LIEUTENANT-GENERAL JAN WILLEM

JANSSENS

by Geert van Uythoven

Early career

Jan Willem

1) Janssens was born on 12 October 1762 in the city Nijmegen in the eastern

part of the Dutch Republic. His military career began when he was nine years old,

when he entered the Dutch army as a cadet in the infantry Regiment 'Van Aylva'

in 1771. The regiment renamed 'Van Burmania' on 24 December 1772, Janssens

entered 'real' service when he was eleven years old, March 1775. His presence

with the regiment lasted longer as its colonels; on 12 September the regiment

was renamed 'Prince Frederik van Oranje-Nassau', and in this regiment Janssens

became an ensign on 5 February 1777. Again, the regiment was renamed, and

became on 5 November 1784 Regiment No. 1 'De Schepper'. On 5 April 1785

Janssens became quartermaster of the 2nd battalion of his regiment. During the

patriot rising in Holland in 1787, the regiment choose the side of the

Stadtholder, and remained in the province Noord-Brabant during the Prussian invasion,

missing action 2). Probably because of staying on the victorious side, on 31

December 1787 Janssens was promoted 1st lieutenant. However, finally he would

leave the regiment, to become a captain on 12 December 1788, commanding the

grenadier-company of the 2nd battalion / Infantry Regiment No. 18 'Van Pabst'.

His rank became effective two years later, on 25 February 1790. Regarding the

colonels, the same pattern continued; in April 1793 the regiment was renamed

'Von Wartensleben'. Janssens served during 1793-'94 with the regiment in

Flanders, in the campaign against the French. On 13 September 1793 he was

wounded by a musket ball in his right shoulder, during the capture of Menin. He

took part in the siege of Lanrécies (20-30 April 1794), and the battle of

Fleurus on 26 June 1794.

After the

defeat of the Dutch and British troops by the French in the beginning of 1795,

the Dutch Republic was changed in the Batavian Republic, a French satellite

state. The Batavian army was reorganised along French lines, and Janssens

regiment, much depleted by the heavy fighting, became the 3rd battalion of the

1st Halve Brigade ('Demi-Brigade'). However because of his wounds,

received during the above campaign, Janssens was pensioned out of the standing

army, and assigned to the administration of the French troops present in the

Batavian Republic on 16 June 1796 3). His administrative capabilities soon came

to the surface, and already the next year, on 11 March 1797, Janssens became

First-Commissary of the Administration, and entrusted with a number of missions

to France in 1797, 1798 and 1800. On 29 March 1800 he became secretary of the

Department of War, but resigned this post on 10 October 1800, staying advisor

of the Agent of War. On 29 January 1801 he resumed the function as

First-Commissary of the Administration of the French troops in the Batavian

Republic.

General Jan Willem Janssens

Cape of Good

Hope, 1802 – 1810

Following

the Peace of Amiens on 25 March 1802, the Cape of Good Hope, captured by the

British, would be returned to the Batavian Republic. Already during the

preliminaries before the peace was signed, on 18 February 1802, 39 years old

Janssens was appointed Governor-General and Commander in Chief of the Batavian

colony at the Cape of Good Hope. He received the rank of Lieutenant-General in

the Batavian Army and a salary of 50,000 guilders, a big achievement for

someone so young, even during this era, and in addition promoted from Captain

to Lieutenant-General after having fulfilled only administrative functions!

Discharged honourable from his function as First-Commissary on 28 May, it would

last until 5 August before he left for the Cape of Good Hope, sailing on the

'Bato', part of the squadron commanded by Rear-Admiral Dekker. The squadron

arrived at the roads of Capetown on 24 December 1802, and on 21 February 1803

Janssens took over government from the British. Expecting that peace would not

last long, he immediately ordered defence works to be raised and existing ones

strengthened. And as he expected, the Peace of Amiens was short-lived and on 16

May the British declared war again. Janssens was however ordered to send most

of his garrison to Java, which possession was estimated of more importance by

the Batavian Government then the Cape of Good Hope. All that was left to him

were 1,900 men, Batavians and the 5th Waldeck Battalion in Batavian service,

augmented by a few hundred trained Hottentots 4). However, it took some time

before the British would return. Only on 4 January 1806, General Baird landed

with 10,000 men at the Tafelbaai, near Capetown. Capetown, defended by the

Waldeck battalion, surrendered and was occupied by the British. Janssens

retreated with about 1,500 men remaining, making himself no illusions about his

chance to defeat the British. On 18 January, a battle was fought between the

British invaders and Janssens, at the plain of Blauwberg. Janssens lost,

receiving a concussion to his right hip by a musket ball during the battle, and

was forced to capitulate on 23 January. Permitted to leave for the Batavian

Republic with his garrison on British ships Janssens left Capetown on 5 March.

He arrived in his homeland at The Hague on 8 June 1806.

Things had changed during his absence. Napoleon had decided to abolish the

Batavian Republic and to create the Kingdom of Holland, to be ruled by his

brother, Louis Napoleon, who would be known as Koning Lodewijk by the

Dutch. King Louis, needing all the support he could get, immediately recognised

the benefits he could get by winning over Janssens to his side. Offered on 11

July 1806 to become Secretary-General of the Department of War, and Privy

Council Extraordinary with the 4th Section ('War') of the State Council 5) for

the year 1806, Janssens had no reluctance to accept. One after the other,

Janssens received and fulfilled a number of appointments, but saw no active

duty: 24 September 1806, Quartermaster-General of the Expeditionary Army,

destined for Germany; 7 October, Quartermaster-General of the Army of the North

in Germany under King Louis; 4 November, Governor-General of Westphalia

occupied by the Dutch troops; 15 December, Director-General of the War Administration;

1 January 1807, Privy Council in normal service with the 3rd Section ('War and

Navy') of the State Council for the year 1807, and on 6 March also Privy

Council in normal service with the 4th Section ('War').

In addition,

Janssens was distinguished for his good conduct by being appointed a Knight in

the Koninklijke Orde van Verdienste ('Royal Order of Merit') on 1

January 1807 6). On 28 May 1807 he was confirmed in his rank of

Lieutenant-General on half-pay, receiving his payment from 19 January 1806. His

career continued: on 26 June 1807 he was appointed President of the 3rd Section

('War and Navy') of the Sate Council, replacing Dirk van Hogendorp, who fell in

disgrace because of his pro-Napoleonic feelings. Again Janssens was

distinguished by being appointed Commander in the Koninklijke Orde der Unie

on 25 November 1807. And again replacing Dirk van Hogendorp, Janssens became on

7 December Minister of War of the Kingdom of Holland. As a Lieutenant-General

he was pensioned on 1 January 1808. While continuing being Minister of War, in

addition for the years 1808 and 1809 he was appointed Privy Council

Extraordinary with the 3rd Section ('War and Marine') of the State Council. On

27 March 1809, Janssens was replaced as Minister of War because of his ill

health. On his own request, because of the same reason, on 22 May of the same

year he was pensioned as Minister of War, receiving a pension of 8,000

guilders, and retaining his rank as Lieutenant-General and his function as

Privy Council Extraordinary.

The East

Indies, 1811

Now

Janssens' life would become directly influenced by Napoleon, when he was

chosen, taking the place of Vice-Admiral Verhuell who refused, to bring the

message of King Louis' abdication of the throne of the Kingdom of Holland to

Paris on 3 July 1810. After his arrival on 22 July, Napoleon made him a member

of the Council of the Affairs of Holland. After the incorporation of the

Kingdom of Holland into the French Empire Janssens became général de

division in active French service on 11 November 1810. He was appointed by

Napoleon Governor-General of all French possessions east of the Ile de France

(in fact the former Dutch East Indies), instead of Daendels, by Imperial decree

of 16 November, and distinguished by being appointed grand officier de la

Légion d'honneur, effective the day he would accept the appointment, which

was on the 19th. On the 21st, the day of his departure, he was made a Commander

in the same Order, again changed in Knight on the 25th. He left for the East

Indies from Maindin in France on 29 December, sailing with the frigate "La

Méduse". Arriving in Batavia on Java, the main island of the East Indies,

on 15 May 1811, the next day Janssens took over from Daendels. Janssens

negative reports about the situation he found when he took over in my opinion

do not justice to everything Daendels had done during the previous years.

Although Daendels had his mistakes, he had achieved much, and especially had

made an tremendous effort for the defence of the colony entrusted to him, as

far as it was possible with the scarce means he had. This all was ready for use

to Janssens, who would not have to wait very long.

General Jan Willem Janssens

talking with native sovereigns

On 30 July a British invasion

fleet arrived north of Java. The British war fleet consisted of 43 smaller and

bigger warships, commanded by Vice-Admiral Stopford. He protected a transport

fleet of 57 ships, which transported an army of 11,000 men and 500 horses,

commanded by Lieutenant-General Samuel Auchmuty, and accompanied by the

Governor-General of the British East Indies, Lord Minto. The army consisted for

the greater part of veteran troops, and were divided in four brigades, of which

one formed the advance guard and one the reserve. Lieutenant-General Janssens

forces inherited from Daendels consisted of 11 infantry battalions, 2 jäger

battalions, 4 cavalry squadrons, a foot artillery battalion, and 3 horse

artillery companies. On paper these formed a total of 17,774 men, of which only

about 12% were European, supported by an additional 2,500 native auxiliaries.

However, in reality strength was much less, and many strategic positions had to

be garrisoned. In addition, their quality was doubtful. The field army counted

about 8,000 men, of which most were natives, with none or minor experience.

many of them were forced to enter the Dutch army and hated all Europeans, and

would try to run as soon as they had a chance. There was a huge shortage of

officers, and therefore many NCO's, mostly incapable for the task, had been

promoted to fill the vacancies. Furthermore, by orders of Napoleon, the army

was commanded by général de brigade Jean-Marie Jumel, a mediocre

commander, who spoke no word Dutch or Malay.

After

careful reconnaissance of the coast Lieutenant-General Auchmuty decided to land

his troops near the village Tjilintjing, about three hours east of Batavia. The

careful preparations for the landing, with intensive support from the navy,

appeared to be unnecessary because the landing of the advance guard on 4 August

1811 was unopposed. In accordance with the defence plans of Daendels the

'French' army 7) was concentrated between Weltevreden and Meester Cornelis,

where at the latter place an entrenched camp was constructed. Janssens had his

headquarters at Jacatra while Batavia was only defended by an insignificant

detachment. The British advance guard moved along the road to Meester Cornelis

to protect the landing of the remaining infantry. During the 5th the cavalry

and artillery was disembarked. When Auchmuty received a report that an enemy

column was advancing from Meester Cornelis -although later it became clear that

this column was nothing more then a reconnaissance patrol- his advance guard

was ordered to move about ten kilometres south to the Kapel van Suyranah.

During the march, several dead were caused by sun-stroke. This made Auchmuty

change his decision; instead of advancing inland he decided to advance on

Batavia along the coast, hoping that the advance of his troops to the Kapel van

Suyranah would let Janssens believe -as occurred- that the British would go

that way. Therefore, during the evening of the 6th, the British advance guard

was relieved by the reserve brigade, and advanced along the road to Tjanjong

Priok. Several bridges were destroyed by Daendels, but during the months that

followed his relieve most of these were replaced by bamboo made passages by the

natives. Because of this the British advance was unexpectedly swift, and during

the same evening their advanced patrols reached the place were the road crossed

the Anjol river. Arriving there, they observed that the bridge across the river

was burned, and French outposts present on the other side. To take this

obstacle in the evening of the 7th a number of navy sloops rowed upstream and

created a passage, across which between 22.00 and 24.00 hours the infantry of

the advance guard crossed the river. On the 8th, at break of day, they arrived

in front of the suburbs of Batavia led by General Auchmuty, who demanded the

immediate surrender of the city. The mayor of the city Hillebrink himself made

his appearance with Auchmuty, declaring himself willing to co-operate and

asking to spare the city and its inhabitants, in addition telling him that only

a few cavalry were left. Nevertheless, the situation of the British advance

guard was not very bright. Most of the houses were abandoned by their

occupants, and there was no drinking water available because the water-works

were destroyed. In addition, there was a real chance for a French attack from

the direction of Weltevreden. However, when the first British companies entered

the city proper the French cavalrymen retreated, and the British were not

disturbed while they extinguished the fires of the magazines, which were set on

fire by order of Janssens. In Batavia many guns and provisions were captured.

During the evening most of the British advance guard entered the city and took

up positions for its defence. It was an uneasy night for them, because the had

to stay under arms during the night, and had to repulse an attack from a strong

French column.

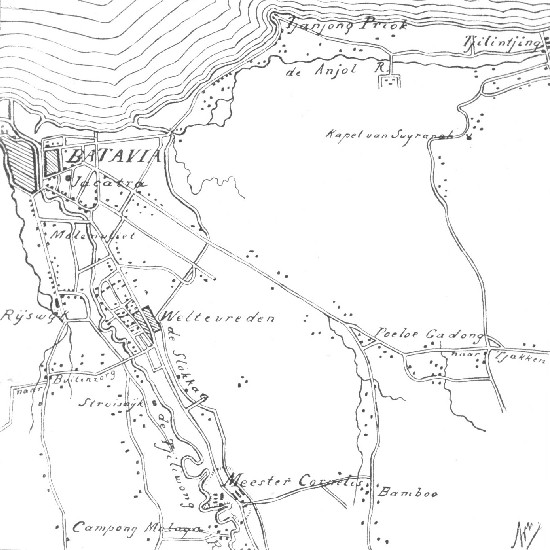

Map of Batavia and

surroundings

Already on

the 8th Lord Minto had send an envoy to Janssens -who had moved his

headquarters from Jacatra to Meester Cornelis- to demand the surrender of the

colony. Janssens bluntly refused. As a result, Auchmuty was ordered to continue

his offensive. On the 9th, the British outposts were moved forward to Rijswijk.

The next day, the bridge across the Anjol river was finished, enabling the

cavalry and artillery to cross, and the main force and the reserve to enter

Batavia also. During the following night the British advance guard moved to

Weltevreden. South of this village part of Janssens' army, commanded by général

de brigade Jumel, occupied good defensive positions, strengthened by abatis,

with the right flank protected by the Slokkan canal. The left wing was however

left undefended by Jumel, who had burned the bridge across the Tjiliwong but

had not occupied the terrain. The British advanced in the centre under heavy

musketry and gunfire, but could make not much progress because of the broken

terrain and the obstacles. But then they managed to turn the left flank, and

took an artillery battery consisting of four guns, despite the fierce

resistance of the gunners who died on the spot defending their guns. Brigadier

von Rantzau had pointed out the vulnerable position of the artillery, without

any infantry cover, but this was ignored by Jumel. With their flank turned the

French army was in disorder. it is said that at this moment Jumel yelled "lari!

lari!", intending to order a counterattack. These Malay words however

have the meaning of "Get out of here!" True or not, the complete French

army took flight, leaving behind an enormous amount of provisions and 280 (!)

guns. The French were hotly pursued by a squadron of dragoons, who made many

prisoners and badly wounded the able French chief of staff, Colonel Alberti.

The French were pursued all the way to the entrenched camp at Meester Cornelis.

The British took 6,000 prisoners, loosing only 520 killed and wounded, and the

victory enabled them to leave the unhealthy and marshy region around Batavia,

and to advance to the more healthy highland. They had now reached the

entrenched camp at Meester Cornelis, but it was clear to Auchmuty that he

needed heavy guns to bombard the French positions before he could attack with a

real chance of success. Therefore, Auchmuty gave up his positions at Tjilintjing

and ordered the fleet to move to Batavia were his siege train was disembarked.

The Governor-General Lord Minto in the meanwhile again dispatched an envoy to

Janssens, again demanding the surrender of the Dutch East Indies. Again,

Janssens refused. In addition, Lord Minto proclaimed to all the Dutch present

on Java that the British had come to end French rule, and that he would take

the island under the protection of the British Crown.

Janssens

used the time the British left him to strengthen his defences. The surrounding

terrain was inundated and additional batteries were thrown up. He tried also to

hamper British activities as much as possible by firing at them whenever a

suitable target was presented. During the night from 20 to 21 August, the British

broke ground, and threw up their batteries north of the entrenched camp. During

the morning of the 22nd, the batteries were finished and sailors started

hauling up the guns to arm them, when their labour was disturbed by a sortie

from the French. The sortie was however badly prepared, with troops getting

lost following difficult tracks in the wrong direction, and completely failed.

During the next days, a heavy cannonade was maintained on both sides. The

British guns were outnumbered, but this was made good by their better trained

gunners. The bombardment of the French positions lasted until the 25th. On this

day the redoubts no. 1 and 2 north of the entrenched camp were so badly damaged

that General Auchmuty decided to order a general attack on the camp, starting

during the night. While making his plan of attack he was greatly assisted by

information he received from a deserted sergeant. This sergeant marked out a

road leading through covered terrain, right up to another redoubt, no. 3. This

redoubt was situated on the right bank of the Slokkan canal and defended an

intact bridge across it. The main column, consisting of the brigade forming the

advance guard, and one brigade of the main army, would advance along this road,

take redoubt no. 3, and attack the entrenched camp: the advance guard would

attack south in the direction of redoubt no. 4; the other brigade west in the

direction of redoubt no. 2. To keep the French in the centre busy, another

column would make a feint attack from the north, to let the French believe that

the main attack would come from this direction. A third small column would take

redoubt no. 1. Finally, a fourth column would make a flank movement, by

advancing west of the Tjiliwong river as far as Campong Malaya, and then attack

the French from this direction. The attack of the first three columns would

take place at 3 o'clock in the morning of the 26th, while the flanking column

would leave around midnight.

The British

attack came not as a surprise for Lieutenant-General Janssens; he was informed

about the upcoming attack by a Scottish deserter. Therefore, he had given

orders to prevent a surprise attack. In addition, général de brigade

Jumel was ordered to take care that at 3 o'clock in the morning, all troops

would be in position. Around this time Janssens himself appeared at the

northern defences, asking Jumel if his orders of the previous day were carried

out. It became soon clear that they were not! Janssens harsh words to Jumel

were drowned in the noise of muskets fired and the shouts of the advancing

British. Led by the deserted sergeant the British advance guard arrived before

redoubt no. 3 unnoticed. The outposts were run over, and the gunners managed to

fire only one shot before the British were amongst them, who captured the

redoubt and the bridge behind it. Alarmed by the shots the French ran to their

positions in great confusion, but before they had time too react the British

advance guard also captured redoubt no. 4 at bayonet point. The British brigade

following the advance guard directed its attack on redoubt no. 2. But by now

the French were in position, and while they were climbing the walls they were

met by a withering fire. In spite of this they managed to enter the redoubt,

fighting hand-to-hand with the defenders. At this moment the following event

occurred. The Dutch Major of the artillery F.X. Muller and Captain Osman were

determined not to give up the redoubt entrusted to them without the utmost

resistance. So when it was clear the redoubt could not be held they threw a

fuse in the powder magazine. With an enormous explosion the whole redoubt blew

up, with friend and foe alike. The British were stunned and confused, and their

advance halted for a while. Now the time was there for the French to

counterattack, but their troops were not ready for this, unprepared as they

were for the attack. The right moment passed and the British resumed their

advance, capturing also redoubt no. 1. The British advanced along the whole

line, driving before them the defenders. When they reached the park, général

de brigade Jumel order all available cavalry to counterattack, in a last

effort to stop the British advance and to give the French time to rally.

However, at the same time he ordered the infantry to open fire. As a result,

the attacking cavalry was caught between two fires and repulsed by the British,

receiving heavy losses. Now all hope for Janssens was gone. During the battle

he tried several times, with danger to his own life, to restore order, but now

he had no other choice then to order the retreat. But at this moment the

British column that had outflanked the French positions appeared at Kampong

Malaya, and only a single file was open for the French to retreat. The

retreating French infantry was forced off the road by the remaining horse

artillery who moved at the gallop, followed by troops of wild buffalo's,

draught-animals of the train. The refugees were driven back by the British

infantry, right in front of the now attacking dragoons. These rode on much

bigger horses then the natives were used to, and these threw away their arms

and surrendered en masse. The British made six thousand prisoners, including

two hundred officers. Their pursuit ended at Tjanjong-Oost, about ten

kilometres south of Meester Cornelis. They took the greatest care for the

wounded of both sides. A number of 'gentlemen', on their way from Batavia in

their carriages to sight-see the battlefield, were ordered to hand over their

carriages to transport the wounded, much to their chagrin!

Lieutenant-General

Janssens was one of the last to leave the battlefield. Nearly captured, and

after a difficult journey, he reached Buitenzorg were he met part of his staff

and the few remains of his army. Also there was an envoy from Lord Minto, to

demand for the third time his capitulation. Janssens' answer was 'that the

British had captured no more then a tenth of the island Java, and that he would

not capitulate before he had not one soldier left to resist! War has its luck,

and until now it was not at the side of the French. But this will change and

will decide the final outcome.' Janssens ordered Colonel Motman to rally the

troops and to send them to Samarang under the orders of reliable officers. In

addition, he summoned all native sovereigns to fulfil the obligations they were

bound to by treaty, and to send their contingents of auxiliaries also to

Samarang. Discipline however was bad among his native soldiers; most of them

had enough and deserted in droves, murdering the officers trying to stop them.

But instead of leaving for home they followed the retreating French column,

killing stragglers and firing their muskets at them -if they still had them.

The time come for them to take revenge. Finally, the retreating army was down

to about forty European infantry, a hundred dragoons and the remaining

officers. On the 29th they were attacked by about five hundred native

deserters, but these were repulsed by especially the officers, which had armed

themselves with muskets.

Lieutenant-General

Janssens refused to see général de brigade Jumel, whom he held

responsible for the disaster. Jumel accompanied the retreating column for a few

days but no-one followed his orders anymore. Therefore he decided to leave by

carriage and to go to Cheribon, to prepare the fortress there for defence.

Cheribon was strategically very important, as it controlled communications

between the eastern and western part of Java. However, General Auchmuty knew

this also, and had dispatched an infantry battalion embarked on some frigates

to capture the place. Arriving in front of the city, it was occupied without

resistance after Lieutenant van der Werf, who was in command at the fortress,

had taken a commission in the British army! So when Jumel arrived he was

immediately taken prisoner. Another part of the British army was send to Karang

Sambong, to prevent a retreat of the defeated French army to the west. They

managed to cut of a column retreating in that direction. Outnumbered and

without artillery and nowhere else to go the troops surrendered. As a result,

all French resistance west of Cheribon ceased. However, Auchmuty was in the

dark about the plans and location of Janssens. He thought that Janssens was at

Soerabaya, more specific at the fortress 'Lodewijk', to defend this region.

Therefore on 5 September he embarked part of his army, to land at Sadajo, near

this fortress. However, when he had reached Cheribon, he learned from a

captured letter that Janssens was at Samarang, not at Soerabaya. Accordingly,

Auchmuty changed his plans and decided to land there, to repulse Janssens to

Soerakarta and then to undertake the occupation of eastern Java. Arriving

before Samarang on the 9th, again an envoy was send to Janssens, who again

refused to surrender.

When

Lieutenant-General Janssens arrived at Samarang, he really found that a number

of native sovereigns had fulfilled their obligations and had send their

contingents of auxiliaries. However the contingent of the Sultan of Madoera

almost immediately had to return, because the island was threatened by the British

fleet. Their remained about 6,000 men, consisting of the contingents of the

Emperor of Soerakarta, the Sultan of Djoejokarta and the Prince Prang Wedono.

Quality of these auxiliaries was bad; their armament consisted mainly of pikes

and sticks, morale and discipline were bad. With the garrison battalions of

Samarang and Soerabaya added, Janssens had about 8,000 men at his disposal. It

was clear to him that he would stand no chance in defending Samarang, which was

without defences and could be bombarded by the British fleet. Therefore he took

up a strong position at Oengaran, waiting for the arrival of Auchmuty. His

position was on a series of heights with steep slopes, both wings resting on

impassable terrain. Turning the position was only possible by a very long

detour, through very heavy terrain. When General Auchmuty, in the morning of

the 12th, noticed that Janssens had evacuated Samarang and removed the guns of

the coastal defences, he immediately started landing his troops, which lasted

until the morning of the 13th. He met however a serious setback, because

Vice-Admiral Stopford had sailed further east with the fleet and most of the

transports, in order to capture the 'Lodewijk' fortress and Soerabaya, which

had safe roads for his fleet during the upcoming monsoon. Therefore, General

Auchmuty was left with 1,200 men and six field guns only. Nevertheless he

decided to attack immediately, while the enemy was still demoralised and his

weakness unknown to them. Taking in regard the position taken up by Janssens

and thrusting the quality of his soldiers he decided on a frontal attack, led

by Colonel Gibbs. This decision proved to be right. Janssens' troops were

completely taken by surprise and the undisciplined auxiliary troops, already

weakened by mass desertions, took flight, killing the European officers who

tried to stop them. Victory was complete. With only slight losses the British

had taken an enormously strong position. This proved to be decisive, Janssens

army was completely defeated. Accompanied only by a few officers Janssens

retreated to the Salitaga fortress. During the night he despatched a request to

General Auchmuty for a cease-fire, in order to open negotiations with Lord

Minto in Batavia. Auchmuty refused, not wanting to loose any more time, and

declared that negotiations had to take place with himself. On 18 September at

Toentang Janssens capitulated, the remains of the French army lying down their

arms before Auchmuty. According to Wüppermann this was not very difficult; only

one musket was left! All French forces on Java became prisoner of war. On 18

October 1811 Janssens sailed from Batavia to England as a prisoner of war.

During his imprisonment, on 22 February 1812 Janssens received the Great cross

of the Order of the Reunion.

The Final years,

1812 – 1838

After giving

his word of honour not to fight against the British and their allies until

exchanged properly the British brought Janssens back to France, putting him

ashore at Morlaix on 11 November 1812. On 15 January 1813 he was appointed

Commander of the 31st Military Division at Groningen, in the former Kingdom of

Holland. Two months later, on 5 march 1813, he was ordered to go to Coevorden,

situated on the southern border of his Military Division, to prepare this

fortress for defence. On 24 March he was appointed Commander of the 2nd

Military Division at Mézières. On 30 March Janssens was exchanged properly, but

for the time being stayed as Commander at Mézières. On 5 March 1814 he received

orders from Napoleon to collect all available troops of the Ardennes fortresses

to attack Blücher's rear at Laon, and then to join the army in Champagne. On 14

March he reached the army near Reims with 3,000 men, and two days later was

incorporated with the troops commanded by Marshall Ney. During the battle of

Arcis-sur-Aube on 20 March Janssens was wounded, and received permission to

leave the army and to go to Paris, to be employed again by the Minister of War.

However, on 9 April Janssens asked and received his dismissal from the French

Army.

Leaving

France for the Netherlands, on 9 May 1814 Janssens joined the Netherlands army

in the rank of Lieutenant-General, the same rank he held in the French army,

and was by William of Orange charged with the direction of personnel with the

Department of War. This gave him a lot of trouble. Many officers tried to

obtain a position in the new Netherlands army. Aged Orangist officers who saw

no service since 1795, former Batavian and former French officers, and officers

and civilians which only experience was their conduct during 1813, in the

'liberation war' of the Netherlands. In addition, Janssens was asked to 'lobby'

with William of Orange by a number of officers that had fought with distinction

in the French army under Napoleon, to receive a place in the Netherlands army.

Among these were the Generals Daendels and Dumonceau. Not surprisingly, in

these cases, Janssens did nothing, in order not to compromise himself, and also

to keep all able possible rivals far away from his own position. As a result,

his relations with many officers was worsening, making his position even more

troublesome. Furthermore, bringing the Netherlands army on full strength was a

problem. On 3 July 1814, of the 53,607 men that were needed to bring the army

at full strength, only 34,097 were present. And of these many had to send away

because they were unfit for duty. But that is another story…

On 8 July,

Janssens was also appointed President of the Commission for the Organisation of

the Colonial Army. On the 24th of the same month, Janssens became President of

the Commission for the Organisation of the Netherlands Army. Already four days

later, on the 28th, he became provisional Commissary-General of War. For the

third time, Janssens was ordered to create an army! On 31 August, he was appointed

Commissary-General of War of the Southern Provinces. However, Janssens had

other plans for himself. A new Governor-General for the Dutch East Indies was

needed, and Janssens was highly interested in this profitable position.

However, the loss of Java during his leadership and the problems he had in the

relations with the natives were the cause that he was not chosen for this

important position 8). Angered by this, on 19 September Janssens asked for his

dismissal, which was ignored by William of Orange. Asking for his dismissal

again on 8 December, it was again refused; the young Kingdom could not do

without his experience right now. On 11 December this function was combined

with that for the Netherlands, and Janssens was offered to become Commissary-General

of the United Departments of War, with the rank of Secretary of State.

Beginning in this quality on 1 January 1815, Janssens finally received his

resignation on 22 May 1815, ending his active duty at the age of 52.

Two days

later, on 24 May 1815, Janssens was appointed President of the Commission for

the Design of the Regulations of Administration and Discipline for the Militaire

Willemsorde ('Military Order of William'). On 8 July he was distinguished

by being made a knight of the Grootkruis of the Militaire Willemsorde,

and appointed Chancellor of the Order. On 7 November 1816 he was authorized to

wear his decoration of grand officier de la Légion d'honneur, to be

confirmed by the King of France on 6 October 1817. Finally, Janssens became

also a member of the Netherlands nobility when he was made a Jonkheer by Royal

Order of 24 November 1816. On 10 November 1828 he was also promoted to General

of Infantry, the highest rank existing in the Netherlands army. On 9 January

1834 Janssens was charged with the function of Chancellor of the Orde van de

Nederlandse Leeuw ('Order of the Netherlands Lion'). This would be his last

appointment; he died on 23 May 1838 in The Hague, 75 years old.

Assessment

Jan Willem Janssens was a soldier his whole life. Although brave, his qualities

on the battlefield were mediocre. Doing his best on Java he was not able to

withstand the British invasion with the troops he had at his disposal. A job I

think Daendels would have done much better. Since Janssens relieved Daendels as

Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies, relations with him were -not

surprisingly- very bad. Janssens however served much better in administrative

duties This was duly recognised by Louis Bonaparte -who also needed all the

Dutch support he could get- and later also by William of Orange. William gave

him the task to create the Netherlands army, something even more difficult to

accomplish because of the incorporation of the 'Belgians' and the problems

already described. That Janssens succeeded in creating a useful military force

out of the scarce resources, with so many men trying to obtain the best for

themselves, with or without the right capabilities, became clear during the Waterloo

Campaign. During this campaign, and looking at the circumstances, the green

Netherlands army gave a very good account of themselves. It was characteristic

however that Janssens held no field command during this campaign, and already

in May received his dismissal. Rather strange, one of the most experienced

Dutch officers was not present with the army during the most critical moment of

the existence of the Netherlands nation.

Bibliography

-

Aa, A.J. van der, Biographisch Woordenboek der Nederlanden (Haarlem

1855)

- Bas, F. de, Prins Frederik der Nederlanden en zijn tijd (Schiedam

1887-1913)

- Colenbrander, Dr. H.T., Gedenkstukken der Algemeene Geschiedenis van

Nederland van 1795 tot 1840, Part 7; Vestiging van het Koninkrijk 1813-1815

('s-Gravenhage 1914)

- Dronkers, Mr.J.M.G.A., De Generaals van het Koninkrijk Holland, 1806-1810

('s Gravenhage 1968)

- Six, Georges, Dictionnaire Biographique des Généraux & Amiraux

Français de la Révolution et de l'Empire (1792-1814) Tome I (Paris 1934 /

1974)

- Wüppermann, Generaal, Nederland voor Honderd Jaren, 1795-1813

(Amsterdam / Utrecht 1813)

© Geert van Uythoven

Footnotes:

1) In

French, his first names are 'Jean-Guillaume'.

2) For

details on the 1787 campaign, see my articles "The Prussian Campaign in

Holland 1787", part I - IV, which appeared in the magazine First Empire,

issue No. 44 - 47 (1999).

3) One of

the conditions stipulated in the treaty of The Hague (16 May 1795) was, that an

army of 25,000 French would remain in the Batavian Republic to protect it

against the 'aggression of the Allies and to guarantee its independence'. This

army would have to be fed, clothed and paid by the Batavians. The French

developed a special system for the 25,000 troops the Batavian Republic had to

feed, clothe and pay. Ragged troops from the front line armies were send to the

Batavian Republic, were they were fed, paid, and clothed again. After some

time, the troops moved to the front, fully equipped and rested, and a new

ragged and hungry contingent arrived. This situation stimulated the hatred

against the French.

4) Order of battle of the forces at the disposal

of General Janssens.

5) The

latter appointment was seven days later changed in Privy Council in normal

service.

6) This

Order was on 14 February 1807 changed in the Koninklijke Orde van Holland

('Royal Order of Holland'), and again changed on 23 November in the Koninklijke

Orde der Unie ('Royal Order of the Union').

7) Although

the army was formed of Dutch and Malayans, I will call it 'French' because from

1810 until 1813, as already told, the Netherlands were part of the French

Empire.

8) Not

surprisingly, General Daendels was one of those who advised strongly against Janssens

as being appointed Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies.