down in the trench where the men are working, stertorous masculine breathings, a muttered exclamation, an occasional curse. Sometimes a stray bullet whistles out of the darkness and goes singing on its way; sometimes a party of soldiers, heavily burdened, tramps by, crouching low. Often - about the middle of the night-a machine-gun speaks with its metallic "clack-clack," or the sharp crack of a rifle comes from near at hand, or somewhere afar off a great gun booms sullenly. Then silence, and one listens intently. Always there is a feeling of tenseness and expectancy. Only the "click-clack" of our picks and shovels at work and eighty yards away the answering "thud-thud" of the German wiring parties driving in their stakes!

Then, rising and creeping to the parapet of the little fort, I peer over, my head and body partly concealed by the sandbags. The ground slopes sharply away to the confused region of moon-light and shadows. At first the eyes cannot probe this dusky space. Yet after a few minutes you make men out-flitting here and there, fetching, carrying, digging, working like demons, bent figures silhouetted in the moonlight. They look rather like Cossacks from famous pictures of 1812. And occasionally the non-commissioned officers can be heard cursing those grey soldiers of the Fatherland. There is a partial truce between us. By night everybody works at that part of the line; by day everybody fights desultorily.

And, looking out for the first time across that country so dark and shadowy, so pregnant with fate for us all, the strange baffling mystery of it confronts one. Now and again the crack of a rifle breaks the stillness, and at intervals there comes to the ear the infernal "clack-clack" of a machine-gun, than which there is no sound more sinister in war. 'Twas on such a clear moonlit night, when a fresh wind blew to the nostrils the first scents of spring, that a man working in the midst of his fellows fell silently to the ground - ripping blood - nor ever spoke again. That is the impenetrable problem, the everlasting mystery of it; experience can go no further. The interminable lines of watching men stretching away into the dim distance towards the battlefield of Ypres, where the guns boom and the machine-guns chatter all night long-the interminable lines of watching men quenching their fears (of each other) as best they may, awaiting their chance to kill, to wound-for why? For what? "For some idea but dimly understood?" The same blood, indeed, the same God, the same humanity, the same mentality, the same love of life, the same dread of death - one could not hate them, one could only wonder - and pity.

And as I watched that night, there came to my ears the sound of a man singing. Do you know the curious quality of a man's voice heard at a distance? Strangely the voice rose and fell on the wings of the night; it was joined by others, and the Germans began to sing "The Watch on the Rhine" and the Austrian National Hymn. This, as I learned later, happened every Sunday evening. On an off-night they would have been "strafed," but now all was still. And often afterwards there would come from the enemy trenches - generally, as I subsequently learned, to screen some particularly important work they were engaged upon - strains of wild, windy music, like the sighing of pine forests, such songs as the Southern Germans love. And every now and then there came, to, the sound of a mouth-organ, cheap and bizarre, to remind one of a cafe chantant in Paris, or - why I know not - of the hot mid-day in some London street.

Soon after midnight our task is finished, and we trudge back to billets beneath the waning moon, towards a darkness in which there is as yet no hint of dawn.