An Amateur Journalist in Belgium

CHAPTER X

ANTWERP

All passes having been refused to military correspondents in France, and the French making themselves daily more disagreeable to the journalists whom they picked up in the war zone, my paper, the Daily Telegraph, determined to send me to Russia. But before I could make arrangements for going to this new field, events took a definite turn at Antwerp, so I was hastily ordered to cover that beleaguered city.

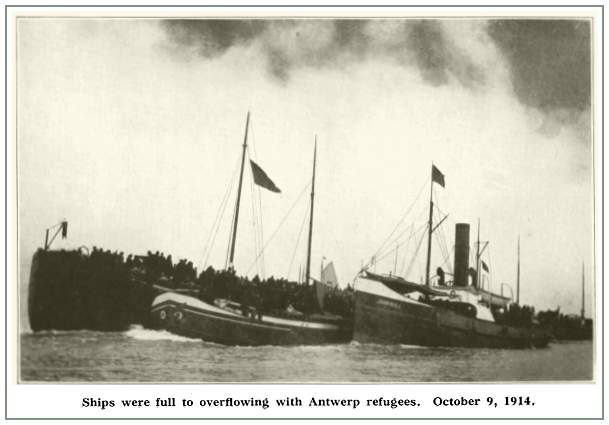

When I arrived in Flushing it already harboured several thousand refugees. Pale, haggard, and many of them still with nerves vibrating from the sound of the shells, they crowded into the little Dutch port, hoping to find there a haven of safety. Every train from Roosendal brought more of the refugees. All day, boat after boat had steamed down the river crowded to the rails with those who wanted to escape from Antwerp.

As yet the city had not fallen, but the Germans had brought guns that had a range of five miles up to their advanced positions, and with these they could reach well into the centre of the city with deadly projectiles. Somehow the news that the English and Belgian forces that were defending Antwerp were about to evacuate the city, leaked out, and the citizens thinking themselves abandoned to the enemy, became the victims of their own terror.

Escape was their only thought. When the bombardment began it was the signal for such an exodus as before seemed impossible outside some sensational book of fiction.

Men and women fled before a fear of death in frightful form. That fear was plainly written in the face of every citizen of Antwerp. I remember seeing a young, pale, but rather pretty woman who sat alone in the station refreshment-room. This room had been the centre of a clamouring throng for hours. I noticed her sitting alone, and as I entered the refreshment-room for the first time, a solicitous waiter placed coffee, a sandwich and some scrambled eggs on the table before her. She did not seem to notice the food - her dark eyes looked steadily off into space as if picturing some vivid terrifying scene of the bombardment. After getting something to eat myself, writing a dispatch and taking it to the local telegraph office, all of which occupied a couple of hours' time, I again returned to the refreshment-room. There was the girl (she was in the early twenties), sitting as I had first seen her, the food untouched, her unseeing eyes turned back on the scene of the night before.

From the moment the first shell fell in Antwerp the whole population was seized with panic. The streets leading to the railroad station were crowded with a frightened struggling mob, pressing onward to escape the hail of iron and fire. Actually, the shells reached only the southern section of the city, and did little damage there. The great oil tanks which stood in the danger zone had been emptied, the petroleum being turned into the river Scheldt. They had been set on fire, however, and what remained of the petrol was burning murkily. A few houses had caught fire from the hail of projectiles.

One of the most pathetic among the many little groups of refugees was a woman with two small children, girls, four and three years old. In the flight from Antwerp the rule that holds on a sinking steamer was put into effect - " Women and children first !” Because of this rule a number of women found themselves without male protection, stranded in a foreign country. The woman to whom I refer had been, with the two children, pushed on an already overcrowded lighter as it was towed away from the wharf. With a voice of anguish she asked advice of me as how she might again find her husband. I could only suggest that she should advertise in the local papers. While she told me the tale of the bombardment as she had witnessed it, she spoke of the soul-piercing shriek of the shells and the never-ceasing boom of the cannon. When she said cannon, the elder girl looked up, tears sprang to her eyes, and she said piteously, "Pas plus de canon, maman, pas plus de canon."

When I arrived in Flushing the information I gathered from the refugees led me to believe that Antwerp would not be evacuated for two or three days. Therefore I arranged with an old Dutch tug master to take me up the river to the besieged city the next morning. It was arranged that we should start at daybreak. It was still night when I stumbled down to the wharf-side and clambered over two other crafts to the deck of that tug John Bull. Mysterious and ghost-like, the crafts crowded into the little harbour looked in this hour. Not a star showed, and where I knew the river flowed, was abysmal blackness. I was still sleepy, so using my dress-suit case for a pillow I lay down in the stern-sheets of the tug.

Soon I saw a sturdy short figure emerge from the bowels of the tug, looking for all the world like a gnome. I recognized Captain Hermans. With the first streaks of grey dawn the tug churned its way out into the broad mouth of the Scheldt. Steaming up the river under a leaden sky, the bow of the tug cutting through the waters like a knife, I witnessed a panorama of history. As far as the eye could see a stream of vessels rushed down upon me. In the distance they looked like a ghostly armada. Every type of craft was there-transport, tender, lighter, trawler, collier, coaster, yacht and hulk, followed in a procession that lost itself where the sky met the waters. All the ships followed the same course. Over the quiet waters came the distant boom of cannon. The ships were fleeing from that sound. With my glass I was soon able to make out the human freight the vessels carried. They swarmed over the decks. Some even climbed into the rigging. Soon the John Bull was among them. I could see the faces of haggard women. I could hear the cries of frightened children. All stared in wonder as we passed. Some shouted the question where we were going.

"To Antwerp," answered Captain Hermans.

"Turn back! it's burning! The Germans are there! Turn back!"

The words carried over the water a wailing note of alarm. Without heeding this warning we kept on. I had hopes of reaching the city before it fell. When the John Bull arrived at Lillo, hardly seven miles as the crow flies from our goal, we heard that Antwerp had fallen. A captain of a Belgian river patrol boat stopped us to give us this unwelcome news and forbade us to go further. As the spire of the famous cathedral of Antwerp was in sight, to turn back was indeed a disappointment.

From Belgian soldiers I learned that the British and Belgian forces which had been holding the city began their evacuation the previous night. In the confusion of this night march, part of the English force wandered over into Holland and were there interned. The main body of the defenders retired in a most orderly manner, reluctant to leave this city which they had so gallantly defended. Among the very last to depart was the King Commander.

In my opinion the holding of Antwerp was a strategic error.

When the Belgian army retired to Antwerp it was supposed to be falling back on an impregnable position, from which it could threaten the enemy lines of communication. In fact, Antwerp was not impregnable, as was conclusively proved, and the Belgian forces made only two sorties against the German communications. Thus during the period when it would have been a factor of importance if joined with other French or English Corps, because it was isolated, its influence on the development of the early campaign was almost negligible. This is a lamentable fact. Not for one moment did this considerable force check the onrush of von Kluck, or weaken the blow aimed by the German advance against any part of the French line. This inactivity, however, is forgotten in the splendid fighting of the Antwerp army in the defence of the Yser.

As a further reason for the abandoning of Antwerp, I advance the theory that a fortified city is a military weakness. This has been proved time and again in the present war. Liege, Namur, Maubeuge, and Antwerp indicate the truth of my contention. Since the extraordinary range of modern artillery has made it possible for siege batteries to pour shell down upon a defenceless populace from positions far beyond the outer ring of defending forts, all fortified cities have become hopelessly vulnerable. Now that the homes of inhabitants may be inflamed by fire bombs, what is gained by surrounding any city with walls and ramparts?

The engineers who planned the defences of cities twenty years ago, failed to reckon on the genius of Krupp. They could not foresee the devilish ingenuity of the German. In fortification we have a modification of the armour-plate and projectile penetration problem. Ramparts erected a score of years ago were proof against any shell that artillerymen could then conceive of. They never dreamed that it would one day be possible to hurl a ton of iron and explosives a distance of ten miles. Yet this is what is claimed for the German 17-inch mortar. And what is the value of any fort when air-craft of every sort can fly over them and drop bombs at will?

Another handicap of the fortified city is the fixed line of defence. This line it is certain is well-known to the enemy. The German gunners' map of Antwerp have ranges accurately scaled off from the forts to every possible gun position before them. This makes for a fight between the seen and the unseen. When the turret of Fort Waelhem was destroyed, not a German had been seen by the men in it-that is if we except one in a Taube. The Belgians there first knew they were under fire when two or three random shells fell in the vicinity. Then the air-craft circled over their heads. Down came a naphtha bomb, fair in the wall of the fort. A cloud of stinking smoke marked the spot. This made a perfect target. In five minutes the turret cracked under a rain of iron. The shells fell like meteors from a cloudless sky. Such is the effect of indirect fire. It is difficult even for the trained eye to discover the positions of howitzer or mortar battery using high angle fire. Under it a novice artilleryman is helpless.

Again, the one-time advantage in calibre and range which fortress artillery possessed has disappeared. In fact, the siege artillery brought into action by the Germans has nearly always been superior to the defenders' cannon. This is another strong argument against fortification, at least against fortification that has not kept pace with gun improvements: and no fort I have seen in Belgium can be classified as modern. A great deal of misinformation has been published on the strength of the fortified cities that have been so easily taken by the Germans. It may have been policy to overrate these forts in order to deceive the enemy, but the misinformation had the effect of creating confidence in the impregnability of the defended cities that events did not justify.

When this confidence has been destroyed by German success, the moral effect on our people and even on our troops has been bad. The impression among the Belgians and French is even worse. Since Antwerp fell, the unthinking will consider German artillery as more destructive than an earthquake.

Is it not better to admit that the turret and concrete fort, as conceived and built by General Brialmont has proved to be a complete failure? Concrete, even when reinforced, cannot stand against modern shells of large calibre; and in the peculiar type of fort that defends Antwerp, once the concrete is cracked, it becomes impossible to operate turret machinery. Thus one well-placed shot will put two guns completely out of commission. There are two guns in each turret. The concrete chips get into the groove in which the steel semi-spherical hood revolves, and jam until it is no longer possible to turn it. This one defect should be sufficient to condemn this kind of construction.

But the concrete fort has two other fatal weaknesses - the first is the mistake of making the fire-control and observation tower serve also as the searchlight station. What better target could one want at night than the glittering disc of a searchlight? and if your light is hit, your observation station is destroyed. This error in fortification building is nothing compared with the final fault of the Brialmont turret fort. This is the light shaft. After devising an intricate system of subterranean tunnelling in his fort, and covering it with a heavy wall of concrete, Brialmont leaves a sort of chimney 2 feet square opening into the very heart of the defence. The light shaft opens directly over the ammunition cell. I saw Fort Loncin at Liege after a shell had dropped down the light shaft. It could not have been more disrupted by an earthquake. Nothing remains but a heap of rubble. Both turrets were torn from their foundations and up-ended. The concrete walls were so much slag; perhaps this was a lucky hit. Even so, other lucky hits will find the same vulnerable mark. A soldier of the Namur garrison told me that much the same thing happened in the fort he was in.

Again, no gun I have seen in a turret fort was larger than 15 cm. calibre. I understand that larger guns were ordered for the forts at Antwerp, but as war opened before they were delivered, Herr Krupp has kept them for home use. Also the concrete for many of the Antwerp forts had not arrived before the city was invested. The turret at Fort Waelhem and Fort Wavre, Ste. Catherine were defended by sand-bags only. Under the circumstances it was brilliant work that they held out as they did. At Fort Waelhem a copper brewing vat was set up as an imitation turret, and it drew considerable German fire.

But leaving the special defects and getting back to the general question of fortified cities, the fatal defect in the whole theory is that it leaves the garrison exposed to capture. The war of 1870 demonstrated this, time and again, and in this war many good soldiers were made prisoners when Maubeuge fell. Luckily the handful of English and Belgians holding Antwerp found a safe line of retreat when the forts crumpled beneath the enemy's fire. Those interned in Holland are but a small part of the defending force.

I have already mentioned the weakness of the civil population in a fortified city. Since the Germans have degraded the noble profession of arms by throwing shell and shrapnel among women and children, the inhabitants of the city open to bombardment are doubly unfortunate. It is hard to keep the terror that spreads among them from lowering the morale of the defending garrison. Very rightly General Paris directed that all civilians should leave Antwerp.

In the taking of Antwerp, the Germans achieved more of a moral than a material victory. Under the present circumstances the city has only a limited strategic value. The neutrality of Holland destroys the city's military worth, but how long will Germans respect that neutrality ?

December 1914